Under Coogan’s Bluff

This article was written by Harry Turtledove

This article was published in The National Pastime: The Future According to Baseball (2021)

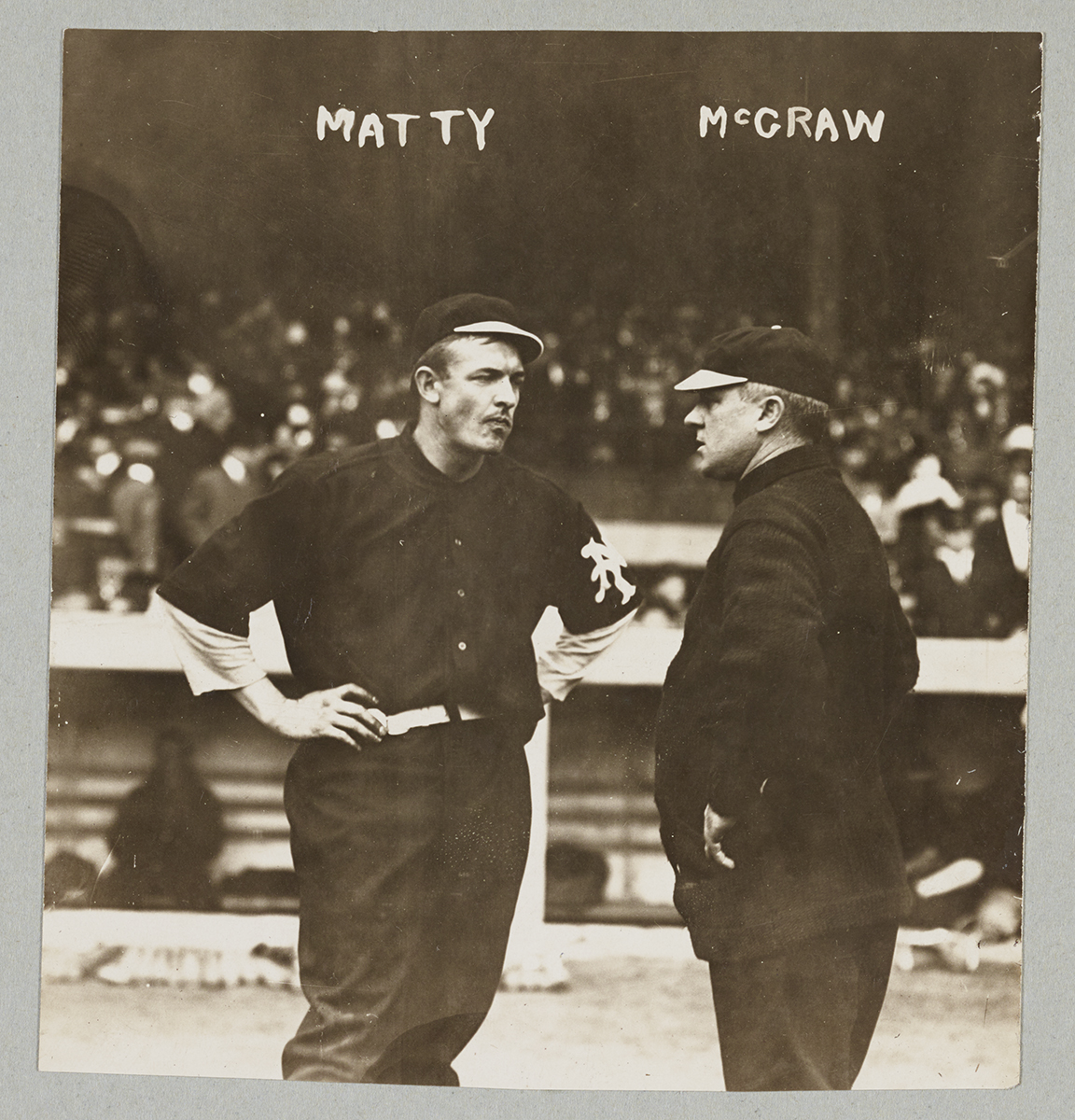

New York Giants stalwarts Christy Mathewson and John McGraw. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

They open the door. They’re opening thirty doors at once, but I can only talk about mine. Air from 2040 goes out, and air from 1905 comes in. The first thing I do is cough. It smells like horseshit and coal smoke and a locker room after an Atlanta double-header. In 1905, New York City only — only! — has 4,000,00 people, but I don’t think any of ’em took a bath in the past week.

