The Saga of J.R. Richard’s Debut: Blowing Away 15 Sticks at Candlestick

This article was written by Dan VanDeMortel

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Space Age (Houston, 2014)

When Houston Astros right-handed flamethrower James Rodney Richard, the number two pick in the June 1969 draft, debuted against the San Francisco Giants at Candlestick Park on September 5, 1971, he did so in relative anonymity. He received no television coverage, and no radio broadcast beyond the clubs’ local markets. Fans were unaware of his 100-mph fastball or 94-mph slider.1 And Willie Mays and baseball’s fourth-best offense awaited him. Think of it as the polar opposite of Stephen Strasburg’s uber-hyped 2010 debut against the Pittsburgh Pirates (then MLB’s second-worst offense).

Richard accomplished what Strasburg did not: striking out 15 batters to tie the 1954 debut record set by Brooklyn Dodger Karl Spooner—also against Mays’s Giants. Unfortunately, scant media attention, future pitching heroics, and well-chronicled personal tribulations shadowed Richard’s debut, obscuring an intriguing tale with its own Strasburg-like dominance.2

Richard accomplished what Strasburg did not: striking out 15 batters to tie the 1954 debut record set by Brooklyn Dodger Karl Spooner—also against Mays’s Giants. Unfortunately, scant media attention, future pitching heroics, and well-chronicled personal tribulations shadowed Richard’s debut, obscuring an intriguing tale with its own Strasburg-like dominance.2

Richard’s path to Candlestick began in 1950, when he was born in rural Vienna, Louisiana. About growing up in a self-described middle-class black family, Richard reflected, “My father and I had a long talk one day and he said, ‘Have more for your family than I have for you.’ And somehow it came to me that I wanted to be the best at everything I did and never take nothing for granted.”3

