Walter O’Malley Was Right

This article was written by Paul Hirsch

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

An explanation of why Walter O’Malley was right in his decision to move the Dodgers to the West Coast.

An explanation of why Walter O’Malley was right in his decision to move the Dodgers to the West Coast.Few men in sports history have been vilified to the extent Walter O’Malley was when he moved the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles in 1957. Over recent decades, New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses has begun to share some, if not all, of the blame for the Dodgers’ move. Countless trees have died supporting the contention that either O’Malley ripped the franchise from the bosom of a borough that has never recovered its identity or self esteem, or that Moses did not understand the value of keeping the Dodgers in Brooklyn and was unnecessarily obstinate when it came to reaching a mutually satisfactory agreement with O’Malley to keep the team in the city. The purpose of this article is to provide a more dispassionate account without the assigning of blame and arrive at some conclusions regarding what choices O’Malley had to make when he brought major league baseball to Southern California.

From 1946 through 1957 the Brooklyn Dodgers won more games than any other franchise in the National League[fn]1958 Los Angeles Dodger Yearbook, 43. [/fn] and were arguably the loop’s most exciting team. Only the Yankees won more. The Dodgers were loaded with diverse and interesting personalities who immersed themselves in the community, and the core players were virtually constant over that entire period. A decade or more of success with basically the same crew meant one thing; on-field personnel were getting too old to maintain a championship level of play. By 1957 Pee Wee Reese was 38, Roy Campanella 35, Carl Furillo 35, Sal Maglie 39, Gil Hodges 33, and even the relative youngsters, Duke Snider, Carl Erskine, and Don Newcombe, were past 30.[fn]http://www.baseball-reference.com. [/fn]

In early 1957 Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale were nothing more than promising youngsters; Johnny Podres was in the Navy; Maury Wills, John Roseboro, and Tommy Davis were minor leaguers; Wally Moon was a Cardinal; Ron Fairly and Frank Howard were in college; and Willie Davis hadn’t finished high school. With all due respect to Brooklyn’s regular second baseman Jim Gilliam, he was hardly a cornerstone franchise player. No one could have known that this group would dominate the National League from 1962 through 1966.

In early 1957 Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale were nothing more than promising youngsters; Johnny Podres was in the Navy; Maury Wills, John Roseboro, and Tommy Davis were minor leaguers; Wally Moon was a Cardinal; Ron Fairly and Frank Howard were in college; and Willie Davis hadn’t finished high school. With all due respect to Brooklyn’s regular second baseman Jim Gilliam, he was hardly a cornerstone franchise player. No one could have known that this group would dominate the National League from 1962 through 1966.

It’s one thing to lose games and quite another to struggle with the balance sheet when baseball is the family business. In Brooklyn, the history was either contention or bankruptcy. When the team went twenty years between pennants before 1941, it landed in receivership and major decisions were being made or influenced by The Brooklyn Trust Company.[fn]Forever Blue, 38. [/fn] Attendance dipped under 500,000 five times during this period.[fn]1980 Baseball Dope Book, 71–72. [/fn]

Walter O’Malley was also justified in considering a move from Ebbets Field. By 1957 the right field screen hung in tatters, the bathroom odors were stifling, and parking was available for only 700 cars.[fn]After Many a Summer, 66–67. [/fn] In 2003 Buzzie Bavasi wrote, “Ebbets Field was a great place to watch a game if you were sitting in the first 12 rows between the bases. Otherwise, we had narrow seats, narrow aisles, and a lot of obstructed views.”

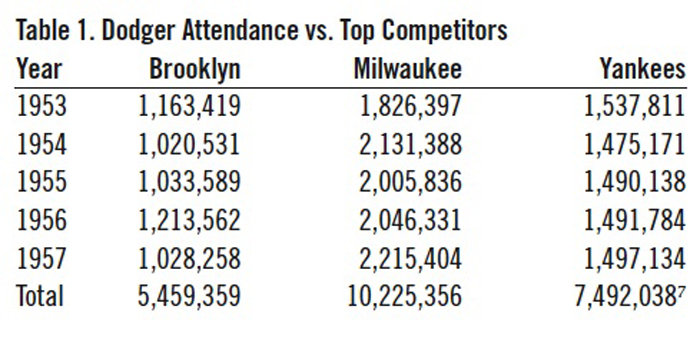

Mid-1950s attendance compared with the Dodgers’ primary rivals of that time was also disturbing. From a high of 1.8 million in 1947,[fn]Ibid, 72. [/fn] as the team won five more pennants and finished second three other times, Dodger attendance dwindled. When the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee before the 1953 season, a worrisome situation grew dire.

Lower attendance compared with the primary competition meant fewer concessions sold, less money available for player procurement and development, and was perhaps a sign of waning interest. On the last Wednesday of the 1956 season, with the defending World Champions one-half game out of first place, the day after Maglie had thrown a no-hitter, the Dodgers drew 7,847 to Ebbets Field.[fn]http://www.retrosheet.org. [/fn] Player procurement would be more important than ever as the team rebuilt, and O’Malley would have been justified in worrying that he wouldn’t have the cash to compete.

