The Vancouver Asashi

This article was written by Tom Hawthorn

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

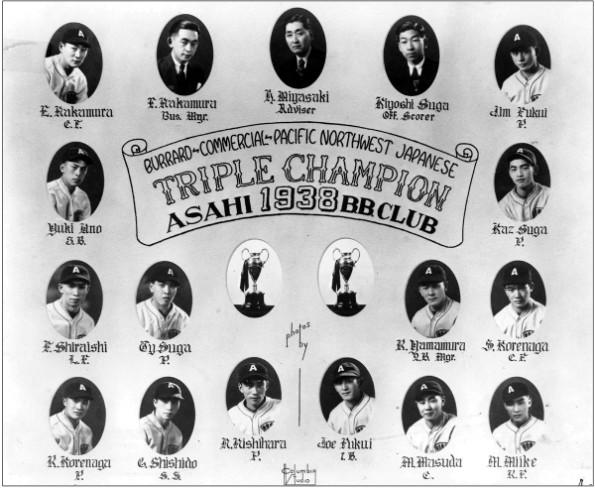

Triple Crown Winners: Champions of three different leagues for 1938. (Nikkei National Museum 2010-30-1-3-15 ab)

A curving pitch appears in slow motion from a hurler not in focus. The voice-over is somber, an older man, remembering. “We were born in Canada,” says Kaye Kaminishi. “We spoke English.” On screen, a batter pushes a bunt toward the first-base line. The image changes. A young man out for a walk is deliberately bumped in the shoulder by a larger man. “On the streets, we weren’t welcome,” Kaminishi says, as the scene returns to the baseball diamond, “but on the field we were the Asahi, Vancouver’s champions.” The video concludes with Kaminishi, a slight, aged man, sitting on a bench wearing the uniform of his Vancouver baseball team, the name spilling in glorious red, Coca-Cola script across the chest, a rising sun on the sleeve.

Kaminishi and his Asahi baseball teammates were among the 22,000 Japanese Canadians interned during the Second World War. The players continued to play baseball in the camps, and brought the game with them as they dispersed across Canada after the war. The release of the Heritage Minute for broadcast in February 20191 cemented the team’s place in Canadian history. The Asahi, whose story was ignored for decades by a disinterested Canadian public, were being celebrated for their achievements as a team of Japanese Canadian players. They were also being acknowledged for having endured the unfairness of discrimination and the cruelty of having been forced into internment.

The team’s story was given further official imprimatur two months later when Canada Post released a commemorative postage stamp celebrating the team. The round stamp featured an image of a baseball with a 1940 team photograph, as well as the team logo, imposed on it. A teenaged Kaminishi appears in the photo. He was born in 1922, and was aged 97 when the stamp was issued.

Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor led to war. Months later, the Canadian government declared that all those of Japanese ancestry, including those born in Canada, must register as enemy aliens. Property was seized, much of it later sold without permission and at a great loss.

When the order came to abandon his home, Ken Kutsukake, the team’s starting catcher in its final year, carefully reduced 31 years of living into a single suitcase. He packed for life in an internment camp: Clothes. Family photos. Baseball shoes. Shin guards. Catcher’s mask. Catcher’s glove. The baseball equipment was a reminder. They could seize his home, deny him a livelihood, compromise his freedom, but no one was ever going to stop him from playing the game he loved.

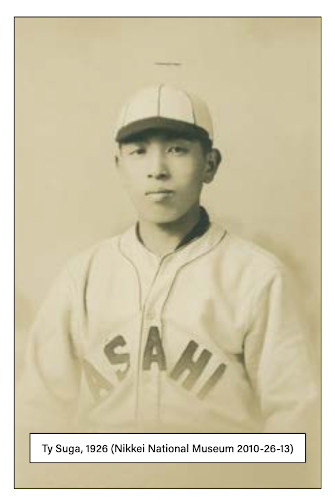

They played baseball in the camps, and eventually held a tournament among teams in British Columbia’s Slocan Valley, with the Lemon Creek All-Stars, featuring several ex-Asahi players and coached by former pitcher Ty Suga, emerging victorious. Kaminishi, who was interned near Lillooet, British Columbia, played on a team of internees who challenged local amateurs. In his one permitted suitcase, he packed his Asahi uniform and pants, as well as his purple Asahi team sweater. Along with Naggie Nishihara’s team jacket, in the possession of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame, these four items are believed to be the only remnants of uniforms left from a team that existed for 27 years.

