Vic Willis: Turn-of-the-Century Great

This article was written by Stephen Cunerd

This article was published in 1989 Baseball Research Journal

He ranked with contemporary pitching stars like Iron Man McGinnity, Three Finger Brown, Jack Chesbro, and Rube Waddell. So why isn’t Vic Willis in the Hall?

TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY BASEBALL: It was a time of uniforms with baggy pants and no number. A time when players used gloves with no padding that they left in the field between innings. A time of ballparks with no lights. The parks were in the middle of the city because that’s where the fans were, and where the parks could be reached by public transportation such as trolleys. The games were all played on natural grass and without the help of electronic scoreboards and video replays.

It was, for all that, a time similar to today, because the nation was filled with baseball fans who loved the game and regularly followed their favorite teams and players. They watched their local team in person when it played at home, followed the newspaper reports of road games and pennant races, and collected baseball cards of the stars of the day.

Baseball at the turn of the century was a game dominated by the pitchers. The mound had been moved back to its present distance of 60 feet 6 inches. The great pitchers threw overhand, and many were experimenting with the curveball and other unusual deliveries. In the l880s, each team only had two or three pitchers. By 1900, most teams used three or four starters so that a pitcher could rest between starts, and carried several other pitchers as well. Team batting averages were low, and there were few really great hitters, In the American League, Nap Lajoie was the premier hitter, and would be joined later in the decade by Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker. Honus Wagner of the Pirates dominated the National League hitting scene, along with teammates Ginger Beaumont and Fred Clarke. It was a dead-ball era, home runs were scarce, runs were scored by grouping hits and stealing bases, and defense was becoming increasingly important.

Mostly, however, the turn of the century was a time for great pitchers. The 1890s featured Cy Young, Kid Nichols, and fireballing Amos Rusie. The l900s would bring Christy Mathewson, Eddie Plank, Joe McGinnity, Rube Waddell, Mordecai Brown, and Addie Joss, all Hall of Famers. One great turn-of-the-century pitcher, however, has thus far been bypassed in the Hall-of-Fame voting. Vic Willis is still waiting to join the honored greats at Cooperstown.

Willis, who was born in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1876 and pitched in Harrisburg and Syracuse before making it to the majors with Boston in 1898, is like so many of his contemporaries, mostly a name in the record books. There is virtually no one still living who saw him pitch and only a few who have talked to someone who has. Those who saw him, though, remember one of the National League’s truly great turn-of-the-century hurlers. They remember his pitching duels against Mordecai Brown of the Cubs and Joe McGinnity of the Giants. They remember a big righthander with a great curveball who is still waiting outside the door at Cooperstown.

Victor Gazaway Willis, 6’2″ and 185 pounds, worked for the Boston Beaneaters, Pittsburgh Pirates, and St. Louis Cardinals from 1898 to 1910. He spent his first eight seasons in Boston, then four in Pittsburgh before wrapping up an outstanding career with one year in St. Louis. Physically, he would remind modern fans of Robin Roberts or Tom Seaver, powerful righthanders who tend to dominate a game, especially after the first few innings. Willis was known for both a powerful curveball and a habit of completing everything he started. In his 13 major league seasons, Willis won 248 games, including 20 or more in eight different seasons. He hurled 50 career shutouts, pitched a no-hitter against Washington in 1899, and three one-hitters later in his career. In the 1902 season, Willis won 27 games and led the league in strikeouts, innings pitched, and complete games. His 45 complete games represent a modern NL record that still is standing 86 years after he accomplished the feat.

Willis joined the Boston team as a twenty-two-year-old rookie in 1898. The Beaneaters were a hard team to break into at this time, because they had just won the NL pennant in 1897 and had been a strong team throughout the 1890s. The team featured several future Hall of Famers, Jimmy Collins, Hugh Duffy, Billy Hamilton, and Kid Nichols. Willis replaced an aging Jack Stivetts in the Boston rotation and proceeded to win 24 games while losing only 13. Boston repeated as NL champs and, if they had been giving such awards, Willis would have handily won Rookie of the Year honors.

