Women’s Baseball in Nineteenth-Century New York and the Man Who Set Back Women’s Professional Baseball for Decades

This article was written by Debra A. Shattuck

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

New Yorkers love baseball. Their passion for the national game (and its bat-and-ball precursors) can be traced back into the earliest decades of the nineteenth century. Prior to the Civil War, scores of juvenile and adult teams in New York vied for bragging rights or trophy balls on emerald fields and dusty lots.1 Boys and men weren’t the only ones reveling in the excitement of smacking hard grounders past pitchers or putting runners out by catching a lofty fly ball (or on the first bounce by some early rules); girls and women were playing too — in cities large and small and in villages scattered across the rolling hills of upstate and western New York.

In 1859 a 27-year-old dentist, Francis Guiwits of Steuben County, New York, informed Harper’s Weekly that baseball had been a popular game “in nearly all the villages and among the rural districts of Western New York” for at least twenty years. He added that baseball was “the game at our district schools during intermission hours, and often engaged in by youths of both sexes.”2

Earlier that year, newspapers in Albany, Troy, and Genesee County had debated the propriety of women playing baseball. One individual argued that “there seems nothing violent in the presumption that ball playing would prove as agreeable and useful to ladies as to gentleman,” while another retorted, “Bosh! Just think of looking for the ball every minute or two under the circumference of crinolined players.”3

Criticizing the assumption that women had to wear cumbersome clothing while playing baseball, the Troy Daily Times responded: “Humbug! As if a woman must at all times and under every circumstance, be arrayed in the stiff and conservative propriety of drawing room attire.”4 When an unnamed advocate suggested that women could wear bloomers while playing, the Troy editor countered: “We are no advocates of the Bloomer costume, but we can imagine that there are occasions on which short dresses, minus the outlandish pantaloons — in brief, a rig permitting the free and natural exercise of the lower limbs — would be worth[y], healthful and proper.”5

Fashion constraints weren’t the only thing deterring women from playing baseball in the nineteenth century. They also had to decide whether playing baseball was worth risking their fertility and their lives. Girls and women were inundated with warnings from physicians that they would be irreparably harmed if they overexerted themselves physically or mentally — particularly during or after puberty.

In October 1867 newspapers around the country reprinted an (erroneous) story that a 21-year-old woman in Allen’s Prairie, Michigan, had died after playing baseball.6 (Amaret Howard actually succumbed to typhoid fever.)7 That same year the Reverend John Todd warned about the dangers of encouraging women to ape men in their intellectual pursuits: “If it ministers to vanity to call a girl’s school ‘a college,’ it is very harmless; but as for training young ladies through a long intellectual course, as we do young men, it can never be done — they will die in the process.”8

Each girl and woman who threw herself into her academic studies or decided to pick up a baseball bat and dash around the basepaths in the mid-nineteenth century had to weigh the potential consequences of her actions. For the thirty-six young women at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, who organized three baseball clubs in 1866 and 1867, and for those who organized a junior and senior nine in Peterboro the following year, love of baseball outweighed warnings about infertility or death.9

In 1875, scores of students at Vassar College organized seven or eight baseball teams with the frightening pronouncements of Harvard Medical School physician Dr. Edward H. Clarke ringing in their ears. In his bestselling book, Sex in Education: Or, A Fair Chance for the Girls (1873), Clarke explained that youth needed to carefully regulate both “muscular and brain labor” so that their bodies had sufficient “force” available to manufacture their “reproductive machinery.”10 He ominously warned that young women who ignored his counsel risked “neuralgia, uterine disease, hysteria, and other derangements of the nervous system.”11

Fortunately for girls and women who loved to play baseball and to engage in other rigorous activities, there were also voices challenging Clarke’s proscriptions. Dr. Helen Webster was resident physician at Vassar College 1874–81. She encouraged students to keep playing baseball even after one of them injured her leg running the bases.12 Webster, like a growing number of physical fitness experts, understood the positive correlation between robust health and vigorous exercise. By the 1880s and 1890s, colleges across the country were hiring physical fitness instructors like Dudley Sargent and Senda Berensen, as well as building gymnasiums, swimming pools, and sports fields to promote athleticism and robust health in male and female students.