I figure it’ll be cold in the portal building, but it isn’t. It’s always 72 inside the portal itself, and the 1905 air in the foyer feels about the same. I step out into the past. To either side of me, the other Angels do the same. We’re all in slacks and jackets, shirts and ties. We’ll still look funny to the locals, but less than if we wore our usual 2040 clothes.

On the street, the men are in workmen’s clothes or gloomy wool suits with too many buttons and tiny lapels. Some wear cloth caps, others derbies. The women… It’s sad. Skirts down to the ground, blouses and jackets that cover the rest of ’em, hats like you wouldn’t believe.

A white-bearded guy stumps by the front window. I mean stumps — he’s got a peg leg like you’d see in a pirate movie. Keyshawn Fredericks, who’ll pitch for us tomorrow, stares. “Whoa!” he says. “I bet he fought in the Civil War!”

He’s probably right. Where we are, when we are, smacks me in the face like a giant salmon. Guys who’ve done this before told me how it is. But living it. The difference between hearing it and living it is like the one between a picture of a steak dinner and eating a steak dinner.

Eddie Morales gets out in front of us. He’s the manager; it’s his job. “Three o’clock local time,” he reminds us. “The buses’ll be here any minute to take us to the hotel. We’ll have dinner, get as much rest as we can, and then head for the Polo Grounds. We’ve got another game to win. Been a hell of a long year, but this one’ll give us something to brag about.”

We have to stand around for ten minutes before the buses show up. Yeah, plural — they have six-horse teams. Carriages, wagons, men on bikes, a few cars. Traffic in 1905 isn’t the same as it will be two lifetimes on, but there’s a lot of it.

We go out through the big open doors and climb on the buses. They’re painted on the sides — LOS ANGELES ANGELS, 2040 CHAMPIONS. People will know who we are anyway, from our clothes and because we average a lot bigger than they did in 1905. Somebody yells, “Matty’ll clock you clowns!” A big cheer goes up.

They yell other things, too. We got warned about that, and it’s true. It’ll be worse — louder, anyway — tomorrow at the Polo Grounds. That word we don’t say now? They scream it. Keyshawn and three or four other guys are African American, and Thabo’s from South Africa. They probably think he’s from South Carolina. They yell at him like he is.

Some of our Latinx players are dark, too — Adilson Bivar, especially. He’s from Sao Paulo, where a lot of the fireballers around the league are from. He takes the crap in stride. If we have a lead tomorrow, he’ll close.

The crowd doesn’t know what to make of Kaz Fukushima or Pong-ju Pak. They call them Chinamen or something like that but worse. Japan? Korea? Not on their radar, not that they have radar.

Kees was born in Amsterdam, and Ralph’s from Melbourne. The downtime people can’t tell that by looking, though, so they just hoot at them for being from 2040.

The buses start rolling, heading uptown. When traffic’s easy, we go a little faster than a walk. When it’s heavy, we move a lot slower. No traffic lights. Cops at big intersections. At the others? We’re on our own. Fun!

Keyshawn and I sit next to each other. He stares out the window. “It’s so white, man!” he says, and he’s not talking about the smoky air or the sootstained buildings. “So white. My people, they’re still down South picking cotton, I guess. Not slaves, but they might as well be.”

“My own great-great-greats come through Ellis Island about now,” I answer. “They finally see one Russian pogrom too many.”

“One what?”

“Race riot. Or religion riot. Whatever. 1905 Russians like Jews the way 1905 Southerners like black folks.”

He nods. “Gotcha.”

We go up Central Park West. Central Park looks like… Central Park. I’ve been there when we play the Yankees. Only big difference is what people wear.

When we go past 72nd, Keyshawn points to the fancy building on the west side of the street. “That’s the Dakota.”

I know what the Dakota is. “John Lennon lived there.”

