The Rules They Are A-Changin’

This article was written by Cecilia Tan

This article was published in The National Pastime: The Future According to Baseball (2021)

Before we can talk about the future of the rules in baseball, we ought to have a peek at the past. But more importantly we should acknowledge that the reason we’re so interested in the future of the rules right now is because in 2021 anxiety over Major League Baseball’s rules is running high. The owners and Commissioner Rob Manfred believe the long term health of the game is in jeopardy from loss of fans, and the commissioner is trying to address that loss through rules changes, imposed unilaterally if necessary.1 On the part of the fans, the anxiety stems from change itself. (Indeed, it follows that die-hard fans of a sport that so highly touts its traditions would be traditionalists.)

Nonetheless, major rules changes have been implemented successfully at the major-league level before without the sky falling. Some of the seemingly most drastic have come within living memory for many fans. The mound was lowered and the strike zone shrunk significantly after the pitching domination of 1968.2 The designated hitter was finally adopted in the American League (after having been debated since the nineteenth century3) in 1973.4 Video replay review was first introduced in 2008 in a limited way, then expanded in 2014.5 But the pace of change has accelerated in the Manfred Era, leading Manfred himself to say of purists who have decried the rules changes under his watch, “Their logic, I believe, is: ‘He wants to change it, therefore he doesn’t love it.’ My logic is: ‘I love it, it needs to be consummate with today’s society in order for people to continue to love it, and therefore, I’m willing to take whatever criticism comes along in an effort to make sure the game is something Americans will continue to embrace.’”6

THE MANFRED ERA

Before Rob Manfred became commissioner in 2015, he had been working in and around Major League Baseball since 1987, including representing the owners as outside counsel in the 1994-95 labor negotiations.7 For purposes of this article, though, we’ll consider the Manfred Era as beginning on September 28, 2013, when he was named Chief Operating Officer of MLB by then-commissioner Allan “Bud” Selig, a move that cemented Manfred’s role as Selig’s heir apparent. Baseball being criticized for being “slow” is nothing new.8 But under Manfred, MLB began to beat the drum that something had to be done about the slow pace of play, lack of game action/balls in play, and over-three-hour game times, because the league was losing fans.9 Some rules tinkering got underway by 2014, when a 20-second pitch clock was imposed in the Arizona Fall League, and by 2015 had spread to the Double and Triple A levels of the minor leagues.10 In February 2015, Manfred had been in the commissioner’s chair for less than a month when MLB announced new rules intended to speed things up.11 These included a clock on the inning breaks, the ability of managers to call for a replay challenge from the dugout instead of having to come on the field, and a mandate to enforce Rule 6.02(d) which requires hitters to keep one foot in the batters box during an at-bat.

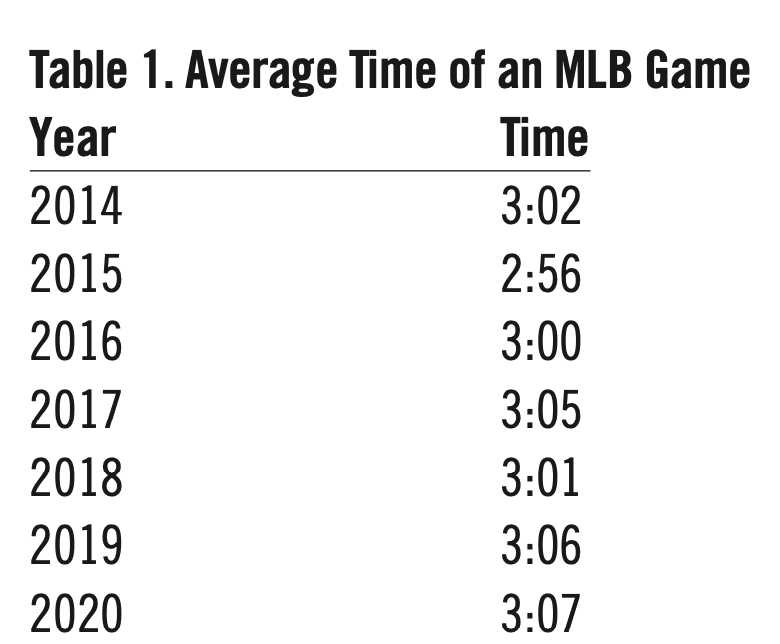

Batters were not thrilled about the sudden enforcement of a rule that they had been flouting at will for decades.12 Umpires didn’t seem particularly invested in enforcing the rule, either, and although the average time of game dropped by six minutes from 2014 to early 2015, the time began to creep right back up, lengthening from around 2:53 at the start of the season to 2:56 by the end.13 By 2016, games averaged three hours again. (See Table 1.) In 2017, the intentional walk rule was changed to allow managers to simply tell the umpire to give first base to the hitter, eliminating the need to pitch the four largely ceremonial balls to the catcher. No one expected that to save a lot of time, and it didn’t: the average time of game rose again to 3:05, so even more changes were introduced before the 2018 season, including a limit of six mound visits per nine-inning game, new time limits on inning breaks, and putting time clocks on pitching changes.

