“There’s No Crying in Baseball”: Balls, Bats, and Women in Baseball Movies

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

In an iconic moment from A League of Their Own (1992), Manager Jimmy Dugan (Tom Hanks) asks Evelyn Gardner (Bitty Schram), “Are you crying? Are you crying? There’s no crying! There’s no crying in baseball!”

Baseball is not just a game for boys.

This was never more apparent than when A League of Their Own came to movie theaters in 1992.

Granted, the primary purpose of A League of Their Own is to entertain audiences and rake in profits for its makers. But in offering a fictionalized history of the first season of the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League, which Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley initiated after scores of major leaguers exchanged their flannels for khakis during World War II, the film casts a welcome spotlight on the AAGPBL’s then-long forgotten participants.

The two primary characters in A League of Their Own may be fictional ballplaying sisters, but they are very real products of their era. Dottie Hinson (Geena Davis) yearns for her husband’s return from the war and has no sense of the importance of the AAGPBL. Conversely, playing in the league allows Kit Keller (Lori Petty) a freedom for which she yearns but otherwise could not enjoy, given her gender and the prevailing culture. The film’s impact is summed up by film critic Roger Ebert, who observed, “Until seeing [it], I had no idea that an organization named the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League ever flourished in this country, even though I was 12 when it closed up shop [in 1954]….[Director Penny] Marshall shows her women characters in a tug-of-war between new images and old values, and so her movie is about transition—about how it felt as a woman suddenly to have new roles and freedom.”1

Almost two decades after its release, A League of Their Own remains memorable as much for rescuing the AAGPBL from oblivion as for its now-iconic line, spoken by Rockford Peaches skipper Jimmy Dugan (Tom Hanks), an alcoholic ex-major leaguer who is an amalgam of Jimmy Foxx and Hack Wilson. After be- rating player Evelyn Gardner (Bitty Schram)—as any manager might—Dugan is aghast when Evelyn begins to cry. “Are you crying?” he asks, rhetorically. And he continues: “Are you crying? Are you crying? There’s no crying! There’s no crying in baseball!”

A League of Their Own is not the only film that spotlights females swinging bats and fielding grounders. But it easily is the best-known. Coming in a close second is the original (and best) version of The Bad News Bears (1976), in which Amanda Whurlitzer (Tatum O’Neal), a 12-year-old with a whale of a pitching arm, rescues an inept Little League nine. While stressing that the purpose of Little League is to have fun, the scenario emphasizes that a girl can play ball as well as a boy. Almost three decades later, a dumbed-down remake was released. Here, a girl who is the Pedro Martinez of Little League uplifts the Bears, but all the adult female characters are Playboy Playmate-like bimbos or caricatures of humorless, type-A personality 21st-century businesswomen. In the 2005 Bad News Bears, there is even product placement for Hooters.

If A League of Their Own shows how women once played pro ball in a league of their own, the point of Blue Skies Again (1983), a little-seen baseball fairy tale, is that a woman just might be able to compete alongside men. The one desire of Paula Fradkin (Robyn Barto), the film’s heroine, is “to play second base for the [major league Denver] Devils.” While by no means a great film, Blue Skies Again insightfully examines the struggles of women who attempt to upend the male establishment. At Paula’s first tryout, a white ballplayer tells a black counterpart, “I can’t see [team owner Sandy] Mendenhall being the one to integrate baseball.” When the black man glares at him, the white man begins to sputter. “You know what I mean…” he says, and “integrate” soon is replaced by a word not found in any dictionary, “interfeminate.”

