When the Angels and Stars Ruled Los Angeles

This article was written by Dick Beverage

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

Long before the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles and the Angels sprang into being three years later, professional baseball and its rivalries had been a central part of the Southern California sports scene. Los Angeles had its first team of professionals in 1890, then joined the fledgling California League in 1892. When this league folded after the 1893 season, Los Angeles was out of Organized Baseball until 1901 when it joined a new version of the California State League. That league evolved into the Pacific Coast League in 1903. The Loo Loos, as the club was first known, won that first pennant in a runaway. In a 211-game schedule they won 133 games and finished 27 1?2 games ahead of second place Sacramento. Los Angeles won pennants in 1905, 1907, and 1908. Clearly, the club was the dominant force in the PCL.

But in a pattern that would repeat itself over the decades, the Angels/Loo Loos were not able to keep the city to themselves. In 1909 a new franchise began play in Vernon, a small industrial enclave located about nine miles from downtown Los Angeles. The Tigers played just a few games within the city limits of Vernon, mostly on Wednesday and the first game of the Sunday doubleheaders. The rest of their home games were played at Washington Park, the home of the Angels. After July 1, 1920 Vernon played all of its home games in Los Angeles.

Vernon remained in the Pacific Coast League through the 1925 season. The club did not draw well in either Vernon or Los Angeles. In 1913 the club moved to Venice, on the Western side of the city, but after two fruitless years there returned to its original site in Vernon. The Tigers were unable to build much of a fan base until 1918, when they finished in first place during a season truncated by World War I. Vernon repeated as champions in 1919 and 1920, but Tigers fortunes declined rapidly after a second place finish in 1922. Meanwhile, the Angels had been purchased by William Wrigley Jr. in August 1921. Wrigley also was the majority stockholder of the Chicago Cubs, and although the two clubs were separate entities, common ownership gave the Angels a definite competitive advantage in Los Angeles. Relations with the Vernon owner, Edward Maier, began to worsen.

When Wrigley purchased land for a new ballpark in south central Los Angeles, he made it clear that the Vernon club could not play its games there. The Tigers would have to find a new home in 1926.

In November 1925 Maier sold the Vernon club to San Francisco interests who immediately announced that the franchise would be moved there. That presented an opportunity to Bill Lane, owner of the Salt Lake City Bees. The Bees had been a member of the PCL since 1915. It had not been a success either on the field or at the box office. Salt Lake had never finished higher than second place and usually hovered around the .500 mark. Attendance had never exceeded 160,000 annually and was generally near the bottom of the league. Even the second place team of 1925, which featured the play of Tony Lazzeri and his 60 home runs, could draw no more than 1,300 per game.

The other PCL owners had complained about the high cost of travel to Salt Lake and the small crowds. Lane moved to take advantage of the open territory in Los Angeles. He and Wrigley had become friends, and the Angels owner offered to share his new ballpark with Lane’s club beginning in 1926. The club played in Los Angeles but took the label of the Hollywood Stars. Informally, it was generally called the Sheiks, after the Hollywood High School athletic teams.

The Sheiks/Stars were expected to be a pennant contender during their first year in Wrigley Field, but they finished in sixth place. The Angels won their first pennant under the Wrigley regime, finishing 101?2games ahead of Oakland. Surprisingly, Angels attendance declined to 273,202 in 1926 while the Hollywood club drew 212,830.

A few years previously the Chicago Cubs had introduced Ladies Day at Cubs Park. Female fans could enter the park at no charge on certain days of the week, and the policy seemed to stimulate attendance. The Angels adopted a similar policy in 1925. But then Mr.Wrigley went one better in 1928—every day was Ladies Day, not only for the Angels games but for Hollywood games as well! The other club owners protested the loss of all that revenue from games played in Los Angeles, and no voice was louder than Bill Lane’s. He revolted against the policy and canceled Ladies Day on June 3. But the Angels continued to open the gates to the women at any time. Finally, Wrigley agreed to pay the other clubs their share of the lost revenue for some games and confine Ladies Day to weekdays only in 1929. But the damage to the friendship with Bill Lane had been done. No longer were the two men on friendly terms, and relations would deteriorate further over the next seven years.

