The ‘Savior’ Does Not Answer Letters: Dave Hoskins and the Uneven, Unheralded, and Unfinished Integration of the Texas League

This article was written by Jason A. Schwartz

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Texas and Beyond (2025)

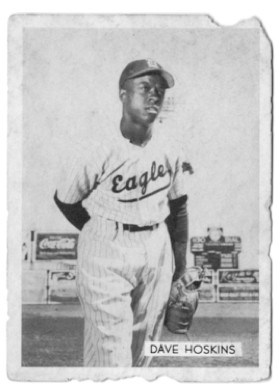

1952 Globe Printing baseball card of Dave Hoskins. (Author’s Collection)

On March 19, 1951, a group of 20 young Black ballplayers gathered on a cold day in West Texas for what was then billed as an “All-Negro Tryout Camp.” By day’s end, two players—outfielder Connie Heard and shortstop J.W. Wingate—impressed manager Jay Haney sufficiently as to earn invitations to camp.

Neither the tryout nor its results were remarkable in any way, even in the South, except for one detail. The team hosting the tryout, the Lamesa Lobos of the Class C West Texas-New Mexico League, was entirely White.2 Four years after Jackie, the seeds of integration had reached the Lone Star State. Or had they?

Though Haney had hoped to land players of Cuban ancestry, perhaps to limit backlash, he seemed otherwise genuine in his openness, if not enthusiasm, to integrate the squad, stating, “Negroes can play ball and the time is not far off when Negroes will be playing on White teams in Texas.” His time in the military helped shape this view. “I lost my opposition to [Black players] when I played with and against them in service ball.”3

Haney backed up his words with action, playing both Heard and Wingate in the Lobos’ spring training opener.4 However, less than two weeks later, Haney sent both players packing. Though he found them to be “excellent types,” he concluded that neither had the skills to compete at the Class C level.

As much as the Black players’ dismissal, right down to the rationale, echoed any number of previous perfunctory “attempts” at integration, a plot twist followed. Not only was Wingate back with the team by the season opener, but he was one of three Black players on the Lobos Opening Day roster.5 (The others were pitcher Roberto Leyva and catcher Douglas McBean, both Black Cubans.) Both Wingate and McBean saw action in the opener.6 The date was April 21, 1951: Organized Baseball in Texas had officially integrated, and the world did not end.

The integration of the Lobos produced far more whimper than bang. With some irony, Cubans Leyva and McBean were released within the week for failing to understand Haney’s instructions in English.7 A month later, the Lobos handed Wingate his unconditional release, and he was off to the Kansas City Monarchs.8 In a baseball eulogy doubling as prophecy, Collier Parris penned the following in his column of May 26:

Lamesa fans, being sturdy, southern hometowners to whom Negroes mean cotton pickers, shine boys, and car-washers, never did give Wingate a chance. Even refused to attend the home games because of his presence in the lineup. This treatment gave Negro baseball prospects quite a setback in Texas, made it difficult for others of his race to “break in” so far as this section of the country is concerned.9

How much or little of this history Dallas Eagles owner Dick Burnett, both emboldened and threatened by the impending arrival of the National Football League’s integrated Dallas Texans franchise amid hemorrhaging attendance league-wide (see Table 1), was aware of when he announced in January 1952 his plans to integrate the Double-A Texas League, all White since its establishment in 1888, is unknown.10

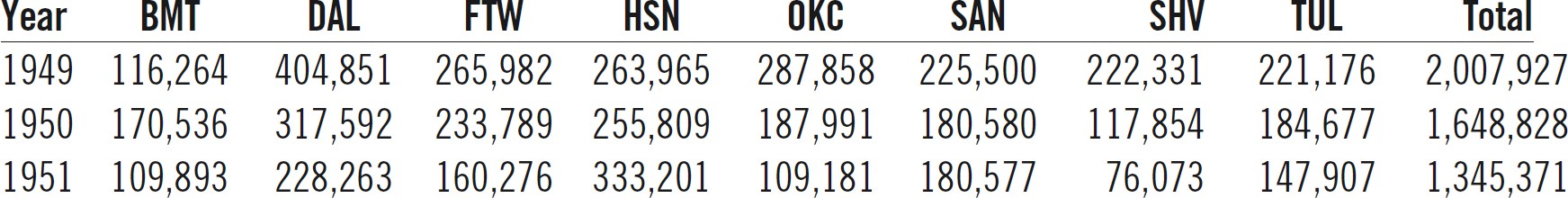

Table 1. Paid Attendance in Decline, Texas League, 1949-5111

What is known is that reaction around the league, outside of Shreveport, ranged from accepting to intrigued.