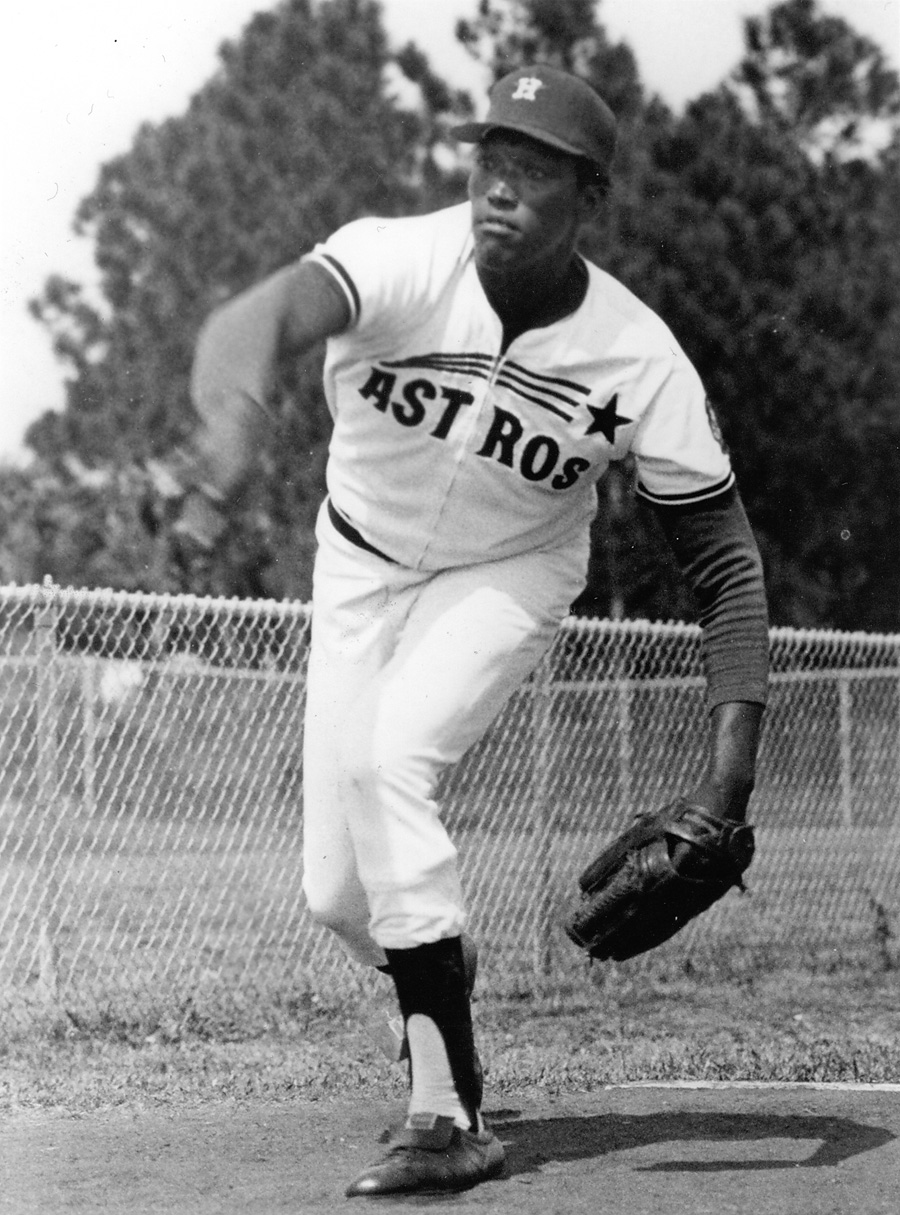

Cemented with determination and athleticism housed inside a gangly frame—he graduated at 6’8″, 222 pounds—Richard took nearby Ruston’s basketball, football, and baseball teams by storm, earning multiple scholarship offers. Once drafted, Richard chose baseball, primarily due to receiving $100,000 bonus money. Astros player personnel director Tal Smith opined that Richard had an arm “a scout might see once about every 500,000 miles.”4

Richard progressed quickly through the minors, advancing to the Astros’ Triple-A Oklahoma City 89ers in 1971, where he led the league in strikeouts and ERA. Control issues occasionally plagued him, but with an impressive arsenal of fastballs, sliders, and curves, “J.R.” or “The Big Fellow,” as hailed by teammates, was promoted to the Astros on September 1. He later remembered it felt good to be in the majors, but “I didn’t feel a jolt or surge…. It wasn’t a big change because of my attitude. I just wanted to be the best.”5

He joined a team 16 games out of first, fighting for fourth place in the NL’s Western Division. Despite a league second-best 3.13 ERA, Houston was doomed to mediocrity by anemic offense, key injuries, and players’ contretemps with manager Harry “The Hat” Walker. Richard was informed the following day that he would start Sunday’s second game of a doubleheader against the Giants. Departing Houston that evening for a four-game series, the team arrived sleepily in San Francisco early Friday morning.

The club they encountered was formidable, spearheaded by four future Cooperstown inductees: 40-years-young center fielder Mays, first baseman Willie McCovey, and pitchers Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry. Right behind were five-tool star Bobby Bonds and rookie masher Dave Kingman. Although the team had cooled after a blistering 37–14 start, San Francisco maintained a large first-place lead en route to winning its division and compiling a second best 51–30 home record. The Giants were patient, too, as evidenced by leading the NL in walks. Spoiler alert: The Giants also led the major leagues in strikeouts.

The first match that Sunday set the table for the second. In the first inning, McCovey suffered a split left hand while attempting to field a vicious bouncer. With backup first baseman Kingman absent with appendicitis, the versatile Mays moved to first. Having few other options on short notice, manager Charlie Fox would be forced to play Mays there for both games. The Astros took advantage, squeaking out a 1–0 victory, emphatically stamped by starter Jack Billingham, who struck out a season-high 11. Keep that number in mind.