The new emphasis on athletics for women inspired more girls and women than ever before to try their hand at baseball — especially in New York state. During the 1870s, girls and women in Rhinebeck, Poughkeepsie, Brooklyn, Erie, Kingston, Auburn, Rochester, Phoenix, Syracuse, and New York City played on baseball teams. In the 1880s and 1890s, dozens more female teams sprang up in at least two dozen New York communities.13 Players came from all social strata. There were immigrants, like Maud Nelson, playing on New York-based barnstorming teams, black women, like Mary E. Thompson and Mary Jackson, playing on pick-up teams, and upper class girls and women, like those at Mrs. Hazen’s School in Pelham Manor and “society buds” in Greenwich, playing on scholastic and civic teams.14

There were so many women playing baseball by the mid-1880s that the New York World commented that sports like cricket and baseball were helping to “enlarge the sphere of the contemporaneous woman.” The World described the transition of the female athlete it was observing: “When the [contemporaneous woman] first took to base ball she was a little limp on the pitch and scattered a little on the home base. She caught a ball with her head over her shoulder, and had an abnormal fear of being struck below the belt. But these absurd things have passed away with development.”15

Girls and women played on the same types of teams as boys and men. In addition to school, college, civic, business, and pick-up teams, girls and women played on professional teams. The first women’s professional team was organized by men in Springfield, Illinois, in 1875, but many nineteenth-century women’s professional teams originated in New York City. They sported names like the Young Ladies Champions of the World Base Ball Club, the American Stars, the American Female Base Ball Club, the New York Giants, the Young Ladies Base Ball Club of New York, the New York Champion Young Ladies Base Ball Club, and even the deceptively named Cincinnati Reds.16

