The Struggle to Define ‘Valuable’: Tradition vs. Sabermetrics in the 2012 AL MVP Race

This article was written by Peter Gregg

This article was published in Fall 2017 Baseball Research Journal

This article was selected for inclusion in SABR 50 at 50: The Society for American Baseball Research’s Fifty Most Essential Contributions to the Game.

“When you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind.” — Lord Kelvin

“One absolutely cannot tell, by watching, the difference between a .300 hitter and a .275 hitter. The difference is one hit every two weeks. It might be that a reporter, seeing every game that the team plays, could sense that difference over the course of the year if no records were kept, but I doubt it.” — Bill James, as quoted in “Moneyball”

Today, statistics have become a fundamental component of the fabric of baseball analysis and have gained appreciation at the major-league level.1 As Ron Von Burg and Paul E. Johnson note, “For many, statistics are the main way of understanding and relating to the game of baseball.”2 Broadcasters employ color commentators whose job entails unpacking the nuances of the game, including explicating various statistics and in-game strategies. Fans and media can go to websites like Baseball-Reference.com to see era-by-era comparisons of teams or players and new statistics like WAR (“wins above replacement”) and wRC+ (“weighted runs created plus”).

These newer statistics and data analyses fall under the label “sabermetrics,” defined by Bill James as “the mathematical and statistical study of baseball records” and later broadened to “search for objective knowledge about baseball.”3 Fundamentally, sabermetrics is a search for new ideas in an old game. Nathaniel Stoltz points out, “… as time has progressed and media have diversified, the sabermetric movement has made an increasingly sizeable impact on baseball discourse.”4 Being relatively new, sabermetrics is not steeped in baseball tradition, and this makes it a potential threat to more traditional ways of thinking about the game. Although Michael Lewis’s Moneyball put these advanced analytics into the public’s mind and teams have come to depend on these advanced analytics, sports journalists have been slower to appreciate or incorporate them, generally favoring traditional evaluation methods with which they are comfortable.5,6 Detractors see sabermetrics as a threat to baseball’s past because traditional statistics supposedly embody “intangibles” like heart, grit, and character in celebrating player achievement.7 With the growth of sabermetrics, the traditional terminology employed when using those statistics is undergoing some transformation and causing a bit of upheaval in the process. One of these terms under scrutiny is “valuable” as used in the award for the “most valuable” player.

In Major League Baseball, the “Kenesaw Mountain Landis Memorial Baseball Award” is given by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA) to the “most valuable” player (or “MVP”) in each league, as voted by two organization members from each city. The vote follows consideration by and discourse among member and non-member journalists, bloggers, and fans in and outside the press. In their memo to voters, the BBWAA notes that there is no formal definition of “most valuable” and the meaning is left to the discretion of the voter.8 Because the definition of “value” is the result of discourse and a majority consensus, it is fundamentally determined rhetorically, and as such it is not without debate or controversy.

Statistics are among the key criteria the writers use to determine for whom they should vote and around which the debate revolves in defining the value of the “most valuable” player; consequently, discourse around MVP races tends to focus on performance seen through a statistical lens. For example, in 1941, Joe DiMaggio beat out Ted Williams for MVP largely because of his notable 56-game hit streak despite Williams having a solidly better season.9 In 1999, catcher Pudge Rodriguez beat out pitcher Pedro Martinez in part because some writers felt that a pitcher does not contribute enough to their team to merit “most valuable” because they are not everyday players.10 In 2001, Ichiro Suzuki won the MVP award over Jason Giambi, whose supporters pointed out he led the league in on-base percentage and slugging and beat Ichiro in walks, home runs, and RBIs with 170 fewer at bats.11

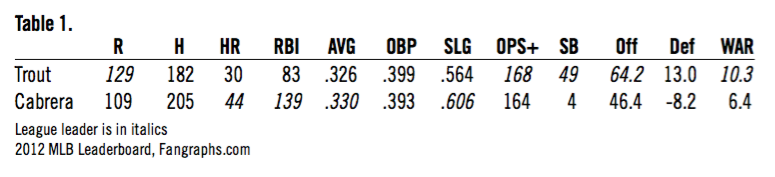

One of the more significantly controversial MVP debates in recent years occurred during the summer and autumn of 2012 on the merits of Miguel Cabrera of the Detroit Tigers and Mike Trout of the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, both of whom were having notable seasons (see Table 1). Cabrera’s supporters pointed out that he was on pace to win the Triple Crown, leading the league in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in, a historic feat that had not happened since 1967. Mike Trout was a rookie sensation; his supporters argued that not only was he running neck-and-neck with Cabrera for batting average and hitting for power, sabermetric analysis showed he was scoring runs and stealing bases at a historic pace, as well as being an exemplary defender.

(Click image to enlarge.)