“Yeah, him, too,” Keyshawn says. I look at him. He looks back at me. “Time and Again, man.” I saw some of the Netflarx stream, but Keyshawn reads science fiction. Old science fiction, even. What do you expect from a left-hander?

In Harlem I think I hear Spanish, but it’s Italian. The hole-in-the-wall shops and restaurants don’t look too different from how they will 135 years on — minus the LEDs and neon — and like Keyshawn said, everyone’s White.

We stop in front of the Mount Morris Hotel. We hop down from the buses, kinda stretch, and go inside to check in. The lights are electric, but dim.

The room. Bed’s okay, I guess. A glass and a basin and a pitcher on the dresser. Toilet? Bathtub? End of the hall. Line forms on the left!

No WiFi. No TV. No radio. Not even a landline. All we can bring back is our clothes, a change or two, and our uniforms. They superscan us before we enter the portal, same as at airports.

Gym? Weight room? Nope. The Giants won the toss. We came back. They didn’t come forward. When we play ’em, it’s by their rules. We make money off it. So do they. They think it’s a lot. Well, to them it is. And there’s the whole pride thing, on both sides of the time gap.

If we don’t die of boredom before we play. What do people do in hotel rooms like this? Chances are they go out and drink and screw. We can’t even do that. Or we’re not supposed to. That guy on the 2038 Orioles in 1909 Pittsburgh. No, no names. But they monitor us closer now.

Coaches bang on our doors at six. We troop down to the dining room. Nutrition isn’t everything it should be. But roast chicken, peas, and a baked potato. That’s not too bad. The bird’s even tasty. And one bottle of beer. Budweiser. Some things don’t change. Yeah, it tastes the way it’s supposed to.

Then back to our rooms. The coaches keep an eye on us. What else are coaches for?

I look out the window. It looks dark. Street lights aren’t everything they’re gonna be. I lie down on the bed and stare at the ceiling. After a while, I doze off. Nothing else to do.

I wake up an hour later. Down on the street, an oompah band — trumpets and tubas and bass drums — is playing as loud as it can. They warned us this kind of crap happens. Here-and-now people help the Giants however they can. If the guys from 2040 don’t get any shuteye, maybe they won’t play so good.

Uptime, we’d call the police. Here? Now? Half the chavs in that horrible band’re probably New York’s finest.

Eventually, they shut up and go away. Even more eventually, I fall asleep again. Two hours later, they come back. Sweet night, uh-huh.

* * *

Breakfast? Bacon, eggs fried in bacon grease, hash browns. Horrible for you, but it tastes good. Lots of coffee. We need coffee.

We board the buses again and head for the Polo Grounds. Eighth Avenue and 157th, across the river from where Yankee Stadium’ll be. Not this one, the one before. Only that one’s not there yet, either.

They haven’t started letting fans in, but there’s already a crowd up on Coogan’s Bluff waiting to watch for nothing. They boo us when they spy the buses. Keyshawn waves, just to rile them up some more. We go on in. The visitors’ locker room isn’t big enough to swing a cat. We jostle each other when we put on our unis.

Then we get our gear. The catcher’s masks are okay. The wire’s strong, and they even come down to protect the throat. No helmets to wear underneath, though, or at the plate. The catcher’s mitts are thick leather pancakes. No shinguards, dammit; Kaz shakes his head. Balloon protectors.

First baseman’s mitts are longer, flatter versions of what the catchers use. Fielders’ gloves? They’re gloves, like a soccer ’keeper wears, only with baby webs between the thumb and first finger.

A bunch of bats to choose from. Louisville Sluggers, different lengths and weights, but all heavy and thick-handled. “Never get any whip with these sorry things,” Mel Sturgeon grumbles. He hit 48 out this season, so he knows about whip.

“Just square it up. It’ll do what it does. That goes for everybody,” Eddie says, raising his voice a skosh. “Ball won’t jump, either. Did you look? Nobody on the Giants hit more than seven. Nobody in the Show even got into double figures.”

They’re little guys. They don’t know about launch angle. Even so, there’s a difference between seven and 48. Just a bit.