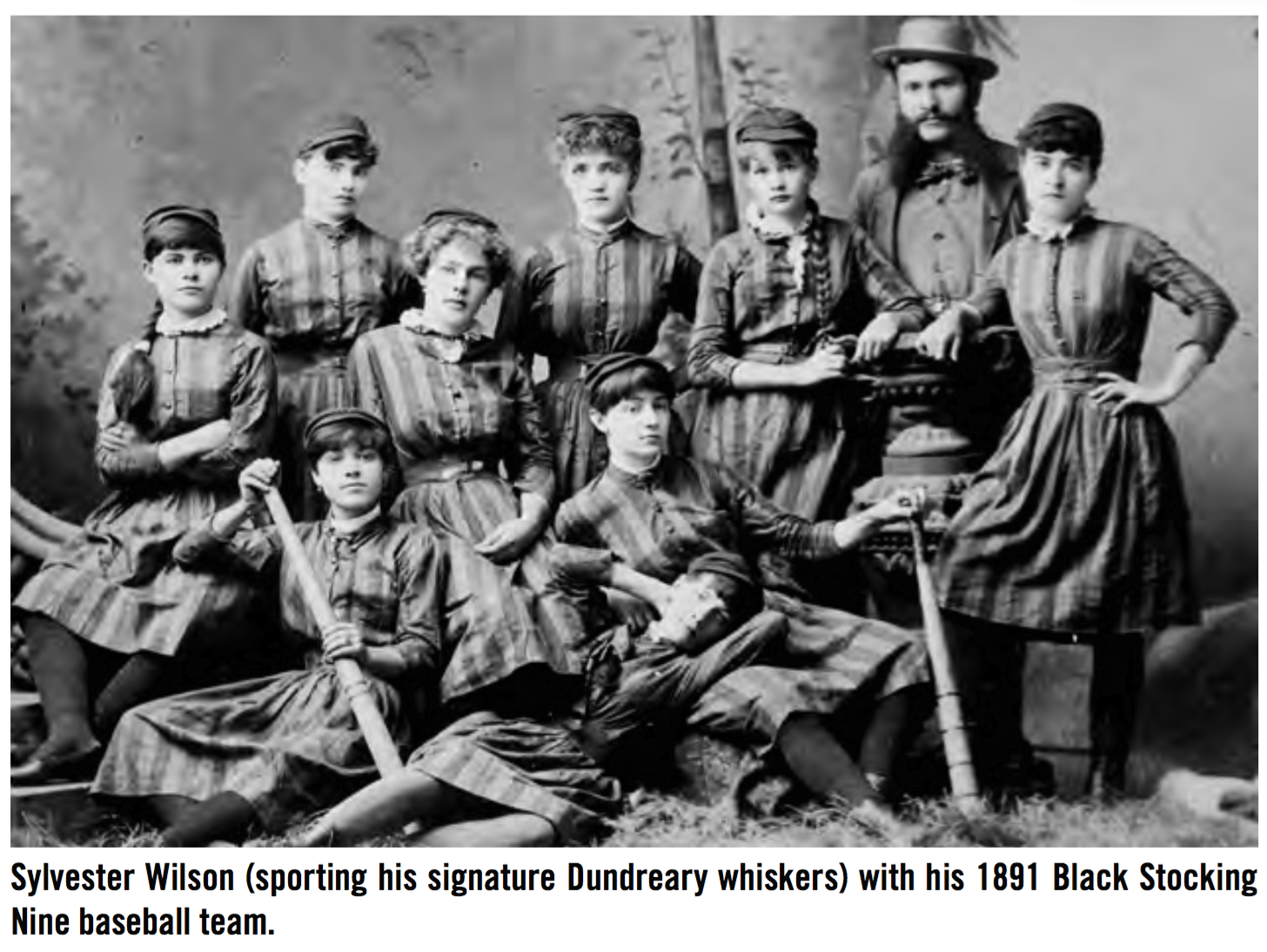

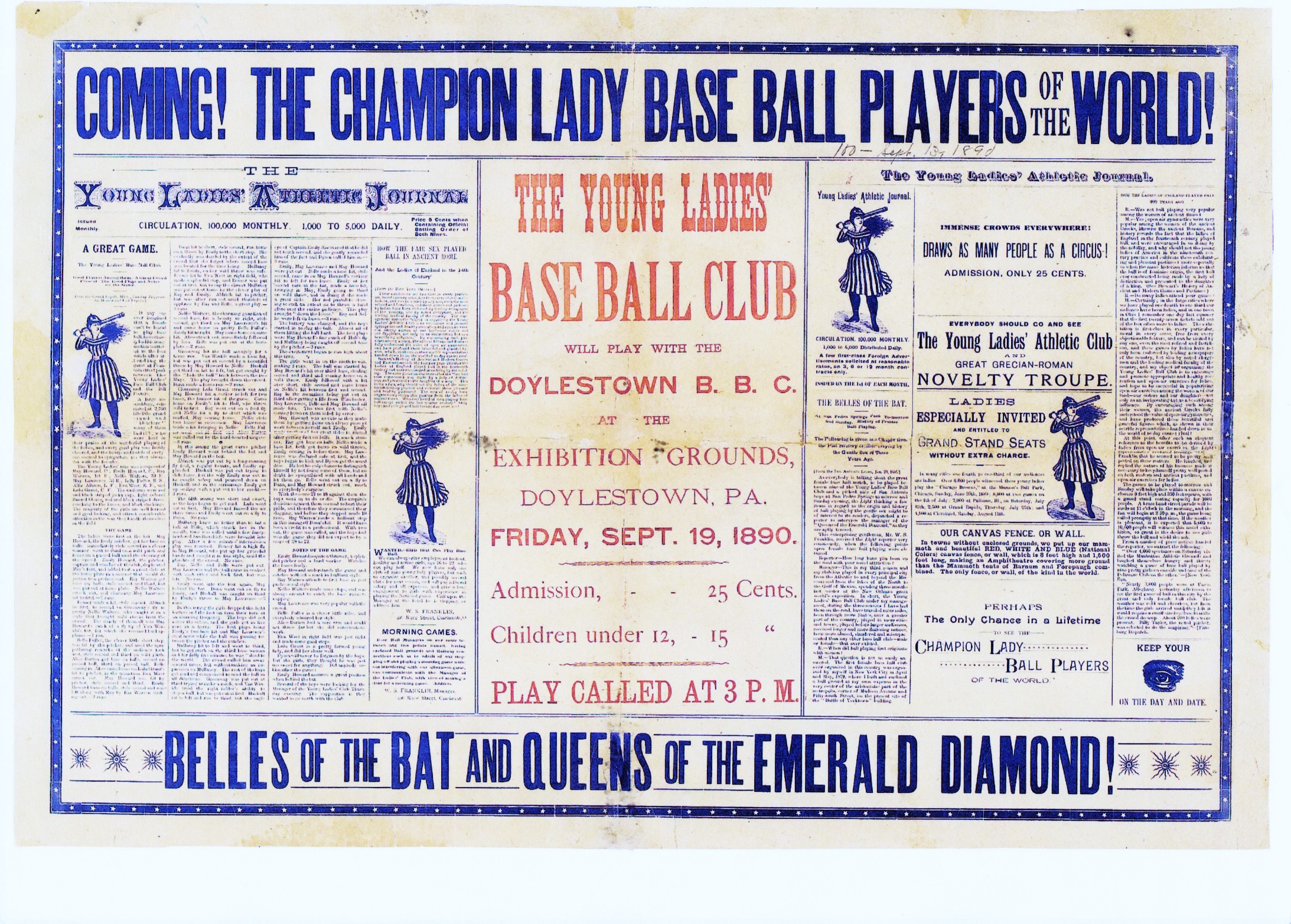

Sylvester Wilson Promotional Publication, The Young Ladies’ Athletic Journal, September 1890.

