Voices for the Voiceless: Ross Horning, Cy Block, and the Unwelcome Truth

This article was written by Warren Corbett

This article was published in Fall 2018 Baseball Research Journal

“The general public, or baseball fan, when he thinks of baseball thinks of the major leagues. He thinks of Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams. He thinks of huge salaries, of terrific baseball parks and beautiful lights and marvelous conditions, hotels, trains. That is baseball. Only 5 percent of baseball players in the United States play that way.” — Ross Horning1

Behind the sentimental rhetoric of the national pastime, Organized Baseball grew into a $100 million industry in the boom times after World War II. With 59 minor leagues operating at the peak, and around 10,000 players, the professional game touched 46 of the 48 states. No one yet knew that the game stood on the brink of wrenching change that would continue into the twenty-first century.

By 1951 the attendance trend was pointing downward. The devastation of the minors had begun when Congress cracked open a window on the business of baseball for the first time. The House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power collected financial data, contracts, working agreements, and other internal documents that had never before been made public. The hearings were part of a broad investigation of economic concentration in industries including steel, newsprint, aluminum, and defense.

The subcommittee was considering three bills that would give congressional approval to baseball’s exemption from antitrust laws and extend the exemption to other professional sports leagues. Chairman Emanuel Celler, a Democrat from Brooklyn, said his purpose was to “strengthen and fortify” baseball’s legal position, which was under attack in court.2 But as he listened to testimony, Celler sounded increasingly skeptical of the antitrust exemption and its companions: the renewal clause that denied players freedom to choose their employer and the territorial-rights rules that denied clubs freedom to move to a different city.

The first witness at the opening hearing on July 30 was Ty Cobb, a name guaranteed to attract press coverage. Cobb had little to offer, but he did endorse the reserve clause while saying veteran players should be permitted to take salary disputes to arbitration.

With the commissioner’s office vacant — Happy Chandler had recently been dumped by unhappy owners — Organized Baseball’s leadoff witness was National League President Ford Frick, who would be elected commissioner less than two months later.

“Frankly, gentlemen, I don’t see why all the furor about the reserve clause,” Frick declared. “Basically, it is a long-term contract which is nothing unusual where distinctive personal services are contracted for. I read by the papers that [comedian] Milton Berle has just signed such a contract for 30 years.”3 The subcommittee report noted that Berle had been free to negotiate with any television network before he signed with NBC — a choice not available to ballplayers.

Two unknown young men stepped forward to challenge Frick’s benign view of owner-player relations. They were voices for the voiceless, the 95 percent in the minor leagues.

The Grad Student

Ross Horning, called “Bumps” in his playing days, had his first collision with the reserve clause when he was a 21-year-old shortstop with Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in 1942, warming up for a road game in Duluth, Minnesota.4 “I was playing catch with one of the players, and a fellow (from the Duluth team) came along the fence and said, ‘What size uniform do you want?’ I said, ‘What do you mean? I’ve already got one.’ And he said, ‘Well, you’ve just been sold to us.’”5

Ross Horning, called “Bumps” in his playing days, had his first collision with the reserve clause when he was a 21-year-old shortstop with Sioux Falls, South Dakota, in 1942, warming up for a road game in Duluth, Minnesota.4 “I was playing catch with one of the players, and a fellow (from the Duluth team) came along the fence and said, ‘What size uniform do you want?’ I said, ‘What do you mean? I’ve already got one.’ And he said, ‘Well, you’ve just been sold to us.’”5

The Sioux Falls club had just left home for a two-week road trip, meaning the team would be paying Horning’s living expenses. But Duluth was beginning a two-week homestand, and he would have to rent a room. That extra expense would put a considerable dent in his $75-a-month paycheck. He told the Duluth owner he wanted to stay with Sioux Falls. “We argued until about 2 o’clock in the morning, and I knew before we finished that he would tell me the obvious fact, that I could not play for any other team in the United States anyway, and so I may just as well play for him.”6

When Horning read about the upcoming hearings, he wrote a five-page letter to Chairman Celler urging him to investigate the reserve clause’s role in oppressing minor leaguers. “If your committee only calls outstanding players, managers, and owners, it will not reach the core of the reserve clause controversy,” he said.7

He had quit Organized Baseball after five seasons in Class C and D and service as an army pilot in World War II. His .228 batting average in his first full professional season had convinced him that he would never join the 5 percent. He kept playing ball to earn money for college.

As a graduate student at The George Washington University in the nation’s capital in the summer of 1951, Horning was preparing to take the State Department’s Foreign Service entrance exam. The subcommittee’s associate counsel, future Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, interviewed him, and he was invited to testify on August 7. He had plenty to say.

