Why Isn’t Gil Hodges in the Hall of Fame?

This article was written by John Saccoman

This article was published in 2002 Baseball Research Journal

Gil Hodges has received more votes for the Hall of Fame than any other person not selected. He came as close as 44 votes shy of election, but unfortunately, that came in his last year of eligibility under the BBWAA vote.

Gil Hodges’ Hall of Fame fate resides in the hands of the newly constituted Veterans Committee. Much time and energy has been devoted to the Hall, and many fans have opinions about unqualified players who have been inducted and vice versa. Noted Sabermetrician Bill James wrote a book, The Politics of Glory, detailing the history of the HOF, and presenting some arguments about which players might or might not merit selection. I will use his 15-point list of arguments as a guideline for Gil Hodges’ case. No one argument makes an entire case, but it is interesting to see how many can be used in Hodges’ favor. The numbering is based on James’ list:

3. Was he the best player in baseball at his position? Was he the best player in the league at his position?

This is probably the best argument for Hodges’ induction. He was the best first baseman in the NL in the fifties (if we consider Stan Musial an outfielder), and possibly the best in the majors. Hodges led all first basemen of the 1950s in the following categories: HR (310), G (1,477), AB (5,313), R (890), H (1,491), RBI (1,001), TB (2,733) and XBH (585). He made the All-Star team eight times, every year from 1949 to 1955 and again in 1957, the most of any first baseman of the time (again, discounting Musial). Hodges won the first three Gold Gloves at his position and was considered the finest defensive first baseman of the era as well. In addition, he was second among all players in the 1950s in HR and RBI, third in TB and eighth in R (fourth in NL).

Hodges was voted by respected baseball statistics organization STATS Inc. as the best defensive first baseman of the 1950s. The organization also retroactively selected All-Star teams for all years, both leagues. Hodges was named the retroactive All-Star first baseman four times, tying him for 13th place in number of times selected as a first baseman. Ahead of Hodges and in the Hall are Brouthers, Gehrig, Mize, Anson, Cepeda, Chance, Foxx, Sisler, and McCovey. The only players in the top twelve not in the Hall are Keith Hernandez and Ed Konetchy, while Hall of Fame first basemen such as Tony Perez, Jim Bottomley, and George “Highpockets” Kelly merited fewer STATS, Inc. selections.

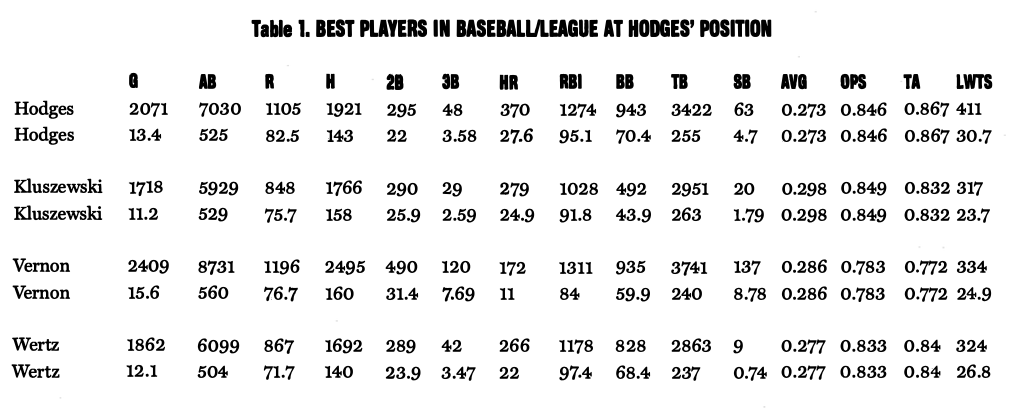

In the first edition of The Historical Baseball Abstract, James wrote, “The fifties were packed with first basemen who were outstanding for a few years but none was consistently strong throughout the decade.” He also states that Kluszewski, Hodges, and Vic Wertz were the contenders for the best first baseman of the decade. Hodges outpaces them in Boswell’s Total Average (a base-out percentage) and in Palmer/Thorn’s basic Linear Weights. Table 1 gives the player’s career totals, and then his numbers on a per/154 game basis.