Around 3:00pm, Richard warmed up in the Astros bullpen along the left-field line. He would have been hard-pressed to envision a more alien landscape for his debut. Candlestick had bid adieu to the open outfield expanse of the 1960s, when Mays’s cap seemingly always fell to the grass as he snagged every fly ball. Instead, the football 49ers had recently abandoned cramped Kezar Stadium in favor of this automobile-friendly location on the city’s edge. The result? Goodbye baseball-only park, hello ongoing conversion to a multi-use stadium. Candlestick’s renovations included rock-hard AstroTurf, an enclosing outfield area negating visibility of the outside world, and unfinished construction along the upper deck resembling “a construction job deserted by the hardhats after a hot labor-management dispute.”6

The weather, too, contributed an otherworldly vibe. The previous day’s yearly high of 85 had fallen 19 degrees, as coalescing marine fog hovered along the Pacific, waiting to steamroll inland. With the fog came “The Hawk,” the nickname for gusts that frequently buffeted day games, the talons of which arrived habitually around three, turning the bullpen into a breezy swirl of food wrappers, plastics, and anything else lighter than a small dog.

Blessedly, the fog lingered somewhere beyond the upper deck overhang, permitting sunshine. Damningly, The Hawk was in flight, swirling at 10–20 mph, perhaps harder in unlucky microclimates. As the San Francisco Chronicle’s Bob Stevens acutely described, it was a “sometimes chill-blasted day.”7

Whether due to the Hawk, nervousness, or innate wildness, Richard captured Fox’s attention: “I watched him warm up in the bullpen. He threw at least a dozen balls that the catcher couldn’t reach.”8 After finishing, Richard returned to the dugout, then watched as Jim Willoughby, also making his debut, shut Houston down in the top of the first.

Switch-hitter Ken Henderson led off for the Giants. How did one of the tallest pitchers in history appear to him, catcher Larry Howard, and home plate umpire Billy Williams? Stevens observed Richard came off the mound “like a huge crane.”9 As Dave Parker would later describe: “When he…let the ball go, he look[ed] like he [was] 10 feet away from you instead of 60[, which caused] you to lean a little bit and [made] you think you [had] to swing the bat quicker.”10 Perhaps the Pirates’ Richie Hebner summed it up best: “He [was] so close to the plate when he finish[ed] his windup that I [was] thankful he didn’t eat onions before the game.”11

Somehow, Henderson stroked a single to center. Switch-hitting Tito Fuentes was not so fortunate, grounding out to advance Henderson to second. Next up, Mays: a god compared to the Astros neophyte. Lacking the bat speed of years past, Mays nonetheless entered the game at .294/.436/.521, eventually compiling the eighth-best wins above replacement (WAR) and best on-base percentage in the league.12 A storybook battle of youth vs. experience.

Somehow, Henderson stroked a single to center. Switch-hitting Tito Fuentes was not so fortunate, grounding out to advance Henderson to second. Next up, Mays: a god compared to the Astros neophyte. Lacking the bat speed of years past, Mays nonetheless entered the game at .294/.436/.521, eventually compiling the eighth-best wins above replacement (WAR) and best on-base percentage in the league.12 A storybook battle of youth vs. experience.

Youth won. Mays struck out swinging. Richard had little time to savor his first “K,” though. The strikeout-prone Bonds beat out an infield bouncer, then scored with Henderson on an RBI double by hot-hitting “Dirty” Al Gallagher for a 2–0 Giants lead.13

What ensued is a classic baseball legend in three acts. In act one, Astros first base coach Hub Kittle recalled, “The first time Mays came to bat, J.R. just threw that fastball by him.” As Mays returned to first for the second inning, he asked Kittle in a high-pitched voice, “Hubert! My Lord! Who was that? He nearly scared me half to death! Where’d you get him?”14

Leaving act one, after the Astros failed to score, Richard answered, issuing a walk but nailing Willoughby for his second swinging strikeout. In the third, the Astros discovered their bats. After Richard grounded out in his inaugural at bat, Houston tied the score on RBI singles by Cesar Geronimo and Cesar Cedeño. The Giants failed to respond in kind. Translation: Richard struck out the side of Fuentes, Mays, and Bonds, with Mays looking at a called strike three. At this point, turning to act two, Kittle recalled Mays shaking his head while returning to first.15

The Astros added another run in the fourth for a 3–2 lead on an RBI single by Howard, Richard’s former Oklahoma City batterymate. With that, Fox summoned rookie Jim Barr to successfully shut the door. Richard responded in the bottom frame by again allowing no runs. San Francisco achieved a moral victory, however: No Giant struck out.

