Tip O’Neill: A Season Of Firsts

This article was written by Dennis Thiessen

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

Tip O’Neill was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1994. The opening sentence in the Hall’s online tribute reads: “James Edward ‘Tip’ O’Neill was a sensational hitter who slugged his way to the top of the American baseball ranks during the 1880s.”1 O’Neill was the most valuable batsman on the St. Louis Browns,2 champions of the American Association for four years in a row (1885-1888) and world champions in 1885 and 1886.3

Tip O’Neill was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1994. The opening sentence in the Hall’s online tribute reads: “James Edward ‘Tip’ O’Neill was a sensational hitter who slugged his way to the top of the American baseball ranks during the 1880s.”1 O’Neill was the most valuable batsman on the St. Louis Browns,2 champions of the American Association for four years in a row (1885-1888) and world champions in 1885 and 1886.3

During the 1886 world championship, O’Neill was the leading batsman in the six-game series, hitting .400, with four extra-base hits (two home runs and two triples). O’Neill was at his best when he batted for average and power, a combination that was on full display in his record-breaking season of 1887.

Baseball historian David Nemec describes O’Neill’s extraordinary batting achievements of 1887 as “perhaps the most dominant offensive season in history,”4 a dominance that, in an earlier book, he defines in terms of leading in the most batting categories.5 In this season of soaring achievements, O’Neill enthralled fans throughout the American Association with his multihit games, numerous hitting streaks, timely extra-base hits, and run-producing prowess.6 In this season of firsts, O’Neill not only ranked first in most batting categories but also did so with marks that set major-league records.

The following three sections illustrate some of O’Neill’s record-breaking performances in batting for average, batting for power, and batting for both average and power.

BATTING FOR AVERAGE

Tip O’Neill is best known for his batting championship in 1887, a season in which he hit .492. This percentage was the highest single-season batting average ever achieved in the American Association since its inaugural season in 1882, and better than any National League average since its inception in 1876. In subsequent years O’Neill’s .492 mark appeared in most record books as the highest average in two lists, among those batters who were the single-season league leaders in batting average, and among those who hit .400 or higher.7 From 1969 onward, however, most sources cite O’Neill’s 1887 average as .435, which relegates his average to second-best on the all-time list of single-season batting champions, behind Hugh Duffy’s 1894 record of .440.8

Between 1888 and 1968, record-keepers were uncertain about how best to treat the controversial change made in one of the scoring rules for the 1887 season: a batter was assigned a hit and a time at bat for a base on balls.9 Most record books added a note indicating that O’Neill’s batting average occurred in a season in which bases on balls counted as hits. Others were more critical of O’Neill’s record, and sought to discredit the season and any other record made in 1887.10 Those who chose to honor the scoring rules of the day (traditionalists), albeit qualified with an asterisk, stood in tension with those who wanted to ensure that, to the greatest extent possible, the calculation of batting records in every season is based on the same scoring rules (revisionists). This debate came to a head in the late 1960s.

Two initiatives resulted in the revision of O’Neill’s average and the loss of his standing as the batsman with the all-time single-season record for the highest batting average. In 1968 the Special Baseball Records Committee developed a code of rules governing record-keeping procedures, one of which stated that “bases on balls shall always be treated as neither a time at bat nor a hit for a batter.”11 Coinciding with this decision, Information Concepts Incorporated (ICI) completed the most thorough study ever conducted into the batting statistics of nineteenth-century players.12 Following the decision of the Special Baseball Records Committee, ICI did not count walks as hits or times at bat. Accordingly, ICI recalculated O’Neill’s average to .43513 and in 1969 this revised average was reported in the “Big Mac.”14

In 2001 O’Neill’s average was part of another revision, this time based on the resuscitation of the walk-as-a-hit rule. Jerome Holtzman, Major League Baseball’s official historian, turned back the clock with his declaration: “If a walk was a hit in 1887 it should stand as a hit forevermore.”15 Based on the statistics on hits, bases on balls, and times at bat determined by ICI in the late 1960s, O’Neill’s average was adjusted to .485,16 returning him to the top of the list with the best all-time single-season batting average. However, despite Holtzman’s ruling, most record books and online databases, with the exception of Total Baseball,17 continued to report batting records based on the normalized code introduced by the Special Baseball Records Committee, which for the 1887 season meant a walk would not be counted as a hit or a time at bat. Consequently, O’Neill’s batting average continued to be listed in most sources as .435.

