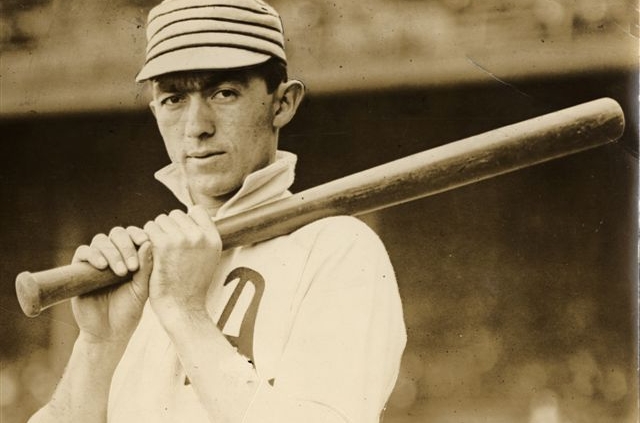

When Did Frank Baker Become “Home Run” Baker?

This article was written by Steven A. King

This article was published in Fall 2013 Baseball Research Journal

The story of how Frank Baker, the Philadelphia Athletics star third baseman, earned the nickname of “Home Run” is well known to even casual fans of baseball. As his Hall of Fame plaque states, he “won two World Series games from [the] Giants in 1911 with home-runs thus getting name ‘Home Run’ Baker.” Baker’s two home runs would understandably gain attention. In the seven World Series beginning in 1903, there had been a combined total of nine home runs hit in 41 games and the highest total in any single series had occurred in 1909 when there were four.1 Only two players, Patsy Dougherty of Boston against Pittsburgh in 1903 and Fred Clarke for Pittsburgh against Detroit in 1909, had hit more than one home run in a twentieth-century series.2

Baker’s home runs would also be important in the outcome of the two games in which they occurred. His first home run, off Rube Marquard in the sixth inning of a 1–1 tie, supplied the two-run margin of victory in the second game of the series. His homer the next day would be even more dramatic, coming off Christy Mathewson in the ninth inning to tie the score at 1–1 in a game the Athletics went on to win 3–2 in 11 innings. Baker might have even added to his home run total in the rest of the Series if not for his being severely spiked in the arm and leg by Fred Snodgrass in the tenth inning of that game. Although Baker did stay in that game and play in the rest of the games in the Series one can only wonder if the injury might have reduced some of his power.3

Although this story of how Baker’s famous nickname came about has become a well accepted piece of baseball lore, it isn’t quite accurate. In fact, Baker was tagged with his famous sobriquet even before he had hit his first regular season major league home run and at least as early as spring training of his rookie year with the Athletics.

On March 28, 1909, an article on the Athletics appeared in the Philadelphia North American describing how Connie Mack was going to split his team, then in spring training, into two squads. One, consisting primarily of rookie players called in the parlance of the time the “Yannigans” or the “Colts,” would be led by Mack on a barnstorming tour and arrive in Philadelphia just before the opening of the regular season. The second team, made up mostly of veteran players and led by team captain Harry Davis, would go to Philadelphia to begin a series of exhibition games against their National League cross-town rivals, the Phillies.

Lest fans feel they would be deprived of seeing any of the Athletics’ new talent, the article noted that the split “does not mean that Philadelphians will not have a chance to see at least some of his [Mack’s] new men in the series. Confident in their ability to make good, Mack assigned [Heinie] Heitmuller, the big California outfielder, “Home-run” Baker, his sensational third sacker, and catcher [Jack] Lapp, who has shown ability, to the veteran combination.”4

What had earned Baker his nickname? The North American article continued, “All of these men have played impressively in the South [the Athletics had trained in New Orleans]. Baker’s work has possibly been the most spectacular. On three occasions he has won close games with home runs, while his fielding inspires the belief that Mack will have the best man at the corner since the days when Lave Cross was good.”

Baker had already displayed his power during his first full season in professional baseball when he played for the Reading Pretzels of the Class B Tri-State League in 1908. According to Baseball-Reference.com, he hit six home runs—leading his team in that category while Charlie Johnson of the Johnstown Johnnies led the league with nine. One player hit eight, three hit seven, and two others besides Baker hit six that season.

Although Baker had failed to homer during his brief initial appearance with the Athletics at the end of the 1908 season, he quickly displayed his power in spring training, hitting a home run in the Athletics’ first practice session in New Orleans on March 11. Heitmuller matched his feat that day but from then on no one on the team, with one exception, came close to Baker with regard to power.

Demonstrating that his practice achievement was no fluke, Baker homered in the Athletics’ first exhibition game on March 17 versus New Orleans of the Southern League. He would do it again on March 23 and March 25 against Mobile. Three home runs during so few games would be an impressive display for any rookie even now but was especially extraordinary in the deadball era. That it wasn’t simply a case of major leaguers taking advantage of minor league pitchers is demonstrated by the fact that through March 28 when Baker was given his nickname, no other Athletics player hit a home run during either of the five exhibition games the team played against minor league teams or the four intrasquad games of regulars versus the “Yannigans” and the one played by former collegians on the team versus those who lacked higher education. For the rest of spring training, only one other member of the Athletics regulars team would hit a home run; on April 4 Topsy Hartsel did so against Newark.

