The Summer of ’14: Almost a Miracle: The Cardinals’ First Great Pennant Race

This article was written by Steve Steinberg

This article was published in 2007 Baseball Research Journal

“St. Louis is one of the greatest baseball towns in the country. It has probably turned out more professional baseball players than any other city. … The youngsters of St. Louis know more about big league baseball than the adult fans of the average city.” – Damon Runyon

August 26, 1914, was an improbable day in a turbulent season in a city that had not experienced a pennant since 1888. The St. Louis Cardinals had surged toward the top of the National League and were playing for first place today. Twenty seven thousand fans had streamed into Robison Field, a ballpark with a seating capacity of not much more than 20,000. Thousands crammed into the aisles, and thousands more spilled onto the field, roped off in the outfield and even behind home plate.

The world seemed askew, providing an eerie backdrop for the national pastime. Europe was sinking into war, as the flames of conflict in the Balkans were engulfing the continent. In Rome, another group of cardinals had gathered, to select a new leader after the death of Pope Pius X a few days earlier. National League baseball was turned upside-down, with the perennially weak Cardinals of St. Louis and Braves of Boston challenging the New York Giants, winners of the past three National League pennants. The thrilling pennant race provided fans with relief from the bleak and unsettling news coming across the ocean.

“Woman’s presence at the games will have a civilizing effect.” – St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 9, 1911

Helene Britton was the first female owner of a major league sports team in America. The Cardinals had been owned by her father and uncle, Frank and Stanley Robison. Frank died in 1908, and her uncle— who never married—passed away in the spring of 1911. Her father had no sons, and thus did a woman enter that exclusive male bastion called organized ball. What’s more, she was later described as a “militant suffragette.” She brought an exciting new element into owners’ meetings, and not simply with her colorful attire. The press soon dubbed the attractive 32-year-old mother of two, “Lady Bee.”

Helene Britton was no stranger to baseball; she grew up in a baseball family. As a youngster, she played ball, learned to keep score, and even served as a mascot for the Cleveland Spiders, another team that her father and uncle owned.

Starting that spring of 1911, the new owner of the Cardinals built up Ladies’ Day before it was popular. She made a ban on booze at the ballpark permanent. She also experienced something her father and uncle had not known for more than a decade: a season that was a box office and financial success. The Cardinals flirted with first place for three months before fading to fifth. Attendance rose to 447,000 that year, more than 120,000 over the previous year and by far the most the team ever drew to that point.

HER SIGNATURE MOVE

The Cardinals returned to their losing ways in 1912, finishing in sixth place with a 63-90 record. Shortly after the season’s end, Lady Bee exercised the ultimate prerogative of ownership when she fired the team’s colorful and temperamental manager, Roger Bresnahan. He had difficulty accepting a female boss from the start and didn’t take kindly to her baseball suggestions, which increased as the losses piled up. At the same time, the all-too-familiar financial pressures returned to the Cardinals. Attendance plummeted almost 50% from 1911, and Britton had large legal bills from settling her uncle’s estate.

Lady Bee made the surprise choice of Cardinals second baseman Miller Huggins as the team’s new skipper. Perhaps it was not a total surprise, since she had vetoed a trade Bresnahan had put together earlier that year, one that would have sent Huggins to Cincinnati.

The disappointing 1912 season was followed by a disastrous one in 1913 (51-99). Huggins’ first season as a manager was almost his last. Rumors swirled about his imminent firing or resignation. The losses led to the almost inevitable dissension that simmers during a disappointing campaign. Somehow Huggins hung in there, and the Brittons (Helene and her husband, Schuyler) stuck with him.

HIS SIGNATURE MOVE

“I simply had to set my house in order, so as to get real cooperation. The change in the spirit and morale of the team was immediately noticeable.” – Miller Huggins, syndicated column, February 27, 1924

Miller Huggins was talking about his first big trade as manager, a multi-player deal that sent the Cardinals’ one bona fide star, first baseman Ed Konetchy, to Pittsburgh in December 1913. Most baseball observers felt that the Pirates had gotten the better of the deal. For the Cards’ skipper, it was a trade that had to be made—to establish himself as the team’s leader and to rid the squad of an imposing center of unrest. The unhappy Konetchy increasingly had felt that he, not Huggins, should be the skipper.

THE OTHER 1914 WAR

“The Feds are welcomed in St. Louis because the fans have grown tired of tail-end baseball.” – Sid Keener, St. Louis Times, March 31, 1914

Baseball in 1914 dawned with three teams in St. Louis: the Cardinals, the American League’s Browns, and the Terriers of the upstart Federal League. For the first time since the rise of the American League in 1901-1902, players had an alternative to playing for the team that controlled them for their entire career, under what was known as the “reserve clause.” The Federal League was actively raiding the established leagues for players, and salaries skyrocketed.