Table 1. Average Time of an MLB Game

Sources: AP, CBS Sports14

In 2019 mound visits were trimmed from six to five, and new inning break limits were introduced, with local games’ break time reduced from 2:05 to 2:00, and national games from 2:25 to 2:00 — eliminating an entire advertising slot! — and the commissioner’s office warning that for the 2020 season they “retained the right” to reduce the inning breaks to 1:55 in both local and national games.15 By far the most contentious of the changes, though, was the rule requiring relief pitchers to face a minimum of three batters, which many argued would have the opposite from the intended effect. Cliff Corcoran of The Athletic wrote that “the three-batter minimum is rife with irony — a rule intended to make games shorter will likely make them longer; a rule intended to save fans from enduring mid-inning pitching changes will only make them more desperate to see them.”16

Of course in 2020 the novel coronavirus pandemic forced MLB to renegotiate the entire existence of the season with the MLBPA, including new rules governing travel, health, and safety, as well as “emergency” rules that had on-field effects such as the universal DH in both leagues, seven-inning doubleheaders, and an extra innings rule that placed a runner at second base to start each half-inning. Somehow in 2021, seven-inning doubleheaders and the extra innings rule have remained, despite the easing of the pandemic and the derisive clap-chants from the Yankee Stadium bleachers to “Play-Real Base-Ball!” every time the extra runner on second appears.

A much bigger rule “change” in 2021, though, is MLB’s crackdown on “sticky substances.”17 Although it has been illegal to “doctor” the ball with Vaseline or any other substance since the last legal practitioner of the spitball, Burleigh Grimes, retired from the game in 1934, for years it has been an “open secret” that a majority of pitchers used some kind of substance (other than the approved rosin) at least some of the time to improve their grip. With the crackdown ongoing as this paper is being written, it remains to be seen just what rules changes might come out of it. Some have suggested that a substance be made legal for pitcher use similar to rosin. Others have suggested that all pitchers and their gloves, hats, and uniforms be inspected before every inning. History suggests that the sticky substance crackdown is akin to the steroid crackdown: a problem that was allowed to grow unchecked for more than a decade before MLB decided it had to step in. Where the sticky substance debate seems to differ is that fans seem to be less angry over sticky stuff than they were about steroids, as if cheating with performance-enhancing goop is somehow less egregious than performance-enhancing drugs.

Is part of the muted reaction to “sticky stuff” on the part of fans — especially when compared to steroids, or even the Astros recent trash-can banging cheating scandal — because fans accept “sticky stuff” as part of baseball’s status quo? When trying to project what baseball’s rules will look like in 2040, it’s one of the questions we must ask. But sometimes it’s tricky to determine what “feels like baseball” and what doesn’t.

That’s where play-testing comes in.

THE ATLANTIC LEAGUE EXPERIMENT(S)

Many of the rules changes that have been considered and/or implemented by MLB under Rob Manfred were not cooked up in the comissioner’s office; they’ve already been used somewhere. For example, the Southeastern Conference (SEC) has been using a pitch clock in college baseball since 2010.18 And then there’s the Atlantic League. This unaffiliated independent baseball league was already trying some rules innovations on their own before MLB made them an official testbed.

At the time when Rick White became president of the Atlantic League, MLB had just started investigating pace of play. In 2014, MLB created a blue ribbon Pace of Game committee.19 That same year, the Atlantic League just went ahead and began enforcing both Rule 6.02 (batters cannot step out of the box) and Rule 8.04 (pitchers have 12 seconds to deliver the ball after receiving it), limited teams to three 45-second “time outs” per game — including mound visits, reduced warmup pitches from eight to six, and started calling the rule-book strike zone (including the high strike). Reportedly, time of game immediately dropped by eight minutes.20

“We took it upon ourselves to take an initiative to reduce the time of play and the pace with which the game was played,” White said when asked. “And we openly shared our data with MLB. They never asked for it; we just did it.”21 The relationship between the Atlantic League and MLB developed over time. White and Manfred had known each other from the era when White had founded Major League Baseball Properties and Manfred had been working on MLB labor issues. When White and a group of Atlantic League owners met with then-COO Manfred in 2014, their main hope was to reach an agreement governing the transfer of players from their league to MLB. “We anticipated he was going to become the commissioner,” White explained. “We wanted to introduce the league to him, and I don’t think that he had a real conscious thought about who we were and who composed our league, especially on the playing side. But in that meeting, we talked about the quality of play in our league and we threw out — you know, as an opportunity — the idea for us to beta test initiatives. We really didn’t think that was going to go anywhere.”

