Why did Wrigley, Lasker, and the Chicago Cubs Join a Presidential Campaign?

This article was written by Mark Souder

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

While professional baseball and politics have always been linked, only once has a major league baseball team become a voluntary part of a Presidential campaign.

The visible evidence of this happenstance is the 1920 Chicago Cubs’ exhibition game in a small Ohio town against a squad of local semi-professionals called the Kerrigan Tailors.

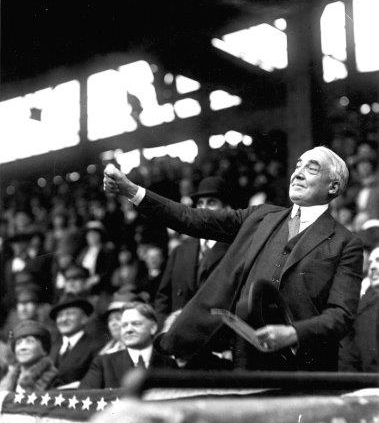

United States Senator Warren Harding, the Republican candidate for President, was running a controlled “front porch” campaign in his hometown of Marion, Ohio. Two Chicago men—the original advertising “Mad Man,” Albert Lasker, and the King of Gum, William Wrigley Jr.—were behind not only the game but also the election of Warren Harding as President. How and why did this happen?

Why Did the Harding Campaign Need Baseball?

Things were going well for the Harding campaign in 1920, due in large part to the first comprehensive presidential “marketing campaign” to include national advertising. Unfortunately, however, Warren Harding liked to play golf. Not that golf is bad, but during the “Progressive Era” of American politics, it was perceived as somewhat less than manly, a game played only by the rich. During this time in America, the wealthy were not universally adored.

Things were going well for the Harding campaign in 1920, due in large part to the first comprehensive presidential “marketing campaign” to include national advertising. Unfortunately, however, Warren Harding liked to play golf. Not that golf is bad, but during the “Progressive Era” of American politics, it was perceived as somewhat less than manly, a game played only by the rich. During this time in America, the wealthy were not universally adored.

Democrat Woodrow Wilson had won the previous two Presidential elections because of divisions between “progressive” and “stand pat” Republicans. An Indiana politician, Will Hays, had worked to bring peace to the party’s warring factions. Will Irwin, founder of Cummins Engine in Columbus, Indiana, held Indiana’s second-ranking political post. He recommended that Hays contact a business colleague—an advertising genius from Chicago named Albert Lasker. 1

Lasker’s brilliance in advertising had led to repeated business success. California oranges were rotting and going unpurchased until Lasker branded them “Sunkist.” Raisins weren’t doing well; prunes were, in fact, more popular. (This period saw multiple California baseball teams called the Prunes, but no California Raisins.) Lasker rescued the sun-shriveled grapes by naming them “Sun-Maid.” 2, 3

The Kimberly-Clark Corporation was stuck with excess paper products after World War I. Soon, their “Kleenex” product would become a generic term, Lasker having added “makeup remover” to the box to encourage women’s purchases. The same company was unsuccessful in selling sanitary napkins until Lasker’s advertising campaigns and improved product placement—heretofore it had to be bought from male druggists—made Kotex seem essential. As part of the deal for promoting Kimberly-Clark, and his other clients, Lasker received company stock as payment, so he did extremely well for himself. His home outside Chicago included 450 acres and 55 servants.

Lasker and his cadre of top-flight marketers and copywriters did it all: branding, advertising, sales strategy, and the like. Only the phenomenally successful Lucky Strike cigarette campaign was a joint effort with the company itself.

Will Hays, by this time National Republican Chairman, asked Lasker to meet with Harding and translate business marketing to politics. Lasker brought along a friend, William Wrigley, Jr.

Like Lasker, Wrigley was a great marketer. He certainly knew how to sell gum, and like Lasker, had the most valuable commodity in politics: money. Lots of it. With Wrigley on board, Lasker agreed to run Harding’s advertising and marketing.