This noteworthy public crisis between “traditional” and “sabermetric” player evaluation methods formed an important transition point in baseball discourse by the press regarding the use of sabermetrics to evaluate players. “Claims to know are claims of power,”13 and in the case of the 2012 American League Most Valuable Player award, the debate hinged on what knowledge claims constituted the definition of “valuable.” For Joe Posnanski, “… the argument seemed to split baseball fans between those who embrace the new baseball metrics and those who do not.”14 This race served as an important representative anecdote in the ways that sports journalists talked about sabermetrics.15

In this paper, to examine the rhetorical strategies used by reporters to define “valuable,” I apply Edward Schiappa’s methodology for exploring “definitional ruptures.”16 I unpack the factions’ stated purpose or intent of defining, the interests advanced by the definitions, and the consequences of the definition. This three-layer approach reveals that the heart of this tension revolves around the power to define “valuable” as an institutional norm among baseball journalists, with mainstream journalists relying on older statistics and baseball history and newer journalists using sabermetric measures to define “valuable.” I then discuss the consequences of that tension in 2012 and beyond.

I examined published articles and analysis by sports journalists and bloggers starting from late July 2012 and continued through early November after the award was announced. I emphasized writing by BBWAA members and the responses to their articles. The articles constituted the primary discourse since they came from the BBWAA voters or in response to their analysis and argumentation.

Voters in the 2012 AL MVP race who valued the historical rarity of the Triple Crown tipped the scales overwhelmingly in Miguel Cabrera’s favor. (KEITH ALLISON)

METHODS OF ANALYZING DEFINITIONAL RUPTURES

Schiappa notes that the “rhetorical analysis of definition… investigates how people persuade other people to adopt and use certain definitions to the exclusion of others.”17 He argues that definitions are strategies to respond to situations or questions, and they “posit attitudes about situations.”18 Definitions are constituted by “rhetorically induced social knowledge.”19 This social knowledge often comes in the form of authority-based “articulation of what particular words mean and how they should be used to refer to reality.”20 While most definitions are not contested, at times the meaning of a particular word or how it ought to be used is a site of dispute or controversy. The various sides involved in the dispute take on the “natural attitude” that their usage in that specific context is correct.21 For example, a baseball fan who disagrees with an official scorer’s definition of an error has in a small way participated in a definitional dispute; when a team petitions the league for a ruling change on the play, they are arguing over a definition.

These definitional controversies “can be understood, in part, as definitional ruptures.”22 This necessitates not treating definitions as factual claims based on observations about the world and instead treating them as attempts to establish social or institutional norms based on theories of how the world ought to be. Seen in this way, a struggle among journalists to define a term like “valuable” is a struggle for “denotative conformity,” or intersubjective agreement about the meaning of a word.23 Words with high denotative conformity are usually seen as factual observation statements, resulting from their agreed-upon usage and the context of the use. Words with low denotative conformity are usually seen as theory statements about the world. For example, the strike zone has a clear definition in the MLB rulebook, but the strike zone as defined in practice by umpires varies on many different constraints, including the catcher behind the plate.24 Seen in this light, the sides in a definitional rupture in baseball journalism over the meaning of the word “value” use the same word with a different definition and thereby construct or endorse different institutional norms for how it should be used.

Definitions entitle something, giving both a label and a status to that which is defined.25 This entitling places the phenomenon in a set of beliefs or frames about the world that includes what is real and what qualities constitute the phenomenon.26 When a new definition arises in discourse, the interrelated attitudes and beliefs are brought into the debate, and they too must be negotiated. “Whole sets of normative and factual beliefs must be changed before someone may be convinced to accept a new institutional fact.”27 When advocates push for a new definition, they must persuade others to change their linguistic behavior.

Schiappa outlines three major areas for the critic to identify and analyze within a definitional rupture: purpose or intent, use of power, and definitional practice. In exploring purpose or intent, the critic should examine the shared purposes in defining the word, the interests and values advanced by the competing definitions, and the practical consequences of the definition as it affects “the needs and interests of a particular community of language users involved in a dispute.”28 In examining questions of power, the rhetorical critic should identify who has the power to define or speak as an authority and how that power is used within the social institution. “A proposed definition is a request for institutional norms: When should X count as Y in context C?”29 and “[t]he acts of framing and naming always serve preferred interests, even if those interests are not noticed or are uncontroversial.”30 As it pertains to definitional practice, the critic should identify or discover questions within the rupture involving how members do (or do not) achieve denotative conformity with a definition or whether denotative conformity is a reasonable goal.31

SEEING ‘VALUABLE’ AS DEFINITIONAL RUPTURE

The 2012 American League MVP race constituted a crisis among baseball journalists in defining “valuable” as an observation statement (with high denotative conformity) or a theory statement (with low denotative conformity) about the world. Because the BBWAA does not provide a definition for “valuable,” the onus is on the voters themselves to create theory statements to determine it. For traditionalists, value is best defined by an already-recognized significant historical achievement and the success of the team; for sabermetricians, value is defined by stats like WAR, a complex statistical aggregate accounting for the entirety of play. Both factions’ definitions of value included a sensitivity to fairness and egalitarianism. Traditional journalists’ goal was to fairly and equally treat this season’s achievements with the ways past seasons’ achievements had been treated for other players. Sabermetrically-oriented journalists’ goal was to fairly and equally represent all the achievements of players in a season and reward the player who contributed the most. Sean Hartnett contended, “You couldn’t conceive two MVP candidates that provide such conflicting cases for their candidacy… You’ll have old guard writers who will cling to the importance of the Triple Crown and new-age writers who will favor sabermetric measures such as WAR and range factor (RF)—and you’ll never get either side to agree with one another.”32 Ultimately Cabrera won the American League MVP vote, earning twenty-two first place votes over Trout’s six. “After all the debate, all the rhetoric, all the statistical and historical analysis, it wasn’t close.”33