(Click image to enlarge)

4. Did he have an impact on a number of pennant races?

In Hodges’ first ten years as a starting player, the Dodgers finished as low as third only twice, finishing in first place or tied for first six times. Hodges created a significant percentage of his team’s runs in the years 1948-1959. By Bill James’s Basic Runs Created formula, he created 12.3% of the Dodgers’ runs over that time. Over a similar period in his Reds career, Hall of Famer Tony Perez created just under 12% of his team’s runs.

Although this category seems to be more about contributions of players, Hodges also played a major role in the 1969 pennant race as the manager of the Miracle Mets. The seven-year-old expansion team, which had finished in 9th place at 73-89 the previous year, won 100 games despite having only two players (Cleon Jones and Tommie Agee) who had more than 400 at-bats.

5. Was he a good enough player that he could continue to play regularly after his prime?

Hodges drove in 100 runs in the seven consecutive seasons from 1949 to 1955. He continued to play as a regular for four years after that, averaging more than 26 home runs and 82 runs bat ted in for each of those years. It is clear that he was somewhat past his prime, but he continued to play regularly; he won his Gold Gloves in the last three of those years, the first ever awarded.

6. Is he the very best player in baseball history who is not in the Hall of Fame?

At the time of his retirement, Hodges was the leading right-handed home run hitter in National League history and also the league’s all-time leader in grand slams. Forgetting ineligible players such as Shoeless Joe Jackson, and sure-thing first ballot players, or arguably deserving players whose fate still resides with the BBWAA, the fact that he received the greatest number of HOF votes of any player may qualify him as the very best player not in the Hall who is under the purview of the Veterans’ Committee. His candidacy seems almost snake bit; according to sever al reports, Hodges missed selection by that committee by a single vote in 1992. Although we have no way of knowing how he would have voted, or whom he might have influenced, it should be noted that the late Roy Campanella, a former Hodges teammate, was too ill to attend that particular meeting.

7. Are most players who have comparable statistics in the Hall of Fame?

In The Politics of Glory, James makes compelling arguments based on similarity scores, i.e., determining players’ similarities based on career offensive totals and deducting points from 1000 for various differences. According to James, the nine “most similar” players to Hodges, none of whom are in the Hall of Fame, are as follows: Joe Adcock, Norm Cash, Rocky Colavito, George Foster, Willie Horton, Frank Howard, Lee May, Boog Powell, Roy Sievers. However, by James’s own system for determining if a player meets the standards of the Hall, Hodges scores the highest. From this group, only Joe Adcock was both a contemporary of Hodges and a pure first base man. Hodges outpaces Adcock in both the bat and the field, and he compares favorably with May and Powell, also first basemen. The player whose batting record is strikingly similar to that of Hodges is Norm Cash, but he certainly was not Hodges’ match in the field, and observers at the time saw fit to name Cash to only four All-Star teams. Also, Cash’s best season was 1961, the year of baseball’s first expansion and thus a year in which batting statistics were affected. Thus, Hodges can be seen as a first among equals.

To many, the player most similar to Hodges, and the one whose election to the Hall of Fame would most definitely seem to bode well for Hodges, is Tony Perez. Despite more than 2,700 more at-bats for Perez, their career numbers are similar (Hodges: 370 HR, 1,274 RBI, .273 BA, .361 OB, .487 SLG, 8 All-Star selections; Perez: 379, 1652, .279, .344, .463, 7). Also, they played the role of first baseman/RBI man deluxe on one of the best teams of their times. Each had two seasons over .300 batting average, and seven 100+ RBI years, although Gil Hodges had six seasons of 30+ HR to Perez’s two. These facts would seem to indicate that while the careers were somewhat equal, Hodges maintained a higher peak.

During his peak years as measured by those with an offensive HEQ (see point #8 below) greater than 300, Hodges’ teams had a winning percentage of .591, while Perez’s was .576.

