Which Manager Knew First That the 1919 World Series Was Fixed?

This article was written by Tim Newman

This article was published in The National Pastime: Heart of the Midwest (2023)

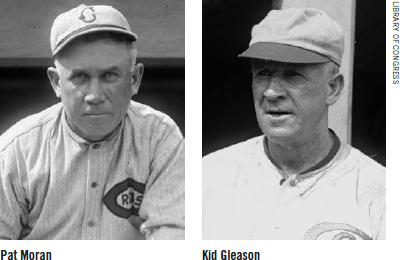

Several players on the 1919 Chicago White Sox agreed to lose that year’s World Series, earning the nickname “Black Sox.” Their manager William (“Kid”) Gleason said publicly after the Series that “something was wrong. I didn’t like the betting odds. I wish no one had ever bet a dollar on the team.”1 Gleason had good reason to know that his team had been fixed. White Sox owner Charles Comiskey passed along a tip to that effect on the morning before the second game. The tip came from well known gambler Mont Tennes, whom Comiskey apparently deemed credible.2

Gleason probably knew more, earlier, and from a source that he trusted.

BILL BURNS WAS CLOSE FRIENDS WITH BILLY MAHARG

The players first discussed the fix during a train ride one month before the Series.3 At their hotel in New York City in mid-September, Black Sox Eddie Cicotte and Arnold Gandil sought money from a former major leaguer and outwardly prosperous acquaintance selling oil leases named Bill Burns. Unbeknownst to the players, Burns could not meet their financial demand, so he summoned his friend Billy Maharg from Philadelphia.4

Maharg was born in Philadelphia, and had left school when he was 10 to work on a farm. At age 38 in 1919, Maharg worked for the Baldwin Locomotive Company as a driller.5,6 He enjoyed some local celebrity as a former boxer.7

In 1920, Maharg famously told the story of his involvement in the fix to legendary Philadelphia sportswriter James Isaminger. Maharg related how Burns wired him to come to New York City, and when he got there Burns was planning a hunting trip with White Sox pitcher Bill James.8 Maharg had spent time hunting with Burns in Texas several years earlier.9

Burns had a long history of hunting big game with big leaguers. In 1910, he gathered a hunting party that included future Hall of Famer Tris Speaker.10 During the 1911 season several players, including Phillie Tub Spencer, said that they would spend the winter on Burns’ ranch in San Saba, Texas.11 That October, Phils rookie sensation and future Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland Alexander said that he would also go to Burns’ ranch to spend a part of the winter.12

In 1916 Burns and his pack of bloodhounds met James in New Mexico to hunt bears and mountain lions.13 Bill Rodgers, who spent most of 1916 in the Pacific Coast League and accompanied Burns and James on the 1916-17 trip, said that “Burns is a bug on dogs.14 Some of his seven pups were good bear dogs.” Maharg raised hunting dogs.15 During a drive from Santa Rita, New Mexico, where the Chicago Cubs had lost to Burns’ team of copper miners in a 1918 spring training game, Alexander and Burns shot crows and quail from their car.16

Just before his trip to New York City in 1919, Burns had visited Philadelphia, where he had some success selling oil leases. Around September 9 he sold an oil lease to Harry C. Giroux.17 While neither Burns nor Maharg ever mentioned meeting the other in Philadelphia, Maharg’s connection is beyond coincidental. Maharg was an accomplished dancer who found time to teach at the renowned Wagner Ballroom in Philadelphia.18 Giroux worked at the Wagner Ballroom from 1918 until retiring as the manager in 1962.19

Burns saw Cicotte and other Chicago players while he was in Philadelphia.20 Third-string White Sox catcher Joe Jenkins said later that blue laws in Philadelphia prohibited baseball on Sundays, so he played in a high-stakes craps game with Burns at the hotel.21 The date was probably September 14, 1919, when the White Sox had a Sunday off.