Interestingly, Will Hays became—after just one year in Washington—the nation’s film czar, tasked with restoring public confidence in a new and powerful industry in danger of being sunk by the bad publicity resulting from pornographic movies (and criticism of the mostly Jewish film producers). At the same time Kenesaw Mountain Landis was trying to clean up baseball, Hays instituted a moral code governing what films “should” and “shouldn’t” legally show until the 1960s. While this code was said to be voluntary, it had its intended effect. 4

Albert Lasker was not only a wealthy advertising genius pioneering political marketing and advertising; along with his friend William Wrigley, he also owned the Chicago Cubs. To Lasker and Wrigley, the Cubs were mostly a hobby, rather than a source of their wealth. Baseball was a game: politics was about how nations would be ordered. And since the major issue of this presidential campaign was the League of Nations, this campaign was about the future of the world.

Unfortunately, someone associated with Harding thought a newsreel of the president playing golf would help his image. This was a serious issue, because newsreels were the only form of video communication available in 1920. And once people began seeing the newsreels in July, “Harding playing golf” bombed. 5

While the resulting flood of negative mail against golf and those who played it is interesting, perhaps more interesting is this: in 1920, Lasker was already pioneering immediate market research. “Exit polling” was not invented by modern political consultants or television networks. At selected theaters, note-takers were on hand to hear comments from exiting viewers. Feedback quickly identified that the “golfing” portion was a disaster—Harding was identified as “rich,” not a common man.

It didn’t take long for the data to confirm that Harding was in trouble. One can only imagine the yelling, blame-throwing, and semi-panic at Republican headquarters in New York and Lasker’s ad agency in Chicago. “Now,” I’m sure the campaign and advertising planners were saying, “some idiot is about to undo everything we’ve done by associating Harding with golf.”

Every campaign has at least one pivotal moment. This was one. How could the campaign, with the election three months away, pull Harding out of this pit? Obviously, the League of Nations, the stormy rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia, and post-war labor turmoil in the US were the real issues of the campaign, but to be heard on those issues, Harding needed to be a man of the people not an effete rich guy.

The answer? Associate President Warren G. Harding with a manly, American common sport—baseball! Call Wrigley up and let’s get those Chicago Cubs over to Marion now .

The Cubs had a break in their schedule just before Labor Day. Lasker started seeking an opponent. No other team in the region had an off day, but double-headers were common so schedules could be adjusted. In political terms, scheduling was a “fake” problem; the problem was real but could be fixed if one wanted to fix it. Lasker, however, immediately ran into political problems—some in “real” politics and some in baseball.

Harding was a fan of the Cincinnati Reds. (One could literally say Harding was a die-hard fan, since his last discussion before dying was to ask his wife how the Reds had done that day.) But Cincinnati itself presented a variety of problems.

Garry Herrmann was the President of the Reds and head of the National Commission, the three-man governing body of baseball. The Reds had also won the 1919 World Series against the “Black Sox.” Sportswriter Hugh Fullerton, in 1920 employed by the Harding campaign, had warned the year before of a rumored Series fix. Lasker and Wrigley were already furious at Herrmann for trading the Cubs a ballplayer whom Herrmann knew had tried to fix a game. Frustrated with the potential ruin to the integrity of the game, Lasker proposed a plan for reorganizing baseball. 6

Real politics was involved as well. Cincinnati had been run politically for decades by the most famous political boss west of Tammany Hall: George Cox. Herrmann and a fellow Cox sidekick managed patronage. They were part of the Ohio Republican Party’s anti-Taft, anti-Harding, pro-Senator Joseph Foraker faction. To them “progressive” was a curse word. The most successful politician in their web was Mayor Julius Fleischmann, a wealthy man due to his family’s whiskey and yeast connections (their most famous product came later). Lasker’s request to the Reds came through the Jewish financial sources behind the 1920 Reds, but Herrmann made it clear that the Reds would not adjust their schedule to accommodate Warren Harding, of all people. So the Reds were out. 7

Most baseball sources suggest that Lasker then pursued an agreement with Charles Stoneham, the owner of the New York Giants. Unfortunately, John McGraw kiboshed the deal for political reasons. The problem with this theory is that Stoneham was aligned with Tammany Hall. While Tammany was no fan of Democrat Vice-Presidential nominee Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) in 1920, it is unlikely that Stoneham wanted to help Lasker promote Harding. There was also the matter of Stoneham’s close ties to gambling kingpin Arnold Rothstein, who was already being fingered as the man behind the 1919 Series. It seems implausible that the New York Giants would help to rescue Harding’s image. 8