At this time in baseball’s history, a major change was taking place in the type of player making a career out of baseball and in the team image that was being presented to the fans. Frank Selee, who managed the Boston team, believed strongly that the game had developed an image that was much too rowdy. As a result, he deliberately recruited players who would fit a more gentlemanly image. He believed that this was not only the right approach, but also one that would increase fan interest in the game.

Vic Willis fit right in with Selee’s approach. He was described in the Boston newspapers of his time as a gentleman both on and off the field. His loyalty was such that, when many players jumped to the new American League for more money, he stayed with the Boston club. By 1906, he was the National League pitcher with the longest continuous service in the league.

In 1899, in only his second season, Willis established himself as the premier pitcher in baseball, winning 27 while losing only 8. His ERA (2.50) was second to Al Orth’s by only .01. He led the league in shutouts and in fewest hits allowed per nine innings. Boston won 95 games but finished second to a Brooklyn team featuring future Hall of Famers Willie Keeler and Joe Kelley. In that season, Willis pitched his no-hitter, besting Washington in August.

After winning 51 games in 1898 and `99, Willis struggled in 1900 through one of his few off-seasons, as his victory total dropped to 10, against 17 losses.

BOSTON AT THIS POINT was a team on the decline. By 1901, Collins and Duffy had jumped to the new American League and Hamilton was well past his prime. Accordingly, there was little support for the pitching staff. First baseman Fred Tenney, a defensive standout, was also one of the few consistent hitters remaining in the Boston lineup. Despite playing for a weak team, however, Willis continued to be a big winner during the first several years of the century. In 1901, he posted his third 20-win season, and led the league in several categories defining pitching excellence. He allowed the fewest baserunners per nine innings, and led the league in shutouts.

In 1902, Willis put up durability marks that are still standing. He worked 411 innings, joining Joe McGinnity as the only modern NL hurlers to exceed 400 innings in a season. It was during this year that Willis completed 45 of his 46 starts, winning 27 of them. He posted an ERA of 2.20, pitched four shutouts and led the league with 225 strikeouts. Imagine the salary this performance would draw in the 1980s market!

For the next three years, Boston was an extremely weak-hitting team and pitchers struggled to get every victory. The team never finished higher than sixth place, and could get no closer than 32 games out of first place. But in spite of limited support, Willis continued to be an effective pitcher. In 1903, he won 12 games. In 1904, although leading the NL in losses with 25, he had a fine ERA, posted 18 wins, finished second to Christy Mathewson in strikeouts, and tied for the league lead in complete games.

In 1905, he set the modern National League record for losses in a season with 29. As many baseball analysts have observed, it takes an outstanding pitcher to lose 20 games in a season because no manager is going to keep pitching him otherwise. During that season, Willis was second in the league in innings pitched and complete games, and four of his 11 victories were shutouts.

After the 1905 season, Willis was traded to Pittsburgh for third baseman Dave Brain, outfielder Del Howard, and pitcher Vive Lindaman. This was one of the early examples of a trading principle that has been true down through the years: trading quantity for quality. There have been numerous examples of teams that packaged several good players to a weak team to obtain the star who would make a difference for a pennant contender. This was true for the Pirates at this time. They had been chasing the Cubs and Giants for several years since their flags in the early 1900s. Willis was the key addition who kept them in pennant contention for the rest of the decade and brought them a world championship in 1909.

Willis pitched in Pittsburgh for four years, winning 20 or more games in every season and posting a total record of 90-47 as a Pirate. In addition, he pitched 23 shutouts. Only Hall of Famers Mordecai (Three Finger) Brown and Christy Mathewson were pitching at a comparable level. In 1906, Willis’s first year in Pittsburgh, he was 22-13 with a 1.73 ERA and did not allow a home run in the entire season. In 1907, he won 21 more, and in 1908, with the Pirates in the battle for the pennant right up to the last day of the season, Willis won 24 more. Then in 1909, Willis was a 23-game winner again, as the Pirates swept to the NL crown and won the World Series, beating Detroit.

