Trades from Hell: A Tale of Two Cities

This article was written by William Shkurti

This article was published in Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal

The major league baseball clubs of Cleveland and Cincinnati have much in common. They call the same state home. Both have established a proud tradition that dates back to the nineteenth century, and have enjoyed success and endured failure. They are mid-market teams who can afford to compete when managing resources wisely, but can’t afford to buy their way out of their mistakes.

In the 1960s both teams traded away popular home grown slugging outfielders. The Indians traded away Rocky Colavito, and the Reds traded away Frank Robin son. In both cases the fan base reacted negatively. Both players thrived for their new teams while their old teams continued to struggle. And both trades are still ubiquitous today on lists of “worst trades of all time.”

Yet within a short period of time after these two trades were consummated, the fates of these two clubs diverged. The Cincinnati Reds bounced back to enjoy a dominant decade of success as the Big Red Machine. The Cleveland Indians descended into a pattern of futility that lasted 35 years. Veteran Cleveland sports-writer Terry Pluto even wrote a book about it, titled The Curse of Rocky Colavito.1

But the “common wisdom” in baseball isn’t always the whole truth. Using the tools of modern-day saber-metrics, such as Wins Above Replacement, we take a fresh look at the fates of the two ballclubs in the wake of the trades and demonstrate how and why they diverged. We will begin with the Colavito trade, then the second Colavito trade, followed by the Robinson trade. From there we will examine some other management decisions that shaped the outcome in surprising ways. It will reveal new insights about how the business of baseball and the sport of baseball intersect, not only back then, but what it portends for the present day.

COLAVITO I: “THEY WON’T COMPLAIN IF WE WIN”

In 1959 the Cleveland Indians made a surprisingly strong run for the American League pennant. Although the team fell five games short behind the champion Chicago White Sox, they put on a great show that captured the hearts of Cleveland fans. Nearly 1.5 million of them paid their way into Municipal Stadium, reversing a four-year trend of declining attendance and ending speculation about a franchise relocation to Minneapolis.

Credit for the resurgence went to general manager Frank Lane, known as “Frantic Frank” and “Trader Lane” because of his obsession with trading players. In fact, many of the players Lane brought into Cleveland via trades contributed to the team’s 1959 success.2 Rather than rest on his laurels, Lane engaged in an other trading frenzy to improve the club for the 1960 season. Gone were the team’s best all-around player (Minnie Minoso), its winningest pitcher (Cal McLish), and its most promising rookie (Gordy Coleman). But the trade that rocked the fan base most occurred just before opening day when Lane shipped AL 1959 home-run champ Rocky Colavito to Detroit for AL 1959 batting champ Harvey Kuenn.

Rocky Colavito had been a Cleveland Indian since he was signed in 1951. He showed consistent power while working his way through the farm system. He put up good power numbers as a part-time outfielder in 1956 and as a starter in 125 of 153 games in 1957. After manager Joe Gordon installed him as the regular right fielder in 1958, he blossomed. He batted .303 with 41 home runs and 113 RBIs. His On Base Plus Slugging of 1.024 ranked him third in the American League behind only future Hall of Famers Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle.

His popularity among the Tribe faithful grew accordingly. A handsome young man with a modest demeanor, he attracted a loyal following among young people.3 During the 1959 pennant run, he had tied Harmon Killebrew for the league lead in homers with 42 and was one shy of Jackie Jensen for the lead in RBIs with 111. He cemented his hold on Cleveland fans on a muggy June night in Baltimore when he became only the second American League player to hit four home runs in a nine inning game. The other was Lou Gehrig.4

All this made his Topps baseball card the most valuable piece of cardboard in Northeast Ohio in the summer of 1959. But while Colavito’s power numbers stayed strong in 1959, his batting average dropped from .303 to .257. Lane said he wanted the team to be more balanced and less dependent on home runs. He traded Colavito to Detroit for Harvey Kuenn on April 17, 1960. The fans objected. “They won’t holler if we win,” Lane retorted.5

But they didn’t win. Many of the players Lane traded for didn’t produce: young pitchers didn’t come through and the team lacked punch. They finished fourth in 1960 at a disappointing 76-78, 21 games out. Attendance plummeted by more than 500,000.

