Was Ty Cobb a Power Hitter?

This article was written by Roy E. Brownell II

This article was published in 2006 Baseball Research Journal

Ty Cobb is usually thought of as the very embodiment of the Deadball Era hitter; the “Punch and Judy” counterpoint to the post-1920 Ruthian power game.1 This common misconception is underscored in a number of ways.

First, it is supported by the types of players who have surpassed Cobb’s career records. Lou Brock bested his lifetime stolen base record, Pete Rose his career hit mark and Rickey Henderson his modern record for total runs scored. Other recent players frequently compared to Cobb are high-average contact hitters such as Wade Boggs, Rod Carew, Tony Gwynn and Ichiro Suzuki. These players have been either speedsters, contact hitters or both and none is known for his power hitting (with the possible exception of Henderson).

Because of the natural tendency to place players from a different era into a familiar, contemporary context, Cobb’s ability to steal bases, collect base hits, score runs and hit for high average has led to some misleading comparisons; which contribute to the view that Cobb could not and did not hit for power.2

Second, Cobb’s open contempt for the Ruthian power game has done little to dispel this modern misconception. Cobb much preferred baseball the way it was played during the Deadball Era. Cobb’s approach to batting involved him choking up, holding the bat with his hands apart, and hitting to all fields, often just pecking at the ball.3

Third, Cobb’s Deadball home run totals appear quaint compared to Lively ball era totals and seem to bespeak a contact hitter’s batting style. By averaging less than five home runs a season—a good week’s work for today’s sluggers—Cobb’s home run output on its face seems to confirm his lack of power.

The perception of Cobb as solely a contact hitter has long been in need of revision. Contrary to contemporary myth, Cobb could indeed hit for power and, while he might not be properly characterized as a power hitter during his prime, he could (and did) hit for power more effectively than the majority of his contemporaries. There are a number of factors that point to this conclusion. They include: (1) his actual home run hitting, which has long been overlooked; (2) his ability to collect extra-base hits; (3) his prolific slugging average and total base output; and (4) his ability to drive in runs.

Cobb’s Home Run Hitting

Cobb spent the majority of his career playing in the Deadball Era, when home runs were a rarity and those that were hit were much more apt to be of the inside-the-park variety. Within the confines of the Deadball Era, Cobb displayed impressive power. He led the major leagues with nine home runs in 1909, establishing a team record unsurpassed in the Deadball Era. Leading one league in home runs (let alone both) is a feat that certainly eluded purported modern-day “Cobb prototypes” such as Brock, Rose, Henderson, and the like. Moreover, to claim this honor, Cobb had to out-homer some distinguished sluggers. They included the likes of Harry Davis, “Home Run” Baker, and Sam Crawford, who won 10 league home run crowns between them.

Nor was Cobb’s 1909 home run total a fluke. He finished runner-up or tied for runner-up in the AL in home runs on three occasions (1907, 1910, and 1911), seven times in the top five, and 11 times in the top ten.4 In fact, one of his top-ten finishes occurred in 1921, during the Lively ball era. Cobb even out-homered entire teams. For each of three straight years (1908–1910) Cobb hit more home runs than the Chicago White Sox, a feat he replicated in 1917 by out-homering the Washington Senators. Cobb also led his team in home runs six times—no small feat playing next to Crawford, Bobby Veach, and Harry Heilmann.

It could, of course, be argued that since 46 of Cobb’s 117 career round-trippers were inside-the-park, his home run totals reflect more speed than power. Proponents of this outlook could point out, for example, that in 1909 all of Cobb’s home runs were inside-the-park jobs (tying an AL record for most inside-the-park home runs in a season).5 Since all his home runs were inside-the-park, the logic goes, Cobb must not have hit for power. There are, however, at least four reasons why such a position is fundamentally flawed.

First, Cobb hit a good number of out-of-the-park home runs. Excepting 1909, approximately one half of his career Deadball Era circuit clouts were out-of-the-park home runs. In fact, Cobb frequently ranked among the league leaders in out-of-the-park home runs, thus belying the notion that his home run totals were solely the product of speed. Cobb finished third in the league in out-of-the-park home runs in 1907, tenth in 1910, fourth in 1911, second in 1912, tenth in 1917, and eleventh in 1925. His six out-of-the-park home runs in 1912 set a team record at the time, and Cobb led or was second on his team in this category on seven occasions.

