The Strange, Extremely Brief Days of Minor League Baseball in Roseville, California

This article was written by Dennis Snelling

This article was published in The National Pastime: Major Research on the Minor Leagues (2022)

On August 4, 1948, the Roseville Press-Tribune trumpeted the arrival of a new professional baseball team. The Far West League’s financially failing Pittsburg Diamonds were moving ninety miles northeast along what was then US Highway 40 to Roseville, just outside Sacramento.1 The late-season move was bold; although Roseville today ranks among California’s fastest growing cities with a population nearing 150,000, a mere eight thousand called Roseville home in 1948.

Among the players headed to the Sacramento suburb was Sal Fucile, Pittsburg’s eighteen-year-old catcher. During Roseville’s brief stint in minor league baseball, Fucile would slam five home runs in a six- game stretch, yet at the end of the year his official record would show zero home runs for the season. Why? Well, it’s not too long a story—and the title of this article provides a clue.

Former big-leaguer Babe Herman suggested to Press-Tribune sports editor Chic Courter that Roseville could have a baseball team. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

To understand the genesis of Roseville’s blink in time as a minor league baseball town, we have to go back one year, to a tryout staged there by the Pittsburgh Pirates in July 1947. The five-day camp for prospective players ages sixteen to twenty-two held the promise of contract offers to the most promising prospects, and featured among its instructors the colorful Babe Herman, a former big-league hitting star who had been Gary Cooper’s stunt double in Pride of the Yankees.2 Two months after the camp, Herman popped into the Press-Tribune office and casually dropped a bomb, asking sports editor Chic Courter, “Do you think a Class D club would go in Roseville?”3

A couple of weeks after that, Cleveland Indians scout Tony Governor arrived in town to evaluate Roseville as a potential site for a farm club.4 Governor addressed the local Lions Club about the possibility, but warned that the high school stadium would be adequate to host a team for only a year, at which point further improvements would have to be made.5 This ignited a debate among local fans, but before any real action could be taken, Roseville lost out to Vallejo, which was willing to commit $25,000 to upgrading its ballpark.6

The lost opportunity roused civic leaders, who met at the Roseville Athletic Club and agreed to formulate a plan for a new baseball plant in time for the 1948 season.7 Art Hadler, who had recently sponsored a team in the Sacramento Winter League, addressed the Roseville Exchange Club and vowed to pursue a Far West League franchise if the city committed to a new stadium8.

In December 1947, there was a glimmer of hope— the Boston Red Sox had secured the league’s final franchise, with the choice of location narrowed to either Oroville or Roseville.9 But Oroville already boasted a finished facility, and at a league meeting held three days before Christmas, Roseville fell short again.10

Eight months later—thanks to Art Hadler’s purchasing Pittsburg’s franchise and fulfilling his earlier promise by relocating the team—Roseville had its chance. The arrival of professional baseball was hailed by the business community as a sign of progress, although a lack of hotels resulted in a plea for residents to open their homes in order to avoid the embarrassment of players being forced to bivouac in the park.11 While Hadler commissioned plans for a more permanent facility, the newly minted Roseville Diamonds took up residence at Roseville High School’s all-dirt playing field, which had been constructed in 1934 as a Works Progress Administration project on land donated by rancher William Kaseberg.12 Local contractor John Piches was hired to expand seating at the facility, which was spruced up as best as could be expected given the four days available for renovations.13 Hadler even rolled up his sleeves and pitched in.14

Despite the venue being considered inferior to the one just vacated, the high school ballpark had its selling points, including outfield dimensions equivalent to other teams in the league and, most important, lighting adequate for night baseball, a vital feature the Pittsburg ballpark had lacked. Hadler, who had accumulated his “fortune” through his Sacramento-based wholesale egg business, hoped to draw fans from the state capital twenty miles to neighboring Placer County, since Sacramento’s Pacific Coast League franchise had become a full-time road team for the remainder of the 1948 season after its home, Edmonds Field, burned to the ground on July 12 in spectacular fashion.15

Chic Courter was unsure whether pro baseball would succeed in Roseville, coming out of the blue as it were. While acknowledging local excitement over the prospect, the Press-Tribune editor alluded to the local tradition of semipro baseball and warned, “It is, at least, like serving English wild boar to people who have been raised on common everyday pork. Maybe they will like it, maybe they won’t.”16