Then in December of 1960, Lane traded away Harvey Kuenn to the Giants for pitcher Johnny Antonelli and right fielder Willie Kirkland. Kirkland was even more of a home-run-or-nothing player than Colavito. That was too much for Indians ownership and when Lane asked for a contract extension they refused. Lane left Cleveland to work for a kindred spirit, Charlie Fin ley in Kansas City. Meanwhile Colavito thrived in Detroit, while Antonelli and Kirkland flopped in Cleveland. Kirkland was himself traded away for aging outfielder Al Smith in 1963.

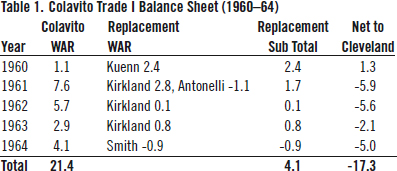

Table 1 documents the ugly outcome of this trade using Wins Above Replacement (WAR) as calculated by Baseball Reference6. It covers the period 1960-64. The results of this trade are unambiguous. Colavito contributed 21 WAR for Detroit and Kansas City over that five-year period.

The players Cleveland received in exchange man aged to contribute a total of only four, thus this trade cost the team a net of 17 wins over five years. And even that number is distorted by Colavito’s off season in 1960, which was probably driven by him pressing too hard after the trade.

As lopsided as this trade looks, it’s important to keep it in context. Between 1960 and 1964 the Cleveland Indians finished with a cumulative record of 392-409, a total of 113 games out of first. So, a switch of 17 games would have been nice, but would not have turned a perpetual also-ran into a contender on its own. But unfortunately for Cleveland fans, this would not be the worst of the fallout from this trade.

COLAVITO II: TRADE FROM HELL ON STEROIDS

Gabe Paul took over the reins as Cleveland’s general manager just before the start of the 1961 season. In ten years as Cincinnati’s GM, he had rebuilt their farm system and gained a reputation as a solid baseball executive. He was credited with building the Reds team that went on to win the National League pennant in 1961. But he would struggle to achieve success with Cleveland.7

Paul decided the team had endured enough turmoil with Lane’s constant shuffling of players, so he decided to stay with the team Lane had put together for the 1961 season They fared no better, finishing fifth, 30 games out. To make matters worse, players Lane had traded away made very visible contributions to their new teams. Rocky Colavito had a near MVP season in Detroit, and former Indians Norm Cash, Don Mossi, Hank Aguirre, and Dick Brown helped the Tigers make a serious run for the pennant.

The only team standing between Detroit and the championship was the New York Yankees. The Bronx Bombers featured former Tribe farmhand Roger Maris, who proceeded to beat Babe Ruth’s single season home run record. Meanwhile, former Tribe prospect Gordy Coleman provided a big bat that helped Gabe Paul’s former team capture the National League flag.

Embittered Indians fans continued to show their disgust. Home attendance dropped by another 225,000 in 1961 to a weak 726,000. While Paul changed managers twice (from Jimmy Dykes to Mel McGaha in 1962 and McGaha to Birdie Tebbetts in 1963) and shuffled players, his team couldn’t break .500. Attendance continued to fade. In 1963 it dropped yet again to a dismal 563,000, second to last in the major leagues, behind only the perennially pathetic Washington Senators.

In 1964 the Indians finished sixth, 20 games out. Attendance ticked up slightly to 653,000, but the team was losing money, and unhappy investors started looking at moving the team to greener pastures like Seattle, Oakland, or Dallas.8 Paul decided the best chance to stabilize the franchise was to bring back Rocky Colavito. Colavito had been traded by Detroit to Kansas City after the 1963 season and had done well there. Kansas City was not interested in trading with Cleveland, but Chicago was. So, Paul engineered a three-way deal where Kansas City shipped Colavito to Cleveland on January 20, 1965, while Cleveland shipped veteran catcher John Romano and two promising but untried rookies—outfielder Tommie Agee and pitcher Tommy John—to Chicago.

At first the trade paid off. In 1965 Colavito batted .287 with 26 home runs and a league-leading 108 RBIs. His presence seemed to energize the hitters around him, many of whom had career years, or near career years. Combined with a corps of young pitchers, the Indians improved to 87-75 (their first winning season since 1959), only 15 games out of first. That brought 935,000 fans back to the ballpark, the best results in five years.

The resurgent Tribe then started off 1966 with a great deal of excitement, but it would not last. Colavito hit 30 home runs, but his batting average dropped 49 points to .231 and he knocked in only 72 runs. The next year after 191 at-bats he was batting only .241 with five home runs and 21 RBIs, and was traded to Chicago on July 29. The Tribe floundered, finished fifth in 1966 and eighth in 1967. Attendance fell again, to 903,00 in 1966 and 663,00 in 1967.