Mindful of this traditionalist-revisionist debate about O’Neill’s changing 1887 batting average, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, displays a poster entitled, “Highest Batting Average in a Season Since 1876.” It features a photo of Hugh Duffy and his .440 average in bold print. In the bottom half of the poster, there is an 18-line statement that suggests how O’Neill can also be considered for the highest single-season batting average:

For record books that regard the National League’s first year (1876) as the start of major league play, Boston’s Hugh Duffy is generally cited for holding the mark for highest single-season batting average: .440 in 1894. But another player from baseball’s early days has a legitimate claim to the title. In 1887, baseball implemented two rules which lasted just one season: a walk counted as both a base hit and at bat (today it counts for neither), and a strikeout occurred after four [italics in original], not three, strikes. At season’s end, more than a dozen players posted batting averages above .400, with Tip O’Neill leading the way with a .485 mark. While one cannot retroactively “correct” for the advantage batters gained for the extra strike, most modern-day statisticians have accounted for the unusual walk rule. In so doing, O’Neill’s mark has been retroactively dropped to .435.18

In sum, on at least two occasions, O’Neill’s officially declared batting average was the all-time single-season record in the major leagues: in 1887 when Wheeler Wyckoff, the secretary and president of the American Association, confirmed that O’Neill was the batting champion of the Association with an average of .492, and again in 2001, when Jerome Holtzman endorsed his recalculated average of .485, adding in parentheses, “still the record.”19 In those sources that list the progression of records over the years, O’Neill’s revisionist average of .435 appears as the single-season record in the major leagues between 1887 and 1893, with Duffy’s .440 average as the record from 1894 onward.20

The following two sections describe some of O’Neill’s power records and average-plus-power records, marks that are not explicitly entangled in this traditionalist-revisionist debate.

BATTING FOR POWER

O’Neill was a line-drive hitter who most times made solid contact, driving the ball with considerable force to all fields. Although he was taller and heavier than many of the major-league players in the 1880s,21 Tip used a wagon-tongue bat that was smaller than those preferred by most other batsmen.22 O’Neill seemed to appreciate the importance of bat speed, something he could more effectively control and quickly generate with a smaller bat. As the season unfolded, O’Neill was variously applauded for his power with such appellations as the “champion slugger”23 or “the hardest hitter in the profession.”24

In 1887 O’Neill led the American Association with 52 doubles, 19 triples, and 14 home runs. His total of 85 extra-base hits established a new single-season Association record for long hits,25 which became the new major-league record as well. Hugh Duffy tied O’Neill, getting 85 long hits in 1894. In 1920 Babe Ruth’s 99 long hits eclipsed their record. Nonetheless, O’Neill is the only player in major-league history ever to lead the league in a single season in all three extra-base-hit categories.

Across the season, two out of every five hits by O’Neill were doubles, triples, or home runs. Occasionally, he delighted fans with power surges, periods when he drove out long hits game after game with even greater frequency than usual. Such was the case between August 24 and September 5 when he set a record of 12 consecutive games with one or more extra-base hits. During this streak, O’Neill hit .596. Of his 34 hits, 21 were long hits: 14 doubles, 5 triples, and 2 home runs.26 O’Neill scored or batted in 53 of the 135 runs scored by the Browns, who won 11 of the 12 games played during his extra-base-hit surge.

In 1927 Paul Waner broke O’Neill’s mark when he recorded one or more extra-base hits in 14 consecutive games. Chipper Jones tied Waner’s 14-game long-hit streak in 2006. Tip O’Neill and Rogers Hornsby (1928) are tied for the second-longest streak of extra-base hits.27

In 1888, W.S. Kimball & Co’s cigarettes released the series “Champions of Games and Sports.” The series featured four baseball players: catcher, pitcher, batter, and fielder. O’Neill was included in the collection to represent the “Champion Base Ball Batter.” (Author’s collection)

BATTING FOR BOTH AVERAGE AND POWER

The 12-game long-hit streak also illustrates O’Neill’s capacity to bat for average and for power, a talent he demonstrated with comparable impact at other points in the season. For example, during a stretch of seven games as part of the Browns’ early-season 15-game winning streak, O’Neill hit .727, with 14 of 24 hits going for extra bases: seven doubles, three triples, and four home runs. In this historic week, he also hit for the cycle twice, in a six-hit outburst in a game against Cleveland on April 30 and in a five-hit performance in a game against Louisville five games later.28

