Two days in August 1971: Tom Seaver and Dave Roberts

This article was written by Scott Schleifstein

This article was published in Fall 2012 Baseball Research Journal

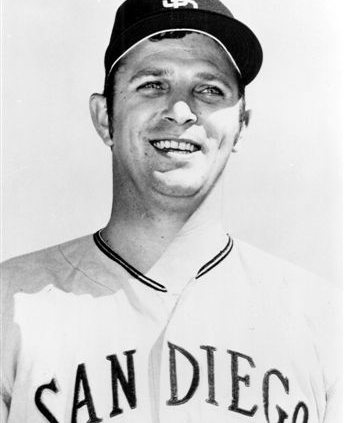

For two days in the summer of 1971, Tom Seaver dueled with another dominant hurler, splitting the games by scores of 1–0 and 2–1. Red Foley, writing for the Daily News, rhapsodized about this matchup, comparing it favorably to legendary contests between Dizzy Dean and Carl Hubbell, Mort Cooper and Whit Wyatt, and Christy Mathewson and Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown.1 The interesting part is Seaver’s competition. His foil wasn’t a fellow Hall-of-Famer like Fergie Jenkins, Bob Gibson, or Steve Carlton. Who was it? Dave Roberts, southpaw for the San Diego Padres. Which naturally leads to the question: Just who was Dave Roberts?2

Roberts logged 13 seasons pitching for the Padres, Houston Astros, Pittsburgh Pirates, Chicago Cubs, Detroit Tigers, Seattle Mariners, San Francisco Giants, and the Mets. Martin Abramowitz, the baseball historian behind the website jewishmajorleaguers.org, teasingly paid homage to the well-traveled pitcher with the “Dave Roberts Wandering Jew Award.”3

1971 was a breakout year for Roberts, as he posted 14 wins, 14 complete games, and a microscopic 2.10 ERA for the lowly San Diego Padres. The Padres’ relative ineptitude makes Roberts’s accomplishments all the more impressive. Founded a mere two years before, when the National League expanded to 12 teams and was split into East and West Divisions, San Diego would struggle to win 61 games in 1971.4 When the curtain mercifully fell on their season on September 30, the Padres were 28.5 games behind the NL West division winners, the San Francisco Giants, and 17.5 games in back of the Houston Astros and Cincinnati Reds, who tied for fourth place. The Padres were mired in the basement of the NL West, not even in “shouting distance” of fifth place. Only the Cleveland Indians had a poorer campaign in 1971, winning 60 games and finishing an eye-popping 43 games out. The Padres would not escape the NL West cellar until 1975, with a fourth-place finish, and would not crack .500 for a season until 1978 (finishing fourth again). Compare that to the Expos, who approached respectability sooner, winning 73 games in 1970 and, in 1979, finishing 95–65, a mere two games behind the eventual World Series champions, the Pittsburgh Pirates.5

San Diego scored a paltry 3.02 runs per game, which was the worst in either league in 1971. To put this figure into perspective, the eventual-champion Pirates averaged 4.86 runs per game, and the NL average was 3.91. The Padres totaled only 486 runs, the lowest in major league baseball. Pittsburgh scored an astounding 302 more times than San Diego! The team batting average was .233, tied with the NL East cellar-dwellers, the Philadelphia Phillies. Only three AL clubs were worse. Some of the other “offensive” (pun intended) vital signs were only slightly better—the .293 on-base percentage was only the worst in the NL (the AL’s California Angels finished last in this category with a .290 OBP); their .332 slugging percentage was also only the worst in the NL (but here, three American League squads—Milwaukee, California, and Washington—were less successful than San Diego with slugging percentages of .329, .329, and .326, respectively). If the 1960’s Los Angeles Dodgers had a “pop gun” offense, the ’71 Padres’ offense could perhaps be characterized as a water pistol.