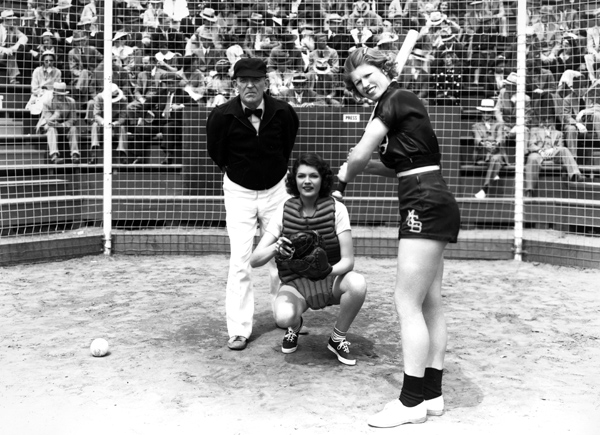

An additional feature spotlighting women ballplayers is Girls Can Play (1937), which despite its proactive title is no ode to sexual equality. It is the tale of an ex-racketeer who organizes a girls’ softball team as a front for selling watered-down liquor. Eventually, he fatally poisons his girlfriend, the team’s catcher, because she “knows too much.” The “girls” of the title are cast primarily for their attractiveness, and are passive sex objects and victims. The film is of note only for the presence of young Rita Hayworth, playing the murder victim, who then was serving an apprenticeship as a Columbia Pictures B-film player.

In Girls Can Play (1937), a young Rita Hayworth serves as catcher for a women’s softball team run by a crook who eventually poisons her with bad liquor.

Various short subjects highlight women baseballers. A typical title is Gracie at the Bat (1937), a comedy whose working title was Slide, Nellie, Slide. “Fireball Gracie,” the featured character, pitches for the Fillies, a girls’ softball team. Gracie has the oddest wind-up, but she literally throws smoke at an opposing batter. Unlike The Mighty Casey, she belts a game-winning homer. But her teammates are a temperamental lot who peruse romance magazines and powder their noses in the dugout.

Similarly, in Fancy Curves (1932), an entry in the “Play Ball with Babe Ruth” series, the Bambino agrees to coach a sorority squad that has challenged a fraternity to a ballgame. “I’ve often wondered why girls haven’t played more baseball,” the Babe observes, adding, “It’s no more difficult than any other sport they take part in.” Nonetheless, his charges are tired stereotypes. After singling, one of the women produces a pocket mirror and powders her face while on first base. The girls inflict damage on the boys only when the Babe dons a wig, swishes up to home plate, and pinch hits a homer. This denouement also is employed in the animated Casey Bats Again (1953), in which a father organizes his daughters into a girls’ team and dresses in drag to enter the game and drive in the winning run.

Some high-profile on-screen baseball aficionados have been women. Easily the most celebrated is Annie Savoy (Susan Sarandon) in Bull Durham (1988), who memorably expresses her belief in the “church of baseball.” But Annie’s idea of baseball worship is not only spiritual. She is highly sexed, and readily sleeps with her ballplayers of choice. An altogether different female fan is Aunt Mary (1979), the fact-based account of a Baltimore spinster and die-hard baseball devotee (Jean Stapleton) who coaches a sandlot ball club. The story of Mary Dobkin shows how the unlikeliest of women can do a “man’s job” and function in her own modest way as an activist. Conversely, Gloria Thorpe (Rae Allen), a nosy female sportswriter, is a villain in Damn Yankees (1958). Gloria is determined to unravel the mystery of Joe Hardy, savior of the Washington Senators, and her snoopiness implies that women have no business in the press box.

Across the decades, bats, balls, and women have mixed in non-baseball films. An instant-classic baseball moniker is found in Whip It (2009), the saga of female roller derby players who are known to their fans by nicknames. The lead character (Ellen Page) chooses one that a baseball-lover will embrace: Babe Ruthless!

Then there is Katie O’Hara (Ginger Rogers), the heroine of Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942), an American who finds herself in Paris just before France falls to the Nazis. Upon being asked where she was born, Katie proudly replies, “Parkside Avenue, Brooklyn.”

“Near Ebbets Field?” is the response.

“Foul balls used to light in my backyard,” Katie quips, before sighing, “Dem lovely bums.”

In Woman of the Year (1942), all it takes is an afternoon at Yankee Stadium to transform highfaluting, baseball-ignorant political columnist Tess Harding (Katharine Hepburn) into an ardent rooter.

Marjorie Winfield (Doris Day) wants to play with the boys — for a while, at least — in the 1951 film On Moonlight Bay.