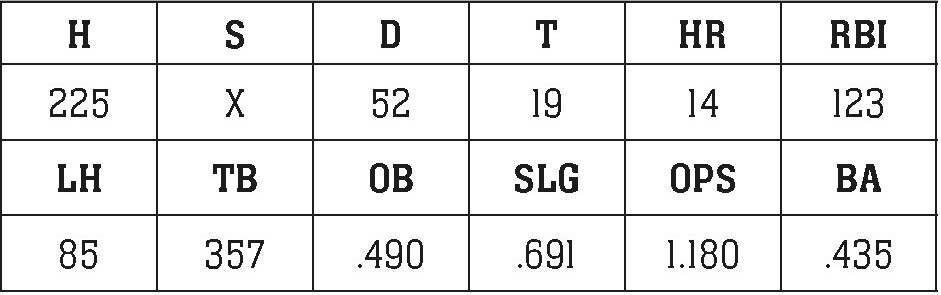

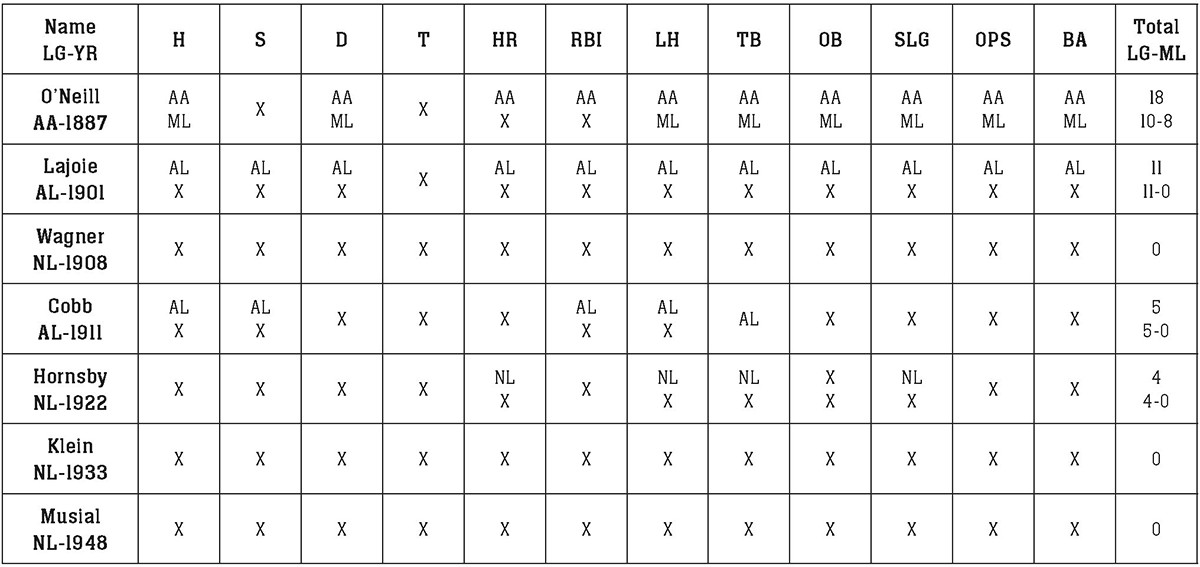

In a season-long milestone of batting for average and for power, O’Neill won the Triple Crown. To win this honor, Tip led the American Association in hitting safely (Batting Average), in driving the ball for distance (Home Runs), and in producing runs (Runs Batted In).29 In addition to the three batting categories that constitute the Triple Crown, O’Neill headed the AA list in eight other categories, extending his dominance to 11 of the following 12 batting categories:30

H-Hits; S-Singles; D-Doubles; T-Triples; HR-Home Runs; RBI-Runs Batted In; LH-Long Hits; TB-Total Bases; OB-On-Base Percentage; SLG-Slugging Percentage; OPS-On-Base plus Slugging Percentage; BA-Batting Average; X-indicates that O’Neill did not lead the AA in singles

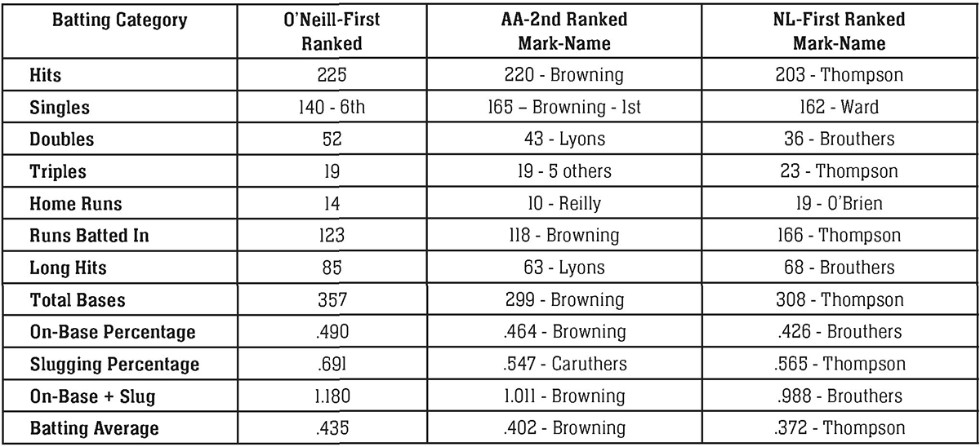

Though O’Neill faced pitchers under the same conditions and rules as all other major-league batsmen, he fared much better than his peers on almost every measure.31 Of the 11 batting categories in which he led, O’Neill broke the American Association record in 10 categories (all except triples). Nine of these stand as single-season records in the 10-year history of the Association.32 Eight of O’Neill’s 10 AA records both exceeded previous NL marks33 and endured as major-league records for the era (1876-1892).34

With most records in the major leagues, “records are made to be broken,” the old adage goes. Seven of the single-season major-league records O’Neill established in 1887 were broken in the next era (1893—1900) and one in 1920.35 However, a more recent adage, namely, some “records will never be broken,”36 also applies. O’Neill is the only batsman who, in a single season, not only led in the most batting categories but also set the most records in these categories.