Horning gave the congressmen a vivid and depressing picture of life in the low minors. The Sioux Falls Canaries traveled on a decrepit Ford bus known as “Stucker’s Steamer” after the team owner, Rex Stucker. “We used to pile all our suitcases, baseball bats, and other things in this bus and leave Sioux City [Iowa, after a road game] about midnight and travel to Cheyenne, Wyo. It was about 600 miles away. And we were to get there about 4:30 the following afternoon and play a game in Cheyenne, Wyo., that night. … That is the common practice to save hotel bills.”8

He recalled his second encounter with the reserve clause, when he was back with Sioux Falls after the war and attending Augustana College there in the offseasons. The parent Chicago Cubs ordered him to move to another Class C farm club in Hutchinson, Kansas. He refused to go, and the Cubs suspended him. After two weeks with no income, he agreed to report, but it cost him. He had to rent a hotel room in Hutchinson while continuing to pay for his room at the Sioux Falls YMCA “so that when I came back in the fall I would have a place to live, to go to college.”

Horning said the reserve clause was part of baseball’s “mercantile theory of economics, whereby each major league club has little colonies all over the United States, and the primary purpose of these colonies or minor league clubs is to produce players for the parent club.”9 (He certainly didn’t talk like a ballplayer.) “It is difficult to see how 16 owners should have complete control of America’s national game.”10

He attacked the owners’ central argument that the reserve clause was needed to ensure fair competition between rich and poor teams. On the contrary, he said, benchwarmers on rich clubs could help weaker teams if they were free to choose where to play. “If there were no reserve clause, then [a team] could say to a man on the bench of the wealthy team, ‘You can play regular with us.’ … He would rather play, surely.”11

Horning pointed out that a minor leaguer could be released with no notice and no severance pay, not even bus fare home. “Imagine that Ted Williams was hitting .200 on the first of July. He would never lose his job. He would never be fired. He would always receive his year’s contract.

“That is not true in the minor league case. If a man was hitting .200, he would probably lose his job on July 2.”12

Horning continued: “The contract is binding on only one party. There is no binding factor as far as the club is concerned. … If you live to be 75, you cannot play for any other baseball team than the owner says — unless you get an absolute release, that is. You have no choice.”13

Under questioning, Horning acknowledged that he had no specific ideas on how to replace the reserve clause. “Not every ballplayer is a major league ballplayer or ever will be a major league ballplayer,” he concluded. “But I feel they have a right to play where they want to and work where they want to, and to feel that a contract is binding upon the other party as well as upon themselves. That is my entire interest in being here.”14

The Salesman

Seymour “Cy” Block was never shy about speaking up for himself. When he thought he had been wronged, which was often, he went straight to the top. At different times he confronted Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, National League President Ford Frick, and Dodgers President Larry MacPhail over his disputes with baseball management. All his appeals failed.15

Seymour “Cy” Block was never shy about speaking up for himself. When he thought he had been wronged, which was often, he went straight to the top. At different times he confronted Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, National League President Ford Frick, and Dodgers President Larry MacPhail over his disputes with baseball management. All his appeals failed.15

As a 21-year-old in 1940, the Brooklyn boy told a sportswriter, “There’s no room for sissies in the minors today.” He had his own horror stories of overnight bus rides: “We sit up all night, sing songs I can’t repeat, drink a million cokes and when we get out our fannies are as flat as a phonograph record.”

“You can’t stand the food and the bus rides unless you are young and strong and always have before you the picture of yourself in a big league uniform,” he added. “I’ll make the Big Top some day. You wait and see.”16

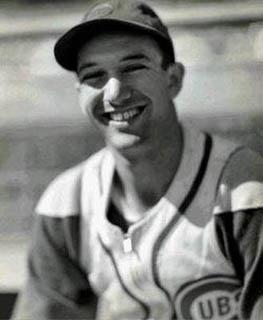

He made it, but only for a short pot of coffee with the Chicago Cubs. He totaled 17 games in three trials before and after wartime Coast Guard service, and had a Moonlight Graham moment in the 1945 World Series as a pinch-runner who never took the field or came to bat. In 10 years in the minors, the “peppery second baseman”, as The Sporting News called him, won a Most Valuable Player award and batted over .300 six times17. He had been released by Triple-A Buffalo in April 1951 and was now selling insurance.

Block had written to Celler, his hometown congressman, volunteering to testify.18 Appearing on October 15, he asserted that he was speaking for most minor leaguers, who didn’t dare complain “because they would be blacklisted.”19

“Actually, the reserve clause is just the final breaking point of a number of grievances that have been building up for years among ballplayers,” he said as he reeled off a litany of injustices inflicted on players in the minors.20

- “In your major league contract, you have a minimum salary of $5,000 and no maximum. You can go as high as the sky, which is fine. On the other hand, in your minor league contract you have no minimum. There is no minimum in any league, but you have a maximum. Outside of a very few ballplayers, the maximum salary you can attain in the minor leagues is about $6,000.”