Second, if speed were the only factor involved in finishing among the league home run leaders during the Deadball Era, then why did Clyde “Deerfoot” Milan never have a top-ten finish? Why could neither Max Carey nor Eddie Collins muster more than one top-ten finish each? The answer is essentially that Milan, Carey, and Collins had the speed but not the power. Cobb had both.

Third, viewing Deadball inside-the-park home runs as solely a reflection of speed projects mod- ern-day notions of inside-the-park home runs back to the Deadball Era. During that period the field of play was generally much larger than it is today. Cobb played 15 years in Detroit’s Navin Field, which had its right-field fence 370 feet from home plate and its center-field fence 467 feet away (as opposed to 325 and 440 feet, respectively, when Tiger Stadium closed in 1999).6 The extra 45 feet in right field and 27 feet in center field almost certainly cost Cobb a good share of out-of-the-park home runs. Because of these inhospitable dimensions, in 15 years playing in Navin Field, Cobb hit just 16 home runs.7

Not only was hitting out-of-the-park home runs rare during the Deadball Era, but hitting inside-the-park home runs could be difficult as well. If the crowd was large enough, fans were often permitted to view the game from standing-room-only sections placed on the outfield grass. Balls hit over the outfielders’ heads into these sections, which might have been inside-the-park home runs without the crowd or out-of-the-park home runs in today’s ballparks, were frequently ruled only ground-rule doubles or triples, thus costing the hitter home runs.

Fourth, Cobb’s home run hitting during the Lively ball era reinforces the view that his home run totals were not merely the product of his speed. During the Lively ball era—when Cobb began to hit home runs more frequently—only six of his 50 home runs were of the inside-the-park variety. In 1925, Cobb finished 11th in the American League with 12 home runs, none of which was an inside-the-park job.8 Clearly, during the Lively ball era, Cobb was not relying on speed for his home runs— he was hitting the ball out of the park.9 Knowing Cobb’s stubborn refusal to change his style of play, the most plausible explanation would seem to be that Cobb was hitting as he always had—often with punch but with the added benefit of liveball conditions.

