Why Were the Dodgers Teams of the 1960s So Good?

This article was written by John G. Zinn

This article was published in Dodger Stadium: Blue Heaven on Earth (2024)

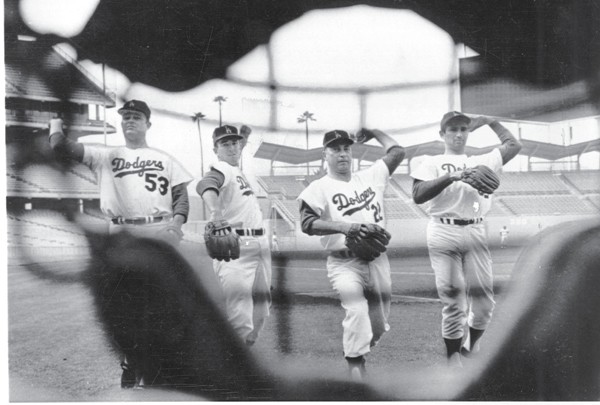

L to R: Don Drysdale, Claude Osteen, Johnny Podres, and Sandy Koufax, 1964. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Why were the Dodgers teams of the 1960s so good? Readers will be excused if their knee-jerk answer to the question is just two words – Sandy Koufax. Since the left-hander went 111-34 over his last five seasons with a 1.95 ERA, it’s a perfectly understandable response. But even though baseball may be more of an individual game than other team sports, success at the highest level requires more than one or two great players. And so it was with the Los Angeles teams that in the same five-year period won three pennants, lost another in a tiebreaker and won two World Series. Perhaps surprisingly, the key to understanding the Dodgers’ success can be found in the wreckage of the team’s epic 1962 failure or rather in how they responded to that failure. While the 1962 team had Koufax for roughly only half of a season, the rest of a strong staff led by Don Drysdale, along with an offense that averaged five runs per game, put the Dodgers four games ahead with only seven to play. Needing just two wins to clinch the pennant, Los Angeles managed only one victory, enabling the Giants to gain a tie on the season’s final day.

After splitting the first two tiebreaker games, the Dodgers rallied to take a 4-2 lead after seven innings of the deciding game. When Los Angeles reliever Ed Roebuck faced only three Giants hitters in the eighth, it looked as though the Dodgers were home free. However, disagreements broke out in the Dodgers’ dugout, with players and third-base coach Leo Durocher arguing that Walter Alston should bring in Drysdale to get the final three outs. According to Maury Wills, Alston refused solely because it was Durocher’s idea.1 The chaos in the dugout spread to the field, where the Giants were handed four runs on only two hits, thanks to four walks, an error, and some controversial defensive positioning.2 While longtime Dodgers fans may consider 1951 worse, veteran sportswriter Dick Young, who covered both, claimed 1962 was “much worse.” Indeed, Young called it “the biggest apple [choke up] in the history of big-league ball.”3 The sentiment was echoed by his colleague Jimmy Powers, who said the Dodgers “choked” so badly that there was “no euphemistic way of saying it.”4

What’s important for our purposes is Powers’ further comment that the Dodgers lost because of an “almost incredible exhibition of futile major league baseball.”5 In 1951, it could be argued, the Giants won the pennant, while in 1962 the Dodgers lost it. It would not have been at all surprising for such an epic failure to have a damaging carryover effect. In this case, however, the lessons learned from the 1962 disaster enabled the Dodgers to find an identity that helped them win three pennants and two World Series in four years. It was an identity built first on pitching excellence that began with, but was not limited to, Koufax. Pitching excellence that was strengthened and complemented by Buzzie Bavasi’s strategic roster-building, Walter Alston’s managing, Maury Wills’ leadership, and “finishing” crucial games.