PURPOSE AND INTENT OF DEFINING ‘VALUABLE’

The debate over the definition of “valuable” was an attempt to alter or maintain linguistic behavior. Supporters of both players had the shared purpose of wanting the award to go to the “most valuable” player. In their discourse, they frequently used “valuable” as the key term in determining their vote, and so it was “the term ‘valuable’ that appears to foster differing viewpoints.”34 Numerous other writers noted that the argument was less about statistics versus intangible qualities and more about which statistics should be counted.35 For David Roth “… this vote… was more than just the usual MVP vote. It was also a fairly impassioned contest between two different philosophies and between old-fashioned counting stats and newfangled metrics.”36

Schiappa notes that a definitional rupture “should be addressed in part by re-asking such questions as ‘How should we use the word X?’”37 For Trout supporters, the definition of valuable was driven by the need for statistical accuracy and precision and a search for fairness to other players that year. They generally attempted to quantify his contributions statistically and held a belief in statistical proof as more valid than unmeasurable contributions players might make to a team. Tim Britton suggested, “This is about recognizing Trout’s uniquely comprehensive skill set and the myriad ways he contributed to his team winning baseball games. It’s about appreciating the athletic versatility that baseball, let’s face it, isn’t always known for.”38

For the supporters of Cabrera, the definition of valuable consisted of the player making significant contributions to a team that made the playoffs and one that included historically important statistical achievements as meriting the award, regardless of other measures of value. Bill Madden summarized the position:

Here’s a guy having one of the greatest offensive seasons in history, on the cusp of being the first Triple Crown winner since Carl Yastrzemski in 1967, and yet there is this clamor from the sabermetrics gallery that Cabrera must be penalized for his slowness afoot and supposed defensive shortcomings. To hear them tell it, if Cabrera winds up leading the league in batting, homers, RBI, slugging and total bases, and being second in hits and runs, it will still pale in comparison to L.A. Angels super rookie Mike Trout leading the league in runs, stolen bases and… WAR.39

Traditional sports journalists tended to emphasize baseball history and significant achievement in their definition of “value.” Cabrera’s Triple Crown played a decisive role in their votes for him. “The MVP is the Big Dog of individual awards in sports. It often serves as a Hall of Fame deal-breaker. Yet the word ‘valuable’ restricts it to those whose brilliance made a difference, even though the electors are specifically told that it really isn’t tied to team performance. They decide their own criteria.”40 The fact that Cabrera played better in the last months of the season and the Tigers made the playoffs also contributed to his case for most valuable player. “We more ‘traditional’ baseball journalists do tend to weigh postseason appearances highly when it comes to the MVP because, really, what else is value for? Cabrera got his team to the playoffs. Trout did not.”41 Other Cabrera voters felt this was an opportunity to support Cabrera as the exemplar of valuable production. “If Cabrera wins the MVP it will repudiate nothing Trout did. It will simply be a … reaffirmation of value.”42 For Mark Feinsand, there was a distinction between best player and most valuable player. “I think Trout was the best overall player in the game this season, especially when you factor in his defense and baserunning. But that doesn’t mean I thought he was the most valuable.”43

The idea of fairness and equal treatment in a single season is partially what drove the Trout supporters to WAR as a key statistic in measuring value. “Baseball experts have spent decades trying to find a way to quantify all of a player’s contributions and boil it down into one number. The best measurement we have right now is what’s known as Wins Above Replacement (WAR).”44 Traditional baseball statistics tend to be “counting” statistics, where an event is tallied: a batted ball leaves the field of play in fair territory without hitting the ground and is counted as a home run, the batter hits the ball in fair territory and reaches base safely without a fielding error and it is counted as a hit, and so forth. More complex statistics are derived from averages: average hits per at bat yields a “batting average,” average of earned runs per nine innings equals “earned run average.” Almost all are easily seen, tallied, and understood.

Advanced baseball statistics tend to be derived from more complex formulae. In the case of WAR for position players, the final number is the product of various measures including hitting, baserunning, and defense, some of which rely on other advanced statistics, and then that statistical value is normalized against the standard performance in that season. This formula allows the player to be compared against his peers and in a manner that includes the complex ways the player contributes that may not be easily tallied and seen. For Carl Bialik, “Wins above replacement [is] an imperfect stat that still does a better job than any other of encapsulating a player’s overall on-field value,”45 and for Neil Paine WAR is “the single-number metric of choice for most sabermetricians when it comes to measuring a player’s all-around value.”46

For sabermetricians in 2012, Trout clearly created the most value as a player. “Basically WAR—and some other advanced metrics—showed that whatever advantages Cabrera had in terms of power and batting average and timely hitting were swamped by Trout’s advantages as a fielder, base runner and player who gets on base. The argument made sense to many of us who champion the advanced statistics and their power to get closer to a player’s true value.”47 Journalists supporting Trout’s case noted that not only did he lead the league in WAR, but he did so in a historically significant way. “Trout’s is the clearest case in 99 years as the majors’ MVP… That’s just how much better he’s been than his peers.”48 Writers also addressed some “intangible” or non-quantifiable factors often used by Cabrera supporters, as Mark Reynolds wrote at Bleacher Report:

As long as you think the MVP award should go the player who produced the most value, then Trout should have been the winner because Cabrera’s offense was not superior enough to make up for the difference in the other categories. Cabrera might have been great in the locker room, but there’s no evidence that Trout wasn’t a great teammate, too. Cabrera’s team made the postseason, but Trout’s team won more games.49

Many writers argued that the Triple Crown is overvalued. Zachary D. Rhymer notes that “the Triple Crown indeed is a relic. It’s a novel accomplishment, but things have changed too much over the last half century for both writers and baseball fans to still believe that the Triple Crown is the ultimate measure of value.”50 For sabermetricians each leg of the Triple Crown represents older, less helpful statistics for evaluating player performance. The RBI (or “runs batted in”) depends considerably on the quality of a hitter’s teammates, because they need to be on base for the batter to drive them in for runs. The home run shows power potential but is also dependent on factors like the depth of the outfields where the batter hits; since a team plays half its games at home, some batters are fortunate to play half their games on a field that is favorable to hitting home runs. Batting average is a fine descriptor of how often the batter reaches base safely on a hit, but does not capture the ability of the batter to reach base without getting out or to reach base with a double or triple. For many sabermetricians, the preferred statistic is either on-base percentage (OBP) or on-base plus slugging average (or “OPS”).

Mike Trout’s 2012 performance was emblematic for sabermetricians struggling for acceptance of sophisticated player valuation. (IAN D’ANDREA)

USE OF POWER

Craig Calcaterra thought that the “MVP award voting, at least in the American League, has taken on political and philosophical overtones.”51 Supporters of both players claimed to know what “valuable” meant within their individual set of criteria. Because the result comes via vote of two members from each American League city, the power to define ultimately resided in those (then) 28 members. Non-voting members and non-members could rally for particular perspectives on what they would or what members should do, but they did not actually vote. The debate over value continued the tension between traditional sports journalists and an emerging group interested in newer ways of evaluating players and making strategic choices. An overwhelming majority of established writers voted for Cabrera. “The Triple Crown winner’s main constituency was old people in old media. Twenty-four of the MVP voters work for newspapers or newspaper groups; 21 of them (88 percent) voted for Cabrera… every voter 51 and above… sided with Cabrera, the old-guard candidate.”52

Because the BBWAA nominates each season’s voters, it is feasible that the balance of power in the organization will shift as one faction or the other jostles for power over the seasons, and so the stakes for a given debate should be seen as a part of a longer-term power struggle. The tension over Trout and Cabrera for Most Valuable Player was a struggle for authority in the press. It was a question over the type of knowledge needed to be regarded as a baseball expert. “The false Trout/Cabrera debate, stripped of Tigers and Angels fans, is just the latest in the ongoing battle between two camps in the baseball media, one of which has seen its longtime primacy usurped by new writers, mostly younger, who look at the game in different ways and have more in common with successful front offices.”53 Established writers saw sabermetricians as using advanced statistics to usurp their power and prestige. Sabermetricians saw established writers using traditional tools to support Cabrera and undermine the utility of sabermetric evaluation.

One technique used by traditionally-oriented journalists to subordinate the sabermetrically-oriented writers was to resort to name-calling. “The old-school columnists often trafficked in ignorance and name-calling—relying on the cliché that the statistical community consisted entirely of geeks still living in their mothers’ basements.”54 This cliché is epitomized by Mitch Albom’s claim:

[Baseball] is simply being saturated with situational statistics. What other sport keeps coming up with new categories to watch the same game? A box score now reads like an annual report. And this WAR statistic—which measures the number of wins a player gives his team versus a replacement player of minor league/bench talent (honestly, who comes up with this stuff?)—is another way of declaring, “Nerds win!”55

Commonly the tone was aggressive and characterized sabermetricians as effete and weak, a position in alignment with Michael L. Butterworth’s findings regarding the treatment of statistical political and sports discourse.56 In addition to calling sabermetricans “geeks,” Madden worried advanced analytics is “turning baseball into an inhuman board game.”57

The pro-Cabrera writers used their definition to defer to historical tradition and significance. For them, the power to decide the meaning of “value” should rest in the hands of the people who have always decided it, not up-and-coming sabermetrician journalists. For the traditionalists, WAR is seen as a statistic “for geeks who don’t know baseball… the real argument that non-Tigers fans are making about Trout.”58 For sabermetricians, the 2012 MVP race was a way to add clarity to the ways people think about player value. In his discussion of the race, Jonah Keri argued that Cabrera won because a player’s value is perceived by its cultural and financial incentives.59 Players who hit home runs and drive in RBIs get emphasized more in the press, get more praise by their teammates, and get larger contracts, and as a result they are more likely to win the Most Valuable Player award, although Nate Silver noted that “the real progress in the statistical analysis of baseball is in the ability to evaluate the contributions that a player makes on the field in a more reliable and comprehensive way.”60

