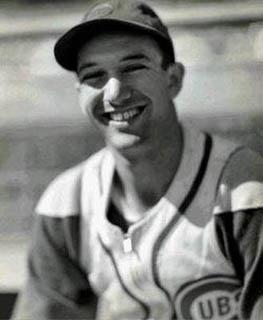

Cy Block

Cy Block was never shy about speaking up for himself. When he thought he had been wronged, which was often, he went straight to the top. At different times he confronted Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, National League President Ford Frick, and Dodgers President Larry MacPhail over his disputes with baseball management. His voice carried as far as the US Congress, where he testified to protest baseball’s treatment of minor leaguers. All his appeals failed.

Cy Block was never shy about speaking up for himself. When he thought he had been wronged, which was often, he went straight to the top. At different times he confronted Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, National League President Ford Frick, and Dodgers President Larry MacPhail over his disputes with baseball management. His voice carried as far as the US Congress, where he testified to protest baseball’s treatment of minor leaguers. All his appeals failed.

Block had three brief trials with the Chicago Cubs as a second and third baseman during and after World War II, but believed he was cheated out of his chance to stick in the majors. After enduring disappointment in the game he loved, he talked his way to a multimillion-dollar fortune. “Maybe God looked down and said, ‘Block, you know, you should have been a helluva ballplayer,’ and he waved his hand, and whatever I was supposed to do in baseball happened to me in insurance.”1

Seymour Block was a Brooklyn boy, born on May 4, 1919, to Russian immigrants Abraham and Jenny (Levitsky) Block. The family lived near Ebbets Field, and Seymour began sneaking into the ballpark when he was 9 by climbing a 12-foot fence behind the bleachers. The first game he saw changed his life: “Dazzy Vance was pitching, Babe Herman was hitting, and that was it. I never thought of anything else after that.”2

He played ball from daybreak until dark, or until his mother came after him. “Baseball is for bums,” she told him. “Study to be a lawyer or a doctor.”3 That didn’t discourage him. Neither did the high school coach who told him he was too small to make the team at 5-feet-5 and about 110 pounds. He formed his own team, the Falcons, and organized a neighborhood sandlot league.

When he was 17, Block attended tryout camps with the Dodgers and Pirates, but they weren’t interested. He saved money from part-time jobs to go to the Joe Stripp Baseball School in Orlando, Florida, where he paid $50 for five weeks of instruction plus $7 a week for room and board. Stripp, a former major leaguer, told him, “‘Cy, you’ll never make a ball player.’ He wouldn’t take it and demanded, ‘Why not?’ I told him he wasn’t big enough.” Stripp advised him to drink more milk, eat ice cream, and sleep 10 to 12 hours every night. The next year Block was back. “In that year he had gained nearly five inches and 45 pounds!” Stripp concluded, “Sometimes we guess wrong, and this boy Block sure made me eat my words.”4

One of the school’s instructors, the future Hall of Fame shortstop Joe Tinker, recommended him to the Memphis club of the Class A-1 Southern Association. Now grown to 6 feet and around 180 at age 19, he was farmed out to play third base for Class-D Paragould, Arkansas, in 1938. He set a Northeast Arkansas League record with 34 stolen bases while batting .323. The only Jew in the league, he faced taunts and knockdown pitches.

He was promoted to Class-C ball in Greenville, Mississippi, where he had his first run-in with baseball authorities. Block said Memphis had promised him $125 a month, but Greenville paid him only $85. After the head of the minor leagues, William Bramham, rejected his appeal, he wrote to Commissioner Landis asking to be declared a free agent because of a breach of contract. Landis didn’t reply until a year and a half later, when he met with Block and agreed to investigate his claim.5

Block climbed the minor-league ladder one rung at a time, batting over .300 in each of his first four stops. At Class-B Macon, Georgia, in 1940, his roommate was the combative shortstop, Eddie Stanky, who was already studying to be “the Brat.” “Eddie would go up to bat and throw dirt on the plate, the ump would go and clean it off,” Block remembered. “He’d throw dirt on the plate again and the ump would clean it off again. He’d take a swing back with his bat and hit the catcher in the mask, who by this time was so riled up he’d give the sign for a knockdown pitch that would make your hat stand up. Stanky’d take the pitch for ball one and proceed to laugh at the pitcher and scream how he couldn’t throw a fastball.”6

Back home in Brooklyn, some of Block’s friends had formed a fan club and combed the newsstands for Georgia papers to follow his exploits. That drew the notice of Jimmy Powers, a top columnist for the New York Daily News. “There’s no room for sissies in the minors today,” Block told him. “You can’t afford to get sick or lonesome. We often finished a game in Spartanburg, S.C., at midnight, piled into a bus at 1 a.m. and rolled into Jacksonville, Fla., next day at 10 a.m. with a Sunday doubleheader scheduled at 1 p.m. … We sit up all night, sing songs I can’t repeat, drink a million cokes and when we get out our fannies are as flat as a phonograph record.