Meanwhile, once again the players Cleveland had traded away blossomed. John Romano had two decent years as a part-time player for Chicago, then was traded to St. Louis where he played very little, then retired. Tommy John would go 14-7 in 1965 on his way to a stellar 26-year career with 288 lifetime wins and 62 WAR. Tommie Agee won the 1966 American League Rookie of the Year with an incredible season where he batted .273, scored 98 runs, hit 22 home runs, knocked in 86 runs, and stole 44 bases. Chicago later traded him to the Mets where he helped the 1969 Miracle Mets get to the World Series and finished sixth in NL MVP voting. Overall, his 12-year career netted 25 WAR.

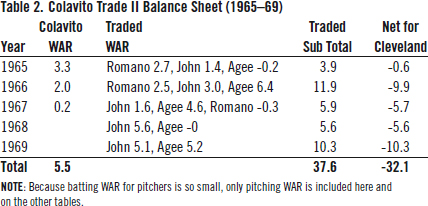

If you add all these up, Cleveland traded away 92 WAR over the next 25 years and received a meager 5.5 in return—certainly a disaster that belongs in the Worst Trades of All Time pantheon. That said, the comparison might be a little unfair. No one could have foreseen Tommy John’s long career and the revolutionary reconstructive ligament surgery that prolonged it. Another way to look at this would be to assess the trade over its first five years to make it com parable to the first Colavito trade as shown in Table 2.

Compared to Colavito I, which cost Cleveland a net of 17 games over five years, Colavito II cost 32. The Frank Robinson trade completed a year later would produce yet another contrast.

ROBINSON: “NOT A YOUNG 30”

Frank Robinson debuted in left field with the Cincinnati Reds in 1956, the same year Colavito arrived in Cleveland. The 20-year-old hit 38 home runs, drove in 83 and batted .290 to capture the National League Rookie of the Year award. His OPS that year trailed only future Hall of Famer Duke Snider among all National League regulars and exceed that of future Hall of Famers Hank Aaron and Willie Mays. He went on to produce Hall of Fame numbers over the next nine years. In 1961 he bashed 37 home runs, drove in 124 and batted .323 while leading the Reds to the National League pennant and capturing the MVP award.

Robinson continued to produce after the 1961 sea son, but the Reds failed to repeat as champs. Owner and general manager Bill DeWitt decided the Reds’ Achilles Heel was poor pitching, so he traded Robin son to Baltimore for pitcher Milt Pappas and two other players after the end of the season on December 9, 1965. The fans were not pleased. DeWitt later described Robinson as “not a young 30,” his age at the time of the trade, a statement he would live to regret.9 Robinson responded, at age 30 in 1966, by winning the American League Triple Crown, the MVP award, and leading the Baltimore Orioles to a World Championship.

That finished Bill DeWitt in Cincinnati (the Reds with Milt Pappas finished seventh, 18 games out in 1966). He sold the team and went on to greener pastures. Ironically, it was DeWitt who as GM of the Detroit Tigers fleeced Frank Lane for Rocky Colavito in exchange for Harvey Kuenn.

Meanwhile Robinson continued to perform at a high level for the Orioles until they traded him in 1971. In 1975 he made history as major league baseball’s first Black manager—with the Cleveland Indians. In 1982 Frank Robinson was elected to the Hall of Fame. All this helped cement this trade as one of the worst trades in history.

William Schneider argues in an article written for the 2020 Baltimore issue of The National Pastime that this trade is not as lopsided as it seems.10 Using WAR similar to the comparison involving Colavito, Table 3 tracks the trade over the six years until Robinson was traded by the Orioles. While Robinson did in fact have a strong six years in Baltimore ( + 32.4 WAR), the players Cincinnati received in exchange accumulated + 24.5 WAR over the same period.

Milt Pappas contributed 5.7 WAR before he was traded by new GM Bob Howsam as part of a multiplayer deal that included reliever Clay Carroll. Carroll contributed 7.7 WAR over the next four years. Howsam also traded outfielder Dick Simpson, who came over in the Pappas deal, for Alex Johnson, who contributed 6.5 WAR before being traded for Jim McGlothlin, who contributed 4.6. and Pedro Borbon, who didn’t contribute much in 1969 or 1970, but would in future years. Over all, the players traded for Robinson contributed only 8.5 WAR less than Robinson over six seasons.