Then there was nearby Cleveland, home of the American League Indians, a contending club that later that year won one of its two World Series championships. The Indians were highly unlikely to change their schedule. There was also a serious baseball politics problem. New Indians owner Jim Dunn had purchased the team with a $100,000 loan from AL president Ban Johnson, a loan on which he still owed $60,000. The premise of the Lasker baseball re-organization plan was that someone not under control of the owners should make decisions so the public would have more “confidence” in those rulings. Johnson, along with Herrmann a fellow “target” of plan, would not rescue Lasker’s guy until Hell, not Lake Erie, froze over. 9

The solution was to simply tap into the huge local network of baseball teams. Every town back then had semi-pro clubs sponsored by local companies, often with former college, high school, or minor league players in their ranks. And that is how the Kerrigan Tailors came to play the Cubs on September 2, 1920.

Warren Harding even briefly pitched in the game, and the Cubs loaned Kerrigan a pitcher as well. The outcome of the game only mattered to the folks watching that day. The true purpose of the event was to generate moving pictures of Harding playing and talking baseball with famed pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander and the other Cubs. Once shot, these films were sent to the nation’s theaters. As we politicians say, “great video.” The golf issue was buried.

Wrigley and Lasker: The Friendship

Lasker and Wrigley’s partnership as owners of the Cubs is well documented. Whether they were friends is speculative at best. Lasker had nominated Wrigley as a Cubs director before actually meeting him. Lasker’s hideaway office was in the same building as Wrigley’s, so after nominating him, Lasker convinced Wrigley to accept the post. As the team’s largest shareholder, Lasker had demanded that Wrigley be on the board because he wanted some allies with cash and business sense.

Lasker and Wrigley’s partnership as owners of the Cubs is well documented. Whether they were friends is speculative at best. Lasker had nominated Wrigley as a Cubs director before actually meeting him. Lasker’s hideaway office was in the same building as Wrigley’s, so after nominating him, Lasker convinced Wrigley to accept the post. As the team’s largest shareholder, Lasker had demanded that Wrigley be on the board because he wanted some allies with cash and business sense.

Wrigley never utilized Lasker’s advertising agency. This would make most investigators a tad suspicious about the closeness their relationship, especially since soon after Harding’s victory, Wrigley bought out most of Lasker’s Cubs shares. The newspaper stories of the time have a variety of excuses, as do biographers, but only one makes sense: both had strong opinions and wanted to stay friends, so one backed down. To say that neither was good at being a follower is to understate the point. 10 , 11

Lasker and Wrigley continued to serve on the board of Chicago’s Foreman Bank after dissolving their Cubs partnership. The son of the bank’s founder had married Lasker’s daughter. Lasker, however, seemed to avoid advertising entanglements with his friends. (They may be the only people he didn’t hard-sell.) A close friend of Lasker founded the Yellow Cab Company in 1915 and went on to considerable business success. John D. Hertz and Lasker were such good friends that they shared a bank account to which either could make changes without the other’s knowledge. Just prior to the stock market crash of 1929, Hertz withdrew and sold the account’s stocks, including Lasker’s.

While Lasker was initially upset at what Hertz had done—he did not agree that the market was going to crash—the action saved Lasker’s fortune. But like with Wrigley, Lasker never handled the advertising for Yellow Cab or other Hertz corporation properties.

While they seemed to be friends and shared some interests, there is no evidence that Wrigley and Lasker were personally close. In 1911, Wrigley purchased a mansion near Lincoln Park and a summer home on Lake Geneva, but after the gum company went public in 1919, Wrigley increasingly spent time (and money) out West. Lasker moved to Washington in 1921 after Harding won, not returning to Chicago until after Harding’s death.