Comparison of Cobb’s Home Run Hitting Across Historical Eras

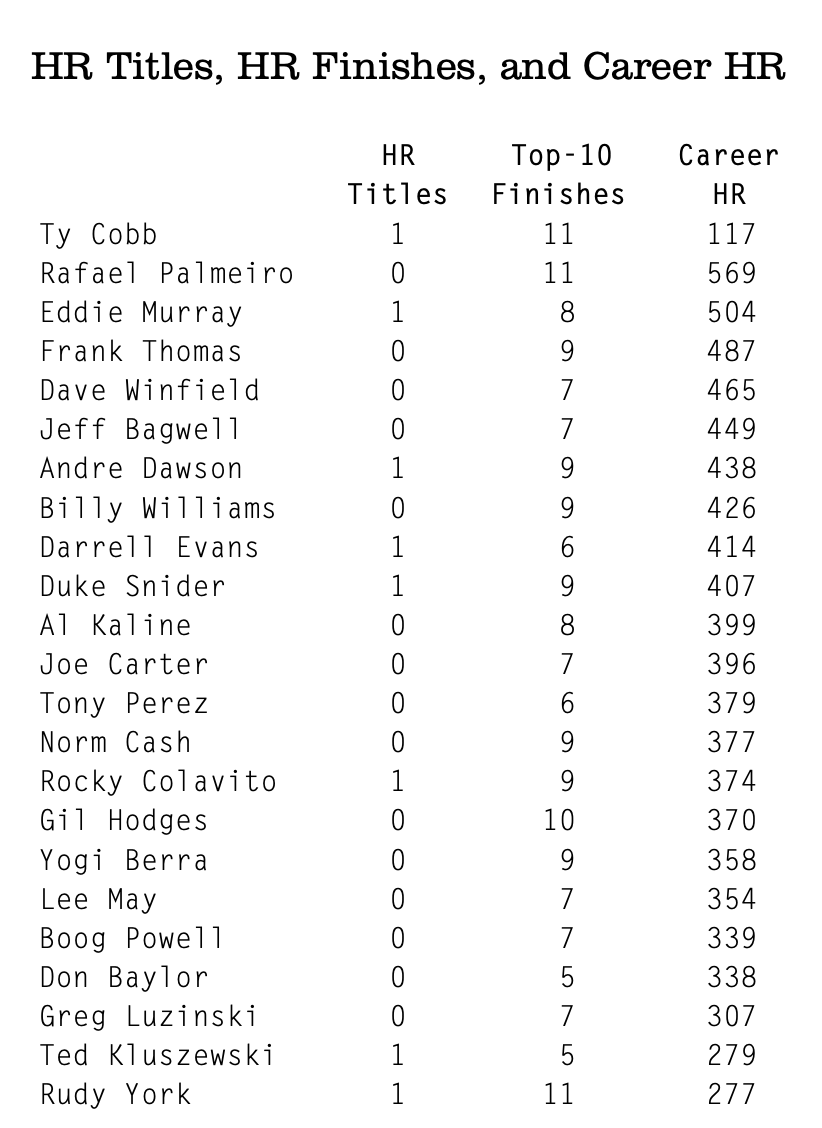

The number of times Cobb finished in the top ten in home runs is worthy of some elaboration. Consider the following chart.10 The players listed in it are generally considered sluggers. Cobb’s home run title and 11 top-ten finishes compare favorably against these Lively ball power hitters, even allowing for the fact that expansion has increased the number of players in the modern era.

Cobb, of course, was not a greater slugger than Eddie Murray or Ted Kluszewski. Nonetheless, this chart does reflect that Cobb did hit for power and, within the context of his time, he did so more effectively than many players traditionally viewed as power hitters.

More elaborate quantitative efforts have been undertaken to compare players across historical eras, and these studies confirm Cobb’s home-run hitting. G. Scott Thomas, for example, has recalibrated player statistics as if they had played from 1996 to 2000. While one should not lose sight of the fact that projections are not hard numbers, and as such should not be relied upon unduly, it is worth noting that under Thomas’ formula, Cobb’s career adjusted home runs are 587, ranking him 25th on his list. Among those players who spent most of their career before 1920, Roger Connor is the only player ahead of Cobb.11

Michael Schell lays out his own statistical model that also permits comparison of player statistics across eras. Schell’s model computes Cobb’s adjusted home run total for an average season to be 22,12 tying him with Don Baylor, Darrell Evans, Andre Thornton, and Jim Rice. Among players who spent the majority of their career before the Lively ball era, Cobb is tied with Honus Wagner, Tilly Walker, and Joe Jackson and finishes ahead of Harry Davis, Connor, Sam Thompson, and Dan Brouthers. By contrast, under Schell’s model, other Deadball speedsters do not fare nearly as well as Cobb. Collins’ home runs are recalculated at nine, Carey at 13, and Milan at five.13

Schell also projects Cobb’s adjusted career home run total to be 418, 29th on his list, trailing only Crawford among players who completed most of their playing days before 1920.14 These are all projections, to be sure, but they do reinforce the notion that Cobb could hit for power.

It is worth remembering that prior to 1920 the threshold for hitting a high number of career home runs was not 500 but 100. During this period only ten players reached the 100 home run plateau. Going into the 1920 season—not quite two-thirds of the way through his career—Cobb had 67 home runs, well on his way toward the 100 threshold.

