When Defeat is not a Loss: The 1967 World Series

This article was written by Glenn Stout

This article was published in 1967 Boston Red Sox essays

1967 was, perhaps, the last time the Boston Red Sox entered postseason play without either the burden or curse of history, perhaps the last time they played to beat only one team and not bring down an entire legacy.

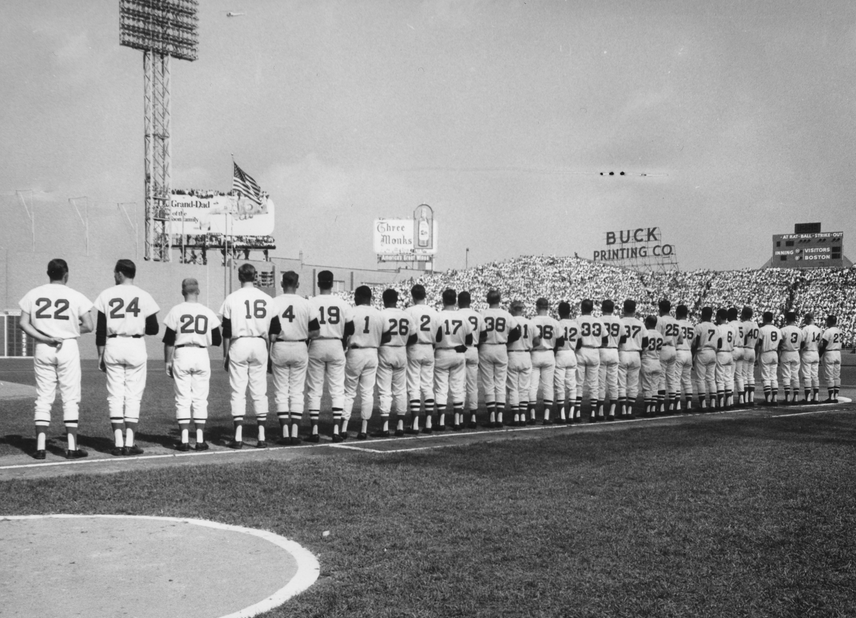

The Impossible Dream Team introduced as the 1967 World Series begins. (BOSTON HERALD)

It was, perhaps, the last time the Red Sox entered postseason play without either the burden or curse of history, perhaps the last time they played to beat only one team and not bring down an entire legacy. From the Boston perspective, when the Red Sox and Cardinals met in the 1967 World Series there was no expectation either of impending doom or certain victory. No one in the press hearkened back to the heartaches of 1948, or 1946, or any other year. If the 1967 regular season had taught the Red Sox and their fans anything, it was that the story of the 1967 Sox was the journey itself, the crazed elevator ride of emotions that over the course of a season had introduced a new generation of fans to the Red Sox. On the precipice of the Series, all anyone knew now was that, for better or worse, the Series marked the end of the ride. The only question that remained was, win or lose, whether or not anyone’s heart could take it.

At the start of the Series, all logic pointed to a Cardinals victory. They were the experienced, veteran club of established stars like Orlando Cepeda, Lou Brock, and Curt Flood, a team that had steamrolled to the National League pennant by 10½ games despite being without ace Bob Gibson for seven weeks after he stopped a Roberto Clemente line drive with his shin. He was healthy now and, with only 175 innings on his arm, fresh. Moreover, the Cardinals had weeks to rest and set up their pitching rotation.

The Red Sox, meanwhile, had ridden the elevator up and down at breakneck speed for weeks, going from the lowest of lows, like the beaning of Conigliaro, to the highest of highs, like Jose Tartabull’s game-saving throw a little over a week later that launched the Red Sox into first place. In the end, the elevator screeched to a halt and when the door suddenly opened the Red Sox tumbled out and found themselves alone on the top floor, American League champions. They were simultaneously exhilarated, exhausted, and ecstatic. So were their fans.

The logic that indicated a St. Louis victory appeared trumped by the accumulated magic and mojo that had been in evidence almost nightly over the past six months. The improbable and impossible had somehow won, and so, it seemed to almost everyone in Boston, would the Red Sox.

The Series opened in Boston and Game One featured Gibson opposite Jose Santiago. In the third inning, the Cardinals scored first after Brock singled, Flood spanked a double, and Maris knocked Brock home with a ground ball. That was predictable – elevator going down. But so was what came next. Jose Santiago, of all people, cracked a home run off Gibson and everyone piled back on the elevator going up.

That woke Gibson up, and he shut the Sox down from there. Brock scored another run in much the same fashion to give the Cardinals a 2-1 win.