One of the most fascinating portrayals of a distinctly pre-feminist woman ballplayer is found in On Moonlight Bay (1951). Doris Day plays Marjorie Winfield, a tomboy jock. In a game in which her teammates and opponents are boys, she promptly bashes a triple. Then she steals home. But Marjorie’s athleticism is treated as a passing phase of her young life. One look at the handsome boy-next-door (Gordon MacRae) and Marjorie readily exchanges her mud-stained flannels for a frilly dress. Her mother shows her how to enhance her bosom, telling her, “Sometimes nature needs a little help.” As their first date concludes, the lad calls her “the most beautiful and the most feminine girl I’ve ever met.” As they kiss goodnight, Marjorie’s white-gloved left hand pushes aside forever the cap and ball that are resting on the table beside her.

Thankfully, not all pre-feminist women were so easily swayed away from sports. Leave it to Lucy—as in pre-I Love Lucy Lucille Ball—to play a 1940s woman who oozes spunk and swings a mean bat. In The Dark Corner (1946), Lucy is Kathleen Stewart, the newly-hired secretary of a troubled private detective (Mark Stevens). One evening, the pair visits a penny arcade. After swatting at pitches in a batting cage, Kathleen explains her prowess by noting, “My father was a major league umpire.” When her boss makes a pass at her, she quips, “I haven’t worked for you very long, Mr. Galt, but I know when you’re pitching a curve at me—and I always carry a catcher’s mitt.” He defends himself by noting, “No offense. A guy’s gotta try to score, doesn’t he?” She responds, “Not in my league.”

In Hollywood movies across the decades, baseball often has symbolized wholesome, mom’s-apple-pie Americana. This representation radiates from Cass Timberlane (1947), based on a Sinclair Lewis novel, which charts the evolving relationship between the title character, a widowed, middle-aged, small-town Minnesota judge (Spencer Tracy) and Virginia Marshland (Lana Turner), a much younger woman from the proverbial other side of the tracks. Clearly, the judge is respectable. But how do we know that the same can be said for Virginia? Because, early on, we see her immersed in a spirited softball game.

Despite the prevailing post-World War II culture, in which men were expected to rule the family and women to embrace femininity while staying home and baking cookies, an enlightened male still could be supportive of a female athlete. Virginia and Cass eventually marry. As Cass nervously awaits the birth of their child, he and a nurse peer through a hospital window at eight newborns. “You need one more for a baseball team,” Cass declares. “Ah, save that spot in the outfield for young Timberlane, will ya!”

The nurse poses a question: “Supposing the baby’s a little girl?”

“Oh, that’s so much the better,” Cass responds.

“Mrs. Timberlane’s a very fine ballplayer herself.”

ROB EDELMAN is the author of “Great Baseball Films” and “Baseball on the Web”. His film/television-related books include “Meet the Mertzes”, a double-biography of “I Love Lucy’s” Vivian Vance and fabled baseball fan William Frawley, and “Matthau: A Life” — both co-authored with his wife, Audrey Kupferberg. He is a film commentator on WAMC (Northeast) Public Radio and a contributing editor of “Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide”. His byline has appeared in “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game”, “Baseball and American Culture: Across the Diamond”, “Total Baseball”, “The Total Baseball Catalog”, “Baseball in the Classroom: Teaching America’s National Pastime”, and “The Political Companion to American Film”. He authored an essay on early baseball films for the DVD “Reel Baseball: Baseball Films from the Silent Era, 1899-1926”, and has been a juror at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s annual film festival. He is a lecturer at the University at Albany, where he teaches courses in film history.

Sources

- Edelman, Rob. “Baseball at the Movies.” culturefront, vol. 8, no 3 & 4 (Fall, 1999): 49–52.

- ———. “Baseball’s Cinematic Presence Mirrors America’s National Spirit.” Memories & Dreams, vol. 25, no. 2 (Spring, 2003): 5–8.

- Wood, Stephen C. and J. David Pincus. Reel Baseball. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland & Company, 2002.

Photo credits

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY.

Notes

1 Roger Ebert. “A League of Their Own.” Chicago Sun-Times, July 1, 1992.