- John Reeves, president of the Fort Worth Cats, remarked simply enough that “time marches on,” at the same time acknowledging the unlikelihood that any Black players in the Dodgers system were suitable for the Cats.12

- Guy Airey, president of the Beaumont Roughnecks (later “Exporters”), expressed qualified support for the idea. “If Mr. Burnett intends to use Negro players to strengthen his Dallas team and also help the Negro race, fine. But if he plans to use Negro players simply for drawing cards, as gate attractions, I do not approve.” Airey added, “If Texas League Negro players are introduced in Dallas and other Texas League points, and I get a chance to sign an outstanding player, regardless of his color, I will do so.”13

- Art Routzong, business manager of the Houston Buffaloes, noted the Buffs had already played against Black players, presumably without incident, in exhibitions against the Brooklyn Dodgers and Milwaukee Braves.14

- Jimmy Humphries, president of the Oklahoma City Indians, declined to comment but committed the matter to further study.15

- Grayle Howlett, Jr., president of the Tulsa Oilers, recognized the value of Black players but preferred to follow rather than lead: “Negro players have come into organized baseball in recent years and made key contributions to winning clubs in both the major and minor leagues. Certainly we in Tulsa will do nothing less than any other clubs in the Texas League are doing in the quest for the winner which we all seek.”16

- Joe McShane, president of the San Antonio Missions, understood that integration was unstoppable. “It’s coming. The majors, including the Browns, are signing Negro ball players and putting them in their farm systems…” In a statement that could be read two ways, McShane added that “Any Negro who gets into the Texas League should be an outstanding player when he is here.”17

- Only Bonneau Peters, president of the Shreveport Sports, was openly defiant. He not only doubled down on segregation (“You can quote me as saying that the Shreveport club has no plans for using any Negro players.”) but added that even competing against integrated teams could be problematic.18

It was against this backdrop that the Dallas Eagles drew nearly 200 Black players, among them J.W. Wingate, to a February 12-15 tryout seeking what Burnett hoped might be “one or two players who can make the grade.”19, 20 Remarkably, but perhaps predictably, not a single player impressed the Eagles as good enough for AA ball. Of the tryout’s top three players (James Thomson, Johnnie Williams, Bobby Joe Fritz), Burnett stated, “We believe these boys are capable of Class C ball,” i.e., the Bakersfield Indians of the California League. “How far they go from there is strictly up to them.”21 (In fact, none of the three even made Bakersfield.22)

The script was again familiar, but—as in Lamesa— the story was not over. The Eagles ultimately reached agreement with two players who had not been at the tryout—Othello Renfroe and Ray Neil—to train with the club in Daytona Beach. Renfroe proved a no-show and Neil, a former Negro League all-star, was deemed not good enough.23 Still, Burnett was not one to give up easily. By late March, the Eagles owner had reached agreement with Hank Greenberg, general manager of the Eagles’ parent club, the Cleveland Indians, to send Mississippi native Dave Hoskins from camp with Indianapolis to Dallas instead.24

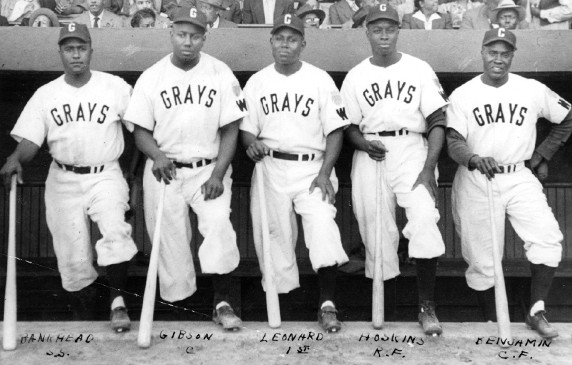

Homestead Grays Murderers’ Row of Sam Bankhead, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Dave Hoskins, and Jerry Benjamin. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Hoskins’ baseball credentials to that point had been quite impressive. A member of the Homestead Grays’ fabled Murderers’ Row, he had played for two pennant winners and a Negro League World Series champion between 1944 and 1946. Though the Grays blocked him from participating, Hoskins was also one of three Negro Leaguers—along with Jackie Robinson and Sam Jethroe—selected by Wendell Smith to try out with the Braves and Red Sox in 1945.25 And in 1948, Hoskins batted .393 for the Grand Rapids Jets, integrating the Central League in the process.26 Were it not for the number of White pitchers throwing at his head, Hoskins might have arrived in Dallas as an outfielder. Instead, self-preservation demanded that he arrive as a pitcher. “I was tired of having pitches thrown at me. I made up my mind that I would start throwing at other guys.”27