- “In your major leagues, if you get a release, if they release you, you are entitled to 1 month’s pay. … In the minor leagues, you could be playing in Podunk and get released in 24 hours, without pay, and you are stuck.”

- “In the major leagues, if you are injured you are paid for the season. In the minor leagues they are only liable for two weeks’ salary.”21

- “In the major league contract, when the season ends, they pay your way home. In the minor league, you can live in New York and play in California, and when it ends, you have to pay your own way home.”22

- A minor leaguer’s pay was cut when he was demoted to a lower level. “That is not fair, because when you sign a contract you figure that is the salary you’re going to get.”23 Unlike the majors, minor leaguers received no moving expenses, no expense money during spring training, and no pension plan.

Block’s personal grievance concerned the waiver process, “the farce in baseball.”24 He believed he had been cheated out of a fair shot in the majors because the Cubs had put him on waivers, then refused to sell him when the Phillies and Pirates expressed interest. He thought the Cubs had invoked a “gentlemen’s agreement” to send him down to Double A in violation of the rules.

After unloading that barrage, Block insisted that his objection to the reserve clause was limited to its impact on minor leaguers. Major league players, he said, “are really well taken care of.”25

Ross Horning testifies during the Celler hearings on baseball’s antitrust exemption on August 7, 1951, in Washington, DC. (Associated Press photo)

Signifying Nothing

The tame sporting press largely ignored or ridiculed the minor leaguers. Block appeared on the same day as Clark Griffith, ancient owner of the Washington Nationals, who dominated news coverage. Horning may have wished he had passed unnoticed as well.

“Ross Horning’s record indicates he can’t hit a lick and has no chance to move up in baseball,” sneered Francis Stann of the Washington Evening Star. Never mind that Horning had no desire to move up in baseball. Seattle Times columnist Eugene Russell dismissed him as a “bush leaguer” who was biting the hand that had paid him enough to fund his college education.26

In the days following Block’s testimony, several active major-league stars parroted the owners’ line, exhibiting a kind of Stockholm Syndrome. Detroit pitcher Fred Hutchinson — the American League player representative, no less — pronounced the reserve clause necessary and reasonable. So did Red Sox shortstop Lou Boudreau. “Without the reserve clause, I don’t think that baseball could operate,” said Dodgers shortstop and captain Pee Wee Reese.27

After 16 days of hearings, 33 witnesses, and 1,643 pages of transcript, the subcommittee decided to do nothing. Its final report recommended that Congress take no action on baseball’s antitrust exemption because the issue was before the courts.28 Eight lawsuits challenging the exemption were pending.

In 1953 the US Supreme Court rejected an appeal by former Yankees farmhand George Toolson. “We think that, if there are evils in this field [baseball] which now warrant application to it of the antitrust laws, it should be by legislation,” the court majority said.29 Ballplayers were trapped in a Catch-22: Congress left it up to the courts, and the Supreme Court left it up to Congress.

Different Ballgames

Ross Horning and Cy Block were born 17 months and 1,400 miles apart, Block in Brooklyn in 1919 and Horning in Watertown, South Dakota, in 1920. They died six months apart in 2004 and 2005. They never met, as far as is known. The two men followed different paths after baseball and achieved more success than they ever had on the diamond.

Block exuded salesmanship. Less than a decade after he began selling life insurance, he was his company’s top performer in the country. He rented a 40-foot-tall billboard overlooking Times Square in New York, with his photo in his Cubs uniform and the slogan, “Cy Block Says life insurance is the home run investment. With it you can’t strike out.”30

Eventually he went out on his own to sell insurance and pension plans, and his CB Planning firm topped $100 million in annual sales. Cy and Harriet Block were generous supporters of Jewish charities in the United States and Israel. “Maybe God looked down and said, ‘Block, you know, you should have been a helluva ballplayer,’” he said, “and he waved his hand, and whatever I was supposed to do in baseball happened to me in insurance.”31

Ross Horning completed his Ph.D. at George Washington while playing in independent leagues during several summers. He found that he could make more money in semipro ball than in Class C. He could choose where he played and enjoy a pleasant vacation with his wife, Maxine. After studying in India as aFulbright Scholar, he became a professor of history at Creighton University in Omaha.

Dr. Horning taught the history of Russia, India, Ireland, Scotland, and Canada, spicing his lectures with corny humor and occasional juggling of tennis balls. He served three terms as faculty president, headed the university’s athletic committee, and put in time on practically every other committee on campus. He fed his competitive fire by playing intramural softball and pickup basketball with students into his 70s, even after a hip replacement. Upon his death at 84, Creighton established a scholarship and an annual history lecture in his name.