We go out to loosen up, get used to the 1905 equipment. My great-grandpa went to the Polo Grounds in the 1960s, when the Mets were new. He told me about it. This park is the one before that, though. It’s wood, with Y-shaped pillars every fifteen feet or so holding up the roof over the second deck. No fence in center field, just white posts holding up a waist-high rope or wire. People in carriages or cars can watch the game. They won’t see well — has to be 500 feet out there. Real short down both lines, though, same as in the park my great-grandpa saw.

The Giants are warming up, too. They eye us. We eye them. They’re wearing their Series uniforms, black with white caps and socks and a big white NY on the chest. Baggy wool flannel, but classy anyway. No numbers — nobody’s thought of those yet.

They look like they know what they’re doing. Well, they should. They went 105-48, then beat the A’s in five in the all-shutout World Series. Mathewson threw three of them. Won’t his arm be dead, facing us a few days later? I hope so.

I start playing catch to get loose. The third time Dave Bowyer, our third baseman, throws me the ball, I drop it. Never would with the glove I’m used to, but these tiny little things from 1905 give you no margin for error.

Eddie sees me do it. “Two hands, guys!” he yells. “Remember, two hands! Gotta make the plays!”

I feel like a jerk. And I feel even lousier when the Giants’ manager snickers at me. John McGraw — I looked him up online. Little stumpy guy; looks mean. He’s only thirty-two, so he might still play, but he’s put on weight.

The umps watch both teams warm up. Only two, not the six we’d have at a postseason game. No automated strike zone. No replay, either. Whatever they call, everybody’s stuck with it.

When I take grounders, the infield grass seems okay. The dirt… They’ll rake it before we start. Even so, it’s raunchier than anything I’ve played on since Little League. Same with the outfield: bumps and divots everywhere. You’ll get some exciting hops. Yeah, a few.

Look up old-time stats, you’ll see the 1905 Giants fielded .960. You think: Stone hands. That’s what I figured till I went back there. Put on one of those gloves, trot out on that field, and you don’t want to laugh at them any more. You want to tip your hat.

They’ve razzed us nonstop from Coogan’s Bluff since we arrived, but those guys are far enough away, we can pretty much ignore ’em. It gets harder after the stands start filling up. I wonder if any of my great-greats have figured out that baseball is a pretty good game and come uptown to watch. They wouldn’t know I was descended from them; not like Kaplan’s a rare name. It’d be pretty funny if they were here anyway, though. Anybody who isn’t White, the people in the seats scream at him. Some of what they scream. We’ve come a ways since 1905. We aren’t where we ought to be, but we aren’t where we were, either. Thank God.

Ladies? They’re worse than the men, or maybe just shriller.

And some of those people, maybe even screaming so they fit in, are recording the game with little tiny devices the folks from 1905’ll never notice. They’ll go up through the portal again afterwards, just like us. And the FOXSPN techs will stitch the footage together and stream it at a couple of benjamins a pop. Playing against the past is fun. Monetizing it? That’s profit!

Eddie and McGraw exchange lineup cards. The umps go over the ground rules. The PA announcer has a megaphone, not a mike. He bawls out the lineups to the crowd. The Giants take the field. Twenty-five or thirty thousand people scream their heads off.

“Play ball!” Hank O’Day says. He’s working the plate. Jack Sheridan handles the rest of the field.

“Dave Bowyer, third base!” Megaphone Man booms. And it’s a game.

* * *

Dave steps in. I’m hitting second, so I crouch on one knee swinging a bat in the on-deck circle to see what Mathewson’s throwing. Bresnahan, the Giants’ catcher, doesn’t crouch down as far as guys do now. He’s farther behind the plate than they perch now, too. O’Day stands right in back of him, looking over his head, not his inside shoulder.

Mathewson’s first pitch is a batting-practice fast-ball…except it’s right at the knees on the outside corner. Unhittable. “Strike one!” O’Day yells. As soon as Matty has the ball back, he winds up and fires again. This one’s maybe two miles an hour faster, and maybe — maybe — an inch outside. O’Day gives it to him. “Strike two!”

You see right away why he’s so good. Take a little off, put a little on, send it exactly where you want to… Old-timers go on about Greg Maddux. Like that.

Dave leans over the plate a little. Mathewson’s next one’s up and in. Then he hits that outside corner again. Dave gets the bat on it, but dribbles one to second.