The lack of run support for Roberts was epitomized in the Padres’ July 3 encounter with LA. Roberts lost to Al Downing, 1–0, with both pitchers tossing a complete-game six-hitter. The Dodgers made their hits count, manufacturing a run in the top of the ninth with a Joe Ferguson single, a sacrifice bunt by Downing, and Willie Davis doubling home pinch-runner Bill Russell. The Padres’ best chance to score was in the bottom of the sixth, when two singles (including one by Roberts who was 2-for-2 on the day) went for naught due to an Enzo Hernández force-out and a fly out by Leron Lee. During 1971, Roberts would repeatedly play the role of “hard-luck loser.” Other instances were May 17 at Houston (four hits, three of them singles, in a 2–0 defeat at the hands of Don Wilson), May 31 vs. Philadelphia (five hits, all singles except for a double by Roberts, in a 3–1 loss to Jim Bunning), and June 16 at Montreal (a one hitter by Bill Stoneman for a 2–0 loss).

Things didn’t go much better when the Padres were in the field. Only the Giants made more errors (179 to 161) or had a lower fielding percentage (.974 to .972). To put these numbers in context, the Cincinnati Reds led Major League Baseball with a fielding percentage of .984, while committing only 103 errors. Unlike the power-packed Giants with blue-chip hitters like Hall of Famers Willie McCovey and Willie Mays (albeit near the end of his career) and perennial All-Star Bobby Bonds, San Diego’s virtually non-existent offense couldn’t compensate for its numerous defensive lapses. Shortstop Enzo Hernández would tie Giants shortstop Chris Speier for the most errors in MLB, with a total of 33. Hernández’s sometime double-play partner, Don Mason, committed 15 errors in 90 games at second base. Compare this to the statistics of the NL Gold Glove winners, the Mets’ Buddy Harrelson at shortstop (16 errors) and the Reds’ Tommy Helms at second (9 errors), and you begin to get a sense of some of the challenges faced by Roberts. Interestingly, notwithstanding Harrelson’s contributions on defense, only Seaver’s Mets in the NL turned fewer double plays than the Padres (144 to 135); on both coasts, the pitcher was forsaken by his proverbial “best friend.” For a control pitcher like Dave Roberts who relied on his sinkerball and had only 135 strikeouts (as compared to Seaver’s 289, tops in the NL), the erratic fielding surely had a devastating effect.

Consider, for example, Roberts’s start at San Francisco on June 20. He went head-to-head with the Giants’ Steve Stone, eventually losing 2–0. San Francisco’s breakthrough came in the bottom of the fourth inning when Roberts himself and right fielder Ollie Brown both committed errors during the same play—Roberts’s attempt to pick outfielder Ken Henderson off first base. The defensive blunders were costly as Henderson came around to score on the play. Given that Henderson reached base via walk, the Giants managed to score a run and take the lead, en route to sweeping both ends of a doubleheader, without the benefit of a single hit in the inning. Also illustrative is Roberts’s August 29 outing in Montreal, where two errors by Hernández and another error by Mason in a disastrous second inning would lead to five Montreal runs against Roberts, four of which were unearned. Roberts was lifted by Padres manager Preston Gomez after 12⁄3 innings of work, with San Diego eventually losing 6–1.

The Padres bullpen did a credible though unspectacular job for Roberts. On July 9 against the Cubs, Bob Miller preserved a 1–0 win for Roberts by inducing power hitter Jim Hickman to hit into a game-ending double play. On June 25, Dick Kelley recorded a save with Roberts getting the “W,” by retiring LA’s Bobby Valentine, Duke Sims, and pinch-hitter Bobby Darwin in order in the bottom of the ninth.

Things didn’t always go as planned, though. On April 19, Roberts left the game against Los Angeles in the top of the eighth with men on first and second and no one out; San Diego held a 2–1 lead when Al Severinsen replaced Roberts on the mound. After a successful sacrifice bunt by Dick Allen (yes, the slugger Dick Allen, how’s that for managing?) and an intentional walk to Bill Sudakis, infielder Billy Grabarkewitz doubled off Severinsen, driving in two runs. This would prove to be the difference in the contest, which LA won, 3–2. Another case in point, going into the top of the seventh on June 29, the Padres and Giants were knotted at three. After retiring the first batter, Roberts yielded back-to-back singles. Roberts was removed; Miller came on in relief. An error by third baseman Ed Spiezio on Willie Mays’s ground-ball followed by a clutch single by Bobby Bonds resulted in two runs for San Francisco. The Giants went on to win the game, 6–4.