The aspirations of the Japanese Canadian community in Vancouver were expressed through the play of the Asahi. The team was a symbol of the community’s struggle for equality and respect. Away from the baseball diamond, people of Japanese ancestry, even those born in Canada, were barred from citizenship and the possibility of working as teachers, doctors, lawyers, or accountants. On the baseball diamond, they could compete as equals.

Smaller physically than their opponents, the Asahi adopted a style of play that came to be known as Brain Ball, in which they relied on “small ball” tactics to produce runs – bunting to get on base, judiciously using sacrifice bunting, and basestealing on offense; and superior pitching and fielding on defense. So precise was the work of Asahi batters, it was said they could bunt with a chopstick. In one memorable game in 1927, the Asahi failed to get a hit off a local pitcher named Lefty Delcourt, yet won the game, 3-1, remarkably scoring two runs on a squeeze play without an error when Roy Yamamura sped all the way home from second base.

For residents of Little Tokyo, or Japantown, as the neighborhood surrounding their home diamond at Vancouver’s Powell Street Grounds was known, the Asahi were gods in flannel. “We were the toast of the town,” Kutsukake said in 2003. “To be an Asahi player meant lots to a lot of people.”2

Their style of play and success on the field gained them a following among Caucasian fans as well, though the team heard plenty of racial insults over the seasons. Vancouver’s daily newspapers lazily invoked ugly racial stereotypes and other demeaning descriptions in writing about the players. (A notable exception was the reportage of Clancy Loranger, who started as a sportswriter at the Vancouver News-Herald before moving to the Vancouver Daily Province, where he covered what would be the Asahi’s final game at the end of the 1941 season.) Amateur and semipro baseball in Vancouver was a rough-and-tumble affair in the first half of the twentieth century, and the Asahi took part in their share of dust-ups and brawls, even though they had been instructed to ignore racial slurs, and to not argue with umpires.

The Asahi Baseball Club was formed in 1914, after a visit by a touring Japanese university team fired up local interest in the game. Four years earlier, a Vancouver Nippon Baseball Club had been formed. That team was organized in the wake of a race riot, when residents of Little Tokyo beat back a White mob chanting, “A White Canada!” and “Down with Japs!” The mob torched businesses in nearby Chinatown, and only a desperate defense, including throwing rocks from rooftops, prevented the same destruction happening to their neighborhood.

Asahi, meaning “morning sun,” was a name also used earlier by a local youth group, some of whom came to play for the baseball team. In time the Nippon club collapsed, and the better players were absorbed by the Asahi, which also organized teams for younger players (Athletics, Beavers, Clovers) as a feeder system.

In 1918 the Asahi played against three other teams (Hanburys, Empress Manufacturing Co., and Rose & Howard) stocked with local White athletes in the International League, a grand name for one of several amateur commercial leagues in the city. Over the seasons, the Asahi would move between commercial leagues, and some seasons competed in the City Senior League, the top circuit in the early 1930s when Vancouver lacked a professional team. The Asahi also competed against town teams along the British Columbia coast, and headed south to play other clubs with players of Japanese ancestry along the American coast. In 1921 the Asahi president, Dr. Henry Masataro Nomura, led an Asahi all-star team on a tour of Japan, bolstering the roster with three White players from rival teams.