“Joshua Kaplan, second base!” the PA man shouts. I step into the left-hand box against a Hall of Famer. Weird.

He throws the first one right at my hipbone. I start to buckle — and it breaks back over the inside corner. O’Day calls it a strike. Well, it is. Bresnahan chuckles as he tosses the ball back to Mathewson. “Never seen a fadeaway before, huh?” he says. Then he says another word, the one Jews like just as well as black people like the one the crowd’s been screeching at Keyshawn.

“We call it a screwball, ya dumb mick shithead,” I answer. I’d never do that in 2040. I know better. If you think we’re messed up now, though, going back in time shows you how we got that way.

People don’t throw the screwball much any more. It tears up your arm. Nobody enjoys microsurgery every couple-three years. But Matty has a good one. Two pitches later, I fly out to center. I think I’ve hit it hard, but it doesn’t go anywhere. Dead ball, yeah.

“Batting third, Mel Sturgeon, left field!”

Mel’s a lefty, too; he’s 6-4, 225. He makes you thoughtful when he digs in, in other words. Mathew-son gives him one low and away, and Mel goes with it. He flips it down the left-field line. Only about 280 there, so it lands in the seats. He trots around the bases with a big grin on his face. We’re up a run.

Matty kicks the dirt once. He waits for them to throw the ball back out of the stands, which they sure don’t in my time. Then he gets Pong-ju to ground to short. In come the Giants. Out we go.

“Roger Bresnahan, catcher!” the PA guy says. The catcher leading off? Okay.

Bresnahan steps in. He stares at Keyshawn. “Watcha got?” he asks, and adds that other word, the one you don’t say in 2040.

Keyshawn fires a fastball, maybe 94, at his belly button. Bresnahan folds up like a clasp knife. Ball one. Bresnahan looks out again. Keyshawn puts a curve on the outside edge. Bresnahan flails. He can’t hit it, any more than you can eat soup with a fork.

And Keyshawn gives him full gas, 99 or so, right at his coconut. I don’t know how Bresnahan falls out of the way, but he does. As he’s picking himself up, a little at a time, Keyshawn says, “You don’t want to call me that again, White boy.”

Bresnahan takes half a step toward him. He stops even before Kaz can get in front of him. He’s 5-9 or so, 190 or 200. He’s giving away ten inches and sixty pounds. He may be a racist so-and-so, but he doesn’t have a death wish.

O’Day also hustles out there. He’s an ump who works hard. Good for him. “Knock it off, both of you,” he says. “Roger, you knew they played Negroes. Get back in the box.” He turns to Keyshawn. “Enough from you, too. You made your point.”

Baseball starts again. The American game, right? Two pitches later, Bresnahan bounces to me. I make sure I watch it into my tiny glove, and I throw him out. The next guy fans. Mike Donlin, who hits third, would be the MVP if they have one in 1905. He gets good wood on a fastball, but lines out to Sturgeon.

We put a guy on in the second — bad-hop single over Art Devlin’s head at third — but don’t do anything with him. They get their first hit in the second, when Bill Dahlen pokes one past me. I just touch it. With a real glove, it’s an out, but not with the toy I’m using. Keyshawn catches Devlin looking to strand Dahlen.

Then Keyshawn hits. No DH in 1905. He looks dangerous up there. Maybe he is, if he makes contact. He doesn’t. Mathewson does: he politely sticks one of those 78 mph fastballs in Keyshawn’s ribs. Keyshawn drops the bat and goes to first without even looking at him.

Dave hits into a fielder’s choice. Gilbert’s throw is going to first before Keyshawn gets close. Just as well. I single into right. Dave stops at second. Up comes Mel with ducks on the pond.

Bresnahan trudges up the dirt path from the plate to the mound. Yeah, like the parks in Phoenix and Detroit and Philadelphia now, trying to look old-timey. I know what he’s telling Mathewson. Don’t let this guy beat you. Matty nods. Bresnahan swats him on the butt and gets behind the plate again.