To make the Terriers more appealing to St. Louis fans, their cantankerous owner, Phil Ball, appointed legendary Chicago Cubs’ pitcher Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown as their player-manager. Ironically, Brown had been a St. Louis Cardinal in his rookie 1903 season. The Cards then traded him away. Brown went on to greatness, anchoring the pitching staff of the great Chicago Cubs of 1906 to 1910.

This was a grand time to be a ballplayer or a fan. Both had choices. Yet it was a devastating time to be an owner of an established club like the Cardinals. They began losing personnel and money. Sid Keener estimated season-to-date attendance figures in the May 9 St. Louis Times:

- Cardinals: 24,200 fans in 11 games

- Browns: 37,800 fans in 12 games

- Terriers: 55,900 fans in 16 games

(inc. about 20,000 on opening day)

Keener noted that, if anything, he was erring on the high side. With the big salaries and low gate receipts, he concluded, “There’s a crash coming surely.”

Steal players, the Feds [the new league] did. The war hit home when two of the Cards’ starting outfielders, “Rebel” Oakes and Steve Evans, jumped to the new league for significantly higher salaries than they had before. The Cards’ third starting outfielder, Lee Magee, was tempted by a huge Federal League contract, but stayed put, at least for now. “I’m ready to play my entire career with the Cardinals…I’m a man of my word,” he told the St. Louis Times on March 23. (Magee did jump to the Feds the following year and was later banned from organized baseball for betting against his team and “fixing” games. The man who was once called “the coming Ty Cobb of the National League” never realized that potential.)

MORE LOSING WAYS

The St. Louis Browns had made serious runs at the American League pennant in 1902 and 1908, yet they too had many losing seasons. In the past five years (1909-1913), they had never finished higher than seventh place, averaging 100 losses a year. They had a new manager, the creative and college-bred Branch Rickey. Browns owner Robert Hedges had hired Rickey, the former University of Michigan baseball coach, as a scout and executive. Rickey was to help set up a farm system of minor league teams. When Browns manager George Stovall spat tobacco juice on an umpire during a 1913 dispute, he was relieved of his job, and Rickey took over as manager late that season. When war with the Federal League broke out, plans for the farm system were shelved.

AN INAUSPICIOUS START

The Cardinals had experienced 12 years of futility, posting only one winning season (75-74 in 1911) and finishing an average of more than 40 games out of first place. They had not recovered from the 1902 birth of the AL’s Browns, who had stocked their team by signing almost all of the Cards’ top players in 1901.

The Cards picked up in 1914 where they left off in 1913, losing 12 of their first 19 games. Local papers were full of stories that pitching great Christy Mathewson (Matty) would soon take over as manager of the Cardinals. All Miller Huggins could do was ignore the stories. All he could do was his job.

In early May, Huggins also had to deal with stories of a row with his top pitcher, Slim Sallee. He had won 50 games for the team since 1911. The slender, funloving southpaw, in his seventh year with St. Louis, had an up-and-down relationship with Huggins. In 1913, he won almost 40% of the Cards’ victories (19 of 51). In May 1914, the team gave him a $500 raise to cure his unhappiness.

And then…the Cardinals started winning. Huggins had spoken of “the perfection of teamwork” that he needed on a team with no stars. On May 19, the team reached .500 (15-15). They had a pitching triumvirate that was chalking up wins and turning heads.

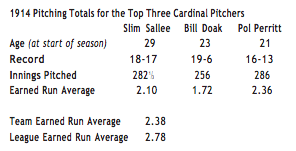

First, there was Slim Sallee. After he hurled a shutout in late June, the Post-Dispatch was moved to write, “To watch Sallee when he’s right and ambitious is to see perfection in pitching.” Then there was young spitballer Bill Doak, who had entered the season with only two career wins. When he beat Grover Alexander and the Phillies on May 16, 1-0, the quiet hurler was quickly gaining recognition. He would complete a spectacular first full season, with a league-leading 1.72 earned run average and two wins over Mathewson. The third member of that rotation was Pol Perritt. Huggins had spent countless hours working with “Polly,” as he called one of his favorites.

The team would hardly miss pitcher Bob Harmon, who had earned 68 victories for the Cardinals from 1909 to 1913. He too went to Pittsburgh in the Konetchy deal. In the short span of one week at the end of June, the Cardinals hurled three shutouts, two by Doak and the 1-0 gem by Sallee over Harmon.