But Manfred saw in the Atlantic League an ideal place to experiment with rules changes. The Atlantic League is a better test environment than the affiliated minor leagues because of its nature as a “second-chance league.” The Atlantic League is populated with experienced players — 80% with major league or Triple AAA experience, according to White — and its teams are not controlled by major league clubs. This means the competition is more analogous to major-league play than one finds on a Double A team being forced to play the 0-for-35 prospect whose multimillion dollar signing bonus needs to be justified, or the pitcher on the trading block. Because the minor league franchises must cater to the needs of their major league club, it “creates a bit of an artificial dynamic for what MLB’s trying to accomplish.”22

To increase the ability to make meaningful comparisons, the changes have mostly been A/B tested by splitting the season into two halves-one half with a rule change, one half without. In addition to the pace-of-play changes implemented in 2014, the Atlantic League has been experimenting over the past few years with ways to increase the amount of action in a game. Changes designed to boost baserunning have included banning the usual lefty pickoff move (pitcher must step off the rubber before making a move), limiting the number of pickoffs per at bat to two, increasing the width of the bases to 18 inches, and introducing the “steal of first base” — allowing a batter to run to first on any dropped strike, not just the third strike. The step-off-before-pickoff rule in particular “has led to Atlantic League games turning into track meets of sorts,” according to Baseball America’s J.J. Cooper. “Since the rule was put into place, stolen bases have nearly doubled from 0.7 steals per team per game to 1.3.”23

Defensive shifts work well — too well — so to encourage more success on balls in play, the Atlantic League has experimented with a rule that all infielders must be on the infield dirt when the ball is pitched. One rule tested to help batters at the plate looks small — you get two shots to bunt foul on the third strike instead of one — but one slated to be introduced in the latter half of 2021 looks huge: moving the pitching rubber back by a foot.

Originally the plan to move the rubber had been slated for the second half of 2019 and the move was slated to be two feet — to 62′ 6″ — but the plan was later scrapped. Instead, in 2021, the Atlantic League will try a 61′ 6″ distance. Some pitchers expressed worries the increase could lead to injuries.24 But recent studies suggest that altering the distance between the mound and the plate doesn’t change a pitcher’s mechanics and won’t lead to additional injury.25 The change of one foot of distance is expected to be the equivalent of reducing pitch speed by 1.5 mph. Is one foot enough to make a difference? “If you look at the majority of hitters today, because they are trying to get an instant more time to see a pitched baseball, they methodically stand at the very back of the box,” says White. “And if you really pay attention early in the game, most hitters at the big league level go in and start erasing the back line of the batters box.”26 With pitchers throwing 100 miles per hour with regularity now, hitters will take every inch they can get.

The Atlantic League has also experimented with a “consistent grip” baseball that “is tackier than the model used in both affiliated baseball and the Atlantic League,” and would negate the need for pitchers to use something sticky merely to improve grip and control because the ball has already been pre-treated to be tacky.27 The consistent-grip ball is also brighter white, and potentially easier to see, since it doesn’t have to be rubbed with mud before each game the way the MLB ball is. (MLB has also experimented with the “consistent grip” baseball in the Arizona Fall League, but has been largely silent on the subject throughout the recent announcements about the sticky substance crackdown.)

But we haven’t even talked yet about the Atlantic League experiment that seems the most futuristic, the so-called “robo umps.” Automated Ball-Strike (ABS) uses the TrackMan radar system (the same system MLB used for PitchF/X before it was superseded by Hawk-Eye/Statcast) to judge balls and strikes and then relay the call to the home plate umpire via an earbud. To fans in the stands, ABS “runs so smoothly that most fans don’t even know the home plate umpire isn’t in charge of determining the strike zone.”28 To get into the nitty gritty of what using ABS is like, I spoke to the umpire whose earbud was sent to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum after being the first to use the system in a game, Fred DeJesus.

“It’s a blessing in my eyes,” DeJesus said. “[With ABS] you don’t have those Billy Martin/Earl Weaver style arguments anymore.”29 DeJesus was an umpire in the affiliated minor leagues for years before taking the gig with the Atlantic League (as well as a day job in public education). In DeJesus’s view, ABS lets the home plate umpire concentrate on other aspects of the game — which, by the way, include maintaining the pace of play. “ABS helps all of us with slowing our timing down, being more patient, and letting the game come to us,” he says. When asked whether a rules change can make the game more exciting, though, DeJesus is pragmatic: “It’s players that make the game exciting, not the rules.”30

Beta-testing systems like ABS and rules changes in the Atlantic League ultimately gives MLB what Rick White calls a “safety valve. They don’t want to change their on-field product until they’ve fully parsed the results.” MLB naturally wants to see if there are unintended consequences or bugs in the systems. Players don’t always react to a rule as intended, as shown in MLB when attempted enforcement of rule 8.04 in 2009 merely led to pitchers shrugging and paying fines rather than speeding up their game.31