Houston widened its margin in the fifth with its last two runs of the day on RBIs again by Geronimo and Cedeño. Armed with a 5–2 cushion, Richard took charge. Catcher Dick Dietz, inserted on a double-switch in the top of the inning, joined the strikeout club, going down swinging. After a Henderson out, Fuentes initiated a rally with a single to left-center, bringing up Mays. We will never know how vociferously Giants’ fans cheered for home run number 646 off his bat, but surely a collective groan escaped when Richard strangled hope, striking out Mays swinging.

Now comes act three. After striking out, Mays slowly walked to first, exclaiming, “Hubert! You know what! Nobody’s ever struck out Mays four times, have they? Well, I tell you what. That guy ain’t going to strike me out again, because I ain’t playing anymore.”16 According to Kittle, Mays then took himself out of the game at some unspecified point.17 Was Mays serious? More to be revealed.

San Francisco’s bats disappeared once more in the sixth as Richard navigated around his second walk by striking out Bonds again and light-hitting Jimmy Rosario, both on swinging third strikes. With no Astros runs or rendition of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” or “God Bless America” to delay him in the seventh, Richard returned to the bump, sitting on nine strikeouts. Make that 10, as Dietz looked at a called third strike.

Rookie pitcher Steve Stone overcame a Mays error to escape damage in the eighth, bringing up the heart of the Giants order. Whether from newfound confidence or lacking an exit strategy, Mays grabbed his bat and opened proceedings with a walk. He advanced to second on a passed ball, and later scampered to third on a Bonds foul fly to first baseman John Mayberry—incredibly shrewd baserunning by the still-speedy veteran.18 Richard seized momentum by striking out Gallagher looking. Mays grabbed it right back, however, scoring when third baseman Denis Menke booted a Chris Speier grounder. After an infield single advanced Speier to second, Fox called catcher Fran Healy from the bullpen to pinch hit. Richard quickly fell behind 3–0 on two curves, “then went back to his hummer and simply blew the next three casts past [him],” the last strike looking.19 As an awestruck Healy recalled: “…I [came] back to the dugout and [Fox] said, ‘We have his pitches.’ (Richard was tipping off his pitches.) And I said, ‘So do I.’ Jeez, he was throwing a hundred miles an hour.”20

In the bottom of the ninth, pitching in shadows covering the infield, Richard stood on the cusp of history with 12 strikeouts. Mays was due up fourth.

First batter? Dietz, again. Result: same as it ever was, strikeout 13, swinging.

Second batter? Henderson. A contact hitter who would whiff only 76 times in 598 plate appearances, he hadn’t yet struck out that day. Result: strikeout 14, swinging.

Next potential victim? Subbing for Fuentes in the eighth, Hal Lanier was the quintessential 1970s punchless-hitting infielder, but entering the game with 24 strikeouts in 205 plate appearances, he was hardly a swing-and-miss machine. Plus, he was assisted by the distracting influence of Mays on deck. Or, had Mays quit?

No. Baseball writer Rob Neyer correctly observed in 2008 that with the Giants contesting a close game in a pennant race, the notion of Mays removing himself seemed “preposterous, at the very least.”21 Hindsight in 2014 conclusively reveals Kittle’s tale as a great fishing story, but a story nonetheless. First of all, Mays had struck out four times on April 24 and June 18, something he would easily remember. Second, no reporters mentioned another Giant waiting on deck, certainly a noticeable development given how Mays’s movements were analyzed like the Zapruder film. Lastly, if Mays departed and the game became tied, who would play first? McCovey and Kingman were unavailable. When asked afterward who would play first going forward, Fox answered Mays, griping “Who else is there who can play it?”22 Thus, a matchup for the ages waited in the wings.