Hollywood fortunes improved in 1928, and for the next four years the club enjoyed its greatest years in Los Angeles. The Sheiks won their first pennant in 1929 when they defeated the Mission club in a season-ending playoff and won again in 1930 when they routed the Angels in the playoffs. There were great players on those two Hollywood champions, most of whom are forgotten today. The best known was pitcher Frank Shellenback, who won 295 games during a Pacific Coast League career that spanned over 19 years. Other important Sheiks were Mickey Heath, Dave Barbee, Otis Brannan, Dudley Lee, John Bassler, and Cleo Carlyle. Except for Bassler, none of these men had significant major league careers, but they contributed greatly to the two pennant winners.

But Hollywood’s fortunes declined after that, and Bill Lane’s team won no more pennants in Wrigley Field. Both the Angels and the Stars were hit hard by the Depression, but Los Angeles fared better, partly because of their relationship with the Cubs, who supplied the Angels with good talent. They won the pennant in 1933 and then overwhelmed the PCL in 1934 with what may have been the greatest minor league team in history. It won both halves of a split season and a total of 137 games. No other Coast League club came close to that mark. Featured players that year were Frank Demaree, the league MVP, pitcher Fay Thomas, who posted a 28–4 record, Jim Oglesby, Jimmy Reese, and Jigger Statz. The success of the Angels that year had a negative impact on attendance throughout the league, and no one was hurt as much as Hollywood. The core of fans that the Stars had developed over the years vanished. By 1935 Hollywood was in last place, and attendance was less than half of what it had been four years earlier. Bill Lane was getting desperate, and when the Angels informed him that his rent would increase to $10,000 in 1936, he decided to move his ballclub. The city of San Diego agreed to build him a new ballpark, and in February 1936 the Hollywood Stars became the San Diego Padres.

But after a two-year hiatus, the Stars would be back. At the end of the 1937 season the Mission club of San Francisco received permission from the league to move to Southern California and would play once again in Wrigley Field in 1938, with the stipulation that it would be for only one year. The second version of the Hollywood Stars would have to find their own ballpark for the 1939 season.

The Stars were sold to a group of Los Angeles investors, fronted by Bob Cobb, owner of the Brown Derby Restaurant chain. Shortly after the sale, Cobb announced the club would have its own ballpark. Gilmore Field, which actually wasin the Hollywood area, was opened in May 1939, and the Stars finally had their own identity. Their move into new quarters created the heated rivalry between the Stars and Angels, who would play each other four series a year in what was frequently called the Heavenly Series.

During the early years of the rivalry, the Angels were especially dominant. They won pennants in 1938, 1943, and 1944 and finished one game out of first place in 1942. During those years the Angels took the season series by wide margins over the Stars in all but one year. Their close relationship with the Chicago Cubs provided them with an abundance of good players, a luxury that Hollywood did not have. The Stars were consistently a second division team in that period. They had no working agreement with a major league club until 1946, when they entered into a limited agreement with Pittsburgh. They finished above .500 for the first time under the Cobb regime and finished ahead of the Angels for the first time.

Los Angeles won the PCL pennant in 1947, but that was the last success the Angels would have for nine years. They slipped to third place in 1948 and then crashed to the cellar in 1949. Conversely, the Stars were beginning the greatest period in their history. They entered into a working agreement with the Dodgers and with the fine players supplied by Brooklyn won their first pennant in 1949 under the leadership of Fred Haney. Chuck Stevens, Jim Baxes, Irv Noren, and Frank Kelleher formed the core of that team, which many Stars fans thought was the best team in their history. Hollywood would win pennants in 1952 and 1953 and have the best record in the PCL during the 1950s. They took control of the Heavenly Series, winning 7 of the last 9 years.

Like Hollywood cowboys who thought the town wasn’t big enough for both of them, the rivalry between these two clubs wasn’t confined to the fans. The players didn’t like each other. There were frequent incidents on the playing field which culminated on August 2, 1953. Fireworks broke out during the first game of a Sunday doubleheader before an overflow crowd. Frank Kelleher was hit by a pitch from Angels hurler Joe Hatten in the sixth inning and charged the mound, wrestling Hatten to the ground. Both benches cleared, punches were thrown, and Kelleher was ejected. Ted Beard was sent in to run for him, and when the next hitter singled to right field, Beard raced all the way to third where he slid into Angels third baseman Murray Franklin with spikes flying. Franklin came up swinging and both benches emptied once again. This was a real fight that inspired Police Chief William Parker, who was watching the game at home on television, to send a brigade of his officers to the park to break up the melee. Several players suffered cuts, bruises, and black eyes. When the fighting subsided, Beard, Franklin, Gene Handley, and Fred Richards were gone, and the reserve players were sent to the clubhouse for the remainder of the day. The donnybrook was featured in the national press, including the popular magazine Life.