The only other Athletics player besides Baker who demonstrated home run hitting ability was a member of the Yannigan team, a promising young outfielder who would far exceed Baker’s talents as an all around hitter and, while never winning a home run title, become one of the top sluggers in the American League: Joe Jackson. In a game against Louisville on March 29, Jackson hit the ball over the right field fence which also scored a man who would prove to be the second greatest hitter then on the Yannigans, Eddie Collins. The ball Jackson hit was reported to be one of the longest ever recorded in Louisville history, sailing over the right field fence and striking the roof of a street car before landing on a house.5

Baker had no problem staying with the Athletics but his chance to prove that he deserved his recently given nickname was delayed at the beginning of the season. He suffered a knee sprain resulting from a collision at third base with Sherry Magee of the Phillies in an exhibition game on April 7, forcing him to miss the Athletics first five games before making his debut on April 21. However, he quickly made up for lost time, hitting a grand slam in Boston on April 24, the Athletics’ first home run of the season, accounting for all the team’s runs in their victory.6

The next month, Baker would do something even more impressive that would solidify his reputation as a slugger. It had been predicted that due to the vast dimensions of the new Shibe Park it was “improbable that any batsman, even a stalwart hitter like [Ty] Cobb, [Sam] Crawford or [Harry] Davis will be able to drive the ball over the fence.”7 Baker would quickly give lie to this prediction when, on May 29, he hit a ball over the right field wall, the first regular season home run in the history of the park.8 The ball, which traveled an estimated 350 feet before landing on the porch of a house on 20th Street just beyond the right field wall, was described by Connie Mack as the longest and hardest he had ever seen hit.9 For good measure, Baker repeated his feat of hitting a ball out of Shibe Park once again that season on August 9.10

Baker would hit only two more home runs the rest of the season but his total of four was still good enough for sixth place in the American League.11 This tied Harry Davis for second place on the Athletics behind Danny Murphy’s five. Baker’s homer output would fall off the next season to only two before rebounding in 1911 to begin a streak of four straight years when he would lead the league in homers, the second man to accomplish this after Davis.12

And, of course, he did hit those two famous home runs in the 1911 World Series.

STEVEN A. KING is a physician and Clinical Professor at the New York University School of Medicine. He is the editor of the pain management section of “ConsultantLive,” an online journal for physicians, and a member of the board of editors of the journal “Pain Medicine.” The primary focus of his baseball research is New York City baseball at the beginning of the twentieth century and he is writing a book on the interaction between baseball and politics in the city at that time. His most recent baseball articles are on the myth of the Amos Rusie–Christy Mathewson trade that appeared in the Fall 2012 issue of “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game” and on why Rube Waddell missed the 1905 World Series in the 2013 issue of “The National Pastime.”

Notes

1. In comparison, in the seven World Series from 2006 to 2012, there were 76 home runs hit in 36 games.

2. No player would hit more than two home runs in a single World Series until Babe Ruth did it for the Yankees in 1923 against the Giants.

3. Baker would homer again against Marquard in the first game of the 1913 series, his only other World Series home run in the six series in which he played.

4. Unlike Baker, Heitmuller and Lapp would never make a significant impact. Heitmuller would play a total of 95 games for the Athletics in 1909 and 1910 before falling back into the minor leagues and dying at the age of 29 in 1912. Lapp would be back in the minors for part of 1909 before finally sticking with the Athletics for six seasons and the White Sox for one as a back-up catcher. Mack did take with him one player who, having played the full 1908 season with the Athletics, was somewhat out of place with the Yannigans, Eddie Collins. Although Collins’ ability as a major leaguer hitter was already apparent, Mack was unsure if his fielding was at a level for him to be the Athletics regular second baseman and wanted the opportunity to observe him more closely. In contrast, Mack was already certain that Baker would be his third baseman.

5. Philadelphia Inquirer, March 30, 1909; Charlotte Observer, April 1, 1909.

6. According to his biographer, this first home run of his major league career was the only grand slam Baker would ever hit in the majors. Barry Sparks, Frank “Home Run” Baker (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2006), 27.

7. Philadelphia North American, February 22, 1909.

8. David W. Vincent, Home Runs in the Old Ballparks (SABR, Cleveland, 1995), 37.

9. Philadelphia North American, May 30, 1909. Curiously, Connie Mack in a 1946 interview would similarly describe the home run hit by Joe Jackson in Louisville for the Yannigan team as “the longest hit I ever saw in my life.”Jackson’s hit may have grown in Mack’s memory as he recalled it as going over the center field fence instead of the right field fence as reported in contemporary accounts. The New York Times, March 11, 1946.

10. Philadelphia North American, August 10, 1909.

11. Ty Cobb would win the American League home run title in 1909, the only time in his career he would do so. Baker did lead the American League with 19 triples, an impressive five more than the second place finishers, Cobb’s Detroit teammate Sam Crawford and Baker’s teammate Danny Murphy who had been moved to the outfield after losing out to Eddie Collins in the competition to be the Athletics second baseman.

12. Since Baker did it, only Babe Ruth and Ralph Kiner have joined him and Davis in leading their leagues in home runs for four or more straight years. Baker would miss his chance to extend his streak to five straight seasons when he sat out the 1915 season due to a salary dispute with Connie Mack. He did come back to finish second in the league in 1916 after he’d been traded to the Yankees.