DEFINITIONAL PRACTICE

The MVP debate arose from a lack of denotative conformity and was an attempt to attain intersubjective agreement. Unlike many definitional disputes, the MVP award is the product of a vote in which scoring reflects amajority preference. The Trout-Cabrera debate represented the changes in the makeup of the BBWAA. “There is most definitely a growing divide among the BBWAA and the plethora of talented writers online who either are not members of the BBWAA or members that get drowned out by their older cohorts in the association.”61 Ultimately, the definition used is the one that serves the preferred or powerful interests, since those members have the power to entitle the word with specific meaning and weight. The preferred interests establish the social or institutional norms. The Trout-Cabrera MVP vote re-entitled “value” with the traditional definition: the player with the most value is the one who makes historically significant contributions on a playoff team.

While the vote did not necessarily stop the discourse or guarantee denotative conformity, it offers a resolution to that specific definitional rupture. Josh Levin suggested, “The BBWAA’s voting system empowers baseball’s most-conservative voices and disenfranchises those with non-prehistoric views.”62 John Shipley was more optimistic, noting “Maybe someday WAR, BABIP (Batting Average on Balls in Play) and RC27 (Runs Created per 27 outs) will replace the old stats as the new standards. But for those who came up memorizing batting averages and RBI totals from the backs of baseball cards, they’re still relegated to the fringes of the national pastime.”63

Entitling “value” as sabermetrically-defined would give power to the individuals with the expertise, knowledge, and background to understand, analyze, and discuss it. This community is largely a newer, younger generation of writers struggling for power within sports journalism. Matthew Trueblood suggested that the 2012 MVP race was one of the last gasps of power by the old guard of baseball writers, noting that “Soon, the electorate for these awards will be overwhelmingly new-school.”64 Calcaterra argued that this struggle to determine which measures should be used to gauge the value of a player exemplify a struggle over the political economy of baseball discourse.65 The established writers defended their power to determine who should win based on the criteria they chose, and they entitled and endorsed their particular definition as best they could because their jobs were disappearing and they were losing their place as authorities in the game. The new guard of sports writers were “defensive and insecure about being taken seriously as baseball authorities”66 and treated as “second-class citizens”67 among baseball journalists, an ironic position since baseball front offices have recognized the value of advanced analytics and have their own proprietary set of sabermetric statistics, putting team management on a more similar ground with newer writers than the established sports journalists.

Baseball front offices believe in statistics as the key way to evaluate players. Team officials know the value of defense and base-running and have proprietary ways of evaluating players statistically. Traditional writers and players consequently do not have the best tools to gauge the quality of a player, and Trout would almost certainly have the support of front offices but not many writers and players.68 In recognizing the change of power in the BBWAA, Levin noted that “Eventually, reason will win out over superstition, the conventional wisdom will change, and the nerds will become the establishment. The voters of 2012 will not decide who wins the MVP in 2032, and for that we can all be thankful.”69 Two seasons later when Trout finally beat Cabrera for MVP after losing to him two seasons in a row, Paine noted, “In what’s quickly becoming an annual rite of summer, Mike Trout of the Los Angeles Angels once again led the American League in wins above replacement (WAR), the single-number metric of choice for most sabermetricians when it comes to measuring a player’s all-around value.”70 Perhaps the tide finally turned for sabermetrician journalists.

AFTERMATH OF THE DEFINITIONAL RUPTURE

The Trout-Cabrera debate of 2012 was an attempt to reinforce or change institutional norms within baseball journalism, addressing the question of how player value should be defined in practice: How should we use “valuable” in determining the most valuable player? However, baseball is slow to change, and “The statistical revolution that’s permeating the baseball world hasn’t won widespread acceptance just yet.”71 Looking back at the race, Carrie Kreiswirth interviewed ESPN editor Scott Burton, who noted, “In following the MVP debate between Mike Trout and Miguel Cabrera, it was shocking to me to witness the backlash to the analytics argument in favor of Trout. It was like we were stuck in 1998. And the fact that Trout lost handily, despite being superior in almost every meaningful way to Cabrera—as encapsulated by WAR—represented a failure for the analytics community. We lost the fight, badly.”72

As sabermetric discourse grows in media and front offices, it will change how writers and fans talk about and understand baseball. Any substantial shift in baseball discourse is important for the sport, a game grounded in history and tradition. In the time since Trout-Cabrera, the use of sabermetric analysis by commentators, analysts, managers, and players has increased considerably. Today, we find discussions of WAR happening during broadcasts, fans are more comfortable with advanced analytics, and sabermetricians are gaining even more control in baseball front offices.73

The rise in the use of the defensive shift, more attention to things like pitch framing by catchers and batting average on balls in play, and other new approaches to player evaluation and scouting all show greater sensitivity to sabermetric reasoning and optimizing choices, and show its increased persuasiveness on people who think about and play baseball.74 Sabermetrics has a louder voice in baseball discourse, but there is also a risk in seeing statistics as the only way to “truth” in valuing (and evaluating) players. There is the possibility that a faith in traditional value is being replaced with a faith in statistical value, a shift from more qualitative and visual evaluation to more quantitative and abstract reasoning. Seeing baseball as a series of statistical events and choices that can and should be statistically optimized runs the risk of making baseball even more neo-liberal and governed by economic metaphors.