Once it became known in late 1957 that the Dodgers were coming to Los Angeles, the Angels and Stars were doomed. The franchises were moved to Spokane and Salt Lake City, respectively, and the great rivalry was over, to be replaced by the Dodgers-Giants rivalry that the Eastern clubs brought with them. But fans of the old Pacific Coast League retain their fond memories of what was really a Heavenly Series.

DICK BEVERAGE is a former President of SABR and a longtime fan of the Pacific Coast League. He is the founder of the Pacific Coast League Historical Society, an organization devoted to preservation of the memories and history of the Pacific Coast League during the years before major league baseball came to the West Coast.

Sources

- Los Angeles Times, 1926–57.

- Los Angeles Examiner, 1926–57.

- Pacific Coast League Record Book, 1956–57.

- Reach Official Baseball Guide, 1903–40.

- Spaulding Official Baseball Guide, 1925–40.

- Spaulding-Reach Official Baseball Guide, 1941.

- Sporting Life, 1903–15.

- The Sporting News, 1903–57.

- The Sporting News Baseball Guide and Record Book, 1942–43.

- The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide, 1944 –58.

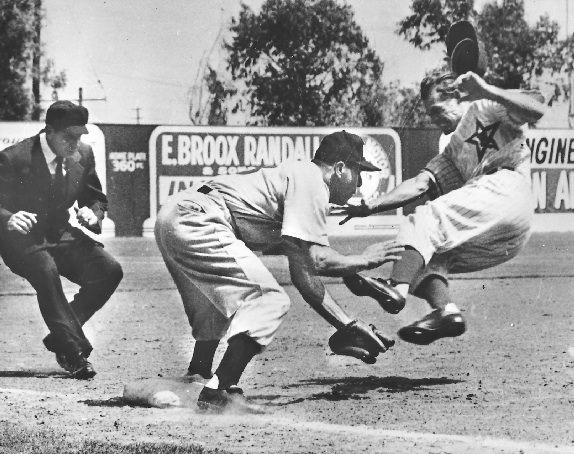

1. The trigger for the biggest brawl in PCL history. Hollywood Stars outfielder Ted Beard slides spikes-high into Los Angeles Angels third baseman Murray Franklin, August 2, 1953.

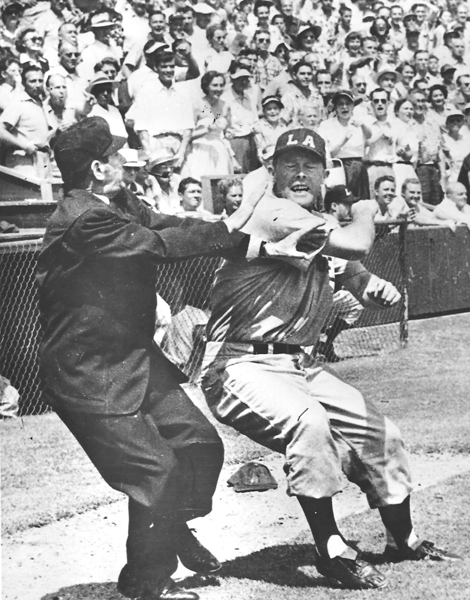

2. Seconds later, Beard comes up swinging.

3. The brawl spreads as Angels catcher Al Evans winds up for a swing at umpire Joe Iacovetti.

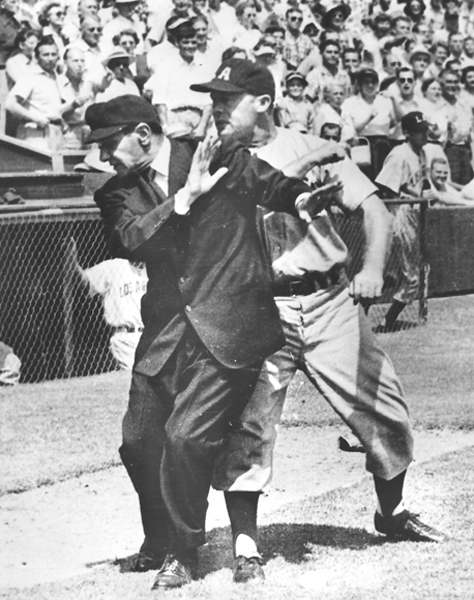

4. Fortunately for Evans, his punch misses.

5. Evans moves to crowd Iacovetti.

(All photos provided by David Eskenazi.)