The newly-minted Far West League was attempting to capitalize on a post-war sports boom, minor league baseball having entertained more than forty million spectators in 1947. The circuit was in the first season of its eventual four-year existence and fielded eight teams; Klamath Falls and Medford in Oregon, plus Redding, Willows, Santa Rosa, Oroville, Marysville, and now Roseville, in California. Classified as “D” level, the lowest rung on the baseball ladder, most players were either professional neophytes or marginal talents, although rosters were dotted with interesting names. Future Cy Young Award winner Vernon Law pitched for Santa Rosa, former San Francisco Seals star Ray Perry was player-manager for Redding, and future major league pitching coach and manager Larry Shepard was player-manager for Medford. The father of future Texas Rangers slugger Pete Incaviglia was Medford’s shortstop.

The league’s newest team had actually debuted the previous week with ex-Sacramento Solons outfielder Bill Shewey as manager.17 On July 31, the Roseville Diamonds played their first contest, in Oroville, and lost. Then lost again. They went to Redding and lost three more. Thankfully, the day before arriving at their new home, Roseville swept a doubleheader.18 Nevertheless, the Diamonds were in last place with a record of 33-53, including a 2-5 mark during the first week representing their new city. The team was to play eleven games over the next nine days in Roseville, beginning August 5 against the Santa Rosa Pirates.

Despite Hadler’s boast of his “five thousand dollars per month payroll,” the Diamonds roster was weak— unlike the circuit’s other seven members, they were independent, having no connection to a major league club. A few of Roseville’s players were property of other organizations—overflow from more talented rosters. The remainder were generally those who had failed to catch on elsewhere. One of them, a pitcher, was Hadler’s son, Art Jr. Another was outfielder Vincent DiMaggio—said to be a nineteen-year-old cousin of the famous baseball brothers, not one of them.19

In order to juice local interest, Art Hadler signed popular local semipro star Sammy Piches, a promising infielder who had been released late in spring training by the California League’s Bakersfield Indians, managed by Harry Griswold. Hadler also signed Gene McNulty, whose brother Ray was playing in the Western International League, and whose nephew, Bill McNulty, would star for Sacramento in the minor leagues during the 1970s and appear briefly in the majors.20 Added to the pitching staff were recent Roseville High graduates Jack Hartman and Moe Martin who, like Piches and McNulty, had been playing for the Roseville Athletic Club in the semipro Sacramento County League.

A booster club was formed, with dues of one dollar and the motto, “Win, Lose, or Draw, We’re For the Diamonds.”21 Sammy Piches’s brother John, the contractor who had helped ready the ballpark for game use, was named Boosters president.22

One thousand enthusiastic fans lined up three hours before game time for the Diamonds’ home debut, and they were rewarded with something historic—a no-hitter against their new heroes thrown by Santa Rosa’s Bill LaThorpe. Not only that, LaThorpe allowed only two balls hit out of the infield and struck out seventeen batters—all in the final seven innings—defeating Jack Hartman, who was making his professional debut.23

LaThorpe, a close friend and classmate of Olympic gold medalist Bob Mathias, was no veteran himself, having appeared in his first pro game six weeks earlier after finishing his college season at Fresno State—the win was already LaThorpe’s tenth.24 It was the second time the Diamonds had been no-hit that season; Marysville right-hander Herb Hamilt had done it first when the team was in Pittsburg, an inartistic 14-1 win in which Hamilt walked nine batters and allowed the Diamonds’ only run on a wild pitch that scored a runner from second base.25

The new team’s second home date proved little better than its first, with Roseville scoring six runs while allowing 16 in a game the Diamonds trailed, 9-2, by the bottom of the third inning.26

Roseville finally won its first home contest in five tries, a 12-0 victory in the nightcap of a doubleheader on August 8. But losing quickly resumed, despite catcher Sal Fucile’s home-run streak, encompassing a half-dozen games, all of them defeats. Fucile’s first home run, against the Oroville Red Sox, was controversial—the Red Sox claimed the ball had cleared the fence on a bounce. But when Roseville lost, Oroville dropped the protest and the home run stood.27