But wait, O’Malley critics claim the Dodgers were profitable during this period. They are right, but the claim is not as straightforward as it might seem. In 1955, for example, the Dodgers earned $787,155 from WOR TV.[fn]The Dodgers Move West, 35. [/fn] They accomplished that by televising all home games and twenty road games. Yet, in August 1955, Yankees owner Dan Topping was working hard to convince O’Malley and Giants owner Horace Stoneham to curtail or eliminate the practice of televising home games. O’Malley was receptive, in part because he believed the televising of home games cut into concession revenue, casting doubt on the net profit of the WOR deal.[fn]After Many a Summer, 145. [/fn] That income was crucial to the franchise’s profitability.[fn]The Dodgers Move West, 68. [/fn] The importance O’Malley placed on concession revenue could be seen in his willingness to make every Saturday home date a Ladies’ Day in 1956 and 1957, when female fans were admitted at no charge.[fn]Brooklyn Dodger Yearbooks, 1956, 48; 1957, 47. [/fn] Brooklyn’s net income from 1952–1956 ranged from a low of $209,979 in 1954 to a high of $487,462 in 1956 when Brooklyn hosted four World Series games.[fn]The Dodgers Move West, 69. [/fn] With an aging, deteriorating team and ballpark, slipping attendance, and the TV revenue in question, there was plenty of cause for concern in the Dodgers business office.

Another element of the profitability question has to do with Walter O’Malley’s vision for his franchise. He needed profits to help build a new ballpark, regardless of where it was located. A new ballpark was his best chance of continuing to compete well in a three- or even a two-team market given that fans were staying away from Ebbets Field despite the winning ways of the team on the field. If fewer games were made available to television, and ticket and concession revenue declines were not reversed, it was debatable how much longer the franchise would be viable playing at Ebbets Field.

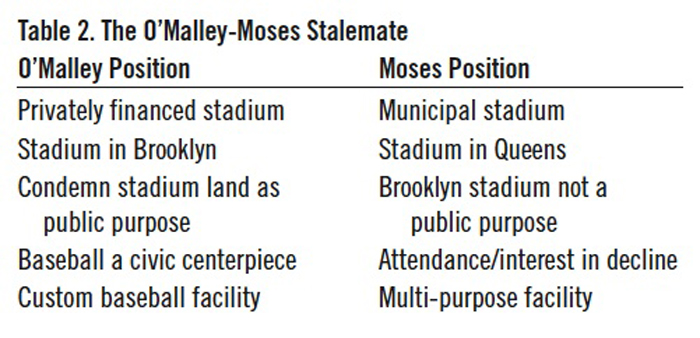

O’Malley was a devout capitalist, and that no doubt drove him. Yet finances were not his only problem. To build a new stadium in Brooklyn, he needed a cooperative city government. That’s where he ran up against Robert Moses. As the head of many public agencies, including the cash cow Triborough Bridge Authority, Moses was the most powerful public works administrator in New York City. By all accounts, his influence was far-reaching and abundant … and he and O’Malley did not see eye-to-eye on the Dodgers’ needs. In divorce court this dichotomy might be classified as “irreconcilable differences.” Moses’s influence was such that nothing as significant as a major league stadium could be built without his cooperation and approval. O’Malley owned the Dodgers, and his primary recourse was to move the franchise. Moses and Mayor Robert Wagner did not believe that the political fallout from losing National League baseball would be enough to cost them power. They were proved right about that. Wagner’s opponent in the November 1957 mayoral election, held about six weeks after the Dodgers and Giants played their last games in New York and well after their exodus had been confirmed, received fewer votes than Wagner’s 1953 opponent. Brooklyn voters, meanwhile, gave Wagner a plurality of more than 330,000 votes.[fn]After Many a Summer, 328. [/fn] A reasonable person might wonder how much the typical Brooklyn resident cared about retaining the Dodgers. Moses did not face elections and retained enough influence to remain in power well into the next decade. The two had simply read the tea leaves and determined that there was no pressing need to keep the Dodgers and Giants in New York on anything other than the city’s terms.

O’Malley was a devout capitalist, and that no doubt drove him. Yet finances were not his only problem. To build a new stadium in Brooklyn, he needed a cooperative city government. That’s where he ran up against Robert Moses. As the head of many public agencies, including the cash cow Triborough Bridge Authority, Moses was the most powerful public works administrator in New York City. By all accounts, his influence was far-reaching and abundant … and he and O’Malley did not see eye-to-eye on the Dodgers’ needs. In divorce court this dichotomy might be classified as “irreconcilable differences.” Moses’s influence was such that nothing as significant as a major league stadium could be built without his cooperation and approval. O’Malley owned the Dodgers, and his primary recourse was to move the franchise. Moses and Mayor Robert Wagner did not believe that the political fallout from losing National League baseball would be enough to cost them power. They were proved right about that. Wagner’s opponent in the November 1957 mayoral election, held about six weeks after the Dodgers and Giants played their last games in New York and well after their exodus had been confirmed, received fewer votes than Wagner’s 1953 opponent. Brooklyn voters, meanwhile, gave Wagner a plurality of more than 330,000 votes.[fn]After Many a Summer, 328. [/fn] A reasonable person might wonder how much the typical Brooklyn resident cared about retaining the Dodgers. Moses did not face elections and retained enough influence to remain in power well into the next decade. The two had simply read the tea leaves and determined that there was no pressing need to keep the Dodgers and Giants in New York on anything other than the city’s terms.