BOTTOM LINE

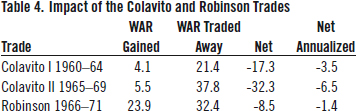

Table 4 displays the WAR of the players the trading team received in exchange for Robinson and Colavito in the first column. The second column shows what Robinson and Colavito produced for their new teams. The third column shows the net over the life of the trade. The final column shows the net on an annualized basis.

This comparison shows the trades hurt both clubs, but the impact of the Colavito trade(s) hurt Cleveland more, particularly the second one. One has to wonder if Cleveland was in fact cursed. When Robinson was traded to Baltimore, he was supposedly an “old” 30. He went on to give Baltimore six great seasons (32 WAR) and then went on to play for five more seasons to age 40 (11 more WAR). Colavito was 31 when he returned to Cleveland. He didn’t smoke, drink, or carouse and never missed significant playing time due to injury or ill health, which should have made him a “young” 31. He only lasted two more years with Cleveland before being washed up at 33.

Still, even this difference is not enough to explain the diverging path of these two clubs. In the first four years after the second Colavito trade (1965-68), the Cleveland club won an average of 82 games a year and drew an average of 840,000 fans. In the four years after the Frank Robinson trade (1966-69), the Cincinnati Reds averaged 84 wins a year and drew an average of 860,00 fans annually. But over the next four-year period, the fortunes of the two clubs diverged. The Indians dropped to 67.5 wins a year between 1969 and 1972 and average ticket sales fell to 640,000 annually. The Reds racked up 94 wins a year from 1970 to 1973 and drew an average of 1,730,000 fans a year. Cincinnati continued to do well the remainder of the decade, while Cleveland stumbled through two more decades of lackluster performance and became the laughingstock of the league. What was going on?

SEEDS OF DESTRUCTION

In the mid-1950s the Cleveland Indians had stood at the summit of the baseball world. Powered by general manager Hank Greenberg’s rich farm system, between 1950 and 1956 they won more games than any other team in either league except for the New York Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers. They drew more fans than any team other than the Yankees. And they made more money than any other team but the Yankees and Dodgers. That made their owners, a consortium of local businesspeople, very happy.11

In 1954 they beat the Yankees to the American League Championship by winning a record 111 games. The upcoming talent in their farm system promised a bright future. But beginning with the 1954 World Series, their fortunes began to slump. They lost four straight to the New York Giants. They missed out on returning to the World Series in 1955 when a late season slump cost them the pennant. In 1956 they finished second again to the Yankees, but this time by nine games. The fans seemed bored with a slow and aging team that was becoming less competitive. Atten dance fell below one million for the first time since the end of World War II.

Since 1949 the team had been owned by a consortium of local businesspeople. At the end of the 1956 season, the club was still profitable and still owned by local investors, but some of the members of the consortium decided to cash out. One of those who decided to stay in was investment banker William Daley, who became the single largest shareholder with 55% of the outstanding stock. Initially Daley and the remaining owners stressed continuity. For example, they kept GM Hank Greenberg in charge and made him a minority partner. But after a disastrous 1957 season where the team fell to sixth place, 21.5 games out, and home attendance dropped for the third year in a row to a miserable 722,000, Daley and the others had a change of heart.12

They forced out Greenberg and turned to Frank Lane, who had just orchestrated a rebound for the St. Louis Cardinals. The Cardinals had finished seventh with a home attendance of 850,000 in 1955, the year Lane took over. Two years later, after a flurry of trades, the Cardinals soared to second and drew 1.2 million fans. But Lane’s relationship with Cardinals president Gussie Busch had deteriorated over Busch’s worries that Lane’s win-now philosophy was trading away too many of the team’s top prospects. That made Lane both eager and available. The Indians’ owners jumped on it, promising him what Gussie Busch wouldn’t, a free hand in player moves.13

As discussed previously, this strategy appeared to work in the short run as attendance rebounded in 1959. But Lane wore out his welcome after trading Colavito and Gabe Paul succeeded him but was unable to show improvement on the field or at the gate. The owners re structured financially in 1962. They sold Paul a 20% ownership share, but that didn’t change anything.