There also remains the possibility that with specialized discourse “that the manner in which we draw distinctions among the different spheres may, itself, contribute to the decline of public discourse.”75 As baseball becomes more advanced statistically, we may be seeing the shifting of the permitted “speakers” moving from practitioners and lay observers to experts in elevated theory or statistics. With that shift may come alienation between traditional fans and sabermetrically-oriented ones. For example, acronyms can function in the bureaucratization of a field, alienating the laity from the bureaucratic experts and thereby entrenching the experts’ power in the field. We see this concern expressed in Albom’s infamous tirade against sabermetricians’ support of Trout: “There is no end to the appetite for categories—from OBP to OPS to WAR. I mean, OMG! The number of triples hit while wearing a certain-colored underwear is probably being measured as we speak.”76 While it is easy to write off Albom’s ridicule as satire or sarcasm, his article also expresses a concern at the overvaluation of complex statistics and obfuscation by new acronyms over the practical or observational qualities of player evaluation and the potential alienation that results.

Baseball as an institution continues to be somewhat slower than individual teams and writers to accept the statistical revolution played out on the fields. For example, in 2015 after the heavy use of unconventional, sabermetrically-inspired defensive shifts depressed offensive statistics, MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred said he was open to banning particular types of those shifts because of their negative effect and their deviation from traditional defensive arrangement.77 This move received considerable pushback from the press, something that pre-2012 seemed rather unlikely in two ways: these kinds of defensive shifts were significantly less common, and the press likely would treat this as a negative instance of sabermetrics intruding on baseball in a clear, practical way that should not be permitted.

CONCLUSION

This project explores a representative anecdote of where and how definitions matter, and it shows the flexibility of Schiappa’s method in exploring definitional practice.78 It does not claim to be the last word on the matter. Since this is a single example based on a brief snapshot of time, future research in tension between sabermetrics and “traditional” baseball could look at changing definitional practice longer term, gravitating toward different crises or debates: Felix Hernandez and pitcher wins used in determining the Cy Young Award, how the RBI has been valued over time, the case for Jack Morris and the Hall of Fame. This project could also be seen as a first step in the larger fusing of rhetorical criticism and sports statistics, a move toward exploring the rhetoric of sabermetrics: the ways that baseball statisticians use words to define reality.

DR. PETER B. GREGG, PhD is an assistant professor of Communication and Journalism at the University of St. Thomas. His research interests include media history, production, and audiences. His co-authored work “The Parasocial Contact Hypothesis” won the National Communication Association’s 2017 Charles H. Woolbert Research Award. He is a lifelong Detroit Tigers fan.

Notes

1 Alan Schwarz, The Numbers Game: Baseball’s Lifelong Fascination With Statistics. (New York, NY: Thomas Dunne, 2004)

2 Ron Von Burg and Paul E. Johnson, “Yearning for a Past That Never Was: Baseball, Steroids, and the Anxiety of the American Dream,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 26(4): 356.

3 Bill James, 1980 Baseball Abstract. (Lawrence, KS: Self-published, 1980).

4 Nathaniel H. Stoltz, “Sabermetrics over time: Persuasion and symbolic convergence across a diffusion of innovations” (Master’s thesis, Wake Forest University, 2014), accessed September 19, 2015, https://wakespace.lib.wfu.edu/bitstream/handle/10339/39317/Stoltz_wfu_0248M_10600.pdf, 5.

5 Michael Lewis, Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game. (New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 2003).

6 Travis Sawchik, Big Data Baseball: Math, Miracles, and the End of a 20-Year Losing Streak. (New York, NY: Flatiron Books, 2015). Ben Lindbergh & Sam Miller, The Only Rule Is It Has to Work: Our Wild Experiment Building a New Kind of Baseball Team. (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 2016). Brian Kenny, Ahead of the Curve: Inside the Baseball Revolution. (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2016).

7 Lonnie Wheeler, Intangiball: the Subtle Things That Win Baseball Games. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015).

8 “Voting FAQ,” Baseball Writers’ Association of America, accessed November 2, 2016, http://bbwaa.com/voting-faq.

9 “Baseball’s Most Controversial MVP Winners,” Real Clear Sports, May 17, 2013, accessed November 2, 2016, http://www.realclearsports.com/lists/top_10_controversial_mvp_winners/

10 “Rodriguez Wins AL MVP Award,” Los Angeles Times, November 19, 1999, accessed November 2, 2016, http://articles.latimes.com/1999/nov/19/sports/sp-35454.

11 Arad Markowitz, “MLB: Top 10 Most Undeserving MVPs of All Time,” Bleacher Report, May 26, 2011, accessed November 2, 2016, http://bleacherreport.com/articles/713962-mlb-top-10-most-undeserving-mvps-of-all-time/page/8

12 “2012 Major League Leaderboards.” Fangraphs.com. Accessed August 28, 2017. http://www.fangraphs.com/leaders.aspx?pos=all&stats=bat&lg=all&qual=y&type=1&season=2012&month=0&season1=2012&ind=0&team=0&rost=0&age=0&filter=&players=0

13 Edward Schiappa, “’Spheres of Argument’ as Topoi for the Critical Study of Power/Knowledge,” in Spheres of argument, Bruce E Gronbeck ed. (Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association, 1989), 48.