Fucile—who had spent spring training with his hometown San Francisco Seals, managed by the legendary Lefty O’Doul—punished Oroville the next day, hitting three home runs in a doubleheader.28 Two of them were off Jules Verne Hudson, arguably the league’s liveliest arm (he struck out 237 batters in 167 innings). Fucile then added another circuit blast to close out the home stand, against Redding.29 These home runs were not the result of friendly home-field dimensions; only one other Diamonds player, Alvin Kruk, hit more than one at the high school ballpark. (He hit two.) Curiously, those five home runs represented Sal Fucile’s entire output for the season in that category, in more than three hundred at bats. It was an unusual power display for a young ballplayer best- known to that point for his spot-on imitations of popular singers.30

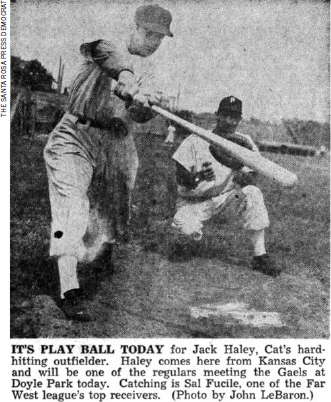

(Santa Rosa Press-Democrat)

As Roseville languished in the Far West League cellar, Art Hadler began looking to the future. He was determined to negotiate a working agreement with the Cleveland Indians or New York Yankees and vowed, “…the fans can look for and expect the kind of a ball club they are entitled to come 1949.”31 Other measures included construction of a new home for the Diamonds on a far corner of the Placer County Fairgrounds, including a grandstand, which Roseville High lacked.32

Unfortunately for Hadler, the 1948 schedule was not yet complete. Complaints multiplied. Beer could not be sold on the high school grounds.33 The local newspaper published only twice a week, hampering promotional efforts. The dirt playing surface was far from ideal, especially when the wind kicked up. Not only that, Hadler had to pay a fine to the league for utilizing a field lacking sod.34

Attendance dropped precipitously after the opener. Even a night saluting Sammy Piches, who had played well as the team’s lead-off hitter and second baseman, failed to check the decline.35 At one point Hadler announced he was going to move a home game to Dixieanne Field in North Sacramento, concerned that competition from the Placer County Fair would prove too stiff.36

After losing to Medford, 5-3, on August 19—exactly two weeks after the team’s debut in Roseville—Art Hadler abandoned the remainder of the home schedule and the Diamonds hit the road for the final three weeks of the season, winning only four of their final twenty-one games.37 One particularly painful loss was to the Medford Dodgers, 15-14, after having led by nine runs in the seventh inning. The winning tally was the result of Roseville’s third baseman protesting a close play and then arguing with the umpire without calling time out. Seeing an opening, the Medford runner took off for home and scored the clinching run while the dispute continued unabated.38

Roseville’s season ended with a six-game sweep at the hands of the Willows Cardinals, leaving the team with a final record of 42-84, including an 11-36 mark as the Roseville Diamonds39. Overall attendance for Pittsburg/Roseville was a league-worst 11,054—less than two hundred per game—and less than one-third that of the Far West League’s top draw, Klamath Falls.40

To add to the indignity, none of the Diamonds’ home games made it into the official record. Apparently the box scores were never forwarded to the league office.41 As a result, there is a notation in the 1949 Sporting News Baseball Guide that twenty games of the Far West League’s 1948 season were not reflected in the final statistics or standings because the official scoresheets were lost.42 Sal Fucile’s impressive home stand is among those missing records. In the nine games he played at Roseville High, Fucile hit two doubles, two triples, and five home runs, compiling a batting average of .382 and a slugging average of 1.000. Meanwhile, his official record shows him with zero home runs in 1948, and zero triples as well. Bob LaThorpe’s no-hitter also went unrecorded.

The only career home run for Sammy Piches, against Redding on August 13, is also missing, and roughly half of his at bats for the Diamonds are not included in his final statistics—games during which he batted a solid .275, on top of the .268 average he carried in the nineteen games which were recorded.43

The Roseville Diamonds did not return in 1949. A plan to combine a War Memorial with a baseball stadium at the fairgrounds collapsed, as some locals did not want a ballpark there and others did not want a memorial.44 No one wanted both.

