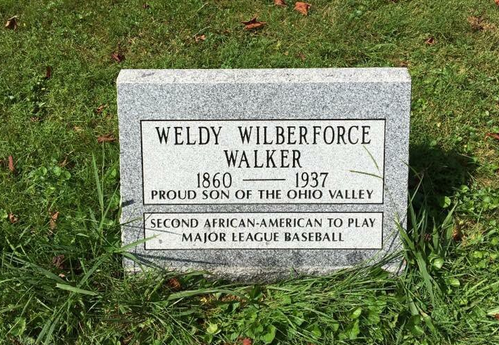

Black baseball pioneer Weldy Walker finally receives a grave marker

The second African-American to play major-league baseball now has a proper grave marker, thanks to the efforts of SABR member Craig Brown and the Negro Leagues Grave Marker Project.

The second African-American to play major-league baseball now has a proper grave marker, thanks to the efforts of SABR member Craig Brown and the Negro Leagues Grave Marker Project.

Weldy Walker played four games for the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884, along with his brother Moses Fleetwood Walker, in the American Association. They were the first two African-Americans to play in the majors during the years before a ban was placed on players of color in baseball.

Brown spearheaded the fundraising effort to raise about $1,400 to purchase the grave marker at Union Cemetery in Steubenville, Ohio, where several members of the Walker family are buried.

“It would be one thing if they were just baseball players, but Weldy and his brother were extraordinary people at the same time,” Brown told the Toledo Blade. “They are some of the earliest civil rights pioneers post-Civil War. They were both very active.”

According to Weldy Walker’s SABR biography, written by John Husman, his baseball career began at Oberlin College in 1881, when he joined his brother Fleet on the school’s first varsity inter-collegiate team in 1881. He then followed his sibling to the University of Michigan and played baseball for two seasons while pursuing his degree in the homeopathic medical school. Fleet moved on to play catcher with the major-league Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884 and, later that summer, Weldy followed his brother home to their native Ohio.

Weldy Walker made his major-league (and also professional baseball) debut on July 15, 1884, just two months after his brother began playing for Toledo. He appeared in four games as an outfielder and hit .286. It was his only major-league experience. He later played briefly in 1885 with Cleveland in the short-lived Western League and in 1887 with Akron and Pittsburgh of the Ohio State League.

Other players of color were also active in the minor leagues at this time, but by the end of the decade, an informal ban had been established throughout the country. As Husman writes, it was Fleet Walker’s appearance for Toledo in an 1883 exhibition game against the National League’s Chicago White Stockings that “marked the beginning of the end of African-American participation in Organized Baseball.” The game of August 10, 1883, played in spite of the protest of the Chicago manager Cap Anson, “brought the issue of racially integrated baseball to the forefront and began an open, blatant, and successful effort to bar black players.” Black players were not allowed to participate in Organized Baseball for more than a half-century, until Jackie Robinson made his debut with the International League’s Montreal Royals in 1946.

Since the Negro Leagues Grave Marker Project was formed in 2003, it has raised funds to mark the final resting places of dozens of black baseball greats like Hall of Famer Frank Grant, historian Sol White, pitcher John Donaldson, and others.

To learn more about or to make a tax-deductible donation to the SABR Negro Leagues Grave Marker Project, click here.

Originally published: September 26, 2016. Last Updated: September 26, 2016.