In the 1876-1892 era, three other batsmen37 had a season of firsts similar to that of O’Neill: in 1876, Ross Barnes led in 10 categories, in the NL only (all except Home Runs, Runs Batted In);38 in 1883, Dan Brouthers was first ranked in nine categories (all except Singles, Doubles, Home Runs) in both the NL and the major leagues; and in 1884, Fred Dunlap finished at the top of eight categories (all except Singles, Doubles, Triples, Runs Batted In) in the Union Association, seven of which were also first-ranked in the major leagues.39

In this era, O’Neill has the all-time single-season league record for leading in 11 batting categories while Brouthers holds the all-time single-season record for leading in nine batting categories in the major leagues. In the number of league-plus-major-league rankings, O’Neill’s 19 firsts (11 in the AA plus 8 in the major leagues) edges Brouthers’ 18 firsts (nine in the NL plus nine in the major leagues) in the total number of batting categories in which they respectively led.

On the number of records established in the 12 categories, O’Neill broke a total of 18 records, 10 in the AA (all except Singles, Triples) and eight in the major leagues (all except Singles, Triples, Home Runs, Runs Batted In), a sum that was well ahead of those achieved by Barnes, Dunlap, and Brouthers. Both Barnes and Dunlap were in the inaugural seasons of the NL and UA respectively, and thus, in the categories in which they led (10 for Barnes, 8 for Dunlap), they established the first league records. Dunlap also set four records in the major leagues for a total of 12 records in both the UA and major leagues. Brouthers set eight new marks in the same four categories in both the NL and in the major leagues.40

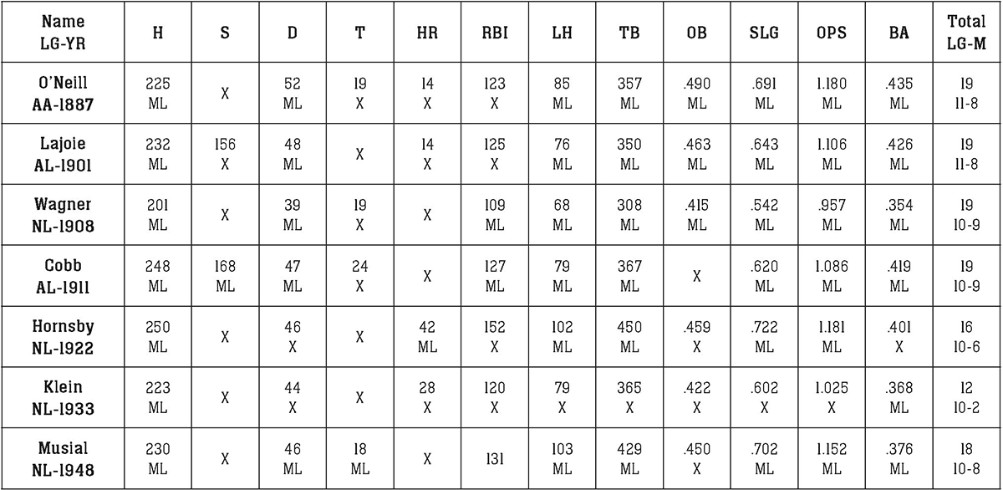

Tables 1 and 2 compare O’Neill’s rankings and records to six batsmen41 who, in subsequent eras (1893-2020), were single-season leaders in 10 or more categories.42 Table 1 reveals that in 1901 Nap Lajoie tied O’Neill’s record of leading the league in 11 batting categories. The last column also shows that Lajoie in 1901, Honus Wagner in 1908, and Ty Cobb in 1911 tied O’Neill’s record of leading in the combined total of 19 batting categories.

As noted above, and also reflected in the final column of Table 2, O’Neill set single-season records in 18 of the 19 batting categories in which he led, 10 in the AA and eight in the major leagues. Nap Lajoie was in the initial season of the American League and, therefore, his leading marks became the first AL records in these 11 batting categories; none were major-league records. The only other batsmen to set records in the 10 batting categories in which they led were Cobb, with five records in the American League in 1911, and Rogers Hornsby, with four records in the National League in 1922.