The 1962 disaster notwithstanding, Los Angeles, with a healthy Koufax, plus Drysdale, Podres, and Perranoski, already had a good pitching staff. However, general manager Bavasi used the 1962 offseason to begin building something special by replacing Stan Williams with Bob Miller. Williams, who walked in the winning run in the third playoff game, had, deservedly or not, become the poster boy for the 1962 failure. His wildness at that crucial time, however, was symbolic of his consistently inconsistent control. According to Drysdale, Alston couldn’t abide a lack of control so a pitcher would “either throw strikes or be gone.”6 While getting rid of Williams was understandable, replacing him with Miller and his 1-12 record and 4.89 ERA did nothing to impress Frank Finch of the Los Angeles Times, who sarcastically said the trade “fell far short of upsetting the balance of power in the National League.”7 Bavasi, however, had liked Miller for several years, an opinion supported by Dick Young, who saw Miller on a regular basis and dubbed him “the best 1-and-12 pitcher in baseball.”8 Bavasi’s faith in Miller was rewarded as the right-hander proved a competent fourth starter in 1963 and went on to become an important part of the Dodgers’ very deep bullpen. Nor was this the last time Bavasi found overlooked or undervalued talent.

Los Angeles redeemed the 1962 failure by winning the 1963 National League pennant and the World Series, but a year later, the Dodgers finished in a disappointing sixth-place tie. In response, Bavasi demonstrated beyond any doubt his belief that pitching excellence was the team’s core identity. In a trade with the Washington Senators, Bavasi gave up power (Frank Howard and Ken McMullen) for pitching and defense (Claude Osteen and John Kennedy). Not appreciating or understanding what Bavasi was doing, Sid Ziff of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the Dodgers general manager “went bear hunting again and came back with a couple of squirrels.”9 In response, the Dodgers GM argued that “[i]f you can improve your defense and pitching you can accomplish the same thing [as adding more power].10 While Kennedy was not the answer at third, Osteen stepped in just as Johnny Podres’ career was winding down. On three occasions in 1965, Osteen was an invaluable stopper, especially in the World Series, when his third-game shutout saved the Dodgers from a possible insurmountable three-games-to-none deficit.

Bavasi’s final major pitching acquisition appeared to be so insignificant that it understandably attracted little attention. After winning the 1965 pennant and World Series, he traded Dick Tracewski to Detroit for right-hander Phil Regan. In a six-year major-league career as a starter, Regan had a mediocre 42-44 record with an ERA over 4.00. His performance was so underwhelming that he spent most of 1965 in the minors. As with Bob Miller, however, Bavasi saw something others missed.11 Regan, whom Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray called “just another faceless American League spot starter,” performed so well for the 1966 Dodgers pennant-winning team that he received the National League Comeback Player of the Year Award.12 Bavasi and the Dodgers also strengthened their pitching staff from within, especially through the 1966 addition of future Hall of Famer Don Sutton.

While Los Angeles’ major acquisitions primarily strengthened the pitching staff, there was another trade whose value exceeded everyone’s expectations, most likely including Bavasi. In April of 1964, the Dodgers traded Larry Sherry to Detroit for Lou Johnson, the ultimate journeyman who played for so many teams it’s hard to keep track. Johnson was considered of so little significance that the deal was described as the “sale of relief pitcher Larry Sherry.”13 When Tommy Davis, the Dodgers’ best hitter, suffered a season-ending injury on May 1, 1965, Johnson took his place. He went on to hit .320 in “close and late games” and .300 against the Giants and Reds, the two teams immediately behind the Dodgers. His contributions also included a game-winning home run in the stretch run and a key homer in the seventh game of the World Series. Johnson and home-grown players like Wes Parker and Jim Lefebvre were not superstars, but they still made important contributions to the Dodgers success.

Just how excellent was the Dodgers pitching? In winning three pennants, Los Angeles hurlers led the league in ERA and shutouts while finishing near the top in strikeouts, fewest home runs allowed, and complete games. Also important was the durability of the four-man starting rotation. In 1963 the top four started 86 percent of the team’s games, which grew to 90 percent in 1965 and a hard-to-imagine 95 percent in 1966. During those last two seasons, the top four starters of the Giants, the Dodgers’ main rival, managed only 72 percent and 76 percent respectively of games started. It was a major advantage for Los Angeles in two pennant races that were decided on the last weekend of the season.