After four years of declining attendance, Daley and the others pressed Paul to cut expenses as a way of protecting their investment.14 Paul did this in a number of ways and a big axe fell on player development. This reached a fever pitch in the 1963 and 1964 seasons. Paul’s trade to bring back Rocky Colavito temporarily reversed the attendance slide, but underlying structural problems remained.

During the 1966 season the Daley consortium decided it was time to sell the team. Cleveland businessman Vern Stouffer, himself a member of the consortium since 1962, stepped up. Stouffer made his money in the food business, including a very popular line of frozen TV dinners.

Stouffer promised to rebuild the team’s decaying farm system and put the franchise back on a winning track. He immediately began to put money back into scouting and player development. To finance his purchase of the team, he sold his food company to Litton Industries, a California conglomerate that made— among other things—the microwave ovens used to heat his TV dinners. Instead of taking the proceeds in cash, Stouffer took it in Litton stock. After all, that stock had increased in value the last 13 years in a row, so he would have the best of both worlds: a baseball team to own and a separate source of growing income.

But three years later, Litton fell on hard times: the stock crashed and took Stouffer’s fortune with it. Stouffer in turn pressed management to cut costs and the farm system took another financial hit. In 1972 Stouffer ended up selling the team to Nick Mileti—also local but also under-financed—and the Indians’ woes continued.15

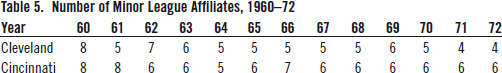

The arc of this sad story is clearly revealed in Table 5. It compares the number of minor league affiliates in this period between the Cleveland Indians and Cincinnati Reds, according to Baseball Reference.

The number of farm clubs is by itself not a perfect measure of a given team’s player development, which also includes scouting, coaching etc., but in the absence of more complete data it should be a pretty good indicator. At the beginning of the sixties both Cleveland and Cincinnati maintained eight teams, which put them in the top third of all 16 major league franchises.

Most major league teams, including Cleveland and Cincinnati, reduced the number of affiliates early in that decade for both financial reasons and in response to expansion from 16 major league teams to 20. But the most significant inflection points come in 1964 and 1971. In 1964 Cleveland winnowed its system down to five teams as a result of pressure from the owners’ consortium to cut costs. Then in 1971 they dropped to four with a second round of cuts in response to an edict from new owner Vernon Stouffer. Indians farm director Hank Peters warned Stouffer that cuts in player development were a form of extended suicide; the results wouldn’t show up immediately, but would with a vengeance in three to five years. In fact the more severe downward spiral in Cleveland’s fortunes began in 1969, five years after the first permanent round of cuts ordered by the Indians’ owners.16

Cincinnati, on the other hand, remained relatively stable at around six affiliates from 1963 on. This was not by accident. Even though the Reds endured some lean years at the gate after the Robinson trade, the ownership maintained a strong player development system. Bill DeWitt kept intact the productive farm system Gabe Paul had developed during his time as owner-general manager 1960-66. When Bob Howsam took over as GM after DeWitt sold the club in 1966, he put even more money into scouting and player development.17

During the time frame 1963-70, the Reds farm system produced the likes of Pete Rose, Tony Perez, Lee May, Gary Nolan, Johnny Bench, Dave Concepcion, and Don Gullett, all of whom became part of the highly successful Big Red Machine of the seventies. That extraordinary collection of talent captured six di vision titles, four National League Championships and two World Series 1970-79.

The Cleveland farm system produced a number of good players in the first half of the sixties, including future All-Stars Sam McDowell, Luis Tiant, Tommy John, Sonny Siebert, Steve Hargan, Tommie Agee, Max Alvis, and Vic Davalillo. Unfortunately for the Indians, once the 1964-65 cost reductions set in, the pipeline started to dry up. The only All-Star caliber players produced by the Cleveland farm system to debut be tween 1967 and 1970 were catcher Ray Fosse and outfielder Richie Scheinblum. Over the next decade, the farm system produced a handful of star players like Chris Chambliss, Buddy Bell, and Dennis Eckersley, but came nowhere close to what was needed.

If you trade for a star player and he produces, that’s still just one player. But if you have a strong farm system, it can produce multiple players. The advantage of a strong stream of rookies is their cumulative effect. For example, the Indians’ home grown All Stars that came up to the majors between 1962 and 1964 added an average of 16 WAR annually between 1964 and 1966—and that’s without Agee and John, who were developed by Cleveland but traded. Running the same calculation for the Cincinnati Reds rookie classes of 1965-68 (Perez, May, Nolan and Bench) shows an average of 18 WAR annually from 1969 to 1971, and that’s without Pete Rose, who came up in 1963. This suggests a strong farm system can produce at least an additional 16-18 WAR annually, much more than any one star.