Among the lessons learned so far from the Atlantic League experiments is the realization that ABS was calling the high strike more than expected not just because the rulebook strike zone is higher than the one typically used in practice in MLB — but because it calculated the height based on each player’s reported height. This meant that any player who had overstated his height (a common, if questionable, practice32) was penalized with a strike zone intended for a larger person. For the 2021 season, the ABS system is being tweaked to call a lower — and wider — strike zone, one that more closely resembles what major-league umpires call.33

Hawk-Eye high speed cameras overlooking an athletic event in 2020 (HAWK-EYE INNOVATIONS)

The other big takeaway was that ABS revealed that everyone — catchers, hitters, umpires — reacts in-game as if the strike zone is a two-dimensional window at the front of the plate rather than the as-defined prism of three-dimensional space above home plate. No one I spoke to was sure why, but one guess is that this could be a consequence of what is now two decades of television “K-Zone”-style projections being subconsciously absorbed.34 In theory, the strike zone is a column of air; in practice, it is a window, and to reflect that, the ABS system has been adjusted in 2021 to measure it like one. We’ll see what effects that has ingame as the season goes along. Meanwhile, MLB has imported several successful experiments from the Atlantic League into one or more of its own affiliated minor leagues for the 2021 season:

- Triple A: 18-inch-square bases with a less-slippery surface

- Double A: Infielders must be on the infield dirt when the pitch is delivered

- High-A: Pitchers must step off the rubber to attempt a pickoff

- Low-A: A limit of two pickoff attempts per plate appearance

- Low-A (West): A 15-second pitch clock

- Low-A (Southeast): Automatic Ball-Strike system

THE FUTURE OF THE RULES

My first prediction is an easy one: Given the nearseamless success of ABS in the Atlantic League, it seems assured that in the short term — within five years — we will see some form of ABS adopted for use in Major League Baseball. In the bigs, it will likely utilize Hawk-Eye, which MLB claims is accurate down to 1/100th of an inch.35 Although attendance figures are often quoted as the reason for taking action, there is little doubt that one of MLB’s aims is to make the game more appealing, exciting, and engaging for the broadcast audience.36 As such, it no longer makes any sense to have the viewers at home (or anyone in the stadium with the MLB At Bat App) better informed about the positions of balls and strikes than the home plate umpire. Umpires should be demanding this tool be put at their disposal as soon as possible so they can stop looking like fools every night on television. To make a small prediction based on previous reactions to change: MLB umpires won’t do anything of the sort until it is imposed on them by the commissioner’s office.

Future iterations of ABS could calculate the strike zone in real time based on the hitter’s stance. Could we see some hitters adopting a boxer’s crouch to reduce the target area? The big leagues changed the strike zone after the 1968 season to create a more hitter-friendly environment. With an ABS system, MLB could easily tweak the size and shape of the zone on a yearly basis, tipping the balance of power in either the pitcher’s or hitter’s favor, depending on which seemed to be gaining the upper hand.

Assuming ABS is a given, I asked DeJesus what’s the one call he wishes umpires had technological help to make? “Checked swings,” he said, without hesitation. Fred, I have good news: in the future, that’ll be doable. By 2040, the cutting edge of technology won’t merely be better cameras for Hawk-Eye or its successor, but more sophisticated software and data processing on what those cameras capture. These advances will allow “robo umps” to judge more than just the strike zone. Engineers at MLBAM are already working on using Hawk-Eye data to track not only the position of each player on the field, but biometric telemetry of their bodies’ posture and joints.37 Soon, processing the data will not only be able to recreate a VR simulation of actual play for entertainment purposes, it will be able to make safe/out calls that the human eye cannot: for example, plays that were obscured by a player’s body.

You might think that my next prediction would be that by 2040 we won’t have human umpires at all, but you’d be wrong. I don’t believe it will be desirable to replace a human umpire entirely, and that technology should continue to be framed as a necessary tool to help umpires perform their jobs at the highest level. It is necessary to keep the umpires at least as well informed as the viewing public, and makes no sense to have the audience in the twenty-first century and umpires in the nineteenth. The earbud of 2021 could take the form of a wearable for umpires by 2040, maybe something akin to Google Glass (or a contact lens) with a visual heads-up display. Perhaps there will be an eye-in-the-sky — which could be an umpire in the press box, or in Secaucus like MLB’s current video review crew — with access to all the tracking data, who automatically buzzes the on-field umps when their calls need to be amended.38 In that vein, expect the current use of video replay — where each manager needs to issue a challenge to a call on the field — to be long gone by 2040. If MLB’s goal is a faster-paced, more streamlined game, the manager challenge bringing the game to a halt needs to go. Incorporate technological feedback into all aspects of umpiring, and it will not only be seamless, the end result on the field will be a game that looks and feels more like “traditional” baseball than the manager challenge does.