The earliest of the New York City-based female ball clubs was Sylvester F. Wilson’s short-lived American Brunettes and English Blondes, organized in late March of 1879.17 The team was short-lived because Wilson and his business partner, William Powell, were both arrested for “engaging girls under 16 for immoral purposes” and for having sexual relations with girls under 16.18

Wilson was the most notorious female baseball manager of the twentieth century. He was a narcissist, career criminal, and pedophile, and organized female baseball teams between 1879 and 1903 in places including New York City, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Chicago, and Cincinnati. James William Beul called New York City “the Great Maelstrom of Vice” in 1879 and Sylvester Wilson felt right at home in its seediest neighborhoods.19 Because he was continually running afoul of the law, Wilson used multiple aliases like H.H. Freeman, Harry Richmond, W.S. Franklin, and Frank W. Hartright to hide his identity from the police and child protective agencies like the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NYSPCC).20

Agents of the NYSPCC kept tabs on Wilson after his arrest for sexual impropriety in 1879 and were successful in bringing Wilson to justice on several occasions, including his arrest in August 1891 for allegedly abducting 15-year-old Libbie Agnes Sunderland from her home in Binghamton to join his barnstorming troupe. The Society not only brought the charges against Wilson in the Sunderland case but also compiled testimonies from individuals around the country detailing how Wilson had duped, defrauded, or ruined them.21 NYSPCC agents were delighted when Wilson received a five-year sentence to Sing Sing and $1,000 fine in 1892.

Two months after Wilson’s release from prison in August 1898, Society agents began receiving reports that Wilson was making unwanted advances on a 17-year-old store clerk. The following May, Manager Fred Smithson of the St. George cricket grounds in Hoboken, swore out an arrest warrant against Wilson (using the alias, William S. Franklin) and his partner H.A. Adams when they absconded with the gate receipts from a baseball game between their female baseball nine and the Hudson Athletic Club.22

Narrowly avoiding incarceration, Wilson headed for Philadelphia where he quickly attracted the attention of the Pennsylvania Society for the Protection of Children from Cruelty (PSPCC) on suspicion of being a “procurer” and enticing young girls from home. In its Twenty-Fifth Annual Report, the NYSPCC noted that it was “the pleasure of this Society to furnish from its records the complete criminal history of Wilson” to the PSPCC so it could prosecute Wilson.23 Just over a year after walking out of jail in New York, Wilson was imprisoned in Pennsylvania’s Moyamensing Prison for a year. His whereabouts between his release and December 1902 are unknown, but in January 1903 he was back in New York City advertising for a partner to put up $500 to help fund another female baseball team. He was using the alias Frank W. Hartright and using 23 Manhattan Avenue as his contact address. In April, agents of the NYSPCC spotted one of Wilson’s ads soliciting young ladies to join a basketball club. The girls were to report to the stage entrance of the Bon Ton Music Hall — a seedy theater located at 112 West 24th Street. Society agents sprang into action, immediately opening another investigation on Wilson that bore fruit in June when Max Bracklow — an employee of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel — claimed that Wilson had defrauded him out of $200 he invested in Wilson’s “woman’s base ball team and vaudeville show.”24 Bracklow reported that he had accompanied Wilson and a group of young women to Peekskill where they had played basketball for a week to get conditioned for the upcoming baseball season. He testified that Wilson’s plan was to hold baseball games in the afternoon and vaudeville performances in the evening.25

Bracklow’s charges of fraud against Wilson paled in comparison to the NYSPCC discovery that Wilson had not only lured underaged girls from their homes to join his entertainment troupe, but that he had also had sexual relations with some of them and shown them pornographic photographs.26 NYSPCC detectives Pisarra and Fogerty gathered enough evidence against Wilson that he agreed to plead guilty to a first offense rather than go to trial. (Conviction on a second offense could have brought a 20-year sentence.) Wilson received a 9-year sentence to Sing Sing that ended up being a life sentence.27 The 1910 federal census indicates that Wilson was a “patient” in Dannemora, New York — location of the State Mental Hospital where state prisoners were sent; he was still there in 1920 and died there on December 7, 1921. He was 69 years old.28