“You can’t stand the food and the bus rides unless you are young and strong and always have before you the picture of yourself in a big league uniform,” he added. “I’ll make the Big Top some day. You wait and see.”7

Following the 1940 season he went to Dodgers President MacPhail demanding a promotion, but returned to Macon after a brief holdout. In his second look at Class-B pitching, Block hit .357 with 112 RBIs and was voted the Sally League’s Most Valuable Player.

Judge Landis summoned him again during the World Series. The commissioner said he would have a strong case against Memphis if only he had something in writing to prove it. Block gave up, but he didn’t forget.8

MacPhail sold his outspoken farmhand to the Cubs, who moved him up to the Texas League, Class 1-A, in 1942. Playing second base for Tulsa, he was beaned early in the season. A primitive helmet padded with sponges saved him from serious harm, but his average fell to .276.

Called up in September, Block made his major-league debut at Cincinnati. Johnny Vander Meer struck him out on three high fastballs in his first at-bat. His next time up, teammate Jimmie Foxx tipped him that a curve was coming, and he singled to drive in a run. He followed that with a double to end the day 2-for-4. Starting eight more games, he finished with a gaudy .364/.417/.455 batting line. Manager Jimmie Wilson told him that Cubs third baseman Stan Hack planned to retire, and he would be the frontrunner for the job in the spring.9

History had other plans. Block learned that he would soon be drafted into the Army, so he enlisted in the Coast Guard in November. He spent most of the war at Ellis Island in New York harbor, guarding POWs and enemy aliens while playing ball for the base’s team.

In April 1943 Cy married his hometown girlfriend, Harriet Spector. He thought she was quite a catch; he entered her photo in New York’s Miss Subway contest. According to her husband, Harriet won but was disqualified because she was married.10

The Coast Guard set Block free on September 13, 1945. He rejoined the Cubs, who were on their way to the National League pennant. The club paid him $500 for playing in two games. Returning servicemen were eligible for the World Series, so Block had visions of “some good money after a few years of taking petty cash from Uncle Sam.”11

He sat until the ninth inning of Game Six, when he pinch-ran for Heinz Becker at first base. The next batter made the third out to end Block’s Moonlight Graham moment. He never took the field or came to bat.

His Cubs teammates voted to award Block and two other September returnees, Hi Bithorn and Clyde McCullough, Series shares of only $250 — $190 after taxes — one-fourth of the batboys’ shares. Block had brought Harriet to Chicago for the Series and bought tickets for some Coast Guard buddies. When he added up his expenses, he was $40 in the hole.

He was happy to be back in the game, except for one thing: Stan Hack, unretired, was still holding down third base. The Cubs signed Block to a $4,000 contract for 1946, then sent him to Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League. Like many ex-servicemen, he found that his legs couldn’t stand up to everyday play. He accepted a demotion to Double-A Nashville in June.

At 27, Block was going backward. He overmatched the Southern Association with a .354 average and was called up to Chicago in September. Playing six games, he went 3-for-13 (.231). On September 23 he pinch-hit in the ninth against St. Louis with the tying run on second. He hammered a drive to deep left-center, but Harry Walker climbed the Wrigley Field wall to haul it down. It was Block’s last big-league appearance.

The Cubs had used all of his minor-league options, so they sold him to Nashville before the 1947 season. General manager Jim Gallagher told him the club would bring him back to the majors if he had a good year. “I said, ‘Jim, I cannot do any better than the .350 that I hit for Nashville. I know there are two or three clubs in the big leagues that can use me. Give me a break.’”12 Gallagher was unmoved, but Nashville owner Larry Gilbert agreed to let Block try to make a deal for himself.

He said the Phillies and Pirates expressed interest, but both general managers told him that the Cubs had refused to sell him. Block had to pass through waivers before he could be sent down. He was convinced that the Cubs had invoked a “gentlemen’s agreement” to get other clubs to go along in violation of the rules.

Block appealed to National League President Ford Frick, who said he could do nothing. Block sat at home with his pregnant wife until his money ran out, then slunk back to Nashville. He took out his frustration on Southern Association pitchers, blasting away at a .360 clip with 50 doubles in 120 games.