However, in his most recent version of the Historical Baseball Abstract, James ranks Tony Perez as the 13th best first baseman of all time, and Hodges as the 30th. Is Perez really better than Hodges, and if so, is he that much better?

As mentioned above, the raw numbers for these two players are fairly similar. The only argument against Hodges might be that his career (1947-1962, with a cup of coffee in 1943) occurred during a time of relatively more offense than that of Perez (1964-1986). When viewed in context, Hodges slugged 23% better than his league over the course of his career, while Perez slugged 24% better than his. If we adjust for this, Hodges’ Slugging Percentage becomes only 1 point lower than that of Perez, .457. In addition, Hodges seems to have been a much more highly regarded defensive player, as Perez never won a Gold Glove. Thus, it would seem that Hodges and Perez are fairly close, and in fact, Hodges is in fact the better player when defense is taken into account.

8. Do the player’s numbers meet the HOF standards?

James developed several systems for enumerating the de facto HOF standards, and Hodges performs better in some than in others. Comparing him to his contemporaries, considering statistics of other first basemen in the Hall, and if his work as the manager of the Miracle Mets is also in the mix, Hodges meets or exceeds the Hall of Fame standards.

In his 1981 book, Baseball’s 100, Maury Allen gives Hodges one of 10 honorable mentions, thus placing him in his top 110 of all time. Interestingly, 17 of the 110 (including Hodges and Shoeless Joe Jackson) are not enshrined in the Hall.

Michael Hoban, in his book Baseball’s Complete Players, develops a statistical system to rank players based on on-field performance over the ten best seasons of his career. Hodges scores very well here also; Hoban asserts that a combined 830 PCT (Player Career Total) seems to be the “dividing line” for Hall of Fame induction, and Hodges’ score is 902. Hall of Fame first basemen Frank Chance (572) and Highpockets Kelly (805) miss the cut, while Cepeda (890), Bottomley (857), and McCovey (839) make the cut but score lower than Hodges.

9. Is there evidence to suggest that the player was significantly better or worse than suggested by his statistics?

The election of Tony Perez to the Hall shows that the role of the first baseman as a primary run producer, de-emphasizing batting average, is gaining increased recognition. There is a definite bias in the Hall toward players of high batting average, but is anyone prepared to defend the merits of 1920s HOF first baseman George Kelly’s six seasons batting over .300 vs. Hodges’ and Perez’s HR and RBI tallies? Hodges’ career Total Average (Tom Boswell’s base-out percentage), a statistic that displays no bias toward a particular style of player, is more than 100 points higher than Kelly’s (.866 to .749).

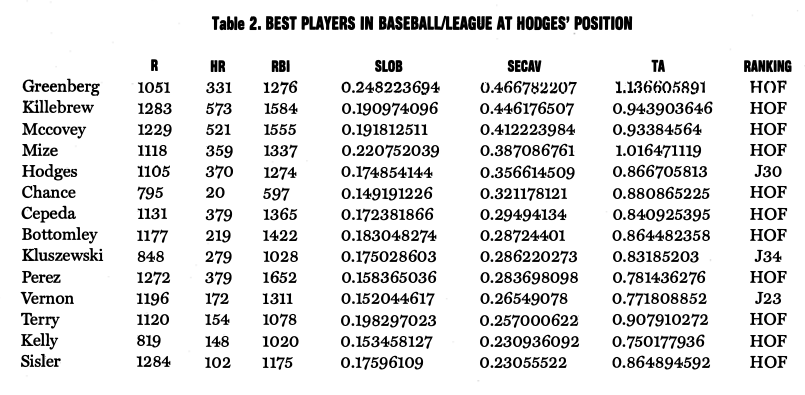

In his 2001 version of the Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James discusses the importance of “Secondary Average” as a statistic. “The things a hitter can do to help his team can be summarized in two more or less equal groups: Hitting for average, and everything else.” Secondary average is a statistic that attempts to measure the number of bases beyond a single that a player is responsible for. It is computed by taking Total Bases minus hits plus walks and steals, and dividing that total by the number of at bats. In a sampling of 15 first basemen throughout history, whether in the Hall of Fame, ranked ahead of Hodges in the Historical Abstract, or a contemporary of his, Hodges ranks fifth in secondary average, ahead of 7 of the Hall of Famers (see Table 2), seventh in Boswell’s Total Average (ahead of Sisler and Bottomley), ninth in Slugging Average times On Base Average (SLOB) (ahead of Cepeda, Perez, Kelly and Chance), and ninth in RBI.