And when the starters didn’t deliver a victory, the team could rely on relievers who not only saved games but won when the starters couldn’t finish the job. In 1963 and 1966 Perranoski and Regan contributed not only saves (21 each), but wins, 16 by Perranoski in 1963 and 14 by Regan in ’66.. In over 75 percent of those wins, the two Dodgers relievers entered the game either with the score tied or their team behind. They were effectively carrying on almost like a second starter until the offense scored enough runs. It was an invaluable additional form of depth for a team built on pitching excellence.

There is no better illustration of the LA pitching staff’s excellence than the 1965 and 1966 pennant races. On September 15, 1965, the Dodgers were in third place, 4½ games out of first with just 16 games to play. Los Angeles then won 14 of its next 15 games to come from behind and win the pennant. During that streak, Dodgers pitchers threw seven shutouts and allowed just 14 earned runs for an ERA of 0.90. Surprisingly, the worst performance was by Koufax, who allowed five of the 14 runs in one game. Drysdale had the best ERA among the starters at 0.28, while Perranoski in 20⅔ innings of relief didn’t allow a single earned run. While the 1966 performance wasn’t quite as dominant, it was just as effective. In third place on September 7, Dodgers pitchers threw four straight shutouts to begin an eight-game winning streak with a combined staff ERA of 1.11. The streak put the Dodgers in first to stay.

Winning the pennant was, of course, not the ultimate challenge. That came in the World Series, especially in 1963 when the Dodgers faced a Yankees dynasty that had won nine Fall Classics in 14 years. Koufax knew exactly what he was up against when he saw how “pre-series reports, especially in New York, had become a tribute to the Yankee dynasty.”14 His challenge in the first game was “to show myself and my team, and the Yankees too, that they were just a team of baseball players, not a pride of supermen.”15 The challenge couldn’t have been met any more completely. The Dodgers ace struck out the first five Yankees on the way to setting a World Series record of 15 K’s in a game.16 Koufax’s dominating performance set the tone for the Dodgers’ four-game sweep, in which the Yankees managed only four runs. The task in 1965 was far more difficult, especially after the Twins defeated both Drysdale and Koufax in succession. At this point, the Dodgers’ pitching depth came to the rescue when Osteen shut out Minnesota in Game Three, only the fourth time the Twins were shut out all season. Having avoided the abyss, the Dodgers won three of the next four, featuring two Koufax shutouts. The Dodgers staff shut out the Twins as many times in one week as the entire American League did in a season.

No pitching staff, even one like the Dodgers, runs itself. According to Drysdale, Alston ran the Los Angeles staff, and ran it well. If “the greatest strength a manager can have is knowing his pitchers,” the Dodgers right-hander said “… Walt knew us like the back of his hand.”17 While the Dodgers always had a pitching coach, Alston supposedly took charge of the pitching staff once the regular season began.18 Just one example of how Alston effectively handled his pitchers is his visit to the mound when Koufax was struggling in the seventh game of the 1965 World Series. Rather than telling his ace what to do, the Dodgers skipper simply reminded Koufax to “pitch your normal way” in order to avoid the mistakes that pitchers often make when they “try too hard.”19

Much of the praise given to Alston came after the Dodgers manager received scathing criticism for his handling of the team’s pitchers in the ninth inning of the deciding game of the 1962 playoffs. Roseboro, Durocher, and – according to Durocher – Koufax, Drysdale, and Podres all criticized Alston for allowing Roebuck to start the ninth inning, for not taking him out sooner and for bringing in Williams instead of Perranoski or Drysdale.20 According to both Durocher and Roseboro, Alston “played everything conservatively” and “by the book.”21 Alston himself, in an interview a few years later, said he thought of himself as “a ‘percentage’ manager.”22

Whether Alston modified his approach after 1962 or he wasn’t as conservative as some claimed, he could and did manage aggressively. A case in point is a crucial September 1, 1963, game with the Giants at Dodger Stadium. After using some unorthodox moves to help his club gain a 5-3 lead going to the ninth, Alston not only brought in Podres in relief for the first time in two years, he did so against four consecutive right-handed hitters. The move worked, earning Alston praise from Curley Grieve of the San Francisco Examiner, who wrote that the manager’s moves were “why the Dodgers won their biggest game of the season.”23 The loss left the Giants reeling and on their way out of pennant contention.