The Sox turned to Lonborg in Game Two and Lonborg turned to superstition, wearing his lucky mismatched spikes, spending the night in a downtown hotel and carrying a gold paper horseshoe in his back pocket that had been sent by a fan. He stopped Brock with a dose of reality in the first inning, knocking him to the ground, then let the magic happen.

He was perfect. Yaz cracked two home runs and the Sox opened up a 5-0 lead entering the eighth inning. The Cardinals hadn’t even had a hit yet and the elevator threatened to go through the roof and disappear from sight. Four outs away from immortality, Julian Javier rapped a double to left to return Lonborg to mere legendary status. The Sox won 5-0 and the Series was tied.

Both teams withdrew to St. Louis for Game Three. The Cardinals brought the Red Sox back to earth with a tidy 5-2 win as they knocked out Gary Bell in the third and Nelson Briles went the distance to win. It was more of the same in Game Four. This time Jose Santiago was the victim. He never got out of the first inning as St. Louis exploded for four runs, three more than Gibson needed. This time he shut out the Red Sox on five hits to win 6-0.

Now all that stood between the Red Sox and 1968 was Jim Lonborg. That was plenty as the eventual Cy Young Award winner sent Boston hearts soaring with a three-hitter, setting a record for the fewest hits allowed in back-to-back Series starts, as Boston won 3-1.

When the Red Sox returned to Boston’s Logan Airport, some 1,500 people, mostly teenage girls with huge crushes on Lonborg, broke through a plate glass door to surround the Sox as they got off the plane.

The Sox were riding high again and manager Dick Williams kept his finger on the top button. In Game Three, 26-year-old rookie Gary Waslewski had been impressive in relief. Williams had been putting his faith in kids all year long, and there was no reason to stop now. Hell, Lonborg was only 25. William skipped over his veterans and started the rookie.

Waslewski teetered and tottered and the stomachs of Boston fans did flip-flops with each pitch, but by the time Waslewski left the game in the sixth inning, the Red Sox led, 4-2. Red Sox hitters had finally woken up – Petrocelli homered in the second inning, then in the fourth, Yaz, Reggie Smith, and Petrocelli – again – all hit home runs. After Brock cracked a two-run home run in the seventh to tie the score, the Sox exploded for four more runs, Gary Bell slammed the door, Boston won 8-4, and the Series was tied at three games apiece.

When a reporter asked Dick Williams who would pitch Game Seven, the manager quipped, “Lonborg and Champagne.” Those words filled the front page of the Boston Herald American the next morning. Confident Sox fans scrambled to the liquor store to stock up, expecting to pop the cork later that day. The elevator was going up again, and the sky was the limit.

But there was one big difference between the Red Sox and Cardinals, one irrefutable fact that no amount of magic or mojo could change. Lonborg, after pitching 275 regular season innings, entered Game Seven on only two days’ rest. Bob Gibson, fresh to begin with, would pitch on his normal three days of rest.

From the start, the Cardinals sensed Lonborg didn’t have it. He escaped the first inning on only nine pitches, but the Cardinals hit him hard. Meanwhile, after walking Joe Foy to start the game, Gibson pitched as if offended.

Lonborg and the Red Sox slowly came down to earth. Dal Maxvill, he of the .279 slugging percentage, tripled leading off the third to start the Cardinals rally, and in the fifth Gibson joined the party with a home run of his own. In the sixth inning, Lonborg hit bottom, and the Cardinals scored three more runs to make the score 7-1. A week earlier, Lonborg had been carried off the field by ecstatic Boston fans. This time, after striking out Flood to end the inning, he walked off the field in tears as Boston fans stood and cheered, knowing the ride was over. Two innings later the Cardinals popped the cork, chanting, “Lonborg and champagne, hey!” as they celebrated their victory.

The Red Sox had been defeated, and the Impossible Dream was over, but somehow that defeat was not a loss. Over the course of a remarkable season the Red Sox had won something more important. After all the ups and downs, in the end, they had won their city back. A year or two before, Red Sox fans could have all shared an elevator with room to spare. Now, the door was bursting and the overflow was packing the stairwell. No one was ever going to get out of the car again until it ended with a world championship. Although they all knew there would surely be more ups and downs, Sox fans were in it for the long haul, convinced that a world championship was now somehow inevitable. They couldn’t wait for 1968.

Now if only Jim Lonborg had not made plans to go skiing …

GLENN STOUT has been series editor of “The Best American Sports Writing” since its inception and is the author and editor of more than eighty books, including “Red Sox Century,” “Yankees Century,” “Nine Months at Ground Zero,” and “The Cubs: The Complete Story of Chicago Cubs Baseball.” He was the winner of the 2012 Seymour Medal for “Fenway 1912: The Birth of a Ballpark, a Championship Season, and Fenway’s Remarkable First Year.” He lives in Vermont.