In this group of champion batsmen, O’Neill is the only one whose marks established both league and major-league records. In short, when it comes to breaking records, O’Neill is ahead of these elite hitters by a significant margin, both in the number of single-season records he broke in the major leagues, and in the total number of records he established in both the AA and the major leagues.

TABLE 1: 1893-2020 SINGLE-SEASON LEADERS IN 10 OR MORE BATTING CATEGORIES

(Click image to enlarge)

TIP O’NEILL: RECORD-BREAKING BATSMAN

In this remarkable season at the plate, O’Neill had numerous record-breaking performances, which, along with his various extraordinary feats, defined the tapestry of his batting supremacy in 1887. Whether one accepts the .492 batting average officially recognized in 1887, his revised and widely acknowledged average of .435 in 1969, or his recalculated but largely ignored average of .485 in 2001, O’Neill either held the record for the highest single-season batting average for six years at .435 (since 1894, he is second on the all-time list) or still holds the all-time single-season record at .485 or .492. Most of his other records are not in dispute. For example, O’Neill’s record for consecutive games with one or more long hits lasted 40 years. He is still the only player ever to lead in doubles, triples, and home runs in a single season. Though not records as such, O’Neill’s two cycles in a span of five games and his Triple Crown are both relatively uncommon and noteworthy feats.

As to the extent to which O’Neill had the “most dominant offensive season in history,” to reiterate Nemec’s claim, O’Neill compares favorably to the premier batsmen in both his era and in subsequent eras in the number of batting categories in which he led in the same season. O’Neill set the all-time single-season record for both his league and the major leagues, leading in 11 of 12 batting categories. Nap Lajoie tied his mark in 1901.

What sets O’Neill apart from Hall of Famer Dan Brouthers,43 Ross Barnes, and Fred Dunlap, his three closest competitors in the 18761892 era, and from the six Hall of Famers44 in the eras after 1892 listed in Tables 1 and 2, is the aggregate number of single-season batting records O’Neill established in both the AA and the major leagues. O’Neill’s total of 18 records (10 in the AA plus eight in the major leagues) is unmatched by these batsmen. O’Neill was “first ever” in that he broke the existing records in all but one of the batting categories in which he was first ranked. In record-breaking feats, O’Neill is first among a small but distinguished group of batsmen, each of whom also had his own “season of firsts.”

TABLE 2: 1893-2020 SINGLE-SEASON RECORDS IN BATTING CATEGORIES

(Click image to enlarge)

AA-American Association; AL-American League; NL-National League; LG-League; ML-major leagues.

NOTE: A single “X” in a cell indicates that the batsman did not lead (Table 1) or set a record (Table 2) in both the league and the major leagues. An “X” placed below a leading number or percentage (Table 1) or below a league abbreviation (Table 2) indicates that the batsman did not lead in the category (Table 1) or set a record (Table 2) in the major leagues. “ML” in a cell and placed below either a leading number or percentage (Table 1) or below a league abbreviation (Table 2) indicates that the batsman led in the category (Table 1) or set a record in the category (Table 2) in the major leagues.

In honor of O’Neill’s incredible 1887 season and outstanding career, the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum created the James “Tip” O’Neill Award, which since 1984 is “presented annually to the Canadian player judged to have excelled in individual achievement and team contribution while adhering to baseball ideals.”45 The award is a fitting legacy for Tip O’Neill, the record-breaking batsman, whose standard of excellence and fair play on and off the field provides an exemplar for the many outstanding Canadian players who followed in his footsteps.

DENNIS THIESSEN is a retired professor of education at the University of Toronto. He is the author of Tip O’Neill and the St. Louis Browns of 1887, published by McFarland in 2019. A SABR member since 2012, Thiessen has presented papers on the St. Louis Browns, record-keeping, and Sunday baseball at the Frederick Ivor-Campbell Nineteenth Century Base Ball Conference, and papers on Tip O’Neill, the Woodstock Wonder, and Tip O’Neill, Champion Batsman of 1887, at the Canadian Baseball History Conference.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on research conducted for the author’s book on Tip O’Neill, Tip O’Neill and the St. Louis Browns of 1887 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2019). The title of this article is an adaptation of the title of Chapter 16, in the book.

Notes

1 Tip O’Neill is one of seven major-league players inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame. He is the first of two position players to receive this honor. Larry Walker, the second position player, was inducted in 2007. The other five major-league inductees are pitchers: Phil Marchildon (1976), Fergie Jenkins (1987), Ron Taylor (1993), John Hiller (1999), and Claude Raymond (2005). See “Honoured Members.” Accessed on April 1, 2021 at https://sportshall.ca/hall-of-famers. Tip O’Neill was also one of three baseball players inducted into the first class of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983. The other two players were Phil Marchildon and George Selkirk. See “Inductees.” Accessed April 1, 2021 at http://baseballhalloffame.ca/museum/awards.