After the World Series, Maharg bought two oil leases from Burns. On both, Maharg was part of a group that included Giroux and Charles Gey.22 Gey led the Jazzy Jazz orchestra that played the Wagner.23,24

MAHARG WAS CLOSE FRIENDS WITH GROVER CLEVELAND ALEXANDER, BILL KILLEFER, AND PAT MORAN

Maharg might have been the only person whom Burns both trusted and thought might have the connections necessary to raise the money. Maharg met Burns in 1908 or 1909 when the latter broke in to the major leagues with Washington.25 They probably came to know each other better when Burns was acquired by the Phillies in May 1911, where Burns joined a pitching staff headed by Alexander. Alexander lived with Maharg when he was a member of the Phils, and they remained lifelong friends.26,27

Three months after Burns joined Philadelphia, the Phillies purchased the contract of catcher Bill Killefer. Killefer and Alexander immediately meshed and were best friends off the field.28 According to Isaminger, “From attending ball games at the Phillies’ park [Maharg] became very friendly with Alexander and Killefer. … Alexander had an automobile and Maharg drove it for him. The pitcher and catcher and Maharg were inseparable, and while Maharg’s duty was to drive the car he was always ‘one of the party.’”29 It probably helped that Maharg was or had been an auto mechanic.30

By 1915 Burns was out of the major leagues, but Pat Moran—the backup catcher from that 1911 Phillies team—had been hired to manage the Phillies. During spring training Moran introduced the concept of catchers using combination signs to signal the pitcher, thus thwarting opposing baserunners from tipping the upcoming pitch to the batter.31 Alexander won 31 games in 1915, and Killefer was the regular catcher.

Maharg was still around too—helping Moran steal the signals of teams visiting the Baker Bowl:

[I]n the spring of [1915] the Phillies suddenly changed their players’ bench to the first base side of the field, the visiting teams occupying the bench at the third base side, which had always been used by the home team.

When they changed players’ benches they had a small door at the back of their old bench which was now to be used by the visiting team closed up so that it was impossible to get from the players’ bench under the stand without going around by way of the bleacher entrance.

Behind this wall, under the grandstand, a hole was dug in the soft ground, and Maharg was used as a spy to hide in this hole with his ear to the cracks of the nailed-up door so he could hear the conversation of the visiting players and catch their signals and plays. He would then report this information to Manager Moran by returning under the grandstand to the Phillies’ bench, the door to which had not been closed, with the result that the Phillies usually knew every play their opponents were about to pull in advance.32

The Phillies won the National League pennant in 1915, a substantial improvement over their sixth place finish of the previous year. But they refused an offer to stage the coming World Series games at the more spacious Shibe Park several blocks away.33 The Phils won the first World Series game at home, but then lost the next four and the Series.

Moran insisted that Maharg travel with the Phillies on occasion, and Maharg was identified in 1916 as the Phillies assistant trainer in their team photo.34,35 Moran put him into that year’s final regular season game. A Pennsylvania paper reported, “Butterball Maharg, the king of the chauffeurs, went to right in the ninth.”36 The New York Times called it “a travesty on the national game.”37

KILLEFER WAS TIGHT WITH OTTO KNABE, WHO WARNED HIS LONGTIME FRIEND AND BUSINESS PARTNER KID GLEASON

After the 1917 season, the Phillies traded Alexander and Killefer to the Chicago Cubs. The move shocked the baseball world.38 The trade did reunite Killefer with Cubs coach Otto Knabe, who had been the Phillies second baseman from the time it was ceded to him by his mentor Kid Gleason in 1907, until 1913.

The Phillies let Moran go as their manager when his contract expired following the 1918 season. That did not stop Moran from betting $500 on that year’s World Series.39 It is not known whether he bet for or against Killefer and the Cubs (who lost to the Boston Red Sox). For the 1919 season Moran was hired to manage the Cincinnati Reds, and Gleason was hired to manage the White Sox.

The train that pulled out of Chicago at 5:00 PM on August 11, 1919, carried Burns, Alexander, Killefer and Knabe.40 It may have been during this trip that Burns convinced Cubs Fred Merkle and Speed Martin, and manager Fred Mitchell, to buy an oil lease that Killefer held in trust.41 Knabe left the Cubs for the year when the train got to Syracuse, to attend the famous horse races in Saratoga.42 There is no telling whether Knabe saw alleged fix financier Arnold Rothstein win $200,000.43

After Saratoga at the end of August, Knabe headed back to Philadelphia to look after the business that he owned with Gleason. Knabe let it be known that he would share with Gleason any insights he had on Chicago’s World Series opponent, Moran’s Reds. Knabe also intended to bet on the Series.44