Hadler first announced he was moving the team to Santa Rosa, that city having lost its franchise. Then, citing health issues, he decided to divest instead.45 He offered the team to groups in both Santa Rosa and Roseburg, Oregon, ultimately selling to the Santa Rosa interests.46 Sal Fucile and Alvin Kruk were the only Roseville players making significant contributions to the team-christened the Santa Rosa Cats—before that franchise folded during the 1949 season.47

Hadler returned to the Far West League in 1950, establishing a new franchise in Eugene, Oregon. He built a ballpark there and operated the team for two seasons until the league went out of business, a victim of the military draft, television’s rapid rise in popularity, and cities ultimately too small to support minor league baseball.48 Hadler ran a supermarket chain in Sacramento before moving an hour away to Grass Valley in 1962, where he operated a newspaper distributorship for nearly two decades prior to his death in 1986, at the age of 85.49

Vincent DiMaggio, whose strong arm—eleven assists in forty-four games as an outfielder in 1948—led to him taking the mound on occasion for Roseville, became a full-time pitcher. Interestingly enough, he faced his namesake in 1949 and 1950 when the more famous Vince DiMaggio became a player-manager in the Far West League for Pittsburg which, after finally agreeing to install lights, had received another team after losing its first to Roseville.

As noted, Sal Fucile stayed with the Roseville franchise when it moved to Santa Rosa, and was considered one of the league’s best prospects. He hit three home runs in 1949, all of which were properly recorded in the official statistics, and was then purchased by the New York Giants, who assigned him to Idaho Falls and then Erie in 1950.50 The Giants tried to send him to Knoxville the next year, but National Guard commitments prevented his leaving California. As a result, Fucile played semipro ball on weekends in San Francisco for the Bartenders Union team.51 He then laced up his spikes for Sioux City in 1952 before being drafted into the Army.52 Stationed at the Presidio in San Francisco, Fucile managed the baseball team there but lost nearly two years of his athletic career.53 Before his days in baseball came to an end, he was briefly a member of the San Francisco Seals in 1954, although he never appeared in a game for them.54 Fucile then followed in his father’s footsteps as a bartender in San Francisco before retiring to Concord, where he died in 2003.55 His family had no knowledge of his playing for Roseville, or his impressive home run streak in August 1948.

Sammy Piches was sent a contract to play for Santa Rosa in 1949, but the military draft intervened and he instead joined the Air Force.56 Later, Art Hadler wanted to bring Piches to Eugene, but by the time of Sammy’s military discharge, the Far West League was defunct. Therefore, Piches’s only (incomplete) record in professional baseball came during his month as the starting second baseman for the Roseville Diamonds. He starred for years with Roseville in the amateur Placer Valley League, remaining one of the city’s most popular athletes. Although he never had children of his own, he never missed his niece’s softball games and usually helped her during warm-ups.57 Like Sal Fucile, he became a popular bartender, working in the family businesses in Roseville, including the Rose Room, before his death in 1999.58

After that two-week sojourn in August 1948, minor league baseball never returned to Roseville. None of the Roseville Diamonds ever made it to the major leagues, and the team was forgotten (until now).

DENNIS SNELLING is a three-time Casey Award finalist, including for The Greatest Minor League and Lefty O’Doul: Baseball’s Forgotten Ambassador. He was a 2015 Seymour Medal Finalist for his biography of Johnny Evers, which was also a Casey finalist. He is recently retired as the Chief Business Official for a school district in Roseville, California, has been a Certified Fraud Examiner since 2005, and is beginning his 49th year as public address announcer for Downey High School in Modesto, proud alma mater of George Lucas and Joe Rudi. He is an active member in both the Lefty O’Doul and Dusty Baker SABR chapters in Northern California.

Notes

1. Roseville Press-Tribune, June 30 and August 4, 1948; Santa Rosa Press-Democrat, June 24, 1948, 6. The old US 40 route now runs along Interstate 80.

2. Roseville Press-Tribune, July 11, 1947, 6. Herman batted .381 and .393 in back-to-back seasons for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Other instructors included former Washington Nationals star Heine Manush—a lifetime .330 batter inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1964—PCL legend Herm Pillette, and Pirates chief scout Ted McGrew, who discovered both Pee Wee Reese and Alvin Dark.

3. Roseville Press-Tribune, September 10, 1947, 10.

4. Roseville Press-Tribune, September 24, 1947, 6.

5. Roseville Press-Tribune, October 1, 1947, 6.

6. Roseville Press-Tribune, October 17, 1947, 6. Vallejo ultimately lost out as well. In order to bring their facility up to standard, land adjacent to the stadium had to be purchased in order to expand, and the parties could not reach agreement. The franchise was then awarded to Pittsburg. (Sacramento Bee, January 9, 1948, 24; Santa Rosa Press-Democrat, February 10, 1948, 10.).