2O’Neill’s major-league career spanned 10 years, seven with the St. Louis Browns (1884-1889, 1891), and one year each with the New York Gothams, NL (1883), the Chicago Pirates, Players’ League (1890), and the Cincinnati Reds, NL(1892).

3St. Louis tied the Chicago White Stockings (NL) for the world championship in 1885, each winning three games with one game ending in a draw. The Browns beat the same Chicago team in 1886, winning four games and losing two for the outright world championship.

4David Nemec, ed., “O’Neill, James Edward ‘Tip,’” in Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900. Volume 1. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 589.

5Nemec also described O’Neill as the “runaway leader in just about every batting department.” David Nemec, in The Beer and Whisky League: The Illustrated History of the American Association – Baseball’s Renegade Major League (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons, 2004), 128.

6In 1887 O’Neill played 124 games, missing 12 games due to injuries. He had 69 games with two or more hits, 34 games with three or more hits, 14 games with four or more hits, and four games with five or more hits. He had a 25-game hitting streak and a 22-game hitting streak (7 games at the end of the 1887 season and 15 games at the start of the 1888 season). He is one of only two players to get a hit in nine consecutive times at bat, twice in the same season. Of his 225 hits, 85 (or 38 percent) went for extra bases. In run production, O’Neill scored or drove in 60 runs that tied or put the Browns ahead, and 19 that proved to be the winning runs. O’Neill scored 167 runs, a major-league single-season record at the time; it currently ranks fourth all-time, tied with Lou Gehrig. For a more detailed account of O’Neill’s batting accomplishments in 1887, see “Appendix B: Tip O’Neill – Single-Season Batting Records and Feats in 1887,” in Thiessen, Tip O’Neill and the St. Louis Browns of 1887, 183-188.

7Sporting Life’s Official Baseball Guide 1891 (Philadelphia: Sporting Life, 1891) and Hy Turkin and S.C. Thompson, The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball, Jubilee Edition (New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1951), 240, 532, 542, 552.

8“Leaders: Single-Season Leaders & Records for Batting Averages.” Accessed on April 11, 2021, from https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/bat-ting_avg_season.shtml.

9There was also controversy over a second rule change which required four strikes for a strikeout. The four-strike rule and the base-on-balls-as-a-hit rule were discontinued after one season.

10 Two of the publications that both denigrated the 1887 season for the two rule changes and challenged the credibility of O’Neill’s record were: John Ward, “1887, the Black Sheep of Baseball Records,” Baseball Magazine 15, 2, 1915: 67-74, and F.C. Lane, “One Batting Championship That Never Was Deserved,” Baseball Magazine, 30, 6, 1923: 547-48, 575.

11The Baseball Encyclopedia: The Complete and Official Record of Major League Baseball (Toronto: The Macmillan Company, 1969), 2328.

12 Baseball’s records prior to 1920 were inconsistent, incomplete, or, in some cases, unavailable, often lost or destroyed as the American Association and other leagues folded. Information Concepts Incorporated (ICI) set out “to build a databank of major league baseball’s existing statistics.” The Baseball Encyclopedia: The Complete and Official Record of Major League Baseball, 5.

13 ICI reported the following batting statistics for O’Neill in 1887: At-Bats – 517; Runs – 167; Hits – 225; Doubles – 52; Triples – 19; Home Runs – 14; Bases on Balls – 50; Stolen Bases – 30; Batting Average – .435; Slugging Percentage -. 691 in The Baseball Encyclopedia: The Complete and Official Record of Major League Baseball, 1310. The ICI statistics are available through the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. “American Association, I.C.I. Statistics, 1887: Batting and Fielding Record, O’Neill” (Cooperstown, New York: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Microfilmed, 2002).

14 “Big Mac” became the nickname of the following 2,348-page encyclopedia The Baseball Encyclopedia: The Complete and Official Record of Major League Baseball. For an account of ICI’s research project and the development of The Baseball Encyclopedia, see “Big Mac,” in Alan Schwartz, The Numbers Game: Baseball’s Lifelong Fascination with Statistics (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2004), 92-109.

15 Jerome Holtzman, “An Important Change to the Official Record of Major League Baseball.” Accessed on May 13, 2017, from https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/why-is-the-national-association-not-a-major-league-and-oth-er-issues-7507e1683b66.

16 Based on the statistics generated by ICI, The Baseball Encyclopedia: The Complete and Official Record of Major League Baseball reported that O’Neill had 517 times at bat, 225 hits, and 50 bases on balls. Walks were no longer counted as hits or times at bat. O’Neill’s batting average was revised to .435 (225 hits divided by 517 times at bat). Following Holtzman’s declaration in 2001, O’Neill’s 50 walks were again counted as hits and times at bat and included in the recalculation of his batting average to .485 (225 hits + 50 walks divided by 517 + 50 times at bat).