Lasker appears not to have viewed Wrigley as an intellectual equal. While Wrigley seemed to be a friend of everyone and certainly did not shy away from being linked with Lasker, it is safe to assume that Lasker’s Jewish activism led him to different social circles than Wrigley’s. 12

Personalities are also important to friendships. Lasker was intense about everything: Wrigley was intense about gum. Fortune magazine once likened Wrigley to a jolly bartender. No one said that about Lasker. Wrigley seemed to be the eternal optimist. Lasker veered between optimism and a sometimes debilitating depression. They appeared to respect each other and get along when necessary, but “close” would not describe their friendship. In politics, “my good friend” means you aren’t enemies. 13 14

Wrigley and Lasker: The Politicians

While the Cubs were a valuable political prop at a critical moment in Harding’s campaign, it does not explain why Lasker and Wrigley agreed to meet with Harding at his Ohio home long before the Cubs were needed. Both men had actively supported major alternatives to Harding at the Convention. The core question, of course, is why wealthy businessmen become involved in politics, and the numerous answers vary in emphasis by individual.

While the Cubs were a valuable political prop at a critical moment in Harding’s campaign, it does not explain why Lasker and Wrigley agreed to meet with Harding at his Ohio home long before the Cubs were needed. Both men had actively supported major alternatives to Harding at the Convention. The core question, of course, is why wealthy businessmen become involved in politics, and the numerous answers vary in emphasis by individual.

The issues dealt with by government, especially the Federal Government, have always been sweeping. In that time, “trust” (monopoly) rulings could make or break a business. Lasker and Wrigley were both part of the “progressive” movement. Business owners, especially Protestant and Jewish, tended to associate with reformers fed up with big-city political corruption. Chicago has a deserved historic reputation for corruption.

Lasker initially supported California Senator Hiram Johnson—Teddy Roosevelt’s Vice-Presidential partner for the Progressive Party in 1912—in his bid for President. Lasker is said to have drawn Wrigley into both baseball and the Johnson campaign.

This claim, however, is simplistic. Lasker claimed that Wrigley knew nothing about baseball, though Wrigley had sponsored a semi-pro team years earlier called the Wrigley Nips. He also appears to have played the game growing up in Philadelphia. And Wrigley was an avid admirer of Teddy Roosevelt, so converting him to a campaign for Hiram Johnson would not have been especially difficult. TR, who had hoped to run in 1920, died in 1919, and Johnson was his political heir.

Johnson was not especially likable and was busy proving that he had no chance to win. Reformers began to cluster around General Leonard Wood as a candidate. Wrigley and Lasker, as later noted in a congressional investigation, poured thousands into Wood’s campaign.

But complications developed in Chicago, home to the 1920 Republican Convention. Others jumped into the presidential fray, including Illinois governor Frank Lowden. (Incidentally, the key Cook County coordinator of Lowden’s gubernatorial campaign had been his college friend Kenesaw Mountain Landis; some raised eyebrows would be appropriate.) The agreeable Wrigley, a delegate to the Convention from Illinois, actually voted for Lowden rather than for the initial leading vote-getter, Wood, nor third-place Johnson, both of whom he had funded. Harding, in fifth place far behind the top three on the first ballot, was supposedly selected by the political bosses in a smoke-filled suite at Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel. The key part of the deal was Lowden’s agreement to move his votes to Harding.

Lasker, more than Wrigley, was motivated by a specific issue: isolationism. Lasker cared most deeply about blocking American participation in the League of Nations. It is unclear how Wrigley felt about the issue. Lasker cuttingly said that Wrigley was a “one-idea man” who lived for Wrigley’s Chewing Gum. Lasker not only tried to force Harding into openly opposing the League as part of accepting the marketing assignment (no source even hints that Wrigley disagreed with Lasker on this), but also continued to pressure Harding on the issue throughout the campaign.

Wrigley later did articulate one political issue he cared about beyond the importance of being positive and working hard. When Calvin Coolidge became President after Harding’s death, Wrigley was a major proponent of Coolidge’s tax cut engineered by Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon. An enthusiastic Wrigley wrote that if Mellon sought the Republican nomination against Coolidge in 1928, he’d easily win. (Wrigley was a bit out of touch politically.) 15

Meanwhile in 1928, Lasker was trying to re-start the Hiram Johnson bandwagon against Coolidge’s re-nomination. Wrigley again funded Johnson’s 1924 campaign efforts before deciding that Coolidge was going to win re-nomination and was friendlier towards cutting taxes. Both men knew how to promote and advertise, but had severe political limitations.