Though Burnett’s efforts at integration had fared poorly to this point, his firsthand experience with Hoskins led him to believe he might prove the “lone star” among so many also-rans. Hoskins had already pitched against Dallas that spring and retired all six batters he faced.28 Burnett’s faith in the curve-baller was further affirmed when Hoskins held the Boston Red Sox to two hits across four innings in his Eagles preseason debut.29 His first regular season start, on April 13, was less sharp but no less successful. Despite walking seven Tulsa Oilers, Hoskins allowed only one earned run in a 4-2 complete game victory. For good measure, he even notched a pair of singles.30 More significantly, he was the first Black player in the 57-year history of the Texas League.31

To say Hoskins gave Burnett everything he could have asked for is a massive understatement. In just over a month, Hoskins established himself as the league’s best pitcher, one of its leading hitters, and by far its top box office draw, both at home and on the road.32 Bolstered by Hoskins’ success, the Eagles added Wilkes-Barre (Cleveland Indians Single-A affiliate) ace and former New York Cuban Jose Santiago on May 17.33

None of this suggests Hoskins himself had it easy. A Black man in the Jim Crow South, Hoskins could neither eat at the same restaurants nor stay in the same hotels as teammates. Add to that the dependable contingent of White fans at every ballpark ready to greet “the Savior of the Texas League” with name-calling and hostility.34 The roughest destination was always Shreveport, where just a week after proposed legislation sought to bar integrated athletic competition statewide, even death threats entered the mix.35

Regardless, Hoskins kept on pitching, kept on winning, and kept on spinning league turnstiles at breakneck pace. The Oklahoma City club, which in January had relegated the matter of integration to “further study,” signed Birmingham Black Barons ace Bill Greason on July 28.36 As in the Jackie story, Greason’s July 31 debut made a team with the Indians nickname second to integrate. When Greason’s next start, August 3, paired him against Hoskins, the league witnessed not only its first ever matchup of Black pitchers but a season-high attendance of 11,007 to boot.37