No. Baseball writer Rob Neyer correctly observed in 2008 that with the Giants contesting a close game in a pennant race, the notion of Mays removing himself seemed “preposterous, at the very least.”21 Hindsight in 2014 conclusively reveals Kittle’s tale as a great fishing story, but a story nonetheless. First of all, Mays had struck out four times on April 24 and June 18, something he would easily remember. Second, no reporters mentioned another Giant waiting on deck, certainly a noticeable development given how Mays’s movements were analyzed like the Zapruder film. Lastly, if Mays departed and the game became tied, who would play first? McCovey and Kingman were unavailable. When asked afterward who would play first going forward, Fox answered Mays, griping “Who else is there who can play it?”22 Thus, a matchup for the ages waited in the wings.

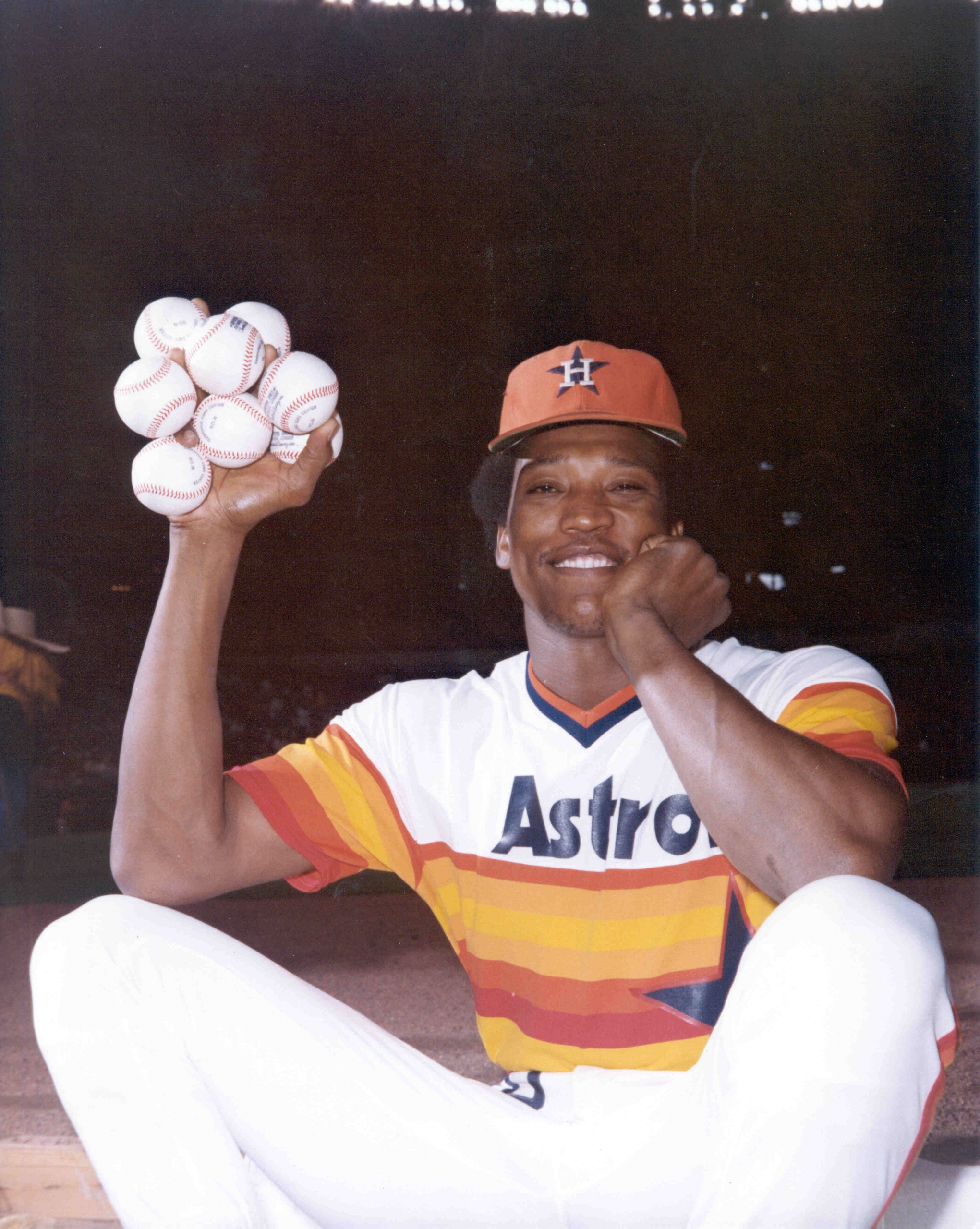

Alas, Lanier failed to comply. Strikeout 15! Richard tied the record at the two-hour, 39-minute mark on his 155th pitch, a swinging third strike, “seemingly still throwing with the same power as in the early innings.”23, 24 As Lanier retreated to the dugout, the Astros “rushed out to congratulate their new, instant hero.”25 Billingham and Richard embraced, for their combined 26 strikeouts still ties the record for the most strikeouts thrown by a team’s starters in a twin bill: a safe standard given the modern disappearance of doubleheaders.

In the clubhouse, reporters flocked to Richard like a new Hollywood star. Stevens observed, “…very few Giants…dared dig in on him, and you certainly can’t fault them for that.”26 The San Jose Mercury News and Houston Chronicle both marveled how Giants batters took many called strikes while stepping away from the plate.27 The Houston Post even compared him to fellow Louisianan Vida Blue, the 1971 American League Most Valuable Player and Cy Young Award winner.28