Game 1: August 11 at San Diego

Over the first three innings, the Mets and Padres combined for three singles. One by Padres center fielder Larry Stahl in the bottom of the first; one by Mets left fielder Cleon Jones in the top of the second; and one by Roberts himself in the bottom of the third. None of the runners reached second base. Seaver recorded three strikeouts, Roberts two.

The stalemate continued through the middle three frames. The Mets offense consisted of a Don Hahn single in the fourth inning (Hahn would be stranded at second after a successful Wayne Garrett bunt) and a walk to Bob Aspromonte in the fifth (erased by a double-play groundball to second baseman Dave Campbell). The Padres accomplished even less, with Seaver showing his Cy Young form. San Diego only managed a Nate Colbert walk in the fourth, which was rendered meaningless as Seaver recorded all three outs via strikeout. After six innings, Seaver had fanned nine in total.

The drama continued to build as the game headed toward its conclusion. Donn Clendenon led off the eighth inning for the Mets with a single and advanced to second on a Bob Aspromonte bunt. Nothing came of the scoring opportunity when Jerry Grote lined into an inning-ending double play to Stahl in center field. According to Murray Chass’s game recap in The New York Times, the Mets’ “best scoring opportunity” against Roberts was defused when Stahl snared Grote’s sinking line drive, robbing him of a “certain hit.”6 Clendenon, assuming that Stahl couldn’t make the play, had already reached third base when Stahl made the catch, resulting in an easy 8–4 double play. Phil Collier of the San Diego Union concurred with Chass’s analysis, noting that but for Stahl’s “miraculous catch,” Seaver would have been a 1–0 victor.7

Buddy Harrelson drew a walk to start the ninth, but Seaver ended the nascent rally by hitting into a 6–4–3 double play. Maybe the double play was Roberts’s friend after all; all told the Padres would turn five of them in the game. Meanwhile, Tom Terrific continued to stonewall the Padres, adding five more strikeouts to his total, thereby keeping pace with Fergie Jenkins for the NL lead.8 Perhaps the Padres’ best threat came in the bottom of the ninth when Stahl worked a two-out walk, bringing Nate Colbert—San Diego’s lone All-Star (who, by the way, the Mets were interested in acquiring in exchange for Mike Jorgensen, Tim Foli, and a “stack of cash”9)—to the plate. Seaver struck out Colbert, sending the game to extra innings.

The Mets had their chances against Roberts in the top of the 10th and 11th innings. In the 10th, the Mets couldn’t push across any runs despite having men on first and second with only one out. Roberts came up with a clutch strikeout of Clendenon; then, Tim Foli grounded out to end the inning. The 11th saw Ken Singleton (pinch-hitting for Seaver) and Hahn single consecutively with two outs, but Roberts got Wayne Garrett to ground out back to the box and Roberts had wriggled out of the jam.

San Diego didn’t make any headway either. Seaver cruised through the 10th, retiring the Padres in order. (Playing “Monday morning quarterback,” one wonders why Mets manager Gil Hodges opted to pinch-hit for the still dominant Seaver with two outs in the top of the 11th.) Hodges called in Danny Frisella to relieve. After a Bob Barton single, Frisella struck out Roberts and pinch-hitter Angel Bravo. The game lumbered into the 12th inning: the crowd of a little under 11,000 people was getting their money’s worth.

Roberts continued to stymie the Mets in the 12th as a double-play grounder from Donn Clendenon negated Cleon Jones’ one-out single.

The bottom of the 12th saw the game abruptly end. Stahl touched Frisella for a lead-off double. The slugging Colbert was walked intentionally. The following batter, Leron Lee, bunted Frisella’s first offering foul. As Lee tried to bunt the next pitch but missed, Stahl and Colbert broke for third base and second base respectively. Grote then threw to third to try to cut down Stahl. Grote’s throw deflected off Garrett’s glove and landed in left field. Jones’s throw home came too late as Stahl had already crossed the plate.

Although Seaver clearly had outpitched Roberts, Roberts got the win; another example of the cruel inequities of baseball. Seaver allowed only three hits (all singles) and walked two, while recording 14 strikeouts. Roberts had a less dominant but still very respectable outing, giving up seven hits, issuing three walks, and striking out seven.