17In Total Baseball, O’Neill’s .485 batting average appears in the historical profile of “1887,” the “Players Register,” in second place on the “Batting Average” list in “The All-Time Leaders – Single Season” (Levi Meyerle is first with an average of .492 in 1871), and the leader in “Batting Average” in “The Annual Record – 1887 American Association.” John Thorn, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman, Total Baseball: The Ultimate Baseball Encyclopedia, Seventh Edition (Kingston, New York: TOTAL SPORT Media Publishing, 2001), 551-52, 1066, 2065, 2326; and John Thorn, Phil Birnbaum, and Bill Deane, Total Baseball: The Ultimate Baseball Encyclopedia, 8th Edition (Toronto: SPORT CLASSIC Books, 2004), 38, 1512,2438,2459,2485.

18 The author took a photograph of the poster during a visit to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, on July 22, 2011.

19 Jerome Holtzman, “An Important Change to the Official Record of Major League Baseball.”

20 “Leaders: Progressive Leaders & Records for Batting Averages.” Accessed on March 27, 2021, from https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/batting_avg_progress.shtml.

21In 1887, O’Neill was 6-feet-1-inch tall and weighed 187 pounds.

22 O’Neill’s bat probably weighed around 30 ounces, was 30-32 inches long and no more than 2¼ inches in diameter (below 2½ inches, the maximum allowed). A wagon tongue bat was made out of ash from the spokes or tongue of wagon wheels on horse-drawn carriages. See Stuart Miller, Good Wood: The Story of the Baseball Bat (Chicago: ACTA, 2011), 113.

23 “Bunched Hits,” St. Louis Sunday Sayings, May 15, 1887: 8.

24 “Local Hits,” The Sporting News, August 13, 1887: 5.

25 In the 1880s, the expression “long hits” was used to describe extra-base hits (doubles, triples, home runs). “The Long Hitters,” St. Louis Republican, August 12, 1887: 6.

26 In six of the 12 contests, O’Neill slugged more than one long hit. For example, he had three doubles on August 24 and a double and two triples on August 30.

27 Lyle Spatz, ed., The SABR Baseball List and Record Book: Baseball’s Most Fascinating Records and Unusual Statistics (New York: Scribner, 2007), 149.

28 A cycle is a single-game example of hitting for average and power. Four players have hit for the cycle three times: John Reilly (1883-2, 1890), Babe Herman (1931-2, 1933), Bob Meusel (1921, 1922, 1928), and Adrian Beltre (2008, 2012, 2015). In 1887 O’Neill tied Reilly for the most cycles in a career and for the fastest two cycles, both completing the feat in a five-game span. For a further discussion of O’Neill’s cycles, see “Two Cycles” in Thiessen, Tip O’Neill and the St. Louis Browns of 1887, 75-78.

29 O’Neill is one of only 15 players to win the Triple Crown. Paul Hines (1878) and O’Neill (1887) are the only players who achieved this feat in the nineteenth century. For the full list of Triple Crown winners, see https://www.baseball-reference.com/awards/triple_rowns.shtml.

30 In the two tables in this section, I include those batting categories that explicitly and directly represent what happens when a player hits the ball, which, in the scoring rules of 1887, included the following five categories: Hits, Doubles, Triples, Home Runs, and Batting Average. “Scoring,” Reach’s Official American Association Base Ball Guide 1887 (Reprinted St. Louis: Horton, 1989), 164. I added two categories that were frequently reported in newspapers in 1887: Single, the one hit that was not a required statistic in 1887, and Long Hits, which simply required the addition of the total number of doubles, triples, and home runs. The other five categories -Total Bases, Runs Batted In, On-Base Percentage, Slugging Percentage, and On-Base Percentage plus Slugging Percentage – each officially approved at different points in the twentieth century – were nonetheless statistics periodically suggested in newspapers and guides by various baseball commentators in the nineteenth century. The 12 batting categories provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding the many facets of how O’Neill combined hitting for average and for power. For batting rankings in the American Association in 1887 in each of the 12 categories, see “Leaders” (Yearly League column). Accessed April 11, 2021 at https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders.

