Chick Stahl: A rainbow in the dark

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the Deadball Era Research Committee newsletter, “The Inside Game,” in November 2013. For more information on the Deadball Era Committee, click here.

By Dennis Auger

The March 1907 suicide of popular Boston player-manager Chick Stahl is a matter shrouded in misunderstanding. More than 50 years after the fact, author Al Stump asserted that Stahl’s death was prompted by the blackmail threats of a designing woman supposedly carrying Stahl’s unborn child. Since then, baseball historians have uncritically accepted the Stump claim. This essay presents an alternative theory, and one, unlike Stump’s, supported by evidence in the historical record. Chick Stahl’s suicide was the end product of longstanding, chronic depression, a thesis that I first offered in Mysteries from Baseball’s Past (McFarland, 2010). The text below provides additional support for that contention and can be viewed as a supplement to my previous commentary in Mysteries.

The March 1907 suicide of popular Boston player-manager Chick Stahl is a matter shrouded in misunderstanding. More than 50 years after the fact, author Al Stump asserted that Stahl’s death was prompted by the blackmail threats of a designing woman supposedly carrying Stahl’s unborn child. Since then, baseball historians have uncritically accepted the Stump claim. This essay presents an alternative theory, and one, unlike Stump’s, supported by evidence in the historical record. Chick Stahl’s suicide was the end product of longstanding, chronic depression, a thesis that I first offered in Mysteries from Baseball’s Past (McFarland, 2010). The text below provides additional support for that contention and can be viewed as a supplement to my previous commentary in Mysteries.

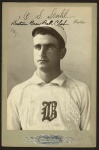

Charles Stahl was born on January 10, 1873 in Avilla, Indiana, but Fort Wayne was considered his hometown. His parents were devout Roman Catholics of German heritage. Chick became a member of the Boston Beaneaters in 1897. How does one assess his major league career (1897-1906)? A perspective can be gained by comparing him to Thurman Munson (1969-1979). Significant parallels exist in terms of length of career, offensive statistics, and defensive abilities. These two Midwesterners were not the greatest ballplayers of their respective eras but they were certainly in the top echelon. Lastly, their untimely deaths cut their careers short and probably prevented them from accumulating the numbers required to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame.

In 1901, Chick jumped to the American League. The Boston Americans franchise was a successful one, winning the World Series in 1903 and repeating as league champions in 1904. The team’s fortunes then took a precipitous fall. The 1906 club was ravaged by poor play and dissension, highlighted when player-manager Jimmy Collins went AWOL. Stahl took over the managerial reins but the team finished with 105 losses.

Two significant events occurred in Stahl’s life in November 1906. Stahl was a practicing Catholic and he met Julia Harmon at a church function. They were married at St. Francis De Sales Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Following the honeymoon, the thirty-three old “benedict” agreed to be Boston’s player-manager. Little Rock, Arkansas was the site of spring training in 1907. As the team moved north, Stahl abruptly resigned as manager on March 25 in Louisville. The Americans arrived at West Baden Springs, Indiana two days later and the Hoosier native agreed to continue as interim manager until a replacement was selected. That evening he wired a telegram to Julia which read, “Cheer up little girl and be happy. I am alright now and able to play the game of my life.”

His activities the next day, March 28, began innocently enough — he had breakfast and checked the playing field conditions. Returning to his suite, Stahl drank four ounces of carbolic acid and suffered an excruciating death. His last words were, “Boys, I couldn’t help it, it drove me to it.” Because the death was ruled a suicide, a Catholic funeral service was prohibited. Fraternal societies performed the funeral rites which were attended by several thousand mourners.

At this point, I digress for a paragraph, but there is a raison d’e?tre. As a member of Notre Dame’s “subway alumni,” I truly appreciated the football team’s renaissance in 2012. An essential component of the season was how linebacker and team captain Manti Te’o dealt with personal tragedy. Then the tragedy saga was exposed as untrue.