Padres skipper Preston Gomez called it “the best game that we’ve [the Padres] ever played,”10 which was probably not an exaggeration given the futility that marked the Padres’ short and unremarkable history to date. Gomez added, “Roberts and Seaver were both great and Stahl was the difference—with his glove, his bat and his baserunning.”11 Mets manager Hodges allowed that Roberts had pitched “a beautiful game.”12 But perhaps the most poignant postgame comments were provided by Roberts and Seaver themselves. Roberts generously said of his counterpart: “I have nothing against Frisella, but I’m glad Seaver didn’t get the loss. He pitched too well to lose.”13 Seaver, ever the class act, complimented Roberts in kind: “His record shows that he has gone out there every fourth or fifth day and pitched well—that is as much as you can expect of anyone.”14,15 Given the Mets’ struggles to consistently score runs for him, Seaver’s comment transcends good sportsmanship and evinces a certain amount of empathy for Robertss’ plight.16

Game 2: August 21 at New York

In stark contrast to almost all sequels (remember Staying Alive, the 1983 follow-up to Saturday Night Fever? How about 1998’s Blues Brothers 2000?), Roberts-Seaver II actually was on a par with the original. The game drew a somewhat disappointing attendance of a little over 26,500.17

For the first three innings, Roberts retired the Mets in order. Meanwhile, San Diego touched Seaver for three singles. Two of them came in the top of the second, but the fire was doused when Larry Stahl—the hero of the earlier contest—hit into a 6–4–3 double play.

Roberts continued to coast through the next three frames, yielding only a base on balls to Jones and a single to Clendenon with two outs in the home fourth. The Padres seemed on the verge of solving Seaver in the fifth. According to Phil Collier’s write-up in the San Diego Union, Agee made a fine defensive play in center field to corral Ollie Brown’s “prodigious” lead-off liner.18 The Padres then grabbed a 1–0 lead on a solo homer by third baseman Ed Spiezio. After retiring Barton on a groundball to short for the second out, Roberts and the light-hitting Enzo Hernández (career average: .224) both singled. Seaver’s strength as a pitcher can perhaps be found in how he bore down to strike out Don Mason to end the inning. Although the Padres “hit him hard” according to Bob Barton and Seaver, by his own admission, had “his worst stuff since the All-Star break,”19 Seaver got the man that counted. The floodgates didn’t open. After the fifth inning, the Padres would not register another hit off Seaver for the remainder of the contest. The only blemishes for Seaver thereafter were walks to Hernández in the eighth inning and to Stahl in the ninth (with Stahl stealing second base).

The game was another nail-biter, as Roberts was clearly in control, handling the Mets with relative ease with one major exception—Cleon Jones, who was responsible for two of the Mets’ total of three hits in the game. Jones led off the home seventh with a triple, scoring on Tommie Agee’s sacrifice fly to tie the game at one. Joseph Durso, writing in The New York Times, dubbed it a “charity triple”;20 like fellow columnists Foley of the New York Daily News and Collier of the San Diego Union, Durso characterized the handling of the defensive chance by center fielder Cito Gaston and right fielder Ollie Brown as an “Alphonse and Gaston” play (riffing on the center fielder’s name for a delicious—or atrocious?—pun). Both outfielders tracked Jones’s shot. Fearing an imminent collision, with neither Gaston nor Brown calling for the ball, both veered off at the last moment and the ball fell between them for a safety. Apparently, the gaffe didn’t faze Brown, who almost threw Jones out at home on Agee’s fly ball on the very next defensive chance. Then, with two outs in the bottom of the ninth, Jones clubbed a walk-off home run to give the Mets the win. And, just like that, the game was over. The homer by Jones—which according to the account in the Union “struck the top of the fence”21 in right-center field and then went over—was something of an anomaly as Roberts yielded a league-best .3 homers per nine innings in 1971.22

Now Roberts was again in the familiar position of the “hard-luck loser,” making the August 21 contest something of a mirror image of the August 11 game in San Diego. This time around, Roberts’s statistics are marginally better than those compiled by Seaver. Roberts yielded half as many hits as Seaver (6–3) and one fewer walk (2–1), while striking out only one fewer batter than his mound rival (8–7).