The Asahi claimed championships in the International League (1919), the Terminal League (1926, 1930, 1932, and 1933), and the Burrard League (1938-40). In 1938 they claimed the Burrard title before sweeping Merritt-Gordon, the Commercial League champion, in three games to claim an interleague city title. That same year they also won the Pacific Northwest title over the Seattle Nippons to claim the coast’s Japanese baseball crown, a title they held for five consecutive seasons before the outbreak of war in Asia.

The Little Tokyo neighborhood included baths, barbers, bakeries, diners, greengrocers, haberdashers, dry-goods stores, ice cream parlors, and silkware merchants catering to a Japanese Canadian clientele without the snubs to be had in the city’s main shopping district a few streets to the west. At the heart of the community was the baseball diamond, which had four rows of wooden bleachers hugging the corner of Dunleavy Avenue and Powell Street. Chicken wire protected spectators from foul balls. The field itself was merciless, a rock-hard pan pitted with stones.

Midge Ayukawa remembered her father, Kenji Ishii, a carpenter, wandering past the Powell Street Grounds, empty lunchpail in hand, dawdling on his way home for supper, hoping to catch a couple of innings of action. “Life was awful, it was so tough,” she recalled. “But at the baseball game he was no longer a hard-working, harassed father. He was like a little boy. He didn’t have much money. He didn’t drink and he never gambled. Going to see the Asahi was about his only luxury.”3

Fans in the team’s early years cheered on such stars as Tom Matoba and Junji “King of Bunting” Ito, as well as the brothers Yo Horii, Mickey, and Eddie Kitagawa. In the 1920s, manager Harry Miyasaki, the first baseman for the 1919 championship team, built the foundations of the culture for which the team would be remembered. He recruited catcher Reggie Yasui and Roy Yamamura, a wicked fielder and fearless baserunner, from the Yamato team, which was based in the city’s Kitsilano neighborhood. Their contemporary was left-handed pitcher Kenichi Suga, nicknamed Ty after Ty Cobb, the best pitcher in club history. The trio was at the heart of the Asahi dynasty of the 1930s.

The great Yamamura, known as the Dancing Shortstop in his playing days, served as the Asahi manager in what would be the club’s final four seasons. He was a harsh taskmaster. “If you can’t stop by glove,” he instructed infielders, “stop by chest.”4 One of the more interesting characters on the squad was Satoshi “Sally” Nakamura, a second baseman born in Vancouver who preferred comedy and singing to baseball. In 1940 he left for Japan, where he would have a long career as a movie and television actor under the name Tetsu “Teddy” Nakamura, appearing in such postwar B-movies as Oriental Evil, Attack Squadron!, and the monster movie Mothra.

The championship teams of the 1930s relied on the likes of sure-handed left fielder Frank Shiraishi, pitcher Naggie Nishihara, infielder George Shishido, and pitcher-outfielder Kaz Suga, who had the team’s top batting average for the final five seasons, including a Burrard League-leading .490 in 1939.

One of the highlights of the era was a series of exhibition games at Con Jones Park against the touring Tokyo Giants. The Terminal League All-Stars included the Asahi’s Yamamura at short. Although the Asahi picked a few star White players from the commercial leagues to bolster their roster, they still fell 9-2 to 18-year-old right-handed phenom Eiji Sawamura, who struck out 15. The previous year, the kid hurler, while still in high school, struck out Charlie Gehringer, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx in succession during an exhibition game against barnstorming major leaguers in Tokyo. Sawamura was killed during the war when his troopship was sunk by an American submarine.

After games, players and fans retreated to Sumiyoshi, a diner with a long counter at 392 Powell Street, just behind home plate. The café was owned by the family of utility infielder Masao (Ken) Shimada. That property, along with private homes and personal possessions, was seized by authorities after the federal government ordered anyone of Japanese ancestry away from the coast. Families were split up. The internees were assigned to ghost towns in the British Columbia interior, where they were forced to live in unsanitary and primitive shacks. Even after the end of the war, the internees were not allowed to return to the coast. They were encouraged to move to war-torn Japan, a country many had never even visited. The restrictions were not lifted until 1949, four years after the war’s end.