7. Roseville Press-Tribune, October 24, 1947, 1.

8. Roseville Press-Tribune, November 7, 1947, 1.

9. Roseville Press-Tribune, December 3, 1947, 1.

10. Roseville Press-Tribune, December 26, 1947, 1.

11. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 4, 1948, 1.

12. Roseville Press-Tribune, February 28, 1934, 1.

13. Roseville Press-Tribune, July 28, 1948, 1.

14. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 6, 1948, 4 and August 27, 1948, 6.

15. Sacramento Bee, July 12, 1948, 1.

16. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 4, 1948, 6.

17. Santa Rosa Press-Democrat, July 30, 1948, 10.

18. Santa Rosa Press-Democrat, August 5, 1948, 6.

19. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 4, 1948, 6. This Vincent DiMaggio’s middle name was Salvatore, while the more famous Vince DiMaggio had the middle name Paul.

20. Bakersfield Californian, April 9, 1948, 18; Piches, along with another local star, Leo Clark, was originally signed by Governor for Bakersfield and spent spring training there. (Roseville Press-Tribune, November 12, 1947, 6; Bakersfield Californian, February 14, 1948, 11.)

21. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 6, 1948, 4.

22. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 13, 1948, 6. John Piches became a prominent residential developer in Roseville, designed the city’s storm drains, established its first savings and loan, and later founded or led nearly every civic committee in Roseville at one time or another. A city park in Roseville is named in his honor.

23. Santa Rosa Press Democrat, August 6, 1948, 6; Roseville Press-Tribune, August 11, 1948, 6.

24. Fresno Bee, June 19, 1948, 6; Santa Rosa Press Democrat, June 22, 1948, 8. Santa Rosa shortstop Vic Solari went five for five. Two nights later, LaThorpe entered in relief in the ninth inning and struck out the side, giving him twenty strikeouts in an eight-inning stretch against Roseville.

25. Yuba City Independent-Herald, May 6, 1948, 7. Hamilt struck out 11.

26. Santa Rosa Press Democrat, August 7, 1948, 6.

27. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 11, 1948, 6.

28. San Francisco Examiner, March 1, 1948, 22.

29. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 13, 1948, 6.

30. Idaho Post Register, April 26, 1950, 13.

31. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 11, 1948, 6.

32. Roseville Press-Tribune, September 15, 1948, 6.

33. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 25, 1948, 6.

34. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 13, 1948, 6.

35. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 18, 1948, 6.

36. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 18, 1948, 6. The game was ultimately played in Roseville.

37. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 27, 1948, 6.

38. Medford Mail Tribune, August 25, 1948, 6.

39. Minus the missing box scores, Pittsburg/Roseville’s official record is listed as 38-71. (Sporting News Official Baseball Guide, 1949, 408.).

40. The Sporting News, November 10, 1948, 13.

41. Roseville Press-Tribune, September 15, 1948, 6.

42. Sporting News Official Baseball Guide, 1949, 408.

43. Roseville Press-Tribune, August 18, 1948, 6. In the eleven missing home games in which he appeared, Piches collected eleven hits in forty at bats with two doubles, a triple, a home run and three stolen bases.

44. Roseville Press-Tribune, October 20, 1948, 1.

45. Santa Rosa Press Democrat, January 2, 1949, 14; Roseville Press- Tribune, February 23, 1949, 6.

46. Santa Rosa Press Democrat, February 19, 1949, 1.

47. Santa Rosa Press Democrat, August 4, 1949, 1. Santa Rosa folded on August 4 with a record of 43-49, four days after Vallejo went out of business.

48. Eugene Leader, May 11, 1950, 10C, 11C.

49. Sacramento Bee, October 22, 1986, B2.

50. Idaho Post Register, March 21, 1950, 13.

51. San Francisco Examiner, July 3, 1951, 24. Sal’s brother Louis also played for the Bartenders over the years.

52. Knoxville News-Sentinel, April 3, 1951, 17.

53. Correspondence with Nina Fucile, June 27, 2020.

54. San Francisco Examiner, August 11, 1954, 35.

55. San Francisco Chronicle, April 26, 2003, A20.

56. Santa Rosa Press Democrat, February 27, 1949, 1; Roseville Press-Tribune, December 21, 1949, 5.

57. Interview with Patti Kostakis, August 22, 2020.

58. Roseville Press-Tribune, January 24, 1999, A5.