To continue the analogy, where Roberts reaped the benefits of solid fielding in the earlier contest, the edge in fielding this time around clearly went to Seaver. The costly Gaston-Brown defensive blunder must have made Stahl’s catch seem like a distant, dim memory to Roberts. In contrast, according to the various news-paper accounts of the game, the Mets’ defenders turned in a string of stellar plays, “picking up” Seaver. In addition to Tommie Agee’s catch on the ball hit by Ollie Brown in the fifth frame, third baseman Bob Aspromonte speared Enzo Hernández’s liner in the top of the first and right fielder Ken Singleton leaped to make a one-handed grab of Ollie Brown’s “rifle shot” in the seventh.23 Perhaps most significantly, Mets outfielders would quell a potential rally in the ninth. Singleton would come up with two more defensive gems, first snaring a Nate Colbert liner and then an Ed Spiezio fly ball. Sandwiched between Singleton’s exploits, Jones made a fine catch of his own in robbing Brown of an extra-base hit which likely would have scored Stahl to give San Diego a 2–1 lead: if Larry Stahl was the difference between victory and defeat in game one (at least according to Preston Gomez), then Cleon Jones was the difference in game two.

It seems fair at this juncture to second-guess Gomez in allowing Roberts to face Jones in the bottom of the ninth. After all, in addition to his “charity triple” and homer in this game, Jones had gone 2-for-4 against Roberts on August 11 for a total of 4-for-7 in the two games. While it contradicts conventional baseball wisdom to put the winning run on base, Roberts appeared to be in control and had a considerably easier time with the on-deck hitter Donn Clendenon, with Clendenon going only 2-for-8 against Roberts on August 11 and 21, while whiffing four times (including in the seventh of the same game right after Jones’s three-base hit). By way of recent precedent, in the earlier game in San Diego, Roberts had issued Jones an intentional walk rather than having him hit with one out and a man on second in the 10th inning; Roberts took his chances with Clendenon instead, striking him out. Perhaps more tellingly, in the 12th inning of the earlier game, after a single by Jones, Roberts induced Clendenon to hit into a double play.

Both Seaver and Roberts displayed refreshing honesty, humility, and professionalism in reviewing their respective performances. Conspicuous was the absence of the chest-pounding and brashness so often heard from athletes today. In addition to noting that he did not pitch particularly well, Seaver admitted that his efforts were aided by a combination of luck and good plays in the field. Roberts believed he had the best command of his pitches all season. Focusing on Jones’ fateful, final at-bat, Roberts credited Jones for hitting a “good” slider on the inside corner. More philosophically, Roberts also noted that “a couple of inches this way and it’s [Jones’s fly ball home run] in the park. I guess that’s what makes the game fascinating.”24,25

Roberts and Seaver would clash again several times over the course of their careers, but in 1971 both hurlers were perhaps at their most dominant. Almost exactly one year later on August 22, 1972, Seaver’s Mets would defeat Roberts’s Houston Astros 4–2 (Roberts was traded to Houston in the 1971 offseason for pitchers Bill Greif and Mark Schaeffer as well as infielder/outfielder Derrel Thomas) at Shea Stadium; on June 1, 1974, Seaver would outduel Roberts again when the Mets beat Houston 3–1, with both tossing complete games.

Dave Roberts’s moments of glory—and, much more importantly, his grace, class and dignity in the face of both victory and defeat—are well worth remembering.

When not indulging his interest in (obsession with?) baseball in the 1970s, SCOTT A. SCHLEIFSTEIN practices promotion marketing/trademark law in New York City. As a life-long Yankees fan, Scott hastens to add that he is a fan of only the pitcher Dave Roberts.