Note that Lou Gehrig and Jimmy Foxx are not included, as they are far better than the players listed here and present an unfairly high Hall of Fame standard.

(Click image to enlarge)

10. Is he the best player at his position eligible for the Hall of Fame who is not in?

All the previous arguments suggest that Hodges is the best player and best first baseman not honored with a HOF plaque whose fate is in the hands of the Veterans Committee.

11-13. How many All-Star teams? How many All-Star Games? Did most players in this many make the HOF?

As previously stated, Hodges made eight All-Star teams. Counting two All Star teams in the same year when the players were boosting their pension fund (1959-1962) as a single nomination, the following Hall of Famers made a comparable number: Duke Snider, 8; Willie Stargell, Tony Perez, Juan Marichal, Bill Mazeroski, 7; Billy Williams, Ralph Kiner, 6; Phil Rizzuto, Richie Ashburn, 5.

Here are the members of his “similarity cluster ” and their number of All-Star selections: Joe Adcock (1), Norm Cash (4), Rocky Colavito (6), George Foster (5), Willie Horton (4), Frank Howard (4), Lee May (3), Boog Powell (4), Roy Sievers (4). Colavito and Hodges are the only ones to distinguish themselves from the pack in this category.

14. What impact did the player have on baseball history?

Gil Hodges was a key contributor to the second-best team of the 1950s and a beloved figure in his adopted home of Brooklyn. He was the manager of the Miracle Mets, one of the most unlikely World Series Champions in baseball history.

15. Did the player uphold the standards of sportsmanship and character that the HOF, in its written guidelines, instructs us to consider?

This is another very strong point in Hodges’ favor. The strong, silent type, he was described in Pete Golenbock’s Bums as “the Dodgers’ Lou Gehrig … strong but sphinx like, more of a presence than a personality. … Everything Hodges did was professional. … Off the field he was a gentleman and a gentleman.” The same book quotes the Dodgers’ public relations man Irving Rudd as saying, “If I needed a player to visit a blind kid in the stands, a kid in a wheelchair,” Hodges would be there. This man was beloved by fans; in his epic Boys of Summer, Roger Kahn entitled the chapter about Hodges “the one who stayed behind.” Unlike most players, Hodges actually won the hearts of fans when he went into a slump that began in the 1952 World Series and continued into the next season.

That Hodges has positives in 11 of the 15 arguments that James feels to be valid is a strong indication that he merits induction in the Baseball Hall of Fame. In his time, he was the best at his position, offensively and defensively. Peripheral considerations that bolster his case include his character, his role in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ only World Championship (drove in both runs in the 2-0 clincher, fielded the throw from Pee Wee Reese for the final out), and his role as architect of the Miracle Mets.

The other categories offered by James include number of times leading the league in a major category (which Hodges never did), MVP awards (for which he received puzzlingly low support) and rules or equipment changes brought about as a result of the player. Hall of Fame voters are asked to consider six criteria when evaluating a candidate’s worthiness for enshrinement. In no particular order, they are record, ability, character, sportsmanship, integrity, and contribution to the game. We have addressed Hodges’ record, ability, and contribution to the game. His character, sportsmanship, and integrity are more difficult to quantify. However, Hodges was never ejected from a game, and by all accounts, he was highly regarded. In the Historical Abstract, James quotes Arnold Hano about Hodges, “He was a patient, devoted man with a fine heart.”

JOHN T. SACCOMAN teaches in the Seton Hall University Department of Mathematics and Computer Science. Born after Gil Hodges retired, he only recently learned that Hodges was his late grandfather’s favorite player.