As noted by Cobb’s first full-length biographer, while his career home run total did

not begin to equal Ruth’s record . . . it must be remembered that in this respect Ruth stands in a class by himself. As compared with the home-run records of other great stars of the diamond in days gone by or with those of today’s heroes, Ty’s record looms large on baseball’s horizon. He is one of the few players who have driven out more than 100 homers in a life time.15

After his final season, Cobb was tied for 16th on the all-time home run list.16

The Views of Cobb’s Contemporaries

Deadball Era players and observers recognized Cobb’s ability to hit for distance. Charles Comiskey, owner of the Chicago White Sox, wrote of Cobb in 1910 that he is “able to hit the ball further away than the majority of ‘cleanup’ hitters.”17 Rube Bressler observed, “Cobb could hit the long ball—when he wanted to. Of course, that dead ball . . . we didn’t have a baseball to hit in those days. We had a squash. . . . Still, Cobb could hit them a distance when he wanted to.”18 Joe Sewell stated, “Ruth hit all those home runs, but Cobb could whack the ball as hard as anyone.”19 Tris Speaker noted that Cobb “can bunt, chop-hit, deliver long drives, or put balls out of sight.”20

Heilmann said of Cobb: “Cobb was always, by preference, a place hitter. People never figured him as a slugger, but he could have been a dangerous slugger if he had set out to be. He is now, when he feels in the mood. But when he sets out to slug the ball, he takes a big stride forward and wades right in.”21 A prominent baseball writer observed in 1922, “Ty be it noted, is not primarily a slugger….He does slug oftentimes and to some purpose. His doubles are many and his homers total up to impressive figures.”22

Cobb himself stated in the early 1920s:

[i]f I had set out to be a home run hitter, I am confident that in a good season I could have made between twenty and thirty home runs. True, I couldn’t hope to challenge Babe Ruth in his specialty. But I do feel that I could have made an impressive number of homers if I had set out with that end in view. . . . My idea of a genuine hitter is a hitter who can bunt, who can place his hits and who, when the need arises, can slug.23

Anecdotal Evidence of Cobb’s Power Hitting

Anecdotal evidence reinforces the view that Cobb could hit for power when he so desired. The most famous example occurred in May 1925 in St. Louis. Fed up with hearing about Babe Ruth’s power game (and no doubt alert to a breeze blowing out to right field),24 Cobb reportedly informed the press: “I’ll show you something today. . . . I’m going for home runs for the first time in my career.”25 That day Cobb hit three home runs—tying an American League record at the time—and launched a double to the far reaches of right-center field.26 Cobb hit two more home runs the following day, drove another ball to the wall, and came within a foot of yet another home run the next game, settling for a double.27 Cobb’s five home runs in consecutive games (all out-of-the-park home runs) tied a major league record, a mark subsequently equaled but never surpassed. As Cobb’s premier biographer reflected,

[this] home run outburst marked no new, power-oriented phase in Cobb’s career. . . . He still loved the old game, still preferred most of the time just to ‘nip’ at the ball, as Walter Johnson had once described his hitting style. But he could also clout with the musclemen when he chose. It was a question of how the game ought to be played.28

On September 30, 1907, with the American League pennant going down to the wire, Cobb’s Detroit Tigers faced off in a pivotal and long-remembered game in Philadelphia against the Athletics. The Tigers trailed 8–6 going into the top of the ninth. With a runner on first, Cobb stepped in against future Hall of Famer Rube Waddell. Cobb sent Waddell’s second pitch over the right-field wall to send the game into extra innings.29 Ultimately, the game was called for darkness after 17 innings, the Athletics were deprived of a key victory (there being no makeup games), and the Tigers went on to win their first of three consecutive American League crowns. Of the home run, one author wrote: “It was just another case of Cobb doing what he wanted when he wanted.”30 Incidentally, that home run was one of five Cobb hit that year, almost half of the Tigers’ team total of 11.

He was also known to hit tape-measure blasts. In 1907, against another future Hall of Famer, Addie Joss, Cobb stroked one of the longest home runs hit up to that time at Cleveland’s League Park.32 Five years later, again at League Park, Cobb hit another shot that may have matched or even exceeded the length of his 1907 effort.33 In 1917, in Boston, Cobb drilled a pitch into the center-field stands, a spot reached before only by Ruth.34 That same year in St. Louis, Cobb drove a home run ball over 500 feet, thought to have exceeded prior tape- measure shots by Jackson and Ruth.35

Cobb’s home-run hitting exploits should not be all that surprising considering that he matured to reach over six feet tall and weigh approximately 190 pounds, a good-sized player for the time.