Author’s note

Ethnic pride first drew me to Dave Roberts. In the course of researching and writing my first SABR article (“A Small, Yet Momentous Gesture,” Baseball Research Journal #34, 2005, discussing the decision by Oakland A’s players Ken Holtzman, Mike Epstein, and Reggie Jackson to wear a black armband on their uniforms September 6, 1972 out of respect for the Israeli athletes murdered at the Olympic Games in Munich), I vaguely recalled Roberts as being a Jewish baseball player. A journeyman going pitch for pitch with a baseball legend such as Tom Seaver is, in and of itself, interesting; a Jewish journeyman made the story fascinating and intriguing to me. I saw Roberts’s pitching prowess as a subtle but strong refutation of the anti-semitic canard that Jews are bookish and nonathletic. I later learned that Roberts was the child of a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother who was actually raised by a gentile step-father. Roberts would qualify as Jewish only under Reform Judaism by which one can claim Jewish identity through either parent (Conservative and Orthodox Judaism hold that only matrilineal descent is valid or “kosher,” if you will). Moreover, Roberts apparently never acknowledged any connection to Judaism. In fact, in a San Diego Padres press release dated June 5, 1970, Roberts credits praying with his younger brother (who was studying to be a minister in the Greek Orthodox church) as helping him recover from a career-threatening injury to his pitching shoulder; Roberts made the same point in discussing his comeback in the Houston Chronicle.30 His David and Goliath tale remained intriguing to me, nonetheless.

Notes

1. “Cleon Homers Padres, 2–1 for Seaver,” New York Daily News, August 22, 1971.

2. This question is trickier than it may seem at first glance as the annals of Major League Baseball contain numerous players named Dave Roberts. Of the four Dave Roberts, perhaps the most famous (or infamous, depending on your favorite team) is the outfielder David Ray Roberts whose stolen base in the 2004 American League Championship Series was pivotal to the Red Sox historic comeback against the Yankees which would culminate in their first World Series championship since 1918. The Dave Roberts addressed in this article is David Arthur Roberts. See baseball-reference.com.

3. Burton A. Boxerman and Benita W. Boxerman, Jews in Baseball: Volume 2, The Post-Greenberg Years, 1949–2008 (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2010).

4. The other NL expansion team was the Montreal Expos.

5. Oddly enough, Dave Roberts was a member of the 1979 world champion Pirates. The Pirates acquired him midseason from the San Francisco Giants in the same trade that brought the All-Star and batting champion Bill “Mad Dog” Madlock to the club.

6. “Padres Top Mets on Grote’s Error in 12th Inning, 1–0,” The New York Times, August 12, 1971.

7. “Roberts Hurls 12-Inning Shutout in Outdueling Mets’ Seaver, 1–0,” San Diego Union, August 12, 1971.

8. At season’s end, Seaver would lead the National League in strikeouts, besting Jenkins (the National League’s Cy Young Award winner in 1971) 289–263. Still, Seaver had fewer strikeouts than Detroit’s Mickey Lolich (308) or Oakland’s Vida Blue (301); Blue won both the American League’s Cy Young and MVP Awards in 1971.

9. “Mets Beat Padres, 2–1, on Homer by Jones in Ninth,” by Joseph Durso, The New York Times, August 22, 1971.

10. “Roberts Hurls 12-Inning Shutout in Outdueling Mets’ Seaver, 1–0,” see note 9.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. 10–12, with an ERA of 2.09, including the August 11 victory against the Mets.

15. “Roberts Hurls 12-Inning Shutout in Outdueling Mets’ Seaver, 1–0,” see note 9.

16. Throughout his Mets career, Seaver often experienced this kind of deflating result. For example, in 1971, Seaver suffered a dispiriting pair of complete game losses to the Astros in Houston. The first by the score of 3–1 on May 1; the second, a 2–1 defeat on July 17.

17. In comparison, Saturday contests against Atlanta (on May 22) and Chicago (on July 31) at Shea Stadium had attendance of approximately 43,700 and 43,900 respectively.

18. “Seaver Admits He’s Lucky as Mets Shade Roberts,” San Diego Union, August 22, 1971.

19. Ibid.

20. “Mets Beat Padres, 2–1, on Homer by Jones in Ninth,” see note 9.

21. “Seaver Admits He’s Lucky as Mets Shade Roberts,” see note 18.

22. By way of context, Tom Seaver gave up .6 home runs per nine innings in 1971. The statistics for Fergie Jenkins (the 1971 National League Cy Young Award winner), Vida Blue, and Bart Johnson (1971’s American League Leader) are, respectively: .8, .5 and .455.

23. “Seaver Admits He’s Lucky as Mets Shade Roberts,” see note 18.

24. “Mets Beat Padres, 2–1, on Homer by Jones in Ninth,” see note 9.

25. Press Release and John Wilson, “Inside Dave Roberts’ Battle to Escape Oblivion,” Houston Chronicle, included in Dave Roberts’s Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.