The business that Knabe and Gleason owned was variously described as a billiard hall and/or a bowling alley.45,46 Knabe was indicted in 1938 for running a gambling house and “pool selling” in Philadelphia. The Philadelphia Inquirer said that Knabe had operated the place for many years.47 At trial, the police described the operation as a sumptuous casino with former light-heavyweight boxing champion “Battling” Levinsky at the peephole.48

Whether or not they were the same business, sportswriter Effie Welsh said that the former one also made book. Welsh also said that Knabe had a pool of money he was prepared to bet on the White Sox to win the 1919 World Series when a ballplayer friend told him that the Sox had been fixed. Knabe corroborated the tip, and then informed Gleason. They quarrelled and the longtime partners split up.49

This scenario is perfectly plausible. White Sox executive Harry Grabiner identified the player who warned Knabe as none other than Bill Killefer.50 The Cubs ended the 1919 season in Cincinnati, and Killefer stayed in town for Game One of the Series. Knabe was at Game One, so there was ample opportunity for him to have talked to Killefer.51 Gleason arrived in Cincinnati with the White Sox on the day before the first game, so there was ample opportunity for him to have heard about the fix from his longtime friend Knabe before the Series started.

BUT IF KILLEFER TOLD KNABE, THEN HE PROBABLY TOLD MORAN, TOO

Would Killefer have told Knabe that the fix was in, but not Moran?

Killefer joined the parade after the Reds’ clinched the National League pennant, and Moran asked Alexander and him to share their wisdom with the Reds’ players before the Series started.52, 53 Presumably Alexander and Killefer were still around while their wives spent Game One in a box with Moran’s wife.54 Alexander and Killefer are also known to have visited the Reds’ clubhouse after the fifth game in Chicago.55

Thus it seems likely that if Killefer told Knabe about the fix, then he probably told his old friend Moran as well.

But Moran never said when he learned of the fix, and Gleason never acknowledged getting any tips earlier than the morning of Game Two. The closest he came was in a column he wrote on the day that the Series ended. “I wasn’t in the betting, but I know that a host of my friends in Philadelphia were backing my team. … There never were so many rumors of crookedness floating around, as have been in the air since Labor day. One story had it that seven players on my ball club were on the Cincinnati end of it and had gobbled up some enticing odds in the series wagering.”56 Gleason told the grand jury investigating the fix that he had no definitive proof, only suspicions about his team’s play, particularly in 1920.57

Moreover, Maharg was probably not the source of Killefer’s information. They were clearly close friends, but at all relevant times Maharg was in Philadelphia while Killefer was with the Cubs in the West. Maharg also claimed to have kept quiet until he publicly exposed the scandal in 1920: “My closest friend is Grover Cleveland Alexander, and when he was here [in Philadelphia] with the Cubs this year [1920] I never said a word to him about it.”58 Alexander immediately acknowledged that “Maharg always impressed me as being truthful and honest.”59

Maharg could have wired or phoned Killefer. But it is more probable that Burns told someone, maybe his old hunting buddy Bill James. In addition to the multiple instances already mentioned, Burns and James repeated their hunting trip in the winter of 1918-19.60 On that day in September 1919 at the Ansonia Hotel when Cicotte and Gandil first broached the idea of the fix, Burns and James were planning another trip for that winter. But Burns said that the trip was postponed and then canceled, and that James never knew anything about the fix.

Finally, Knabe was a constant caller at Gleason’s bedside while he was dying in 1933.61 He also served as an honorary pall bearer (with Killefer) at his funeral.62 Were Knabe’s actions those of an estranged protege, or was there never any need to do that?

So who knew about the fix first, Gleason or Moran? You decide.

TIM NEWMAN is a patent attorney in Austin, Texas. He has been a member of SABR since 2000.

Notes

1. Chicago Tribune, October 10, 1919, 19.

2. Deposition of Charles Comiskey taken March 24, 1923, pertaining to civil lawsuits filed by Oscar Felsch, Joe Jackson, and Swede Risberg against the White Sox. These records are in private possession, but are abstracted in Gene Carney, “New Light on an Old Scandal,” Baseball Research Journal (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2006) Volume 35, 74. Some details are missing from Carney’s summary. The various reports of what Kid did with his information are ably summarized in Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2006) 46-47.