14 Joe Posnanski, “Revisiting Trout vs. Cabrera MVP Debate – With a Twist,” NBCSports.com, March 4, 2013, 6. Accessed December 15, 2015. http://mlb.nbcsports.com/2013/03/04/revisiting-trout-vs-cabrera-mvp-debate-with-a-twist/

15 Kenneth Burke, A Grammar of Motives. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969).

16 Edward Schiappa, Defining Reality: Definitions and the Politics of Meaning. (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003), 7.

17 Schiappa, Defining Reality, 4.

18 James W. Chesebro, “Definition as Rhetorical Strategy,” Pennsylvania Speech Communication Annual 41 (1985), 10.

19 Schiappa, Defining Reality, 3.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid., 7.

22 Ibid., 10.

23 Ibid., 46.

24 Mike Fast, “Spinning Yarn: Removing the Mask Encore Presentation,” Baseball Prospectus, September 24, 2011. Accessed September 19, 2015, http://www.baseballprospectus.com/article.php?articleid=15093. Scott Lindholm, “How Well Do Umpires Call Balls and Strikes?” Beyond the Box Score, January 27. 2014. Accessed December 6, 2015, http://www.beyondtheboxscore.com/2014/1/27/5341676/how-well-do-umpires-call-balls-and-strikes.

25 Burke, Grammar of Motives, 359-379

26 Schiappa, Defining Reality, 116

27 Schiappa, Defining Reality, 66

28 Ibid., 178

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid., 154

31 Ibid., 179

32 Sean Hartnett, “Cabrera vs. Trout – Sorting Through the Great 2012 AL MVP Debate,” CBS New York, October 4, 2012, 4. Accessed December 9, 2015, http://newyork.cbslocal.com/2012/10/04/hartnett-cabrera-vs-trout-sorting-through-the-great-2012-al-mvp-debate/.

33 Jason Beck, “Miggy Beats Trout to Add AL MVP to Collection,”MLB.com, November 15. 2012, 1. Accessed December 9, 2015, http://m.mlb.com/news/article/40301568/.

34 Alden Gonzalez, “Definition of Most Valuable? MVP Voters Explain,” Angels.com, November 15, 2013, 18. Accessed November 2, 2016, http://wap.mlb.com/laa/news/article/2013111563941740/?locale=es_CO

35 See John Shipley, J. (2012, September 20). “MVP Numbers: Old School (Miguel Cabrera) vs. New Age (Mike Trout),” St. Paul Pioneer Press, September 20, 2012. Accessed December 9, 2015, http://www.twincities.com/ci_21603755/mvp–‐numbers–‐old–‐school–‐miguel–‐caberera–‐vs–‐new; Nate Silver, “The Statistical Case Against Cabrera for MVP,” New York Times, November 14, 2012. Accessed November 2, 2016, https://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/14/the-statistical-case-against-cabrera-for-m-v-p/?mcubz=1&_r=0; Jonah Keri, “Mike Trout is the Real MVP, Miguel Cabrera is the Players’ MVP,” Grantland, November 16, 2012. Accessed December 9, 2015, http://grantland.com/the-triangle/mike-trout-is-the-mvp-cabrera-is-the-players-mvp/?print=1.

36 David Roth, “Revenge Against Baseball’s Nerds,” Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2016, http://blogs.wsj.com/dailyfix/2012/11/16/revenge-against-baseballs-nerds, paragraph 3.

37 Schiappa, Defining Reality, 89

38 Tim Britton, “Why I Voted for Mike Trout,” Providence Journal, November 15, 2012. Accessed September 16, 205, http://www.providencejournal.com/article/20121115/SPORTS/311159990, paragraph 15.

39 Bill Madden, “SABR Geeks Sabotaging Cy and MVP Races,” New York Daily News, September 29, 2012. Accessed July 20, 2016, http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/sabr-geeks-stiff-dickey-miguel-cabrera-nl-cy-young-al-mvp-voting-means-war-article-1.1171008, paragraph 6. Ellipsis in original.

40 Mark Whicker, “Cabrera Over Trout for MVP is the Right Call,” Orange County Register, November 13, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2016, http://www.ocregister.com/2012/11/13/whicker-cabrera-over-trout-for-mvp-is-the-right-call/, paragraphs 8-10.

41 Susan Slusser, “Why I Voted for Miguel Cabrera,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 15, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2016, http://blog.sfgate.com/athletics/2012/11/15/why-i-voted-for-miguel-cabrera/, paragraph 4.

42 Whicker, “Right Call,” 34. Ellipsis added.

43 Mark Feinsand, “Miguel, Not Trout, Hooks My MVP Vote,” New York Daily News, November 16, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2016, http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/feinsand-miguel-not-trout-hooks-mvp-vote-article-1.1202954, paragraph 4.