Mays chimed in less enthusiastically. Concurring with Bonds’s postgame assessment that Richard was not quite as fast as anticipated, he dryly credited Richard with always being around the plate.29 His subdued remarks remain incongruous with his three-strikeout workday and whatever joke or threat he may have offered to encourage Kittle’s storytelling abilities.

Postgame sabermetric insights were non-existent at the time. Current tools rate Richard a 75 game score, which tied Strasburg’s effort, primarily since The Big Fellow pitched a complete game, while Strasburg’s was a pitch count-limited seven-innings, with 94 pitches and no walks.30 Both trailed Spooner’s 93 game score for a three-hit shutout on 143 pitches. Spooner’s 1954 performance, while impressive and historic, slightly trails Richard’s accomplishment in two key respects. First, he pitched at home in Brooklyn before a spring training-like 3,256 crowd. Second, the Giants had clinched the NL pennant on September 20, just two days earlier. As 1971 Giants pitching coach Larry Jansen recalled after watching Richard’s performance, “We had quite a party the night before Spooner pitched. There weren’t too many regulars in the lineup that day.”31

As for Richard’s reaction, he was as cool as the proverbial other side of the pillow: “I wasn’t keeping track of the strikeouts. I didn’t think a lot about facing Mays, Bobby Bonds and other good hitters. I just felt if something was going to happen, it was going to happen.32

“There wasn’t anything to get nervous about. They gave me the ball. After that there was nothing to do about it but to pitch…. I wasn’t thinking strikeout today. Actually, I just tried to get the ball over the plate,” he politely added, agreeing with Howard that he did not have the elite fastball he had that day in Oklahoma City when he struck out 17—with 16 in the first six innings before developing a finger blister.33 As for comparisons to Blue, he refused to take the bait: “Others have done that, not me.”34