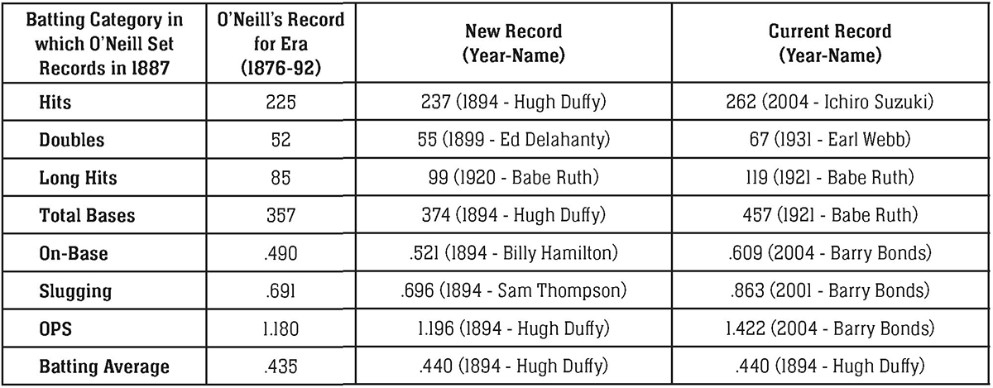

31The following statistics are from the 1887 batting records compiled by Baseball Reference at https://www.baseball-reference.com. The table shows how O’Neill’s first-ranked marks in 11 of the 12 categories (Tip was sixth in Singles) compare to the second-ranked marks in the AA and the first-ranked marks in the NL:

(Click image to enlarge)

32 O’Neill’s all-time single-season records in the AA include the following: Hits, Doubles, Runs Batted In, Long Hits, Total Bases, On-Base Percentage, Slugging Percentage, On-Base plus Slugging Percentage, and Batting Average.

33In 1887 O’Neill broke the major-league records in the following batting categories: Hits, Doubles, Long Hits, Total Bases, On-Base Percentage, Slugging Percentage, On-Base plus Slugging Percentage, and Batting Average. These records are also the all-time single-season records in the major leagues in this era (1876-1892).

34In their introduction to a section on Lifetime and Single-Season Leaders in batting, fielding, and pitching categories, Gary Gillette and Pete Palmer explain the importance of recognizing the leading performances by era: “Some of the lists are divided by time period in order to more clearly highlight the standout performers of each era. Eight significant eras in baseball history have been defined for this purpose – each is distinguished by rule changes, by large changes in the number of leagues or teams, or by other important factors.” “The Glory of Their Times: The Lifetime Leaders,” in Gary Gillette and Pete Palmer, eds., The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (New York: Sterling, 2008), 1756.

35The following table shows O’Neill’s single-season major-league records in his era (1876-1892) for eight batting categories (first two columns) and, in the third column, the new record, when O’Neill’s records were first broken, and by whom. The fourth column lists the current record, when the record was broken, and who holds the record:

(Click image to enlarge)

36 Numerous observers have compiled lists of records that they believe “will stand the test of time.” For one example, see Matthew Cohen, “The Top 25 Sports Records That Will Never Be Broken,” April, 2012. Accessed on April 11, 2021 at https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1151636-the-top-20-sports-records-that-wilI-never-be-broken.

37 Other batsmen in this era (1876-1892) who led in six or more batting categories in one season include: Deacon White (8 – 1877), Paul Hines (6 – 1878), Cap Anson (7 – 1881), Pete Browning (6 – 1885), Sam Thompson (6 – 1887), Jimmy Ryan (6 – 1888), and John Reilly (6 -1888).

38 Barnes is not credited with any firsts in the major leagues because the NL was the only officially recognized major league in 1876.

39 There is no information available on Runs Batted In for UA batsmen.

40 With only one major league in 1876, Barnes is credited with only 10 records in the NL. Dunlap set major-league records in Hits, Total Bases, Slugging Percentage, and On-Base plus Slugging Percentage. Brouthers set both NL and major-league records in Hits, Runs Batted in, Long Hits, and Total Bases.

41In Table 1, this article relies on baseball-reference.com for the batting statistics for O’Neill and the other six batsmen.

42 Two of the batters listed in Tables 1 and 2 also led in 10 batting categories in another season, Ty Cobb in 1917 and Rogers Hornsby in 1921. Those who led their respective leagues in nine categories: Nap Lajoie (1904), Cy Seymour (1905), Ty Cobb (1909), Heinie Zimmerman (1912), Rogers Hornsby (1920), Joe Medwick (1937), Stan Musial (1943, 1946), and Carl Yastrzemski (1967).

43 Dan Brouthers was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945. Ross Barnes and Fred Dunlap are not in the Hall of Fame.

44 The six batsmen highlighted in Tables 1 and 2 were also inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in the following years: Ty Cobb (1936), Honus Wagner (1936), Nap Lajoie (1937), Rogers Hornsby (1942), Stan Musial (1969), and Chuck Klein (1980).

45Since its inception, Larry Walker has won the James “Tip” O’Neill award nine times, three times with the Montréal Expos, five times with the Colorado Rockies, and once while in the minor leagues. Joey Votto has won it seven times, each time with the Cincinnati Reds. Two others have won the award three times: Justin Morneau, twice with the Minnesota Twins and once with the Colorado Rockies, and Jason Bay, twice with the Pittsburgh Pirates and once with the Boston Red Sox. “James ‘Tip’ O’Neill Award,” Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Accessed April 3, 2021 at http://baseballhalloffame.ca/museum/awards.