That won him a promotion in 1948, but only as far as Triple-A Buffalo. At least he was closer to Harriet and their new daughter, Betty. He played three years for the Bisons, helping them win the International League pennant in 1949, but his enthusiasm had dimmed and his shrinking batting average showed it. By 1950 Buffalo, a Philadelphia Athletics farm club, was playing younger prospects, putting the 31-year-old Block on the bench. He was released on April 8, 1951, his eighth wedding anniversary. Sitting in a hotel room contemplating his future, he said, “It was then that I recalled my mother’s words: ‘Don’t be a baseball bum.’”13 He retired.

But he had a score to settle. His hometown Brooklyn congressman, Emanuel Celler, had announced that he would hold hearings on Organized Baseball’s antitrust exemption. The exemption and the reserve clause that bound players to their teams for life were under attack in court. Celler cast himself as the defender of the National Pastime: “Baseball is one of the finest things in American life, but it is in danger.”14 He declared that his purpose was to “strengthen and fortify” the game’s legal position.15

That touched Block’s hot button. He wrote to the congressman volunteering to testify about the mistreatment of minor leaguers. Since he was no longer active, he said he could speak for players who were afraid to speak for themselves.16

Opening its hearings on July 30, 1951, Celler’s Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power heard from a parade of baseball officials who defended the reserve clause as essential to ensure that rich teams couldn’t sign all the best players.

One former minor leaguer, Ross Horning, dissented. “Not every ballplayer is a major league ballplayer or ever will be a major league ballplayer,” he testified. “But I feel they have a right to play where they want to and work where they want to.”17

Block’s turn came on October 15. “Actually, the reserve clause is just the final breaking point of a number of grievances that have been building up for years among ballplayers,” he told the congressmen as he reeled off a litany of injustices inflicted on players in the minors.18

- “In your major league contract, you have a minimum salary of $5,000 and no maximum. You can go as high as the sky, which is fine. On the other hand, in your minor league contract you have no minimum. There is no minimum in any league, but you have a maximum. Outside of a very few ballplayers, the maximum salary you can attain in the minor leagues is about $6,000.”

- “In your major leagues, if you get a release, if they release you, you are entitled to 1 month’s pay. … In the minor leagues, you could be playing in Podunk and get released in 24 hours, without pay, and you are stuck.”

- “In the major leagues, if you are injured you are paid for the season. In the minor leagues they are only liable for two weeks’ salary.”19

- “In the major league contract, when the season ends, they pay your way home. In the minor league, you can live in New York and play in California, and when it ends, you have to pay your own way home.”20

- A minor leaguer’s pay was cut when he was demoted to a lower level, as his had been when Memphis sent him to Greenville. “That is not fair, because when you sign a contract you figure that is the salary you’re going to get.”21 Unlike the majors, minor league players received no moving expenses, no expense money during spring training, and no pension. Block had devised a pension plan for minor leaguers and presented his proposal to owners, but was rebuffed.

Block limited his criticism to the oppression of minor leaguers. Major-league players, he said, “are really well taken care of.”22 He did not argue for elimination of the reserve clause, but said it should be modified so that both major- and minor-league players had the right to arbitration of salary disputes.

After Horning and Block’s passionate pleas, major-league baseball rolled out three high-profile players to testify in support of the reserve clause. Pitcher Fred Hutchinson, the American League player representative, and shortstops Lou Boudreau and Pee Wee Reese parroted the owners’ line. “Without the reserve clause, I don’t think that baseball could operate,” Reese said.23

The subcommittee hearings fill 1,643 pages of transcript. When they were over, the congressmen decided to do nothing. They said Congress should pass no legislation on baseball’s antitrust exemption because the issue was before the courts. In 1953 the US Supreme Court ruled that it was up to Congress to decide whether to end the exemption. The buck-passing continues to this day, with a modified exemption still in place.

After baseball Block found stardom in the insurance business. He had started selling life insurance in the off-seasons because Harriet was pressing him to quit the game. “Quite frankly, just to get her off my back, I answered an ad in the newspaper,” he said years later. “Turned out to be the best break I ever had.”24

With his forceful personality and relentless work, he exuded salesmanship. He said he once made 57 cold calls in a single day, selling only two policies that netted him $22 in commissions. He took courses in estates and taxes at New York University to expand his knowledge. In his second year of full-time selling, he wrote $1 million in policies. Ten years later he was up to $6 million.

He opened an office on 42nd Street in Manhattan’s Broadway theater district and bought a 40-foot-tall billboard overlooking Times Square, with his photo in his Cubs uniform and the slogan “Cy Block says life insurance is the home run investment. With it you can’t strike out.”