More than any other factor, the starving of the farm system explains Cleveland’s lean years after the 1960 Rocky Colavito trade. These reductions were justified at the time as necessary because of lack of fan sup port at the box office. It would stay that way until the Jacobs brothers bought the team in 1986 and started rebuilding the player development operation.18

The financial side of major league baseball teams has always been notoriously opaque, because the teams are generally privately owned and free of financial reporting requirements. Yet a significant amount of evidence has emerged since then that raises the question as to whether the cutbacks in the 1960s were really necessary.

A FINANCIAL SHELL GAME

In 1956 the Daley consortium bought the Cleveland Indians for nearly $4.0 million. In 1966 they sold it for $8 million, doubling their money.19 This translates to an annual return of 7.2% when inflation averaged less than two percent annually.20 Quite a good deal if you can get it!

What is missing from this calculation, though, are year-to-year operating results. For example, if the team keeps losing money due to low attendance, investors may have to put in additional cash just to pay the bills. In the example above, if the team lost a million dollars a year for four years, the investment return would be zero, even if the investors could sell the team for four million more than they paid initially. This is what the investors claimed happened to them in the low attendance years like 1963 and 1964 where losses of more than a million dollars a year forced them to cut player development expenses and think about moving the team.21

A baseball team is ultimately a business, not a charity, so it can’t absorb losses indefinitely. But what we do know now is the definition of “losses” is some what elastic and likely exaggerated. In his excellent 1995 study, former sports reporter Jack Torry used publicly available information to put these figures into context. He documented how baseball teams in this era, including the Indians, got IRS approval for a tax writeoff to offset depreciation of their players. Once this is taken into account, the so-called losses are much less.

Using information presented in 1957 and 1958 Congressional hearings on baseball’s antitrust exemption, Torry pointed out that in 1956, instead of the team losing $167,000 as it claimed, the team was able to write off $700,000 in depreciation which meant a $167,000 paper loss was actually a $500,000 profit. Torry also calculated the team’s paper loss of $1.2 million in 1963 was more like $300,000 after tax adjustments.22

A loss is still a loss, but these losses can also be offset in years when the team makes a profit. For ex ample, the team did acknowledge a profit of $609,000 when it drew 935,000 fans in 1965.23 Indians’ management never publicly discussed how much profit they made from the 1959 attendance surge of 1.5 million fans, but it must have been substantial.

We don’t know what the real break-even point was for the Indians ballclub in this period, but we do know that in 1957 the team signed Frank Lane to a contract that guaranteed him a bonus for every fan over 800,000.24 Presumably the Indians’ business savvy owners would not have shared profits with Frank Lane or anyone else if there were not profits. That suggests a break-even point of about 800,000. That number is consistent with the report of a $609,000 profit from an attendance figure of 935,000 described above.

If we examine the home attendance figures for the entire eleven years of the Daley Syndicate’s ownership, it shows some fluctuations, but attendance for those eleven years averages out to 824,000 annually, or just about break-even. The 1956-66 syndicate included some of the wealthiest men in Cleveland with an estimated net worth of over $100 million. And some of them, including Daley, had already pocketed significant profits from their earlier holdings.25 And when Vern Stouffer sold the Indians in 1972, he got back $10 million, two million more than he paid six years earlier.26 This was less than the return the previous investors enjoyed, but still a lot better than return on investment from his Litton stock.

So instead of trying to wring every penny of profit out of a struggling franchise, the Indians owners could have decided to protect the talent pipeline and accept more risk and less profit for themselves, which is what Bill DeWitt and Bob Howsam did in Cincinnati. We don’t know the details about the Reds’ internal finances in this period, but we do know owner/general manager DeWitt bought the team for $4.6 million in 1962 and sold it to a local consortium for $7.0 million in December 1966.27 By comparison the Cleveland Indians sold for $8 million in August 1966 as described above, which means at least in the eyes of its new owner, Cleveland was an even better investment than the Cincinnati Reds. But it was the Reds’ management that understood what it took to nurture that investment.