Some former players headed to Eastern Canada to rebuild their lives. They brought with them baseball. Ty Suga’s Montréal Nisei team won the city championship in 1949. His kid brother, Kiyoshi, who had been secretary and official scorer for the Asahi, played catcher. Kaz Suga, another brother, spent two seasons with St. Jean of the independent Quebec Provincial League before helping the St. Jerome Lions win the Laurentide League with timely playoff hitting, despite having missed six weeks of the 1953 season after needing 20 stitches in a knee torn while stealing a base.

Ken Kutsukake played amateur baseball briefly before becoming a manager of teams playing out of Christie Pits in Toronto. In 1956, his Honest Ed’s Nisei team won the city’s senior championship. Ed Mirvish, the team’s delighted sponsor, feted them with a banquet, and presented each player a commemorative wristwatch. In 1979 Yamamura received a plaque and a wristwatch for his service as Mr. Ump in the 24th annual Toronto Star Peewee Baseball Tournament at the Canadian National Exhibition.

Thirty-one years passed from the final game in 1941 before the Asahi diaspora had a chance to reunite. Some 300 former players and fans gathered at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto on October 8, 1972. A first attempt to establish an all-time roster of Asahi players, based on memory and newspaper clips, counted 70 athletes. Most of the documents that would have helped in the task were, of course, lost or destroyed during the war.

An indefatigable campaign by Pat (née Kawajiri) Adachi, who celebrated her 101st birthday in 2021, promoted interest in the forgotten story of the Asahi. In 1992 she self-published a scrapbook about the team’s history, and two years later she appeared at a festival at the old Powell Street Grounds, known today as Oppenheimer Park, with several former players, including Mickey Terakita, Katsukake, and, wearing his old uniform, Kaminishi. The Adachi book became a starting point for anyone seeking to tell the Asahi story. In 2003 Jari Osborne’s National Film Board documentary Sleeping Tigers included archival photographs and interviews with surviving players.

That same year, the Asahi as a team were inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. By that time, only 10 former players were still alive, a roster that shortened with every passing year.

By September 18, 2021, the 80th anniversary of the Asahi’s final game, an 8-5 Burrard League playoff loss against a team sponsored by the Angelus Hotel, only Kaminishi remained. As a voice-over by the author Joy Kagawa states in the Heritage Minute, “The team never played another game.”5

TOM HAWTHORN is a speechwriter for British Columbia Premier John Horgan. Hawthorn’s most recent book is The Year Canadians Lost Their Minds and Found Their Country: The Centennial of 1967 (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2017). He served as archival researcher for the 2003 National Film Board documentary Sleeping Tigers: The Asahi Baseball Story. He is an honorary member of Havana’s Peña Deportivo. Born in Winnipeg, he moved to Montréal as a boy, and used earnings from two paper routes to attend Montréal Expos games at Jarry Park.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted:

Adachi, Pat. Asahi: A Legend in Baseball (Etobicoke, Ontario: Coromex Printing and Publishing, 1992).

Hotchkiss, Ron. Diamond Gods of the Morning Sun: The Vancouver Asahi Baseball Story (Victoria, British Columbia: Friesen Press, 2013).

National Film Board of Canada. Sleeping Tigers: The Asahi Baseball Story. Documentary, 50:00. www.nfb.ca/film/sleeping_tigers_the_asahi_baseball_story/.

Notes

1 Heritage Canada. “Heritage Minutes: Vancouver Asahi.” February 19, 2019. Educational video, 1:01. www.youtube.com/watch?v=wBv-MYAf9P0.

2 Tom Hawthorn, “Sun Rises Again for B.C. Ballplayers,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), June 27, 2003: A1.

3 Tom Hawthorn, “Rising Sun Shone,” Province (Vancouver), October 21, 1994: A59.

4 “Rising Sun Shone.”

5 Heritage Canada.