Despite his overall success as Dodgers manager, Alston had no shortage of critics, including some of his own players. Roseboro at least partially addressed such criticism when he declared that he “never knew a player who wasn’t critical of his manager.”24 What’s more impressive, however, is the consistent refrain of players like Drysdale and Roseboro as well as Bavasi about how easy it was to play for Alston. As Drysdale put it, “[I]f you couldn’t play for Walt, you might as well pack up your gear and find another line of work.”25

While winning pennants with dominant pitching and limited offense was not the preferred approach of the 1960s, it had been successful in earlier times. In retrospect, the Dodgers of that period were something of a throwback to the Deadball Era, 1901-1919. As such, Los Angeles was extremely fortunate to have an on-the-field leader in Maury Wills, who would have fit right in during the early twentieth century. According to sportswriter Bud Furillo, Wills “revolutionized baseball” by “[bringing] back the stolen base” along with “speed and daring.”26 In 1960 the Dodgers shortstop led the league with 50 stolen bases, which today may not seem that extraordinary. It was, however, the first time a National League player had reached the half-century mark since Max Carey 37 years earlier, in 1923. During those years, the average stolen bases for the league leader was a mere 30. In the same time frame going forward, the average jumped more than twice to 72, demonstrating that Wills’ “revolutionary” strategy was no temporary fad.27

Wills’ basestealing was crucial to the Dodgers’ offense, but his overall contributions to the Dodgers’ success cannot be measured by statistics alone. Wills’ approach to the game was like that of Hall of Famer Johnny Evers, one of the great players of the Deadball Era. In Wills’ book On the Run, he said that when he and Roger Craig were in the minors together, “We worked out plays on the bus from the hotel going to the ballpark. We talked about them in the dugout and the clubhouse.28 Those words are eerily similar to Evers’ lament in 1925 about how the game had “deteriorated” from the days when “we used to spend hours doping [figuring out] plays.29 Among Wills’ common practices was watching the other team take infield and outfield practice, something he claimed other players stopped doing once they reached the majors.30 His self-stated goal was to play baseball “not as well as I could play, but as well as it could be played.”31 Wills, the Dodgers’ captain in 1965 and 1966, had no bigger fan than Koufax, who said, “We cannot win without Maury Wills in the lineup.”32

While it’s harder to quantify than the other explanations of the Dodgers’ success, the team’s achievements in the mid-1960s can also be attributed to another lesson learned from the 1962 disaster. Reflecting on that failure, John Roseboro wrote, “We spent so much time looking at the scoreboard to see how the Giants were doing, we stopped doing for ourselves.”33 In the final analysis, the 1962 Dodgers failed to “finish” the job twice. First, by scoring only two times in their last three regular-season games when they needed only one win to “finish” the 1962 pennant race. And then, to make matters worse, needing only three outs to “finish” the playoff series with the Giants, chaotic decision-making and poor pitching lost the pennant for a second time.

It’s hard to envision a more painful lesson, and the Dodgers learned it well. During the 1963 pennant race, Los Angeles won crucial games against the Giants and the Cardinals where a loss would have allowed their opponents to stay in the race. In the September 1 game mentioned earlier and a September 18 game with the Cardinals, Los Angeles won close contests without either Koufax or Drysdale. The two wins “finished” the opposition and avoided the need of any last-weekend dramatics. In 1965 and 1966, as in 1962, on the last weekend of the season, the Dodgers needed one win to “finish” the pennant race, and in both cases, they got it. Both times Koufax was on the mound, but it’s worth noting that in the 1966 game against Philadelphia, his teammates staked their ace to a 6-0 lead. As painful as the 1962 debacle was, it was a lesson well learned.