Richard explained laconically that he threw fastballs and sliders to Mays, and offered no clichés then or now about tying the record of, to him, an unknown ballplayer from a time when baseball was in black and white, literally and figuratively.35 Yet the memory of stifling Mays, the connective tissue between the two events, still remains.36 As Richard observed years later, “My biggest game was my major league debut…. I didn’t realize what was going on until it was over…. All I could remember was Willie Mays going down swinging. My slider moved this much (holding his hands about five feet apart).”37

The promise Richard demonstrated that day slowly flowered. Overcoming wildness, inconsistency, and injuries, he finally secured a rotation spot in 1975, won 20 games in 1976 and struck out over 300 batters in 1978 and 1979. In 1980 he started the All-Star Game for the NL. On the mound, he “went out there with the mentality if you beat me I’m gonna die trying. I was willing to give my life for it.”38

He very nearly did. Days after the All-Star Game, Richard suffered a stroke. His reputation was smeared in a miasma of medical complications and media-fueled accusations of malingering: at best inaccurate, at worst racist. After failed comeback attempts, he was cut by the Astros in 1984. A downward personal spiral ultimately left him homeless at times under a bridge in Houston.

Then, at his nadir, came redemption. With help from friends and religious inspiration, he recovered, and he began counseling in Houston-area churches and mentoring youths on baseball and life. In 2012, he was inducted into the Astros’ Walk of Fame. At peace, he is now “peacock proud and honeymoon happy” enough to say with levity and Southern sass, “I’m the only man in the world who [could] throw a ball through a car wash and never get it wet.”39

DAN VanDeMORTEL became a Giants fan in Upstate New York and moved to San Francisco to follow the team more closely. He has written extensively on Northern Ireland political affairs, and his Giants-related writing has appeared in San Francisco’s “Nob Hill Gazette.” He is currently writing a book on the 1971 Giants and welcomes feedback at giants1971@yahoo.com.

Sources

All statistics are cited from or calculated from Baseball-Reference.com (http://www.baseball-reference.com) unless otherwise noted. The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide (1972) also provided helpful background.

Notes

1. Pitch speeds are the consensus from various referenced speeds spanning Richard’s career.

2. The New York Times recorded “Jim” Richard’s accomplishment in one paragraph sans headline: The New York Times, September 6, 1971. The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times ran brief wire service accounts sans quotes from participants: “Astros’ Pitchers Stop Giants Twice,” Washington Post, September 6, 1971; “Astros Sweep Giants; Rookie Strikes Out 15,” Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1971.

3. Blake Jackson, “The Collected Wisdom of James Rodney Richard,” NewsOK, June 18, 2006, http://newsok.com/the-collected-wisdom-of-james-rodney-richard/article/1875003.

4. Wil A. Linkugel and Edward J. Pappas, They Tasted Glory: Among the Missing at the Baseball Hall of Fame (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), 145.

5. Jackson, op. cit.; Dave Hollander, “J.R. Richard: The Human Condition,” Houston Press, September 2, 2004, www.houstonpress.com/2004-09- 02/news/j-r-richard-the-human-condition/.

6. Charles McCabe, “The New Candlestick,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 13, 1971.

7. Bob Stevens, “Giants Lose 2; McCovey Hurt,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 6, 1971.

8. Bucky Walter, “15 Strikeouts in Astro’s 1st Start,” San Francisco Examiner, September 6, 1971.

9. Stevens, op. cit.

10. Ron Reid, “Sweet Whiff of Success,” Sports Illustrated, September 4, 1978, http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/

MAG1135814/index.htm.

11. Harry Shattuck, “King Richard a Real Highness in Houston,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1979.

12. Mays struck out a career-high 123 times in 1971.

13. Bonds set a then major league record with 187 strikeouts in 1969 and broke it with 189 in 1970. He was on pace for an improved total of 137 in 1971.

14. All Kittle quotes are from SABR’s BioProject: Hubert Kittle, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/4d152362 (see fn 129). Phil Pepe, Talkin’ Baseball, An Oral History of Baseball in the 1970s (New York: Ballantine Books, 1998), 53–4 contains a similar version. This article opts for SABR’s version over most, but not all, of Pepe’s, being that it is an earlier version with more detail, taken from a 1992 television interview.