By 2040, expect the baseball itself to have changed, as well as the rules governing the ball’s specs. Another hallmark of the Manfred Era is MLB tinkering with the ball. Rawlings has been the official manufacturer of the baseballs used in the major leagues for over forty years. After the 2017 surge in both home runs and pitcher blisters may have been caused by a small change in ball manufacturing, MLB bought Rawlings in 2018 to solidify control over that process.39 Prior to the 2021 season, MLB announced it had deliberately made changes to the ball intended to suppress the home run surge.40 Whether the change worked as intended — and it doesn’t appear that it did41 — the new status quo appears to be MLB deliberately experimenting with the ball itself. Making the ball lighter, heavier, with denser or lighter wool, with seams higher or lower, perhaps with a “consistent grip” covering as previously mentioned, each will affect the ball’s drag and Coefficient of Restitution (bounciness). With the same technology that is allowing pitchers to unlock the mechanics behind Seam-Shifted Wake, expect MLB to eventually master what each potential change to the ball itself will do.

The Atlantic League experiments presage that the distance from the plate to the pitching rubber will be increased in the future. But are we going to see field dimensions overall increase? The height of the average American has been growing for over 100 years. Why shouldn’t the field dimensions adjust to reflect that? In 1918, the average American army soldier was 5-foot-6 (while Babe Ruth was 6-foot-2).42 Nowadays, the average MLB hitter is over six feet tall, and pitchers are taller still. Increased player size alone accounted for an 11 percent jump in the annual home run rate from 1946 to 2005.43 People and players continue to get bigger, and at the major league level they tend to be the biggest. We already have the concept that field size should be appropriate to player size: the Little League field has 60-foot basepaths and a 45-foot pitching distance, while Pony League (age 13-14) has 80-foot basepaths and a 54-foot pitching distance. The main reason I don’t believe we’ll see 100-foot basepaths and 450-foot outfield fences in MLB by 2040 is that it would be too expensive to retool stadiums to change the field size that drastically, plus there’s the fact that if MLB is seeking a boost in baserunning and steals, increasing the distance between bases will hurt. (In fact, with the likelihood that larger bases will be adopted, the actual basepath will technically shrink by a few inches.) Rebuilding the entire field in major league ballparks isn’t economically feasible, but moving the mound is.

When it comes to MLB in 2040, though, nearly everyone I mentioned my predictions to while writing this article wanted to know whether I thought there would eventually be a universal DH or if the DH would eventually be phased back out of the major leagues. If I am going to be logical about my predictions, I’m going to say that the players union will eventually get the DH approved in the National League. Of course, there’s the possibility that the DH may take some other form, like the double hook rule being tested in — you guessed it — the Atlantic League in 2021. The double hook rule is intended to influence teams away from openers and extreme bullpenning because you lose the DH when you pull your starting pitcher from the game. My prediction if the double hook rule were to become standard in MLB is that the players union would only support it if it were accompanied by expanded active rosters. For those who are anti-DH, would that be better or worse than what we have now? The DH or no-DH question seems to inspire intense feelings in baseball fans. Trying to answer the question leads to existential questions about baseball itself.

WHAT IS BASEBALL, ANYWAY?

Perhaps it boils down to aesthetics. MLB would like the game to evolve in a direction that is more exciting, engaging, and appealing than the game as it is played today. (This is why I haven’t predicted any rules against bat flips or home plate celebrations.) But batting average in 2021 is on pace to be as low as in 1968.44 And balls in play are on pace to be even lower, having dropped from 133,000 balls in play in 2007 to 119,000 in 2019 and still decreasing.45 MLB firmly believes that a game dominated by the “three true outcomes” is not the most engaging version of baseball. They believe more balls in play and traffic on the bases will equate to more excitement and more fans. A noble aim, but… would that mean we need more DHs or fewer?

It seems to me that if something looks and feels like “baseball” to die-hard fans, they’ll accept it. If it feels like a gimmick or just plain weird — like the extra-innings tiebreaker rule feels to the Bleacher Creatures — then it’s not “real baseball.” And the danger is that if we have too many rules changes — or even one deal-breaker — such that the game no longer feels like the sport we love, that would drive fans away, too. What will fan reaction be to the Pioneer League’s tiebreaker plan for the 2021 season: a home run derby?46

Perhaps the five-pitch swingoff will fly in the Pioneer League because the minor leagues have greater license to be unorthodox in the name of entertainment, whereas what the major leagues do, by definition, is the orthodoxy of the game. This is why to this day some opponents of the DH call it an abomination.47 The way I see it, the schism over the DH reveals two opposing aesthetics of baseball. In the version of baseball where the DH is prized, the central conflict at the heart of the game is the confrontation between the pitcher and the batter. Everything else — including fielding and baserunning — is secondary to that one-on-one confrontation. By contrast, the aesthetic of pre-DH baseball comes in its purest form from the nineteenth century days of nine-versus-nine, when the game was not so far removed from when the “pitcher” was there to serve the ball to the batter so that it could be put into play and result in lots of running around. Looked at that way, if there’s no one on base, it’s not base ball.