Cobb’s Ability to Hit for Extra Bases

During the Deadball Era, home runs were only one indication of power hitting. Extra-base hits help to provide a fuller picture of a player’s slugging ability. At the time of his retirement, Cobb was the all-time leader with 1,136 extra-base hits. He still ranks tenth on the all-time list.

Cobb led the league in extra-base hits three times and finished either second or third on four other occasions. His 79 extra-base hits in 1911 were the highest of the Deadball Era, and his 74 extra- base hits in 1917 the fifth highest.

Cobb’s output of doubles and triples was prolific. Cobb ranks fourth all-time in doubles, having led the league three times in this category. Cobb is second all-time in triples, a statistic he led the league in on four occasions. Triples, of course, were “the real power statistic of the dead-ball era.”36 Today, batters who hit large numbers of triples are generally speedsters who hit balls in the gaps and can turn doubles into three-base hits. In the Deadball Era, with its larger fields of play, triples (as with inside-the-park home runs) were more apt to come from batters, like Cobb, who could hit the ball far enough to get it past outfielders and mobile enough to get to third quickly.

Cobb’s Slugging Average and Total Bases Output

Slugging average is traditionally viewed as a key indicator of power hitting (hence its name). Cobb led the league eight times in this category and finished second or third on six other occasions.37 Only Ruth, Ted Williams, and Rogers Hornsby led the league in slugging average more often.

Despite playing most of his career in the Deadball Era, Cobb posted impressive slugging figures. Cobb’s .621 slugging average in 1911 was the third highest mark of the Deadball period, and his .584 slugging average in 1912 the sixth highest.

Nor did Cobb’s success in slugging average end with the advent of the Lively ball. Cobb racked up three top-ten finishes in slugging in the 1920s despite being at the end of his career. Furthermore, his career slugging average—despite 15 Deadball seasons—is higher than a number of liveball sluggers such as Harmon Killebrew, Jim Rice, Ernie Banks, Frank Howard, Eddie Mathews, Reggie Jackson, Dave Winfield, and Dave Kingman, to name just a few. Needless to say, Cobb’s career slugging average exceeds those of Rose, Brock, Henderson, Carew, Boggs, Gwynn, and Suzuki (none of whom has ever led the league in this category). Finally, it bears mentioning that Thomas’ statistical formula ranks Cobb 10th in adjusted career slugging average38 and Schell’s formula 14th.39

Cobb’s total base output is also impressive. Cobb led the league in this category six times, an American League record he shares with Ruth and Williams. Only Hank Aaron and Hornsby led the league more often. Nine other times Cobb finished in the top ten in this category, including three times during the 1920s. His 367 total bases in 1911 were the second most ever prior to the Lively ball era. Even today, Cobb remains fourth all-time in career total bases.

Cobb’s Ability to Drive In Runs

Runs batted in is another category typically viewed as an indicator of a slugger’s prowess. Cobb was a prolific RBI man. He ranks sixth all-time in career RBI, led the league four times, and had 13 seasons in the top ten. In fact, four of those top-ten finishes occurred during the power-happy 1920s. Cobb’s 127 RBI in 1911 set an American League record at the time and were the third highest of the Deadball Era.

It should hardly be surprising that a hitter of Cobb’s caliber was so effective at driving in runs since Cobb batted third or clean-up throughout most of his career.40 That is noteworthy in and of itself since modern “Cobb prototypes” have typically not batted in the middle of the order but tended to hit first or second.

Conclusion

Ty Cobb was not a power hitter per se, any more than George Brett or Stan Musial were principally power hitters. Nonetheless, Cobb could and did hit for power, a point that should not be lost on students of baseball history.

ROY BROWNELL II is an attorney. He lives in Washington, D.C., with his wife Sandy.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the residents of Ty Cobb Avenue for their support and Jim Charlton, Ron Cobb, Scott Flatow, David Stephan, Tom Simon, and David Vincent for their invaluable critiques of this paper. Any errors remain the author’s alone.