In Twilight Teams, his excellent accounting of post-war major league baseball franchise shifts through 1971, author Jeffrey Saint John Stuart makes the point that generally the new city made more attractive offers than the city from which a team was leaving. While Moses, Wagner, and other officials dithered in New York, Mayor Norris Paulson, Supervisor Kenneth Hahn, and Councilwoman Rosalind Wyman put together an offer in Los Angeles that was too attractive for O’Malley to dismiss. Space limitations preclude a detailed accounting of that offer, but suffice to say that the Dodgers wound up in 1962 with a privately owned, 56,000-seat stadium at the confluence of several major freeways[fn]Los Angeles Dodger Yearbook 1962, cover. [/fn] surrounded by 16,000 parking spaces.[fn]Ibid, 3. [/fn] Dodger Stadium remains functional and attractive to this day. Moses’s vision, which turned into Shea Stadium in 1964, “looked old the day it opened,” according to New York sportswriter Leonard Koppett. Shea was closed after the 2008 season and torn down that winter.

Those who have complained the longest and the loudest about O’Malley (primarily Dick Young, Dave Anderson, and Roger Kahn) were New York sportswriters left with less to cover. Rumblings about a move out of Brooklyn had begun in 1953,17and Dodgers fans had responded by attending fewer games despite the team’s success. New York officials were circumspect in their dealings with the Dodgers, while Los Angeles politicians were highly cooperative, if not downright accommodating. On top of all that, moving to Los Angeles meant that O’Malley would have the third largest city in the United States all to himself in terms of major league baseball.

If one views a baseball franchise as a public trust, then a case can be made that the Dodgers should have stayed in Brooklyn and taken what they could get in New York. If one views owning a baseball franchise as a competitive, profit-driven enterprise, then moving to Los Angeles was probably the best baseball-related gift O’Malley could give his family. In this case, at that time, for this author, the offer to move to Los Angeles made too much sense for O’Malley to ignore. The situation in Brooklyn was deteriorating and looked to get only worse, at least in the short term. It would have been an act of irresponsibility towards his stockholders and his family to remain in Brooklyn.

Despite all the finger-pointing over the past 54 years, it is very possible that there is no villain in the case of the Dodgers relocating to Southern California. It may be nothing more than reasonable people with understandable motivation responding rationally to a unique set of circumstances.

PAUL HIRSCH is the owner of Paul Hirsch Professional Communications, a marketing and public relations firm in Danville, California, where he lives with his wife Debbie and two children. Paul has been a SABR member since 1983, is a past president of the Lefty O’Doul chapter, and has served on the SABR Board of Directors since 2007. His work has been published in BioProject books on the 1969 Mets and 1947 Dodgers.

Sources

- The 1980 Baseball Dope Book. The Sporting News. 1980.

- Brooklyn Dodger Yearbooks, 1956–1957.

- D’Antonio, Michael. Forever Blue. Riverhead Books. 2009.

- Fetter, Henry D. Revising the Revisionists, Walter O’Malley, Robert Moses, and the End of the Brooklyn Dodgers, New York History, Winter 2008.

- Goldblatt, Andrew. The Giants and the Dodgers. McFarland & Co. 2003.

- Golenbock, Peter. Bums; An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Putnam. 1984.

- Kahn, Roger. The Boys of Summer. Harper and Row. 1971.

- Kahn, Roger and Al Helfer. The Mutual Baseball Almanac. Doubleday & Co. 1954.

- Los Angeles Dodger Yearbooks, 1958–1962.

- McGee, Bob. The Greatest Ballpark Ever. Rutgers University Press. 2005.

- Moses, Robert. The Battle of Brooklyn, Sports Illustrated. 22 July 1957.

- Murphy, Robert E., After Many a Summer. Union Square. 2009.

- Schiffer, Don editor, The Major League Baseball Handbook, 1961. Thomas Nelson & Sons 1961.

- Stuart, Jeffrey Saint John, Twilight Teams. Sark Publishing, 2000.

- Sullivan, Neal, The Dodgers Move West. Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Baseball-reference.com.

- Retrosheet.org.

- WalterOMalley.com.

- Personal conversation with Leonard Koppett, 2002.

- E-mail exchanges with Buzzie Bavasi, 2001–2008.