It was his position players whom Huggins had to juggle and where he really had to scramble. All season long, he explored combinations, switched men around, and nurtured talent. Besides the loss of two outfielders to the Feds, shortstop Arnold Hauser was gone, victim of a nervous breakdown. And if Doak and Perritt weren’t household names, what about Miller and Wilson?

“Jack Miller is the most valuable player in the National League today. He isn’t spectacular. But he’s a fighter; he’s hustling every inning of the game…He doesn’t crave the spotlight… just wants to win.” – Sid Keener, St. Louis Times August 1, 1914

The key man on the “no-name” Cardinals was an infielder by the name of John “Dots” Miller. He came to St. Louis in the Konetchy trade with Pittsburgh, where he was the double-play partner of the great Honus Wagner. Miller quickly became the anchor of the Cards’ infield and leader of the team, splitting his time between first base (91 games) and shortstop (60 games).

“Jack is as modest as a schoolgirl,” wrote The Sporting News on August 13, “…without ambition other than to win games.” Miller Huggins recognized Miller’s value when he made Dots the centerpiece of the trade. Three months into the season, on July 18, the Cards skipper pointedly told the St. Louis Times, “I wouldn’t trade Jack Miller for any player in baseball today.” He would hit .290 for St. Louis that year. The only other regulars to hit above .265 were catcher Ivey Wingo, at .300, and outfielder Lee Magee, at .284.

“THE CHIEF” OF TRIPLES

Owen Wilson was another player who came to St. Louis in the big trade. Known as “the Chief,” he helped plug the holes in the outfield. Best known for hitting 36 triples in 1912 (still by far the all-time single-season record), in 1914 he appeared in 154 games, hit 259, and covered a lot of ground in the field. Both Miller and Wilson knew something about winning. They were members of the 1909 World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates.

Manager Huggins had another steady infielder he could count on. The 36-year-old veteran would lead the league in walks for the fourth time and steal 32 bases in 1914. His name? Miller Huggins.

The Cardinals also had two talented young catchers. One was 23-year-old Ivey Wingo, in his third full season with the team. The other was a 20-year-old who led National League backstops in fielding percentage in his first full season, Frank “Pancho” Snyder. Another young National League catcher, Hank Severeid, would soon join the St. Louis Browns. All three would have long careers, and remarkably, each would catch more than 1,200 big-league games (1,233, 1,247, and 1,225 games, respectively; ages at the start of the 1914 season).

In early July, the Cardinals beat the powerful New York Giants three straight times, highlighted by Doak’s win over Matty and a Perritt shutout. The New Yorkers, National League champions the last three years (by an average margin of 10 games), saw their lead over the Chicago Cubs sliced to just 21⁄2 games. The Cardinals were in heady territory, third place, and only four games out.

The Boston Braves were dead last with a 30-41 mark, an improvement over their July 4 record of 2640. A few days later, after they twice beat St. Louis, Braves secretary Herman Nickerson made a puzzling statement to the Post-Dispatch. “We do not consider ourselves extremely out of the pennant hunt,” he said. On July 30, the Cardinals came to Boston. In a thrilling series, the Braves swept St. Louis four straight times, by the scores of 2-1, 2-0, 4-3, and 1-0. Much of the series was played in a steady rain, and the Cardinals lost twice in the ninth inning and once in the 10th. The Braves had moved above .500 (46-45) and were for real. They had gone 20-5 since July 4.

Still the Cardinals persisted. Despite a rash of injuries, they split a four-game set in New York’s Polo Grounds. On August 10, the Giants’ arrogant manager, John McGraw, proclaimed, “I have no doubt but that my club will win the pennant. I never had any particular fear of the Cardinals.”

The next day Bill Doak once again bested Christy Mathewson. The Braves kept winning. Through August 17 won 30 of their last 36 games, and Sid Keener wrote of their manager, “George Stallings is such a phenomenal leader because he gets every ounce of playing ability out of each man.” (St. Louis Times, August 18, 1914.)

Then, while the Giants were losing eight of nine games, St. Louis won seven of eight. When the Giants came to St. Louis on August 24, the Cardinals (as well as the Braves, who were due in St. Louis in a few days) had momentum in a crowded four-team pennant race. The showdown was at hand.

Just a few days earlier, the Federal League’s St. Louis Terriers were in the news with a major change. They had been floundering all year and, with the team mired in seventh place, Phil Ball replaced Mordecai Brown as manager with another legend, Fielder Jones. Jones had been the skipper of the “Hitless Wonders,” the 1906 World Champion Chicago White Sox. Jones had been away from managing for a few years and was lured back by a big challenge and even bigger contract (reported as $30,000 for three years). The Globe-Democrat had written of Brown, “He is too much of a good fellow to be a strict disciplinarian.” Baseball Magazine once described Jones as “cool, calm, calculating, mercilessly sarcastic.” Change indeed.