44 Steve Gardner, “Trout Deserved Better in MVP Voting,” USA Today, November 16, 2012. Accessed July 19, 2016, https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/2012/11/15/mike-trout-mvp-case/1707791/, paragraph 17.

45 Carl Bialik, “The MVP Case for Mike Trout,” Wall Street Journal, September 24, 2012. Accessed December 9, 2015, http://blogs.wsj.com/dailyfix/2012/09/24/the-mvp-case-for-mike-trout-vs-miguel-cabrera/tab/print, paragraph 3.

46 Neil Paine, “Finally, Mike Trout is the MVP,” FiveThirtyEight, November 14, 2014. Accessed December 9, 2015, https://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/finally-mike-trout-is-the-mvp/, paragraph 1.

47 Posnanski, “Revisiting Trout,” paragraph 8.

48 Bialik, “MVP Case,” paragraph 4.

49 Mark Reynolds, “Mike Trout vs. Miguel Cabrera: Revisiting the 2012 American League MVP Race,” Bleacher Report, March 17, 2013. Accessed December 9, 2015, http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1570961-mike-trout-vs-miguel-cabrera-revisiting-the-2012-american-league-mvp-race, paragraph 24.

50 Zachary D. Rhymer, “AL MVP Award 2012 Voting Results: Why Mike Trout Got Totally Screwed,” Bleacher Report, November 15, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2016, http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1410684-al-mvp-award-2012-voting-results-why-mike-trout-got-totally-screwed, paragraph 14.

51 Craig Calcaterra, “Mike Trout vs. Miguel Cabrera a Proxy Battle in a Larger Cold War,” NBCSports.com, November 15, 2013. Accessed June 16, 2016, http://mlb.nbcsports.com/2013/11/15/miketrout-vs-miguel-cabrera-a-proxy-battle-in-alarger-cold-war, paragraph 6.

52 Josh Levin, “Miguel Cabrera is Mitt Romney,” Slate, November 16, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2016, http://www.slate.com/articles/sports/sports_nut/2012/11/miguel_cabrera_is_mitt_romney_this_time_the_candidate_of_old_white_men_won.html, paragraph 14.

53 Keith Law, “Trout the Rational Choice for AL MVP,” ESPN.com, September 25, 2012. Accessed July 21, 2016, http://www.espn.com/blog/keith-law/insider/post?id=155, paragraph 22.

54 Reynolds, “Revisiting,” paragraph 8.

55 Mitch Albom, “Miguel Cabrera’s Award a Win for Fans, Defeat for Stats Geeks,” Detroit Free Press, November 16, 2012. Accessed December 9, 2015, http://www.freep.com/article/20121116/COL01/311160108, paragraph 25.

56 Michael L. Butterworth, “Nate Silver and Campaign 2012: Sport, the Statistical Frame, and the Rhetoric of Electoral Forecasting,” Journal of Communication 64 (2012), 895-914.

57 Madden, “SABR Geeks,” paragraph 6.

58 Law, “Rational Choice,” paragraph 20.

59 Keri, “Trout Real MVP.”

60 Silver, “Statistical Case Against Cabrera,” paragraph 26

61 Joe Lucia, “AL MVP voting causes baseball writers to go nuclear,” Awful Announcing, November 16, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2016, http://awfulannouncing.com/2012-articles/al-mvp-voting-causes-baseball-writers-to-go-nuclear.html, paragraph 7.

62 Levin, “Cabrera is Romney,” paragraph 16.

63 Shipley, “MVP Numbers,” paragraph 20.

64 Matthew Trueblood, “Good for baseball: Miguel Cabrera won the 2012 AL MVP over Mike Trout,” Banished to the Pen, November 16, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2016, http://www.banishedtothepen.com/good-for-baseball-miguel-cabrera-won-the-2012-al-mvp-over-mike-trout, paragraph 9.

65 Calcaterra, “Proxy Battle.”

66 Ibid., paragraph 14.

67 Ibid., paragraph 15.

68 Buster Olney, “Framing the American League MVP debate,” ESPN.com, September 19, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2016 http://www.espn.com/blog/buster-olney/insider/post?id=58.

69 Levin, “Cabrera is Romney,” paragraph 17.

70 Paine, “Finally Mike Trout,” paragraph 1.

71 Gardner, “Trout Deserved Better,” paragraph 1.

72 Carrie Kreiswirth, “ESPN The Mag’s ‘The Analytics Issue’ dissects debate,” ESPNFrontRow.com, February 2013. Accessed December 9, 2015, http://www.espnfrontrow.com/2013/02/espn-the-mags-the-analytics-issue-dissects-the-miguel-cabrera-vs-mike-trout-al-mvp-debate, paragraph 5.

73 Stoltz, “Sabermetrics Over Time.”

74 Sawchik, Big Data Baseball.

75 Schiappa, “Spheres of Argument,” 48.

76 Albom, “Stat Geeks,” paragraph 8.

77 Cliff Corcoran, “New Commissioner Rob Manfred’s Talk of Banning Shifts Makes No Sense,” Sports Illustrated, January 26, 2015. Accessed July 28, 2016, http://www.si.com/mlb/2015/01/26/rob-manfred-defensive-shifts-mlb-commissioner.

78 Schiappa, Defining Reality.