Beyond those basic issues of opposing the League and desiring lower taxes, another even larger factor explains Wrigley’s and Lasker’s involvement in politics. The wealthy who get involved often have accomplished business success and are ready for some life changes. These people don’t necessarily abandon business involvement, but are wealthy enough that it no longer consumes them. For example, Lasker moved to Washington after the 1920 campaign because, substantially wealthy, he felt his business could succeed without his regular involvement.

Businessmen, often myopic in focus which leads to their success (i.e., Wrigley only thinking about gum), find politics intoxicating in multiple ways. The combination of power and victory after intense competition can intoxicate anyone, including the most famous movie stars, Wall Street financiers, and athletes. Wealthy businessmen with time to spare are not immune. Some, like Lasker, are heavily involved for a period while others, like Wrigley, are only marginally involved but stay engaged for a longer period.

Wrigley took his company public in 1919 and as a result suddenly came into even bigger stacks of cash. He remained President of Wrigley, and still dominated the gum world, but after the introduction of P.K. gum in 1921, his company introduced only one new product, a wartime gum, over the next 55 years. Product innovation was not his skill: Wrigley consolidated his products and promoted them hard. Cubs fans are probably not surprised. 16

But Wrigley personally was suddenly a changed man, as explained by his activities over a few short years after the IPO. Wrigley bought Catalina Island, Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, and the Angels PCL team as well as a mansion in Pasadena that his wife wanted mainly for its good seat from which to watch the Tournament of Roses parade. (The home is now Parade headquarters.) Wrigley also loved Phoenix and helped to grow it, investing in and eventually owning the famed Biltmore hotel. He also constructed an adjacent mansion, wintered in Phoenix, and encouraged millionaire friends to move there as well. Back in Chicago he built the iconic Wrigley Building and took over the Cubs. And helped elect a President. It was a busy few years. 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

Wrigley remained interested in politics. He was a delegate to the Republican National Conventions of 1924 and 1928. Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover both visited Catalina Island. During the three years of Harding’s Presidency, Wrigley visited the White House often enough to be listed as part of Harding’s “Poker” Cabinet but largely withdrew from politics except for providing some funding and friendship to various Presidents. Among Harding’s last words were the wish to do some deep sea fishing at Wrigley’s Catalina Island home. 21 , 22

Lasker’s involvement with President Harding was far more intense. He headed an agency that following World War I was very important: the National Shipping Board. It oversaw what to do with excess Navy vessels and the nation’s shipyards and oversaw America’s new role as the dominant power on the seas—a personal interest of Harding’s. Mrs. Harding adopted Mrs. Lasker as well. As a result, the Laskers ate at the White House three to four times a week. On a long vacation trip to the South, the Laskers joined the Hardings. Lasker complained, in fact, of having to play golf with Harding so often that his arms hurt.

During the campaign, Lasker had been called on to “fix” a number of Harding’s numerous personal problems. Another strong indicator of Lasker’s loyalty to Harding was his financing a significant percentage of the support for Harding’s mistress Nan Britton (and their child) after Harding’s death.

Lasker left Washington for a number of reasons, including his frustration with the never-ending negotiations of politicians and the fickle public, which couldn’t just be ordered to do things. He also didn’t care for Harding’s successor, Calvin Coolidge (a feeling which likely was reciprocated). Furthermore, Lasker’s business needed his attention again.

Often ignored in discussions of Lasker is the difficulty at the time of being Jewish. Lasker fully utilized his Jewish connections in the movie industry, baseball, and finance. Part of the reason he has not received his historical due is that he was forced to understate his involvement in the campaign.

Henry Ford wrote, in 1920, an article titled the “Jewish Degradation of American Baseball,” which became part of a book published during the campaign year titled The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem . 23

Ford blamed the world’s problems entirely on the Jews, focusing especially on Jewish influences in baseball. He claimed that “the Jewish coterie in Chicago” manipulated the “Gentile boobs” and led to the Black Sox scandal. Ford included a direct attack on Lasker and the plan to remove Ban Johnson. “Then it was that the Jew lawyer, [Alfred] Austrian (attorney for both Lasker and Charles Comiskey, also feuding with Johnson at the time), came forth with the ‘Lasker Plan,’ named for his Jewish friend Lasker, member of the American Jewish Committee, head of Lord & Thomas (Gentile names) and Chairman of the United States Shipping Board.” Ford’s article just goes downhill from there.