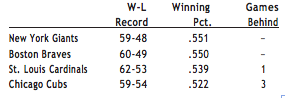

For two days heavy rains postponed the games, and that Cardinal momentum was slowed. New York’s weary pitching staff got some much needed rest. Finally, on August 26, the weather broke, and the Cards and Giants would play a doubleheader. That Wednesday morning, the standings of the top four National League teams looked like this:

United Railways was unprepared for the crowds. Streetcars were filled beyond capacity, and people waited for hours. Some gave up and returned home, while many walked to the ballpark. Two thousand automobiles ringed Robison Field. There had been talk of moving the game to the Browns’ Sportsman’s Park, but Lady Bee quashed that idea: “The bleacher boys have always been our friends, and we cannot go back on ’em now. Robison Field has the largest bleacher capacity of any ball yard in the business.” (The Republic, St. Louis, August 27, 1914.)

St. Louis had not seen a baseball crowd like this since a 1909 Spring Series game (Cards vs. Browns) and an early September 1908 game, when Wild Bill Donovan and the Tigers beat Rube Waddell and the Browns. The Browns had crept to within a half game of the Tigers and first place the day before.

Today Spittin’ Bill Doak took to the mound for the Cardinals, against Rube Marquard, who had 73 wins for the Giants the past three seasons. Miller Huggins led off the game with a walk and scored all the way from second base on a wild pitch. The ball rolled into the overflow crowd standing behind home plate. Under the ground rules for the game, Huggins was able to take the extra base. That run was all the Cards could get and would need, as they held on for the 1-0 victory.

Game two was a showdown between control artist Sallee and the mighty Mathewson. The fans swarmed onto the field during the warm-ups, and Matty had to throw over the children on the diamond. Early in the game, an enormous roar went up when an announcement was made: the Chicago Cubs had just beaten the Boston Braves, also by the score of 1-0.

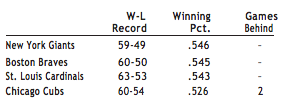

The Cardinals were now in a virtual three-way tie for first place. The standings at that point in time:

What seemed like a dream in pre-season and unthinkable in early May was now a real possibility: a pennant for St. Louis.

The Giants, losers of nine of their last 10 games, were reeling. Their great pitcher Christy Mathewson then responded with one of his greatest games, a two-hit shutout in which he averaged seven pitches per inning. The Giants broke open a tight game with two runs in the eighth and went on to beat St. Louis, 4-0. The Republic gushed the next day, comparing Matty’s performance to “exquisite chiseling or priceless oil on canvass.” Offering a different perspective, the New York Times noted that Giants manager John McGraw “read the riot act to his faltering men” after game one of the doubleheader.

The very next day, August 27, the Cardinals opened a four-game series with the onrushing Braves. The wet weather returned to St. Louis, and the late innings of the first game were played in a downpour. The Cards pulled out a dramatic win in the 10th inning, to pull ahead of the Braves and within one game of the Giants.

On August 29, St. Louis dropped a doubleheader to Boston, 4-0 and 6-4. The Cardinals let the second game slip away, leading 4-2 after seven innings. What hurt almost as much as the loss was that the Braves won that game with three, seldom-used pitchers— Otto Hess, Dick Crutcher, and Paul Strand. Once again the Braves seemed to have the Cards’ number, having now beaten the Cardinals 12 of 18 times.

That was the beginning of seven straight losses for the Cardinals. On Friday, September 4, they were six games out of first place and no longer a factor in the pennant race. The team from Boston, which was becoming known as the Miracle Braves, simply blew past their competition. They won the National League pennant by 10½ games over the stunned New York Giants. St. Louis was just another 2 1⁄2 games back, in third place. The Braves went on to a shocking four-game sweep of the heavily favored Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

There was no pennant in St. Louis in 1914, yet the underdog Cardinals had caught the fancy of the baseball world, rising from their last-place National Legue finish in 1913. Most of all, they had captured the heart of St. Louis, bringing thrills to a city hungry for a winner. Miller Huggins and his team, with a limited budget and no big stars, had led that “perfection of teamwork” to remarkable heights.

STEVE STEINBERG is a baseball historian of the early 20th century. His book Baseball in St. Louis, 1900-1925 was published by Arcadia in summer 2004. He recently completed The Genius of Hug, a revealing book about Hall of Fame Cardinals and Yankees manager Miller Huggins. He lives in Seattle with his wife and three children.