By 1891 we already had the schism forming, though, between those who believed the aesthetics of the game centered around the ball in play, and those who believed it centered around the batter-pitcher confrontation. In 1890, the nine-versus-nine folks compromised to allow two additional players on the roster for substitutions, but in 1891 they stopped short of the pitcher being declared a non-batter despite the already obvious fact that most good pitchers can’t hit.48 Here we are, 130 years later — with rosters having grown to 26 players, and pitchers even worse at hitting than ever before49 — still debating the same thing. The problem with aesthetic debates, of course, is that neither side can be proven right or wrong. Ultimately the “proof” will be measured by the number of fans in seats and eyeballs on screens. My prediction for 2040 is that baseball will retain its cultural relevance, no matter how much tinkering the powers that be may do.

CECILIA M. TAN was a professional science fiction writer and editor for two decades before she became SABR’s Publications Director in 2011. Her short stories have previously appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, Absolute Magnitude, Strange Horizons, and Ms. Magazine, among many other places. In addition to comma-jockeying for SABR, she has exhibited her baseball editing prowess for various sites and publications, including Baseball Prospectus, the Yankees Annual, and Baseball-Reference.com. This issue of The National Pastime has given her a rare chance to combine her favorite subjects.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Stew Thornley, J.J. Cooper, Rick White, and Fred DeJesus for speaking with me at length on this topic and to Cliff Blau for being the gold standard of fact-checking.

Notes

1. At Cactus League Media Day 2018, Manfred told the media, “Pace of game is a fan issue. Our research tells us that it’s a fan issue. Our broadcast partners tell us it’s a fan issue.” (MLB’s research on the subject has not been made public, however.) Richard Justice, “Manfred talks pace of play, rebuilding clubs,” MLB.com, February 20, 2018. https:// www.mlb.com/news/commissioner-rob-manfred-talks-pace-of-play-c26681889.0; Tom Verducci, “Rob Manfred’s stern message: MLB will modernize, no matter what players want,” Sports Illustrated, February 21, 2017. https:// www.si.com/mlb/2017/02/22/rob-manfred-mlb-rules-changes-mlbpa-tony-clark.

2. Michael St. Clair, “Four stats show why the mound was lowered in 1968,” MLB.com, December 3, 2015. https://www.mlb.com/cut4/why-was-the-mound-lowered-in-1968/c-158689966.

3. “Messrs. Temple and Spalding Agree That the Pitcher Should be Exempt From Batting,” Sporting Life, December 19, 1891, 1. See also John Cronin, “The History of the Designated Hitter Rule,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol 45, No. 2, Fall 2016, Society for American Baseball Research: 5-14.

4. If one needs more evidence of the traditionalist streak in baseball fandom, I’ll note that nearly fifty years of the designated hitter in the American League still hasn’t stopped a certain stripe of traditionalist from continuing to rail against it in the twenty-first century.

5. “Instant Replay,” Baseball Reference Bullpen, Accessed June 20, 2021. https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Instant_replay.

6. Tyler Conway, “Rob Manfred: Fans Acted Like MLB Rule Changes Were ‘Crime Against Humanity’” Bleacher Report, September 2, 2020. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2907345-rob-manfred-fans-acted-like-mlb-rule-changes-were-crime-against-humanity.

7. “BASEBALL; Baseball Talks May Resume,” The New York Times, July 9, 1995.

8. Steve Moyer, “In America’s Pastime, Baseball Players Pass A Lot of Time,” Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2013. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323740804578597932341903720. From the article, “By WSJ calculations, a baseball fan will see 17 minutes and 58 seconds of action over the course of a three-hour game. This is roughly the equivalent of a TED Talk, a Broadway intermission or the missing section of the Watergate tapes. A similar WSJ study on NFL games in January 2010 found that the average action time for a football game was 11 minutes.”

9. Bob Baum, “Manfred says pace of game rules crucial to luring young fans,” AP News, February 23, 2015. Found in many places including https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/2015/02/23/manfred-says-pace-of-game-rules-crucial-to-luring-young-fans/23911063.

10. Timothy Rapp, “MLB to Use Pitch Clock for Minor League Games,” Bleacher Report, January 15, 2015. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2331469-mlb-to-use-pitch-clock-for-minor-league-games-latest-details-and-reation.

11. Paul Hagen, “New rules to speed up pace, replay,” MLB.com, February 20, 2015. https://www.mlb.com/news/mlb-announces-new-pace-of-game-initiatives-changes-to-instant-replay/c-109822622.