He made sales calls four evenings a week, reserving the other nights for Harriet and their three daughters at home on Long Island. “My client is the pitcher and I am the batter,” he said. “Every negative reply is a curve ball which I try to hit out of the park.”25 Block formed his own company, CB Planning, to specialize in pension plans. He claimed $100 million in annual sales. He drove a Rolls-Royce with the license plate “LBA 325” — his lifetime batting average in the majors and minors.26

Block put his money to use in philanthropy. His firm sponsored youth baseball teams in New York. He served as president of the Sports Lodge of B’nai B’rith and sat on the board of directors of the Israel Tennis Center and the American Committee of the Maccabiah Games, often called the Jewish Olympics.

In the 1980s he returned to advocacy for ballplayers. The Major League Baseball Players Association had established a two-tier pension plan: Players who retired before 1970 got smaller payouts than those who came later. Earl Wilson, a 10-year man who retired in 1970, would receive up to $90,000 a year at age 62. Ted Williams, a 22-year man who retired in 1960, qualified for $30,348 when he reached 65. Block proposed a reorganization of the pension fund, and Hall of Fame pitcher Early Wynn led old players in lobbying for it, but they got nowhere.27

When Block was invited to play in a Cubs old-timers game in 1982, his former manager Charlie Grimm told him he was starting at third base. Grimm explained, “Stan Hack is dead now.”28

Cy Block died at 85 on September 22, 2004. Late in his life someone asked him how it felt to be a millionaire. “I knew how it would feel as early as September 8, 1942,” he said. “My first day in the major leagues.”29

Acknowledgments

Photo credit: cyblockbaseball.com. The research staff of the Library of Congress led me to the transcript of the Celler hearings. Judith Adkins of the National Archives Center for Legislative Archives provided the monopoly subcommittee’s files. This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and checked for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Sources

Portions of this story appeared in Warren Corbett, “Voices for the Voiceless: Ross Horning, Cy Block, and the Unwelcome Truth,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 47, No. 2 (SABR, 2018).

Notes

1 Peter Ephross and Martin Abramowitz, Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words, 68.

2 Victoria W. Guadagno, “Cy Block, His Second Successful Career,” Baseball Research Journal 11 (SABR, 1982). http://research.sabr.org/journals/cy-block-his-second-successful-career.

3 Cy Block as told to Leonard Lewin, So You Want to Be a Major Leaguer? (privately published, 1964), 7.

4 Frederick G. Lieb, “It’s Strictly Business with Stripp and His Students,” The Sporting News, February 12, 1942: 7.

5 Block, 25.

6 Guadagno.

7 Jimmy Powers, “Powerhouse,” New York Daily News, November 5, 1940: 46.

8 Block, 29.

9 Ibid., 34-35.

10 Peter S. Horvitz and Joachim Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball (New York: S.P.I. Books, 2001), 248.

11 Block, 36.

12 Study of Monopoly Power, Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, 82nd Congress, First Session, Serial No. 1, Part 6: “Organized Baseball” (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1952), 592. Hereafter cited as “Hearings.”

13 Block, 52.

14 Ted Smits, “Celler Says Baseball Violates Trust Law, Favors Exemption,” Washington Post, May 5, 1951: 13.

15 “Truman Approves Baseball Reserve Clause Investigation,” Washington Post, July 19, 1951: 13.

16 Cy Block to Hon. Emanuel Celler, July 23, 1951, in “Correspondence A-H,” Papers of the House Subcommittee on the Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary from the 82nd Congress, at the National Archives Center for Legislative Archives in Washington.

17 Hearings, 396.

18 Hearings, 582.

19 Hearings, 583.

20 Hearings, 589.

21 Hearings, 586.

22 Hearings, 590.

23 Hearings, 852. Subcommittee records indicate that the three major leaguers did not volunteer to testify. They were summoned by Chairman Celler, probably at the suggestion of baseball’s lobbyist, Washington attorney Paul Porter, because they were considered friendly to the owners’ position.

24 Guadagno.

25 Block, “Selling Life Insurance Is Like Playing Baseball,” Life Insurance Selling, June 1953, in his file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

26 Block’s lifetime batting average in baseball-reference.com, on the basis of incomplete statistics, calculates to .303. The Baseball Register reports .314.

27 Dave Nightingale, “Fattest Feline in Sports,” The Sporting News, May 12, 1986: 14.

28 Ibid., 16.

29 Guadagno.

Full Name

Seymour Block

Born

May 4, 1919 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

September 22, 2004 at Manhasset, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.