Notes

1. Donald Honig. Baseball America 232 (1985) (“Ty did not hit with power”).

2. William Curran. Big Sticks 203 (1990) (“During . . . Pete Rose’s pursuit of Cobb’s lifetime record for base hits . . . . [m]any young fans may have been left with the impression that the Georgian had been little more than an ill-tempered singles hitter”).

3. Charles C. Alexander. Ty Cobb 90 (1984). Cobb denied that his approach to hitting cost him power. “’Loss of power’ remains the criticism against spread hands hitting. The truth is that the mania for killing the ball has replaced common sense. ‘Power’ is not just producing home runs.” Cobb continued: “Loss of power through choking up? The statement is laughable. . . . there was power aplenty in my style of holding a bat.” Ty Cobb, My Life in Baseball, 148–49 (1993 ed.).

4. See www.Baseball-reference.com for all single-season and career rankings.

5. Inside-the-park and home/away home run statistics come from SABR’s The Home Run Encyclopedia. See SABR, The Home Run Encyclopedia, 56 (1996). Inside-the-park home run totals are subject to periodic updating as ongoing research unearths new data.

6. www.baseball-almanac.com/stadium/tiger_stadium.shtml.

7. Bill James compared Cobb’s home run hitting to that of the celebrated Deadball slugger Gavy Cravath, noting that Cravath played in homer-happy Baker Bowl while Cobb languished in Navin Field. James points out that Cobb more than tripled Cravath’s career road home run output (82–26). See The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, 102 (2001). One can only speculate as to how Cobb’s home run statistics might have looked had he played in Baker Bowl with its right-field fence only 273 feet from home plate (97 feet closer than in Navin Field). Philip S. Lowry, Green Cathedrals, 173 (2006).

8. Home Run Encyclopedia, supra note 5, at 387.

9. The author thanks Tom Simon for raising this point.

10. The statistics in the table are taken from www.Baseball-reference.com.

11. G. Scott Thomas. Leveling the Field, 256 (2002).

12. Michael J. Schell. Baseball’s All-Time Best Sluggers, 360 (2005).

13. Ibid. at Appendix N.

14. Ibid. at 334.

15. Sverre O. Braathen. Ty Cobb: The Idol of Fandom, 184 (1928).

16. The ranking is derived from Steve Nadel & Mike Caragliano’s “All-Time Home Run List.”

17. Marc Okkonen. The Ty Cobb Scrapbook, 227 (2001).

18. Lawrence S. Ritter. The Glory of Their Times, 204–05 (1984 ed.).

19. Robert Obojski. Baseball’s Strangest Moments, 78 (1988).

20. Al Stump. Cobb, 363 (1996).

21. Harry Heilmann. “When you slug, step into the ball,” 38 Baseball Magazine, 438 (March 1927).

22. F.C. Lane. “Natural Slugging vs. Scientific Batting,” 29 Baseball Magazine, 388 (August 1922).

23. Ibid. at 388–89.

24. Okkonen, supra note 18, at 192.

25. Alexander, supra note 3, at 175.

26. Dan Holmes. Ty Cobb: A Biography, 103 (2004).

27. See ibid.

28. Alexander, supra note 3, at 176.

29. John Thorn. Baseball’s Ten Greatest Games, 17–19 (1981).

30. Glenn Dickey. The History of the American League, 24 (1980).

31. Okkonen, supra note 17, at 8.

32. Ibid. at 78.

33. Ibid. at 118.

34. Stump, supra note 20, at 260; Okkonen, supra note 18, at 119.

35. Thomas Gilbert. Dead Ball: Major League Baseball Before Babe Ruth, 27 (1996).

36. Cobb’s slugging titles were no mere reflection of his high batting average. Cobb led the league in Isolated Power five times. See The Sabermetric Baseball Encyclopedia. Isolated power is computed by subtracting batting average from slugging average, thus “isolating” extra-base hitting. Only Ruth, Williams, Mike Schmidt, and Barry Bonds have led the league more often in this category. The author wishes to thank Tom Simon for raising this issue.

37. Thomas, supra note 12, at 268.

38. Schell, supra note 13, at 348.

39. David Jones, ed. Deadball Stars of the American League. SABR, 2007. 529-530.