Had Wilson not been the crook he was, he might have made a positive contribution to the history of professional women’s baseball instead of giving it a reputation for debauchery that took decades to overcome. Wilson was a masterful marketer whose hyperbolic flimflammery rivaled that of P.T. Barnum. He knew how to attract crowds — as evidenced by the dozens of hometown newspapers across the country that noted that attendance at Wilson’s games were the largest to date in their locales. Approximately 65,000 individuals paid to watch Wilson’s Young Ladies’ Base Ball Club play its 37 games in 1883.29 His biggest triumph as a baseball manager came in 1890 when 7,000 to 10,000 spectators turned out to see Wilson’s Black Stocking Nine play the Allertons at Monitor Park in Weehawken, New Jersey. Wilson planned the grand event with future Tammany Hall leader Charles Murphy who was a big baseball fan and manager of Monitor Park at the time.30

Wilson’s marketing brilliance was to recognize and leverage the shift in attitudes about women’s physical fitness. Wilson launched his baseball enterprises just as the general public was acknowledging the connection between vigorous outdoor exercise and robust health. His oft-repeated pitch to reporters was that he was not organizing female baseball teams just to make money, but “to popularize open-air exercises among the Women of the land . . . as a Beautifying influence.” He pointed out that the ancient Greeks had “understood the value of open-air Gymnastics, and produced those beautiful and graceful figures which, as shown in their marble representatives handed down to us, the world of today cannot rival.”31

Wilson was drawn to female baseball teams because they provided easy access to young girls, but he also seemed genuinely interested in producing a financially viable entertainment commodity. He invested significant capital in his female baseball teams and military drill companies.32 For his first foray into women’s baseball in New York City, he obtained property at the corner of Madison Avenue and 59th Street and built “Wilson’s Amphitheatre and Ladies’ Athletic Grounds” complete with 400 feet of billboards for advertisers.33 He announced in advertisements:

[M]y object is to start a new thing, to develop women of America. I am going to open here a field for their physical perfection. There is to be base ball, lacrosse, archery, polo, walking, running, velocipede riding and everything. Ponies are now in training. The doctors tell me it will knock seven-eighths of their business sky high.34

The idea of “developing” the women of America was a theme Wilson trumpeted with every new team he established and many young women eagerly joined his baseball teams.

Over the course of his twenty-year involvement with female professional baseball, Wilson gave over 130 teenagers and young women the opportunity to travel the country and play baseball. Unfortunately, Wilson did not recruit highly skilled female baseball players; his focus was on physical beauty and most of his players were “well formed” actresses, former circus performers, and young runaways. He taught them only enough baseball to enable them to navigate on the diamond and make a show of pitching, hitting, and catching.35 His rhetoric about promoting baseball as a “Beautifying influence” for women was bunk. Though a handful of Wilson’s players, like Pearl Emerson and May Lawrence, were genuinely talented players, they were not Wilson’s chief drawing card; he was selling sexual titillation and entertainment novelty.36 The majority of his players saw through his false rhetoric and played only a single season or less, but a handful of them stayed for five seasons or more, sticking with Wilson through thick and thin and testifying on his behalf before numerous judges in courtrooms across the country.37

Sylvester Wilson undoubtedly harmed the reputation of professional women’s baseball teams and of female players in general. During Wilson’s 1891–92 trial for abducting Libbie Sunderland, New York State Assembly representative W. E. McCormick introduced a bill entitled “An Act to Prohibit Female Base-Ball Playing.” Though nothing came of the bill, the fact that a New York politician thought to introduce it in the first place indicates the extent to which Wilson had besmirched the reputation of all female baseball players.38

Fortunately for the future of women’s baseball, there were enough girls and women who continued to play baseball in New York and elsewhere that women were able to keep a foothold in the game. As Wilson headed off to Sing Sing for his first stint, the Young Ladies Base Ball Club of New York began operating. Two years later, its star, the highly talented pitcher, Lizzie Arlington, was wowing crowds and helping to rehabilitate the reputation of women’s professional baseball.39

As Wilson’s sentence dragged on, girls and women engaged in games in Central Park, Rhinebeck, and on schoolyards and college campuses across the state and the nation.40 These girls and women inspired others to play and passed their love of the game on to the generations who followed them. Over a dozen New Yorkers played in the World War II-era All American Girls Base Ball League and groups like the New York Women’s Baseball Association and USA Baseball promote the game for countless New Yorkers today.4142 The future of women in baseball is bright. No thanks to Sylvester Wilson.

DR. DEBRA A. SHATTUCK has been researching women baseball players since 1987. Her area of expertise is the nineteenth century and she recently published a first-of-its-kind history documenting the extent to which girls and women have played baseball from its earliest inception: “Bloomer Girls: Women Baseball Pioneers” (University of Illinois Press, 2017). Deb is a retired Air Force Colonel and a long-time SABR member. She is Provost and Associate Professor of History and Leadership at John Witherspoon College in Rapid City, South Dakota, and, though far from her roots in northern Ohio, is still a proud fan of all things Cleveland.