THE 1909 PIRATES were a great team, featuring Hall of Famers Honus Wagner, who batted .339 to win his fourth consecutive batting title, and Fred Clarke, who played left field and managed the team to a 110-42 record. As the Pirate ace, Willis also had the honor of pitching the first game played in the new Pirate stadium, Forbes Field. Over 30,000 fans were on hand June 30 to see the Pirates play the Cubs. During this outstanding 1909 season, Willis also put together a personal 11-game winning streak.

After the 1909 season, Willis was sold to St. Louis, where he wrapped up his career a year later. Without Willis, the Pirates dropped to third in 1910 and didn’t win another pennant until 1925. During his 13-year career, Willis was a major factor in championships for both Boston and Pittsburgh and is remembered as one of the great pitchers for both franchises.

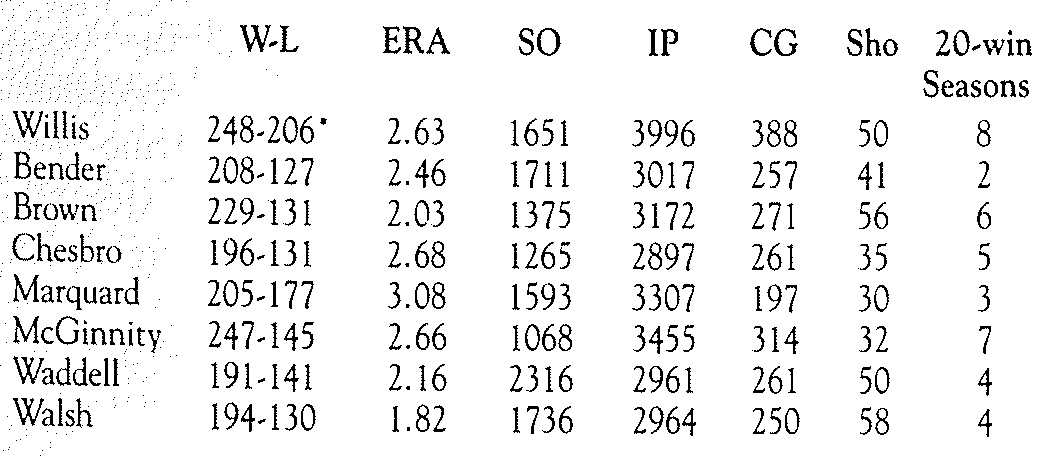

Willis was a contemporary of several Hall-of-Fame pitchers, and the table compares his career statistics to theirs. It is of particular significance to compare Willis to this group because they played in the same era, against some of the same competition, and under the same playing conditions. Slight variations in these statistics will exist, since scoring rules differed from those in effect today. However, the conclusion seems obvious. If these men are worthy Hall of Famers – and most baseball experts believe they are – then Vic Willis belongs in there with them. Willis posted more wins, more 20-win seasons, more innings pitched, and more complete games than all of them. Even though he played a significant portion of his career for weak teams, Willis posted a fine ERA and is among the all-time leaders in careers shutouts.

This is not an attempt to discredit any of the players already enshrined at Cooperstown, only an effort to indicate that Willis belongs with them. Willis has more career victories than twenty-two of the pitchers already elected. He has a better earned run average than twenty-eight of them and more shutouts than thirty-three of them.

In addition to the statistical case for Vic Willis’s election to the Hall of Fame, there is now a moral case as well. Willis is the only player in baseball history to receive 75 percent of the vote in a Hall of Fame election and not be enshrined at Cooperstown. In the 1986 Veterans Committee election, Bobby Doerr, Ernie Lombardi, and Willis all received 75 percent or more of the votes cast. Since the Veterans Committee has a rule limiting the number of electees in any year to two, only Doerr and Lombardi made it into the Hall that year.

In the 1987 election balloting, the committee had difficulty agreeing and elected only one person, Ray Dandridge. No one was elected by the committee in 1988, and in 1989 the honors went to Red Schoendienst and Al Barlick.

But the fact remains: The statistical evidence and the moral principle both argue for the election of Vic Willis.

STEPHEN CUNERD is wage-and-salary manager for a Philadelphia-area hospital.

*The authorities vary slightly on Willis’s exact won-lost record, The figures given in this article are believed to be correct.