Lasker also faced rough grilling in Washington, but Harding not only stuck with him but also appointed him to a highly visible position. In fact, Albert Lasker was only the third Jew in history to hold a high post in American government. While Lasker went to the background, he obviously was not overly intimidated; just a few years later, he was again promoting Hiram Johnson for President.

It is clear that from the ownership days of Albert Spalding and his political involvement to the modern-day Ricketts family, politics and baseball have long been part of the Chicago Cubs tradition.

MARK SOUDER resides in Fort Wayne, Indiana, which he represented in the United States Congress for 16 years. An active leader during the baseball steroids hearings, Souder criticized one slugger for refusing to talk about the past to an oversight hearing but then told a famous pitcher, “It is better not to talk about the past then to lie about the past.”

NOTES

1 Morello, John A ., Selling the President, 1920: Albert D. Lasker, Advertising, and the Election of Warren G. Harding . Westport, CT: Praeger, 2001.

2 Crunkshank, Jeffrey, and Arthur Schultz, The Man Who Sold America: The Amazing (but True!) Story of Albert D. Lasker and the Creation of Advertising. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2010.

3 Gunther, John Taken at the Flood: The Story of Albert D. Lasker . New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960.

4 “Will H. Hays,” entry at IMDb.com

5 Roman, Kenneth . “Present at the Birth of Modern Advertising: The world of ‘Mad Men’ was really brought to you by a Chicago-based agency and its mercurial founder,” Wall Street Journal , July 30, 2010.

6 Troy, Gil, “Money and Politics: The Oldest Connection,” Wilson Quarterly, Summer 1997.

7 Russell, Francis. The Shadow of Blooming Grove: Warren G. Harding and His Times. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968.

8 Hall, Sheryl Smart, Warren G. Harding and the Marion Daily Star: How Newspapering Shaped a President . Gloucestershire, UK: History Press, 2014.

9 “Wrigley Owns Chicago Cubs: Acquires Holdups of Albert Lasker After Disagreement,” The Hamilton (Ohio) Journal-News, June 6, 1925.

10 “Wrigley Buys More Chicago Cub Stock,” Harrisburg (PA) Telegraph, June 6, 192 5.

11 Information found on Wrigley.com/global

12 Bachelor, Bob, “Corporate Innovators: William Wrigley,” from The 1900s. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company, 2002.

13 Morello, John, “Albert Lasker, 1880-1952,” at immigrantentrepresneurship.org. Written June 8, 2011, updated June 26, 2013.

14 “Albert Lasker, Marketing Master: Young advertising upstart becomes Founder of Modern Advertising,” Dictionary of Leading Chicago Businesses (1820—2000), prepared by Mark R. Wilson, at hardtofindseminars.com.

15 Boxerman, Burton A., and Benita W. Boxerman, Jews and Baseball: Volume 1, Entering the American Mainstream, 1871-1948 . Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing, 2006.

16 Golenbock, Peter. Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs . New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2007.

17 Mannering, Mitchell, “The Sign of the Spear: The Story of William Wrigley, Who Made Spearmint Gum Famous,” National Magazine , 1912.

18 Clark, S.J. Duncan, “Then Tell the World: This is William Wrigley, Jr’s Formula for Success,” Illustrated World , 1922.

19 “Four Buildings and a Funeral—Wrigley: The Architecture that Remains after a Great Company Dies,” found on Architecture Chicago Plus website

20 “Wrigley Jr. and Veeck Sr.” found on WrigleyIvy.com

21 Lower, Richard Coke, A Bloc of One: The Political Career of Hiram W. Johnson , Stanford University Press, 1993.

22 Greene, Frank, “The Day Harding Died,” from Essays, Papers & Addresses, found at the Calvin Coolidge Foundation

23 Krieger, Diane, “Treasured Island: Three Generations of Wrigleys have watched over the paradise that is Catalina Island,” USC Trojan Family magazine, Autumn 1999