Horning revisited the plight of minor leaguers in 2000 for an essay in SABR’s The National Pastime. While major leaguers had won free agency and fabulous salaries, he wrote that the minor-league contract had actually become more oppressive. True, it granted a player free agency after six years — for the few who lasted that long — but he could still be sold or released without notice. In addition, the new contract gave the team year-round call on his services, so he could be prohibited from getting an offseason job to supplement his poverty-level income or, like Horning, going to school.

That was the nature of professional baseball, Horning wrote: “a wonderful, enjoyable sport that is also very cruel.”32

Epilogue

Minor leaguers were still second-class citizens in 2018. A group of players had filed suit seeking to be paid the federal minimum wage, $7.25 per hour, with overtime for working more than 40 hours a week. This time Congress had no hesitation about interfering with the courts. In March 2018 Congress passed and President Trump signed legislation that exempted baseball players from federal overtime laws. The provision, pushed by lobbyists for major- and minor-league baseball, was inserted in a 2,232-page government funding bill, even though Congress had never held hearings or debated the issue.33

Garrett Broshuis, a former minor-league pitcher who is the lead attorney for the players, was trying to keep the lawsuit alive by seeking overtime pay under the various state minimum wage laws. The suit was pending as this issue of Baseball Research Journal went to press.

WARREN CORBETT is the author of “The Wizard of Waxahachie: Paul Richards and the End of Baseball as We Knew It” and a contributor to SABR’s BioProject. He is a 2018 winner of the McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

Acknowledgments

Cindy Workman of Creighton University contributed information about Ross Horning. The research staff of the Library of Congress led me to the transcript of the Celler hearings. Judith Adkins of the National Archives Center for Legislative Archives provided the monopoly subcommittee’s files. Attorney Garrett Broshuis briefed me on his lawsuit on behalf of minor leaguers.

Notes

1 Study of Monopoly Power, Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 82nd Congress, First Session, Serial No. 1, Part 6: Organized Baseball. 372 (1952). Hereafter cited as “Hearings.”

2 “Truman Approves Baseball Reserve Clause Investigation,” Washington Post, July 19, 1951.

3 Hearings, 30.

4 A note on terminology. While the “reserve clause” itself had been replaced by that point, several provisions in the contract added up to the same effect and were referred to collectively as “the reserve clause.” The Celler hearings used that terminology throughout. All baseball witnesses used the term ‘reserve clause’ to describe the contract provisions that bound a player to his team, including the team’s right to trade or sell the contract.

5 “Ross Horning: Scholar, wit, and athlete,” Creighton University Colleague, July 1985: 8; “Younger Shackles Duluth Team, 8-0,” Sioux Falls Argus-Leader (South Dakota), July 9, 1942. Horning was sold because the Sioux Falls owner needed fast cash to pay expenses for the road trip.

6 Hearings, 352.

7 Ross C. Horning to Representative Cellar [sic], May 14, 1951, “Correspondence A-H,” Papers of the House Subcommittee on the Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary from the 82nd Congress, National Archives Center for Legislative Archives. Hereafter cited as “subcommittee papers.”

8 Hearings, 348-9.

9 Hearings, 359.

10 Hearings, 374.

11 Hearings, 374.

12 Hearings, 372.

13 Hearings, 393-4.

14 Hearings, 396.

15 Cy Block, as told to Leonard Lewin, So You Want to Be a Major Leaguer? (Privately published, 1964). Block’s memoir of his baseball career was a promotional pamphlet for his insurance business.

16 Jimmy Powers, “Minor Leaguer’s Grief and Hopes,” New York Daily News, reprinted in The Sporting News, November 14, 1940.

17 “Texas League,”The Sporting News, June 25, 1942.

18 Cy Block to Hon. Emanuel Celler, July 23, 1951, in subcommittee papers.

19 Hearings, 587.

20 Hearings, 582.

21 Hearings, 583.

22 Hearings, 589.

23 Hearings, 586.

24 Hearings, 589.

25 Hearings, 590.

26 Francis Stann, “Win, Lose, or Draw,” Washington Evening Star, August 8, 1951; Eugene H. Russell, “Bush Leaguer Talks,” Seattle Times, August 8, 1951.

27 Hearings, 852. Subcommittee records indicate that the three major leaguers did not volunteer to testify. They were summoned by Chairman Celler, probably at the suggestion of baseball’s lobbyist, Washington attorney Paul Porter, because they were considered friendly to the owners’ position.

28 Organized Baseball, Report of the House Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary, 82nd Congress. 232 (1952).

29 Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc., 346 U.S. 356 (1953), 346.

30 Block, So You Want to Be a Major Leaguer? Photo inside back cover.

31 Peter Ephross and Martin Abramowitz, Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012), 68.

32 Ross Horning, “Minor League Player,” The National Pastime 20 (SABR, 2000), 104.

33 Bill Shaikin, “Minor Leaguers Could Be Paid Minimum Wage — and No More,” Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2018.