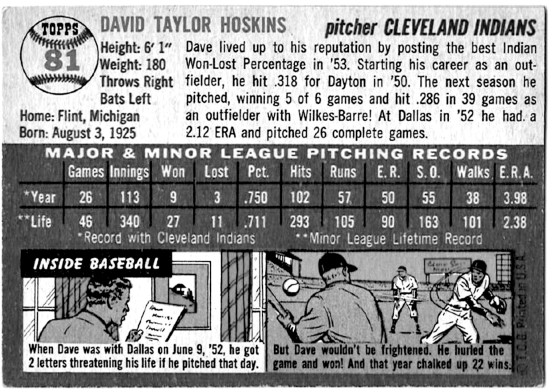

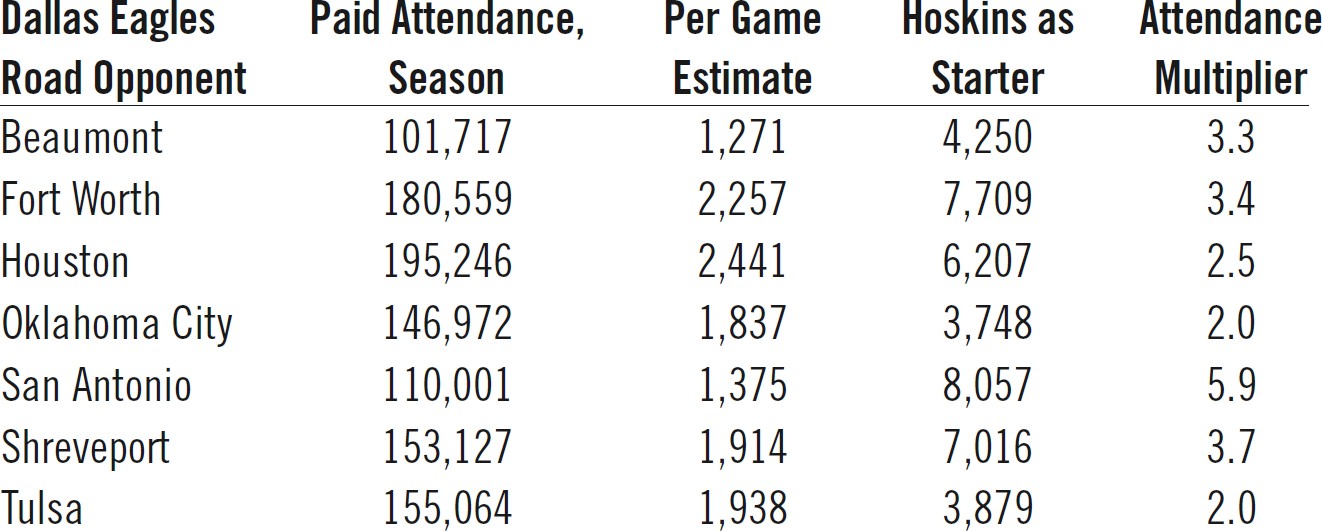

As the regular season wound to a close, Hoskins had not one but two nights held in his honor, the first by the Eagles’ archrival Fort Worth Cats. On cue, Hoskins obliged by winning his 20th game of the season, and his two hits temporarily raised his batting average to tops in the league, albeit unofficially due to limited at-bats. His numbers at season’s end: a 22-10 record, a 2.12 ERA, a .327 batting average, a first place finish for the Eagles, two postseason victories, and a doubling (or more!) of attendance everywhere he pitched, even Shreveport!38 See Table 2.

Not to be outdone, Santiago and Greason finished the season a combined 23-8 with earned run averages of 2.83 and 2.14 respectively, though neither approached Hoskins’ numbers at the plate. Either way, the success of the three hurlers left no doubt that Black players were more than capable of success in the Texas League. If there were any question remaining, maybe the players were too good…?

“Inside Baseball” cartoon, featuring death threats, on reverse of 1954 Topps Dave Hoskins baseball card. (Author’s collection)

Hoping for their own version of Dave Hoskins, two additional teams entered the 1953 season with integrated rosters. Chuck Harmon, who integrated the Cincinnati Reds a year later, integrated the Tulsa Oilers on April 9 and went on to finish sixth in the batting race and third in stolen bases.39 The very next day, future Milwaukee Brave Charlie White made history for the San Antonio Missions, starting at catcher and tallying a hit, a run, and an RBI.40 White was again part of history four days later, pairing with pitcher Harry Wilson to form the league’s first all-Black battery. As for Wilson, all he did that day was allow one run in 10 innings, collect two hits, and score the game’s winning run.41

Despite its proven success, integration across the rest of the league proceeded slowly, if at all. The Beaumont Exporters got the ball rolling in January 1954 by trading for Jim “Buster” Clarkson, who had enjoyed a monster season with Dallas in 1953. Clarkson, already 39 years old at the time of his April 9 Beaumont debut, went on to pace the circuit in home runs. Later that month, the Exporters added former Negro League all-star Jesse “Bill” Williams, though he played only eight games.42

May 27, 1954, marked the integration of the Houston club when Bob Boyd, acquired from the White Sox, doubled, tripled, and registered eight putouts at first base for the Buffs.43 He would bat .321 for the season. The Fort Worth Cats, initially dubious that any Black player in the Dodger system could assist them, finally integrated on April 18, 1955, with the insertion of future National League Most Valuable Player Maury Wills into the lineup.44 Table 3 provides a summary.

As for the Shreveport Sports, the team remained segregated all the way through its December 1957 exit from the league, following a last place finish and barely 500 fans per contest.45 In opting for disintegration over integration, team president Bonneau Peters— whom minor league officials anointed “King of Baseball” in 1959—was nothing if not a man of his word.

JASON A. SCHWARTZ is a member of the Emil Rothe (Chicago) SABR Chapter and Co-Chair of the SABR Baseball Cards Research Committee. His collection of Henry Aaron baseball cards and memorabilia is currently on display at the Atlanta History Center, and his baseball card-inspired artwork can be found at PNC Park and the Honus Wagner Museum.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Jim “Mudcat” Grant, Scott Hodges, and Bruce Adelson for their works that sparked an interest in this topic, as well as Mark Armour and Lou Moore for providing early reviews of this paper.

Notes

1. “Tribe Rookie Hoskins Discloses Death Threats,” The Afro-American, February 28, 1953.

2. “2 Negro Players Get Lamesa Baseball Trial,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 20, 1951.

3. “White Texas Loop Team Picks Two Negro Players,” The Call, March 30, 1951.

4. “Pampa Wins in Lamesa,” San Angelo Standard-Times, April 2, 1951.

5. A second catcher, Humberto “Yogi” Marti, was described as a “Cuban Negro rookie” in the various season preview articles that appeared on April 19, 1951. However, subsequent sources suggest Marti was neither Cuban nor Black.