The decline of the 1960s Dodgers began when Sandy Koufax announced his retirement shortly after Los Angeles was swept by the Baltimore Orioles in the 1966 World Series. While it’s unlikely that the Dodgers could have quickly rebuilt or reloaded, management decisions greatly limited any such possibilities. At the top of the list was trading Maury Wills due to his leaving the team without permission during the ill-advised Japan trip. Although it happened earlier, insisting that Tommy Davis return prematurely from an injury that probably required a two-year recovery period was also a mistake. The Dodgers dropped quickly into the second division, and it wasn’t until 1971 that they again competed for a title. While the Dodgers of the 1960s were not a dynasty like the Yankees, they compare favorably to other dominant National League teams like the Cubs (1906-1910), the Giants (1921-1924), the Cardinals (1942-1946), and their Brooklyn counterparts (1952-1956). More than anything else, they were successful because they found their identity and fully embraced it.

JOHN ZINN is an independent historian with a special interest in the history of baseball. He is the chairman of the board of the New Jersey Historical Society and was the chair of New Jersey’s Committee on the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War. John is the author of five books including three about the Brooklyn Dodgers as well as numerous essays and articles. He also writes a baseball history blog entitled A Manly Pastime. John holds BA and MBA degrees from Rutgers University and is a Vietnam veteran. He is the scorekeeper for the Flemington Neshanock vintage baseball team. John and his wife Carol are the parents of Paul Zinn and the grandparents of Sophie and Henry Zinn.

Notes

1 Steve Delsohn, True Blue – The Dramatic History of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Told by the Men Who Lived It (New York: Harper Collins, 2001), 54; Leo Durocher with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975), 18-20.

2 David Plaut, Chasing October The Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race of 1962 (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1994), 183-84.

3 Dick Young, “Dodgers Lose, Giants Win to Force Playoff,” New York Daily News, October 1, 1962: 44, 47.

4 Jimmy Powers, “The Clubhouse,” New York Daily News, October 4, 1962: 83.

5 Powers, “The Clubhouse.”

6 Don Drysdale with Bob Verdi, Once a Bum, Always a Dodger (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990), 168.

7 Frank Finch, “Burright, Harkness Swapped for Miller,” Los Angeles Times, December 2, 196: 58.

8 “Burright, Harkness Swapped for Miller,” Dick Young, “Mets Snare Burright, Harkness for Miller,” New York Daily News, December 2, 1962: 146.

9 Sid Ziff, “Who Got Slickered?” Los Angeles Times, December 7, 1964: 45.

10 “Who Got Slickered?”

11 “Dodgers Trade Tracewski to Tigers,” Los Angeles Times, December 16, 1965: 49.

12 Jim Murray, “Phil Regan, the Man Who Came to ‘Vulch,’” Los Angeles Times, September 2, 1966: 41.

13 Frank Finch, “Dodgers May Add Brewer to Roster,” Los Angeles Times, April 10, 1964: 49.

14 Sandy Koufax with Ed Linn, Koufax (New York: Viking Press, 1966), 191.

15 Koufax, 191.

16 Bob Gibson set a new record of 17 strikeouts in a game in the 1968 Series.

17 Drysdale, 174.

18 Drysdale, 174.

19 Michael Leahy, The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers (New York: Harper Collins, 2016), 327.

20 Durocher, 19; John Roseboro with Bill Libby, Glory Days with the Dodgers and Other Days with Others (New York: Atheneum, 1978), 224.

21 Durocher, 16; Roseboro, 223.

22 Paul Zimmerman, “Dodgers’ Quiet Man Gets Job Done,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1966: 42.

23 Curley Grieve, “Alston’s Juggling Act Trips Dark,” San Francisco Examiner, September 2, 1963: 49.

24 Roseboro, 224.

25 Plaut, 29; Drysdale, 167; Roseboro, 226.

26 Delsohn, 49.

27 https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/SB_leagues.shtml.

28 Maury Wills and Mike Celizic, On the Run: The Never Dull and Often Shocking Life of Maury Wills (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1991), 83.

29 “Game Has Deteriorated Says Evers,” Pittsburgh Press, August 1, 1925: 9.

30 Wills, 129

31 Wills, 22.

32 Koufax, 245.

33 Roseboro, 202.