Notes

1 For details on baseball’s evolution and New Yorkers’ involvement with the emergence of the modern sport, see: John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

2 Correspondence, Harper’s Weekly (November 5, 1859), 707. [Note: Guiwit’s name is misspelled in the article; Census data provides the correct spelling along with his age and occupation.]

3 [No Title], Albany Morning Times (May 16, 1859), 2.

4 [No Title], Troy Daily Times (May 17, 1859), 2.

5 Ibid.

6 Examples: “The Daily Avalanche,” Memphis Daily Avalanche (November 11, 1867), 1; “Local . . . Died of Baseball,” Coldwater Sentinel (November 18, 1867), 3; [No Title], Daily National Intelligencer [D.C.], (November 22, 1867), 2; [No Title], The Indiana Herald (November 27, 1867), 2.

7 “Local,” Coldwater Sentinel (November 22, 1867), 3.

8 Rev. John Todd, Woman’s Rights (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1867), 25.

9 The Vassar teams were the Laurel and Abenakis, organized in Spring 1866 and the Precocious organized in Spring 1867. None of the players on the Precocious club had played the previous year on the Laurel and Abenakis. The Vassariana, Vol. 1, no. 1 (June 27, 1866), 2; Annie Glidden to John Glidden, 20 April 1866; The Transcript, No. 1 (June 1867). Vassar sources are available at the Vassar College Archives. Dozens of newspapers mentioned the girls’ nines in Peterboro, New York. The first reference was contained in a letter written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton on August 1, 1868, and published in her women’s rights newspaper, The Revolution, Vol. II, no. 5, (August 6, 1868), p. 66.

10 Dr. Edward H. Clarke, Sex in Education: Or, A Fair Chance for the Girls (Boston: James R. Osgood and Co., 1873), 42. Clarke’s books went through seventeen editions between 1873 and 1886. See, Patricia A. Vertinsky, The Eternally Wounded Woman: Women, Doctors, and Exercise in the Late Nineteenth Century (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 51.

11 Ibid., 18.

12 Sophia Foster Richardson, “Tendencies in Athletics for Women in Colleges and Universities,” Appletons’ Popular Science Monthly (February 1897), 1-10. Richardson played on Vassar’s baseball teams in the mid- to late-1870s.

13 See Table 1, Women’s Teams of New York.

14 Maud Nelson, whose real name was Clementina Brida, was born circa 1873 in the Austrian Tyrol. She emigrated to the United States with her father and brothers in February 1887. Nelson played for numerous barnstorming teams, including some founded in New York City, beginning in 1892. She went on to a forty-year career in baseball as a player, manager, and team owner. The account of Thompson and Jackson is from: “Female Ball Players: How They Knocked Luke Kenney All Over the Diamond,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (July 23, 1889), 6. The article mentioning the “society buds” in Greenwich is from: “Atlantic Breezes: Echoes From Greenwich,” New York Herald (July 9, 1893), 14. A photo of the Pelham Manor team is available from the town historian of Pelham, New York. See: http://historicpelham.blogspot.com/2010/02/photograph-of-only-known-19th-century.html.

15 “Girls Worth Having: What Muscular Evolution has Done for the Development of the American Young Woman . . .” New York World. Reprinted in: St. Paul Daily Globe (Sepptember 6, 1885), 13.

16 “Girl Base Ball Players: Have a Mighty Struggle With the Fort Hamiltons; and the Men Were Mean Enough to Beat by a Score of No One Knows How Many to One. Some Sliding Done, but Precious Little Catching,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (May 6, 1894), 7; “Carrollton,” Saginaw News (28 June 1892), 6; “A Female Base Ball Club in Danger: Attacked by a Cuban Mob and One of the Players Hurt,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (March 6, 1893), 10; “Female Base Ballists,” Utica Sunday Tribune (June 26, 1892); “Local News Gleanings,” The Denton (Maryland) Journal, (May 20, 1893), 2; “How One of the Female Ball Nine Deserted Husband and Babes — Stuck on Being an Actress — She Tagged the Runner and He Hurt Her Arm,” Quincy (Illinois) Daily Herald (June 8, 1894), 8; the Cincinnati Reds were organized in 1891 by Mark Lally. Numerous articles mention that the team was from New York. Examples: “Diamond Dust,” Wheeling Register (July 28, 1891), 3; “Hard Lines for Female Baseball: The Girl Ball-Players Had to Stop Swing Bats,” (New York) World (April 25, 1892), 1.