Mathewson stretches, fires. Bresnahan’s mitt pops. “Strike one!” O’Day yells. Mel steps out. I don’t blame him. That isn’t well-placed junk. That’s gas, not quite as fast as Keyshawn but awful close. Christy’s got the big arm. With the dead ball and the big field, he just doesn’t use it all the time. He saves it for when he needs it.

Mel gets back in. More heat, this time two inches off the plate. Silk O’Day calls it a ball. Bresnahan jaws at him without turning around. Mathewson throws that fadeaway. Mel fouls it back onto the roof. It rolls down and they put it into play again. It’s scuffed? Dirty? They don’t care.

The next one makes Mel skip rope. Even count. Matty paints the outside corner, has to be 95. Mel’s frozen. The ump punches him out. He shakes his head as he goes back to the dugout. Pong-ju hits the first pitch hard, but Donlin runs it down in left-center.

Keyshawn gets a quick out in the bottom of the third. When Matty steps in, they look at each other for a second. They both know what’s coming. And it does. Keyshawn drills him in the butt, not too hard. Christy takes his base without a word. He gets away with hitting Keyshawn, and Keyshawn gets away with hitting him. Yeah, baseball.

Bresnahan’s sitting dead red when the count gets to 1-2. Keyshawn throws him a slow curve straight from one of the Dutch Spinners. Probably learned it from Kees. Roger almost comes out of his shoes swinging, but he’s a foot and a half out in front. He slams down the bat and cusses all the way to the dugout. George Browne, the right fielder, flies out on the first pitch.

Keyshawn’s due up again in the fifth. Eddie asks, “Got one more in ya?” Keyshawn nods. Eddie says, “Go get ’em, Tiger.” Keyshawn fans. They don’t pay him to hit.

Bottom of the fifth, the Giants put two on with one out. An error, a sharp single. Our pen heats up. The crowd laughs; they don’t play that way in 1905. Billy Gilbert, the Giants’ second baseman, grounds one up the middle. I dive. I get lucky — it sticks in the glove. I give Pong-ju a backhand flip from my belly, and he turns the DP. Inning over.

A split second after Pong-ju throws to first, Devlin, who’s running, knocks him sideways. In 2040, that ain’t kosher. It is here. The 1905 guys got warnings beforehand. So did we. Pong-ju just gets up and goes in.

Devlin picks himself up, too. “Hell of a play,” he says to me, and then, “Asshole.”

“Up yours, too,” I answer. He barks an almost-laugh.

Top of the sixth, Mel smacks one into the gap in right-center. Donlin can’t get it. Neither can Browne. It goes almost to the rope. Mel’s big, but he can motor. He zooms through a stop sign and beats the throw home. Insurance run.

Last four innings, we whipsaw the Giants: righty-lefty-right-lefty. They can’t get used to anybody. They put a couple of guys on, but don’t really threaten. McGraw lifts Mathewson in the eighth. Matty’s no automatic out, but Sammy Strang’s a real hitter. He works a ten-pitch walk, in fact; the game slows down while they throw back the foul balls. Doesn’t help, because Bresnahan pops up.

Joe McGinnity pitches the ninth. We get one more run on two singles and a sac fly. The second single’s mine, so I feel good.

Adilson closes out the bottom of the ninth in order. Fans start filing out unhappily. Coogan’s Bluff empties. “Final score, Los Angeles Angels from 2040, three; New York Giants, nothing. Winning pitcher, Fredericks. Losing pitcher, Mathewson,” the PA announcer bellows. He’s never heard of saves. Adilson gets one anyhow.

We clean up. We change. The Giants want nothing to do with us: McGraw’s a sore loser. We go back to the hotel. Can’t wait to pass through the portal again. The past is kinda interesting to visit, but you wouldn’t want to live there.

HARRY TURTLEDOVE has been a baseball fan since 1956, when dinosaurs like the PCL Los Angeles Angels and Hollywood Stars roamed the earth. He’s been a stats-crazed baseball fan since he started collecting baseball cards a couple of years later. A 50-plus year addiction to APBA baseball sure doesn’t help. This shows up in his writing in the current story, in earlier ones like “Batboy,” “Designated Hitter,” “The House That George Built,” and “The Star and the Rockets,” and in the Depression-era semipro-baseball fantasy novel, The House of Daniel.