3. William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2013) 50; and sources cited therein.

4. Timothy Newman, “Why the Black Sox Almost Got Away With It,” The Inside Game, SABR Deadball Era Committee, February 2023.

5. Maharg’s testimony in the criminal trial of the Black Sox recounted in the New York Herald, July 28, 1921, 9.

6. Maharg’s World War I draft registration card, dated September 1918.

7. See Bill Lamb’s outstanding biography of Maharg at SABR BioProject: https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/billy-maharg.

8. James Isaminger, “My Part in ’19 Fix-Maharg,” Philadelphia North American, September 28, 1920 (reprinted in Baseball Digest, October-November 1959, 9).

9. Burns’ testimony from the criminal trial appears, for example, in the Philadelphia Inquirer, July 20, 1921, 1.

10. Arizona Republican, September 2, 1910, 7; Ft. Worth Star-Telegram, November 11, 1910.

11. Sporting Life, August 26, 1911, 7; Gandil played semipro ball with Spencer in 1920. Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1920.

12. Harrisburg (PA) Patriot, October 17, 1911, 8. Maharg may have joined this trip. Maharg testified they did not see each other for several years after Burns left the major leagues in 1912. Deposition of William Maharg, taken December 16, 1922 (note 2).

13. Western Liberal (Lordsburg, NM), November 3, 1916, 1; Oregonian, February 22, 1917 (this report has Burns’ dogs as Airedales). James at that time was playing for Detroit. James also collected a controversial payment from Gandil and White Sox shortstop Swede Risberg in 1917. James’ biography is at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bill-james-2.

14. Oregonian, February 22, 1917.

15. At least later in life. Jerry Jonas, “He helped ‘fix’ the 1919 World Series,” Daily Intelligencer (Doylestown, PA), October 11, 2009, 34.

16. Oscar C. Reichow, “Alex Expected to be a Sniper,” Chicago Daily News, February 13, 1919, 2.

17. Assignments dated September 9, 1919, recorded in San Saba County, Texas.

19. Giroux’s obituary is in the Philadelphia Inquirer, November 10, 1969, 10.

20. Deposition of William Burns taken October 5, 1922 (See note 2).

21. “Hanford’s Jenkins, Black Sox Innocent, Talks of One Big Smirch on Baseball,” Fresno (CA) Bee, May 13, 1962, 26. Jenkins also said that Abe Attell was there, which is harder to believe, but Burns was known to play poker and shoot craps. First tip of the cap to the late Gene Carney for his Notes, #388 discussing the deposition of Chicago sportswriter Hugh Fullerton.

22. Assignment dated October 20, 1919, recorded in San Saba County, Texas.

23. Reading (PA) Times, July 9, 1918, 5.

24. https://www.city-data.com/forum/philadelphia/1924588-whatever- happened-wagners-ballroom-3.html (accessed December 15, 2022). Another lease, to Hall of Famer Max Carey and several of his Pittsburgh Pirates teammates, was recorded on the same day. This suggests that the dates that the Assignments were recorded are not necessarily the dates that they were signed.

25. Deposition of William Maharg (note 12).

26. “My Part in ’19 Fix-Maharg” (note 8) 13. It is unclear how much Maharg lived at the Hay Market Hotel. He may actually have lived at 1819 N. Park, at least in 1918 (the address he listed on his draft registration card) and 1919 (per the address on the telegram shown in this article).

27. Alexander’s wife said in 1951 that her husband’s “friend” Maharg had called her in 1929 about Alex’s health. Sporting News, May 2, 1951, 14.

28. Killefer caught Alex on October 3, the first of 250 times they would be the starting battery in big league games. The SABR biography of Bill Killefer by Charlie Weatherby is at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bill-killefer.

29. Pittsburgh Press, July 24, 1921, 20; The author was unable to find this article in any other newspaper.

30. At the Hay Market Hotel (note 26). Maharg deposition (note 12).

31. Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Story Behind the Innovations that Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010) 236.

32. Jim Nasium, “Maharg Was Used by Moran as a Spy,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 1920. Jim Nasium was the pen name of Edgar Forrest Wolfe.

33. The 1915 Philadelphia Phillies: National League Champions, https://www.philadelphiaathletics.org/history/the-1915-philadelphia-phillies-national-league-champions (accessed December 16, 2022).

34. Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 1920, 18 (note 32); Pittsburgh Press, July 24, 1921, 20 (note 29).

35. Deadball Stars of the National League (SABR, 2004) 185. Maharg is seen in the photo that was apparently taken very late in the 1916 season, standing on the far left, distinctive in suit and tie; Lamb’s biography of Maharg says that the photo can also be found in Paul G. Zinn and John G. Zinn, The Major League Pennant Races of 1916 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2009).

36. Lancaster (PA) Daily New Era, October 6, 1916, 8.

37. Lamb’s biography of Maharg, note 17, citing The New York Times, October 6, 1916.

38. White Sox executive Harry Grabiner suggested that Alex and Killefer were traded by former NYC police commissioner William Baker “after they were crooked.” William Veeck with Ed Linn, The Hustler’s Handbook (Baseball America Classic Books, 1996) 226.

39. Sean Deveney, The Original Curse (McGraw Hill, 2010) 57; Gleason also bet on baseball at least once on a Labor Day 1917 game with the Tigers that Gandil and Swede Risberg alleged was fixed. Rick Huhn, Eddie Collins: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2008) 188, citing Collins’ letter to Commissioner Landis dated February 24, 1921, in the Black Sox Scandal files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York.

40. Chicago News, August 11, 1919.

41. Assignment dated August 30, 1919, recorded in San Saba County Texas.

42. Pittsburgh Press, August 16, 1919; Chicago Tribune, August 13, 1919, 15, has Knabe proceeding to NYC with Alexander, Killefer, Claude Hendrix, and Jim Vaughn.

43. Collyers Eye, August 16, 1919, 4; Cubs owner Charles Weeghman claimed this is where Tennes tipped him that the upcoming World Series was fixed.

44. Philadelphia inquirer, August 31, 1919. Before the 1919 season, Gleason and Knabe attended a boxing match together. Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, March 11, 1919.

45. The Sporting News, January 16, 1919, 8, discussing Gleason’s appointment as manager of the White Sox. Gleason left his team at least once during the 1919 season to go to Philadelphia. “Sox to Battle Senators Today in Hot Capital,” Chicago Tribune, September 9, 1919, 17.

46. See for example Binghamton (NY) Press and Sun-Bulletin, August 28, 1919, 14.

48. Philadelphia Inquirer, November 9, 1939, 19.

49. Statement of Effie Welsh, sportswriter for the Wilkes-Barre (PA) Times Leader, dated September 28, 1920, printed in the Boston Globe the next day (another shoutout to Gene) and in the New York Sun and Herald, 13. Welsh may have known Buck Weaver growing up. Weaver barnstormed with Babe Ruth to California, where they golfed with Bill James, Kerry Keene, Raymond Sinibaldi, David Hickey, The Babe in Red Stockings: An in Depth Chronicle of Babe Ruth with the Boston Red Sox 1914-1918 (Sagamore, 1997) 282.

50. Veeck (note 38) 225; From the context of Veeck’s discussion, the information may have come from detectives hired to investigate the fix rumors.

51. Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia), October 1, 1919, 15.

52. As noted by Cubs’ beat writer Charles Dryden’s column dated September 27 in the Richmond (VA) Times-Dispatch September 28, 1919, 21.

53. Before they all left to attend the horse races across the river at Latonia. San Francisco Examiner, September 30, 1919 18.

54. Susan Dellinger, Red Legs and Black Sox (Emmis Books, 2006) 207, note 9, citing the Cincinnati Enquirer, September [sic: October?] 2, 1919. To be fair, Christy Mathewson wrote that Knabe served on Moran’s “strategy board.” Detroit Free Press, October 6, 1919, 12.

55. Cincinnati Post, October 1, 1919. For good measure Alexander also visited the headquarters of the White Sox boosters, known as the Woodland Bards, after Game Two. Cincinnati Post October 1, 1919.

56. See for example Pittsburgh Press October 10, 1919, 40. Taken with the quote from note 1, Gleason seemed to have more sympathy for the people who lost money than anger at the fixers or his guilty players.

57. Lamb (note 3) 70-71, note 38 and sources cited therein.

58. Philadelphia North American, September 28, 1920 (note 8).

59. See for example Brooklyn Daily Times, September 28, 1920, 1.

60. Los Angeles Herald, September 2, 1919, 15.