17 “Sporting Matters,” Lowell Daily Citizen (March 27, 1879).

18 Wilson and Powell were arrested after players Kitty Byrnes (a.k.a. Gracie Clinton) and Mary Callahan went to their lodgings at Hamilton House and demanded their salaries. The men invited the girls to spend the night and seduced them. Wilson and Powell were arraigned in Police Court on the charges on May 24, 1879 and held on $1,000 bond. The charges were later dropped for lack of evidence and they were released. “Deluded Female Ball-Players,” Chicago Daily Tribune (May 27, 1879), 5; “The Ladies’ Athletic Association: Why the Manager and Treasurer Were Put in Jail Yesterday,” New York Herald (May 25, 1879), 8.

19 See chapter 1 of James William Beul, Mysteries and Miseries of America’s Great Cities: Embracing New York, Washington City, San Francisco, Salt Lake City, and New Orleans (St. Louis & Philadelphia: Historical Publishing Co., 1883).

20 References to each of the aliases: New York Clipper (10 Nov 1883); New Orleans Daily Picayune (May 5, 1886); Brooklyn Daily Eagle (September 8,1889); Brooklyn Daily Eagle (June 3, 1903). The NYSPCC was founded in 1875; within four years, its agents were targeting Wilson. Society reports contain several entries on Wilson. See, for example, Twenty-Second Annual Report, New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, December 31, 1896 (New York: Office of the Society, 1897), 57; Twenty-Ninth Annual Report, New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, December 31, 1903 (Albany: State Legislative Printer, 1904). Report contained in: Documents of the Senate of the State of New York 9.17 (1904): 32-33.

21 Wilson’s 1891 arrest and trial were covered in scores of newspapers across the country and in the annual reports of the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Examples from New York papers: “A Female Base Ball Manager Employed a Fifteen Year Old Girl as a Mascot,” Syracuse Courier (15 Aug 1891), 1; “A Wayward Lass: Abbie Sunderland, of this City, the Cause of a Base Ball Manager’s Arrest. . .” Binghamton Republican (15 Aug 1891), 1; “Christian Wilson, Abductor: Some Account of His Career — Near the End of His Rope,” New York Times (16 Aug 1891), 14; The New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children: Twenty-Fifth Annual Report, December 31, 1899 (New York: Offices of the Society, 1900), 40-41.

22 “A Missing Partner: Lady Baseball Players’ Manager Left With Cash; Levied on Bloomers; Manager Smithson of the Cricket Grounds Determined to Have his Share of the Receipts — Manager Franklin Arrested — His Partner Adams is Missing,” Jersey Journal (31 May 1899), 4.

23 The New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children: Twenty-Fifth Annual Report, December 31, 1899 (New York: Offices of the Society, 1900), 40-41.

24 “A Get-Rich-Quick Scheme? Max Bracklow Says He Dropped $200 in Promoting a Female Base Ball Team,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (June 3, 1903), 8. Another article claimed he invested $500. See: “Woman Ball Team Man Arrested: Sylvester F. Wilson, Man of Many Ventures, Is Charged with Abduction,” New York Evening Telegram (June, 7 1903), 2.

25 Ibid.

26 “Gets Nine Years for Abduction: S.I. Wilson, Promoter of Women’s Baseball Teams, Had Pleaded Guilty to Charge,” New-York Tribune, (August 22, 1903), 11. Details on Wilson’s numerous arrests and trials are available in an unpublished report written about Wilson by the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children for prosecutors at his 1903 trial. The unpublished “Brief for the People” is part of the files of the N.Y. Court of General Sessions for People Against Sylvester F. Wilson, New York City Municipal Archives.

27 NYSPCC Superintendent E. Fellows Jenkins and Agent Vincent Pisarra testified against Wilson at his final trial in June 1903. Pisarra later mentioned his role in apprehending Wilson in the New York Evening Telegram (May 13, 1919).

28 New York State Death Index, #67147.

29 I compiled these statistics from newspaper articles. The total is extrapolated by taking the average number of spectators for the 21 games with reported attendance (37,000 spectators/an average of 1,762 per game) and using that average for the remaining 16 games for which no figures are given.

30 Murphy had been a talented player in his youth and stayed involved with the sport as he worked his way up the ladder in New York City’s political machine; he was unofficial “chief lieutenant” for the eighteenth district when he and Wilson staged the game in Weehawken. For background on Murphy’s association with baseball see Nancy Joan Weiss, Charles Francis Murphy, 1858-1924: Respectability & Responsibility in Tammany Politics (Northampton, MA: Smith College, 1968), 22.