6. “Al Maul’s Bat Leads Winners in Big Attack,” Albuquerque Journal, April 22, 1951.

7. “Lobos Release Cubans, Negro Shortstop Stays,” Clovis News-Journal, April 27, 1951.

8. “Late Lobo Rally Sinks Pioneers,” Clovis News-Journal May 23, 1951.

9. Collier Parris, “Sportometer,” Abilene Reporter-News, May 26, 1951.

10. Burnett may have overestimated the threat posed by the Texans, who went winless (0-7) before being taken over by the league, and then folding. Their final record was 1-11.

11. William B. Ruggles, Texas League Record Book, 1953 Edition (The Texas League of Professional Baseball Clubs, Dallas), 43.

12. “Dallas Okays Use of Negroes in TL,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, January 27, 1952.

13. “Dallas Okays Use of Negroes in TL.”

14. “Dallas Okays Use of Negroes in TL.”

15. “Dallas Okays Use of Negroes in TL.”

16. “Dallas Okays Use of Negroes in TL.”

17. “Dallas Okays Use of Negroes in TL.”

18. “Sports Have No Plans to Use Negroes,” The Times (Shreveport, LA), January 30, 1952.

19. First-day attendance was reported in many sources as 148, however, later reports indicated “nearly 200” or “around 200.” It’s not clear whether these subsequent reports were rounding generously or if they simply accounted for additional players arriving after the first day.

20. “150 Negroes Show For Eagle Tryout,” Corsicana Daily Sun, February 13, 1952; “Eagles Set Tryouts for Negro Players,” Waco Tribune-Herald., February 3, 1952.

21. “Reds Acquire Four Negroes; Tribe Signs 3,” The Tribune (Scranton, PA), February 16, 1952.

22. “1952 Bakersfield Indians,” https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=3080da3d, January 22, 2025.

23. Bruce Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor-League Baseball in the American South (University Press of Virginia, 1999), 54.

24. “Dallas May Sign Negro,” St. Joseph Gazette, March 26, 1952.

25. “May Get Tryouts,” New Pittsburgh Courier, April 14, 1945.

26. John J. Watkins, “Dave Hoskins,” BioProject, Society for American Baseball Research, March 2023.

27. Jim “Mudcat” Grant (with Tom Sabellico and Pat O’Brien), The Black Aces (The Black Aces LLC, 2006), 103.

28. Adelson, 55.

29. “Dallas Ties Bosox,” Pittsburgh Press, April 4, 1952.

30. “Eagles Stop Tulsa by 4-2,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 14, 1952.

31. The Texas League began play in 1888 but missed seasons in 1891, 1893, 1894, 1900, 1901, 1943, 1944, and 1945.

32. Jason A. Schwartz, “August 28, 1952: Dave Hoskins wins 20th game for Dallas Eagles on night held in his honor,” Games Project, Society for American Baseball Research, June 2023, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/august-28-1952-dave-hoskins-wins-20th-game-for-dallas-eagles-on-night-held-in-his-honor/, accessed May 16, 2025.

33. A.S. “Doc” Young, Great Negro Baseball Stars and How They Made the Major Leagues (AS Barnes, New York, 1953), 220; “Dallas Purchases Pair of Pitchers,” Tulsa World, May 18, 1952.

34. “Fort Worth Holds Night for Dave Hoskins,” Jet Magazine, September 11, 1952: 54.

35. “Seeks To Ban Negro-White Sporting Events In State,” Daily World (Opelousas, LA), June 4, 1952; “Tribe Rookie Hoskins Discloses Death Threats,” The Afro-American, February 28, 1953.

36. “Negro Hurler To Make Debut Soon In O.C. Uniform,” Miami News-Record, July 29, 1952.

37. “Greason Defeats Hoskins In Negro Hurling Contest,” Sun Herald, August4, 1952.

38. Schwartz.

39. “Oilers Cop Opener on Stout Varhely’s Arm, Harmon’s Club,” The Tulsa Tribune, April 10, 1953.

40. “Missions Trim Exporters, 6-0,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 11, 1953.

41. “Missions Take Texas Loop Lead,” Tulsa Tribune, April 15, 1953.

42. “Beaumont Exporters Sign K.C. Infielder,” The Call (Kansas City, Missouri), April 23, 1954

43. “Buffs 11, Sports 4,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 28, 1954.

44. “Cats Break Color Line,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 19, 1955.

45. Bill O’Neal, The Texas League (Eakin Press, Austin, Texas, 1987), 123.