15. SABR BioProject: Hubert Kittle, op cit.

16. Ibid.

17. Pepe, op. cit., 53-54.

18. Baseball-Reference.com indicates Howard was responsible for two passed balls in this game. However, all newspaper box scores indicate only one; no game account mentions a second.

19. Stevens, op. cit.; Pepe, op. cit., 53.

20. Pepe, op. cit., 53.

21. Rob Neyer, Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Legends (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008), 141–2.

22. Dick Friendlich, “Mays Back to First,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 6, 1971. Fox alluded to the possible future deployment of backup catcher Russ Gibson or Lanier to first: Dick O’Connor, “Giants, Dodgers Clash Tonight,” Palo Alto Times, September 6, 1971. But, Gibson had already been replaced by Dietz and Fox’s options for replacing Lanier at second were limited. Recent triple-A callups infielder Chris Arnold and outfielder Bernie Williams were the only available position players. Using either in some convoluted switch to honor a Mays request to leave the game would have weakened the lineup offensively and defensively, and given Fox even fewer bench options in the event of extra innings or injuries.

23. An exact pitch count is not available. This approximation was derived via Tom Tango’s Basic Pitch Count Estimator, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_pitch_count_estimator.

24. John Wilson, “Richard Fans 15 in Sweep,” Houston Chronicle, September 6, 1971, www.astrosdaily.com/history.

25. Joe Heiling, “Richard Fans 15, Ties Rookie Mark for First MLB Start,” September 6, 1971, www.astrosdaily.com/history.

26. Stevens, op. cit.

27. Jack Hanley, “Twin Loss for Giants,” San Jose Mercury News, September 6, 1971; Wilson, op. cit., “Richard Fans 15 in Sweep.”

28. Heiling, op. cit.

29. O’Connor, op. cit.

30. Game score is a metric devised by sabermetrican Bill James to numerically evaluate the strength of a starting pitcher’s performance. The higher the score, the more successful the performance. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Game_score.

31. O’Connor, op. cit. Left fielder Monte Irvin was the only Giants starter to play the entire game; all others rested or were confined to two or fewer at bats. Jansen’s recollection on timing of the Giants celebration(s) could be slightly off, but even The Sporting News cautioned that Spooner benefited from facing a weak lineup and a Giants team “bound to be more or less indifferent” after clinching the pennant, with some batters possibly “swinging at the first pitch to get [the game] over with.” Bill Roeder, “$600 Dollar Spooner Looks Like Million in Fall Debut,” The Sporting News, Oct. 6, 1954. Sadly, Spooner’s career abruptly ended the following season due to a throwing-shoulder injury.

32. Pat Frizzell, “Giants Lose Mac for One Week,” Oakland Tribune, September 6, 1971.

33. Walter, op. cit.; John Wilson, “J.R. Gives Astros Happy Expectations,” The Sporting News, November 27, 1971.

34. Heiling, op. cit.

35. Walter, op. cit.

36. Mays singled in two at bats versus Spooner with no strikeouts.

37. Jackson, op. cit.

38. Wesley Wright, Past Meets Present Interview of J.R. Richard, MLB.com, August 6, 2012, http://m.mlb.com/video/topic/0/v23666167/past-meets-present-jr-richard-and-wesley-wright.

39. Zachary Levine, “J.R. Richard Appreciates Astros Honor But Wants More,” Ultimate Astros, May 31, 2012, http://blog.chron.com/ultimateastros/2012/05/31/j-r-richard-appreciates-astros-honor-but-wants-more; Darryl Hamilton, Joe Magrane, and Paul Severino Interview of J.R. Richard at 2013 Urban Invitational, MLB.com, February 23, 2013, http://m.mlb.com/video/topic/15886078/v25615153/jr-richard-on- importance-of-having-a-good-mindset.