CONCLUSION

In this document we used the tools of sabermetrics, particularly Wins Above Replacement (WAR), to ex amine two trades that are regarded as two of the worst ever: Cleveland’s trade of Rocky Colavito for Harvey Kuenn in 1960 and Cincinnati’s trade of Frank Robin son for Milt Pappas and others in 1966. Both trades triggered significant blowback from their fan bases at the time, but the eventual impact on both teams was quite different.

Colavito for Kuenn: This trade deserves the scorn heaped upon it, but more for the second trade than the first. The first cost the Indians 3.5 games annually over the five years of its life. In a desperate attempt to undo the damage, Cleveland brought Colavito back in an even worse trade that cost the team 6.5 victories annually over six years and even more thereafter.

Robinson for Pappas et al: The fan base scorned this deal as well. Frank Robinson did turn in some Hall of Fame worthy seasons in his six years with Baltimore, but the cost to the Reds was mitigated to a large degree be cause they received enough talent in return to limit the loss to less than two victories annually for six years.

After the first Colavito trade, the Indians fell into a slump that lasted 35 years. Cincinnati rebounded within four years of the Robinson trade to establish a legendary team in terms of the Big Red Machine. It is tempting to attribute this to the differing outcomes of these two series of trades. But they alone are not sufficient to explain the divergent outcome of these two teams.

What explains this outcome better are the different paths chosen by the teams’ senior leadership. Money troubles, actual and imagined, prompted Cleveland’s ownership to direct management to systematically dis-invest in what had been a productive farm system. Cincinnati’s ownership and management worked together to protect, then enhance, their player development system. This difference can easily account for 16-18 wins annually over multiple years, or the difference between Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine and decades of frustration in Cleveland.

Baseball has changed a lot since the 1960s, with more expansion, free agency and multiple layers of postseason playoffs, but a fundamental truth remains. The surest path to sustained success is a foundation built on players you sign, develop, and advance. Few have been better at it in recent years than the Cleveland Guardians.

WILLIAM SHKURTI (“Bill”) is retired after serving twenty years as the Chief Financial Officer for Ohio State University. He holds a BA in Economics and a Masters in Public Policy from that institution. He has written several books and articles about Ohio history. He is a Vietnam veteran and a lifelong (and long-suffering) Cleveland Guardians fan.

Notes

1. Terry Pluto, The Curse of Rocky Colavito (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994).

2. For more about Lane’s stormy tenure in Cleveland see Warren Corbett, “Frank Lane,” SABR Biography Project, accessed October 17, 2022. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/frank-lane-2.

3. For a good description of Colavito’s rise and the fans’ growing attachment to him see Pluto, 39-42.

4. David Nemec and Scott Flatow, Great Baseball Feats, Facts, Figures (New York: Penguin Books, 2008), 258.

5. Hal Lebovitz, “Swaps Leave Fearless Frankie on Spot,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1960, 3.

6. These figures posted online as of March 23, 2023.

7. Warren Corbett, “Gabe Paul,” SABR Bio Project, accessed October 18, 2022. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/gabe-paul.

8. David Bohmer, Cleveland Guardians team ownership history, SABR Team Ownership Project, accessed October 18, 2022. https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/cleveland-guardians-team-ownership-history.

9. Rob Neyer, Rob Neyer’s Book of Baseball Blunders (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006),140.

10. William Schneider, “Frank Robinson and the Trade that Ignited Two(!) Dynasties,” The National Pastime: A Bird’s Eye View of Baltimore (Phoenix, SABR, 2020). Online version accessed October 18, 2022. https://sabr.org/journal/article/frank-robinson-and-the-trade-that-ignited-two-dynasties.

11. “Franchise Page” at Baseball-reference.com and Bohmer.

12. Bohmer.

13. Hal Lebovitz, “Tribe Fans Whoop Over New Chief Lane,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1957, 3.

14. Bohmer.

15. Bohmer.

16. Pluto, 189-90.

17. Mark Armour, “Bob Howsam,” SABR Bio Project. Accessed October 23, 2022. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bob-howsam.

18. Bohmer.

19. Bohmer.

20. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, CPI Inflation Calculator, accessed Octo ber 24, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

21. Bohmer.

22. Jack Torry, Endless Summers: The Fall and Rise of the Cleveland Indians (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1995), 70, 94.

23. Torry, 103.

24. Bohmer.

25. Torry, 69, 93.

26. Bohmer.

27. “DeWitt Sold Reds to 13-member Cincinnati Group,” Official 1967 Baseball Guide, (St. Louis, Sporting News,1967), 172-73.