12. Some notable examples included Mike Hargrove, who earned the nickname “The Human Rain Delay,” and Chuck Knoblauch, whose 11-step between-pitches routine grew legendary as leadoff hitter for the turn-of-the-millennium Yankees. See Bob Sudyk, “Pokey Hargrove Streaks to Hot Start For Tribe,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1980: 33; and Buster Olney, “BASEBALL; Between Pitches (Twist, Tap), a Game Within the Game,” The New York Times, August 22, 1999. “Before every pitch, Knoblauch steps out of the batter’s box to go through this elaborate preening, the pitcher waiting all the while.” https://www.nytimes.com/1999/08/22/sports/baseball-between-pitches-twist-tap-a-game-within-the-game.html.

13. Jayson Stark, “MLB Commissioner Ron Manfred unhappy with length of games.” ESPN.com, May 17, 2016. https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/15575004/mlb-commissioner-rob-manfred-unhappy-increased-length-games.

14. Mike Axisa, “Commissioner Rob Manfred confirms new pace of play rules coming to MLB in 2018,” CBSSports.com, November, 16, 2017. https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/commissioner-rob-manfred-confirms-new-pace-of-play-rules-coming-to-mlb-in-2018.

15. “2019 MLB Rule Changes Unveiled,” Ballpark Digest, March 14, 2019. https://ballparkdigest.com/2019/03/14/2019-mlb-rule-changes-unveiled.

16. Cliff Corcoran, “The new 3-batter minimum rule won’t speed up games but will have negative unintended consequences,” The Athletic, January 23, 2020. https://theathletic.com/1555626/2020/01/23/the-new-3-batter-minimum-rule-wont-speed-up-games-but-will-have-negative-unintended-consequences.

17. Alden Gonzalez and Jesse Rogers, “Sticky Stuff 101: Everything you need to know as MLB’s foreign substance crackdown begins,” ESPN.com, June 22, 2021. https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/31660574/sticky-stuff-101-everything-need-know-mlb-foreign-substance-crackdown-begins.

18. Teddy Cahill, “NCAA Commitee Approves Pitch Clock for College Baseball in 2020,” Baseball America, August 14, 2019. https://www.baseballamerica.com/stories/ncaa-committee-approves-pitch-clock-for-college-baseball-in-2020.

19. Craig Calcaterra, “Major League Baseball Creates a Pace of Game Committee,” NBCSports.com, September 22, 2014. https://mlb.nbcsports.com/2014/09/22/major-league-baseball-creates-a-pace-of-game-committee.

20. Tom Verducci, “How MLB could learn from Atlantic League in speeding up the game,” Sports Illustrated, August 5, 2014. https://www.si.com/mlb/2014/08/05/atlantic-league-pace-of-play-mlb.

21. Rick White, personal interview, May 17, 2021.

22. Rick White, personal interview, May 17, 2021.

23. J.J. Cooper, “Cooper: Atlantic League Rule Changes Aren’t As Noticeable As You’d Expect,” Baseball America, August 21, 2019. https://www.baseballamerica.com/stories/cooper-atlantic-league-rule-changes-aren-t-as-noticeable-as-you-d-expect.

24. J.J. Cooper, “New Mound Distance, Modified DH Among Atlantic League Rule Changes For 2021,” Baseball America, April 14, 2021. https://www.baseballamerica.com/stories/new-mound-distance-modified-dh-among-atlantic-league-rule-changes-for-2021.

25. Alek Z. Diffendaffer, Jonathan S. Slowik, Karen Hart, James R. Andrews, Jeffrey R. Dugas, E. Lyle Cain Jr, Glenn S. Fleisig, “The influence of baseball pitching distance on pitching biomechanics, pitch velocity, and ball movement,” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, February 8, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32063509.

26. Rick White, personal interview, May 17, 2021.

27. Jacob Bogage, “National Baseball Hall of Fame accepts Atlantic League ‘robo ump’ items,” Washington Post, July 25, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2019/07/25/national-baseball-hall-fame-accepts-atlantic-league-robo-ump-items.

28. Cooper, “Atlantic League Rule Changes Aren’t As Noticeable As You’d Expect.”

29. Fred DeJesus, personal interview, May 20, 2021.

30. Fred DeJesus, personal interview, May 20, 2021.

31. Just one example: “Boston closer Papelbon again fined for slow play,” Reuters, September 4, 2009. https:// www.reuters.com/article/us-baseball-redsox-papelbon/boston-closer-papelbon-again-fined-for-slow-play-idUSTRE58364W20090904.

32. David Fleming, “Tall tales: Getting an athlete’s real measurements is rarely easy,” ESPN: The Magazine, June 27, 2018. https://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/23913544/the-body-issue-getting-athlete-real-measurements-rarely-easy.