31 Chicago Tribune (30 Mar 1879).

32 Several of Wilson’s baseball troupes traveled with female military drill companies and/or music groups. See, for example, “Freeman in Bondage: The Manager of the Female Base Ball Club Punished as a Vagrant,” New Orleans Daily Picayune, (5 May 1886); “Frolicking Freeman: The Man who was in Galveston with Female Base-ballers ‘Detained’ in New Orleans as a Dangerous Character,” Galveston Daily News, (7 May 1886), 15; Shenandoah Herald [Woodstock, VA] (25 Oct 1889), 3.

33 An advertisement for the grand opening of the grounds appeared in: “Amusements,” New York Herald (12 May 1879). An ad in the New York Herald (14 May 1879) announced that vendors could apply for “refreshment privileges” and “400 feet of Bill Boards.” Thanks to John Thorn for bringing these to my attention.

34 “Red and Blue Legs: A High Old Game of Base Ball by Eighteen Women,” Washington Post (12 May 1879), 1.

35 For an example of a player advertisement see: Pittsburg Dispatch (21 Sep 1889), 3. For details on what Wilson taught the players see: “Girls to Play Ball: A Team Composed of Pittsburg Young Ladies Being Organized; Good Material to Select From; Many of the Girls Enthusiastic Over the Open Air Pastime; Glad to Escape From Indoor Work,” Pittsburg Dispatch (23 Sep 1889), 5.

36 Pearl Emerson and May Lawrence (almost certainly stage names) played on Wilson’s teams from 1883 to 1889. They usually played pitcher, catcher, and first base.

37 Information on player tenure was compiled by studying hundreds of available box scores on Wilson’s teams. Newspaper articles about Wilson’s numerous arrests abound and some mention his players testifying on his behalf. Example: “Winsome Witnesses: The Female Base Ball Club in Court — Sporr Discharged,” Kansas City Star (2 Nov 1885), 5. Even Libbie Sunderland, the young woman Wilson routinely molested testified in court at his trial for abducting her that Wilson had treated her “as a father and furnished her a home.” “Female Baseball Player: A Trial in New-York Discloses Interesting and Shameful Details,” Buffalo Express (13 Oct 1891), 2.

38 McCormick introduced his bill in March 1892. Journal of the Assembly of the State of New York at Their One Hundred and Fifteenth Session (Albany: James B. Lyon, State Printer, 1892): 785. Members of the Assembly seem to have considered the legislation a joke. See proposed amendments for March 25, 1892: Journal of the Assembly of the State of New York at Their One Hundred and Fifteenth Session (Albany: James B. Lyon, State Printer, 1892): 1326. “The Excise Bill: The Assembly Committee Reports A Compromise Bill…” Auburn Bulletin (4 Mar 1892), 1.

39 Information on this team is culled from contemporary newspaper articles. It is quite difficult to distinguish between different teams as many had similar sounding names and newspapers sometimes confused them. It appears that the Young Ladies Base Ball Club of New York may have also been called the New York Stars and may have been renamed the New England Bloomer Girls at some point. Lizzie Arlington joined the team in either 1894 or 1895 and, after a brief stint playing for men’s minor league teams, was still with them as late as 1901. “Lady Ball Players: Hit the Sphere and Run Bases Just Like Real Men; Some Incidents of the Cramer Hill Game,” (Philadelphia) Evening Item (22 Jun 1895); “Did You Ever?” King’s Weekly [Greenville, NC] (26 Jul 1894), 4.

40 “Throngs in Central Park. . . .” New York Herald Tribune (11 Jun 1894), 4. In July, the Rhinebeck Gazette (21 July 1894) informed readers that the local all-female Ostrich Feathers would be playing a match game against the Pond Lillies on July 28. Schoolgirls in Lowville organized the Miss Allen and Mrs. Jones teams in June 1897. “Brief Mention,” (Lowville) Journal & Republican (10 Jun 1897), 5. Students at Vassar College played football, basketball and baseball. Annie E. P. Searing, “Vassar College,” Harper’s Bazaar (30 May 1896): 469.

41 For information on New Yorkers in the All-American Girls Baseball League and on the New York Women’s Baseball Association, see: http://nywomensbaseball.com. USA Baseball hosts a women’s national team. See: http://web.usabaseball.com/womens_national_team.jsp.

42 For information on New Yorkers in the All-American Girls Baseball League and on the New York Women’s Baseball Association, see: http://nywomensbaseball.com. USA Baseball hosts a women’s national team. See: http://web.usabaseball.com/womens_national_team.jsp.