33. Mike Gross, “The Atlantic League, the changeable strike zone, and the quest to revive baseball,” Lancaster Online, May 29, 2021. https://lancasteronline.com/sports/local_sports/the-atlantic-league-the-changeable-strike-zone-and-the-quest-to-revive-baseball-column/article_1f1dbc74-c0c1-11eb-b8d1-07c763d7c466.html.

34. Andre Gueziec, “Tracking Pitches for Broadcast Television,” Computer, March 2002. http://baseball.physics.illinois.edu/TrackingBaseballs.pdf.

35. Press Release, Sony Electronics, “Hawk-Eye Innovations and MLB Introduce Next-Gen Baseball Tracking and Analytics Platform,” August 20, 2020. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/hawk-eye-innovations-and-mlb-introduce-next-gen-baseball-tracking-and-analytics-platform-301115828.html.

36. Dayn Perry, “MLB seems to think its broadcast audience is more important than fans at the ballpark,” CBSSports.com, February 21, 2018. https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/mlb-seems-to-think-its-broadcast-audience-is-more-important-than-fans-at-the-ballpark.

37. Graham Goldbeck, Marc Squire, Sid Sethupathi, “MLB Statcast Player Pose Tracking and Visualization,” SABR Virtual Analytics Conference, March 14, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uLbzUkNi7oU.

38. When I mentioned this vision of the future to Atlantic League umpire Fred DeJesus, his comment was, “I agree: that signal should come out of Secaucus and you could have a buzzer at the plate guy’s hip. But you’ll have guys who say ‘the buzzer didn’t work’ or ‘we didn’t get to it.’ You think Joe West is going to say he felt the buzzer? Absolutely not. Angel Hernandez is going to say he felt the buzzer? No way!” It’ll take a new generation of umpires who have benefited from technological feedback to accept these changes. As it is, studies have shown that younger umpires — who came up in an era when they’ve always had some form of pitch tracking, be it QuesTec, Pitch F/x, or Statcast — call balls and strikes more accurately than older, more experienced ones, likely because of the beneficial effect of that feedback. See Mark T. Williams, “MLB Umpires Missed 34,294 Ball-Strike Calls in 2018. Bring on Robo-umps?” BU Today, April 8, 2019.

39. Dr. Meredith Wills, “How One Tiny Change to the Baseball May Have Led to Both the Home Run Surge and the Rise in Pitcher Blisters,” The Athletic, June 6, 2018. https://theathletic.com/381544/2018/06/06/how-one-tiny-change-to-the-baseball-may-have-led-to-both-the-home-run-surge-and-the-rise-in-pitcher-blisters; Maria Armental, “MLB Buys Rawlings from Newell Brands for $395 Million,” Wall Street Journal, June 5, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/newell-brands-to-sell-rawlings-brands-for-395-million-1528203488.

40. Mark Feinsand, “MLB to Alter Baseballs for 2021,” MLB.com, February 8, 2021. https://www.mlb.com/news/mlb-to-alter-baseballs-for-2021.

41. Thus far in 2021 homers are down slightly, from 1.39 per team game in 2019 to 1.17 now, but the season is not over yet and offense tends to heat up with the weather. As noted by J.J. Cooper, though, the trend of more homers, walks, and strikeouts and fewer balls in play and lower batting averages is not just being seen in MLB, but in college baseball, too, where the ball was not changed. J.J. Cooper, “Home Runs, Strikeouts and Low Averages Are Trending Throughout Baseball,” Baseball America, May 26, 2021. https://www.baseballamerica.com/stories/home-runs-strikeouts-and-low-averages-are-trending-throughout-baseball.

42. Milicent L. Hathaway, “Trends in Heights and Weights,” Yearbook of Agriculture, 1959, 181. https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/IND43861419/PDF.

43. Nate Silver, “Does Size Matter?” Baseball Prospectus, April 27, 2005. https://www.baseballprospectus.com/news/article/3979/lies-damned-lies-does-size-matter.

44. Chelsea Janes, “MLB’s offensive woes are complicated, and they don’t appear to be going away,” Washington Post, May 17, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2021/05/17/mlb-offense-complicated.

45. Stew Thornley, Personal Interview, May 17, 2021, follow-up email June 23.

46. Associated Press, “Home Run Derby, not extra innings will decide Pioneer League games this season,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 27, 2021. https://www.sltrib.com/sports/2021/04/27/home-run-derby-not-extra.

47. Stew Thornley, the official scorer for the Minnesota Twins and longtime SABR member and rules historian, spoke to me for this article. His words: “Using terms like ‘abomination’ for the designated hitter is just overblown.” But people do.

48. “Messrs. Temple and Spalding Agree That the Pitcher Should be Exempt From Batting,” Sporting Life, December 19, 1891, 1.

49. Ryan Romano, “Pitchers are Hitting Even Worse,” Beyond the Boxscore, April 20, 2015. https://www.beyondtheboxscore.com/2015/4/20/8448085/pitchers-are-hitting-worse-mlb.