In the aftermath, Todd Burlage in Blue & Gold Illustrated took himself and media outlets to task for erroneous journalism and “factual failure.” He pointed out that the reported facts, many of them conflicting, could have been checked but were not, and concluded that the Te’o portrayal was “based on a faulty herd mentality that if it’s in print or on the Internet, it’s gotta be true.” Enthralled by this emotionally powerful story, I, too, failed as a Te’o fact-checker and did not think of questioning the original story’s veracity. It is a journalistic trap one can easily fall into. Why interject this anecdote here? In my opinion, the published word about Stahl’s suicide suffers the same problems as the Te’o debacle. To rectify this, providing historical accuracy regarding the Stahl demise must be the paramount objective.

Why did Stahl commit suicide? The prevalent view is that it was the result of being blackmailed. Several prominent authors have advocated or given credence to this theory, and it has become accepted as fact in much of the national pastime’s literature.

What follows is a chronological presentation of the blackmail story by date of publication. Al Stump was the first writer to promulgate the theory, originally in the May 1959 issue of True Magazine. He repeated it later that year in the September issue of Baseball Digest in an article captioned “Baseball’s Biggest Headache: Dames.” According to Stump, when Stahl was at West Baden, “he had a visitor from his past. She was a doxie he’d known casually and inconclusively in Chicago months earlier. Now claiming pregnancy, she demanded money and marriage — or disclosure and scandal. Stahl’s pleas couldn’t quiet her.” So he committed suicide.

In 1971, Harold Seymour wrote that “there is reason to believe that a woman who asserted she was his pregnant wife hounded Chick Stahl into … committing suicide.” David Quentin Voigt (1983) later reported that “baseball Sadies sometimes blackmailed those who enjoyed their favors.” Stahl was “distraught over fear of exposure” and killed himself.

The next contributor was Glenn Stout who discussed the suicide in an article entitled “The Manager’s End Game” (1986 and 1991). Stout stated that “Chick Stahl was driven to his death by the specter of scandal initiated by a women (sic) who was not Mrs. Stahl. She was a ‘baseball Sadie’ (i.e., a groupie). …While the Americans played in Chicago late in the 1906 season Stahl … had a brief affair with an anonymous woman who is said to have made a habit of sharing her bed with ballplayers … She first contacted Stahl during the Americans’ stay in Little Rock in early March. Her demands were simple: either he would agree to marry her or she would tell the world about the expected child.”

Stout cited Frederick O’Connell, a baseball correspondent in 1907, to support the blackmail story. O’Connell had written that “a great trouble was generally admitted” and “many knew the cause” of the [Stahl] suicide.” Stout also stated that “the basic ingredients of the story are generally accepted. Two of baseball’s most noted historians, Harold Seymour and David Voigt, refer to the sad tale in their multi-volume histories.” In addition, Floyd Conner (2000), Bill James (2001), Derek Gentile (2003), and John Snyder (2006) all reiterated the same story.

Peter Golenbock (2005) quoted Stout as follows: “Seymour and Al Stump wrote a story that he killed himself because of a baseball Annie. Supposedly, he had had a relationship with a woman in Chicago the previous year. What happened is that she got pregnant … she started to blackmail him.” So he killed himself.

Peter Golenbock (2005) quoted Stout as follows: “Seymour and Al Stump wrote a story that he killed himself because of a baseball Annie. Supposedly, he had had a relationship with a woman in Chicago the previous year. What happened is that she got pregnant … she started to blackmail him.” So he killed himself.

What is the purpose of such an extensive listing here? It is to demonstrate the popularity of the blackmail story and to show that it has become ensconced in baseball annals. The other reason is based in scholastic discourse. According to Thomas Aquinas, it is imperative to present an opposing argument clearly and fairly because only in this way can one judge the argument’s merits. As I see no value in misrepresenting the writings of others, I have taken much effort to cite the above authors accurately. Their words will now be examined.

As previously noted, Stump is the original proponent of the blackmail theory, unveiling it 52 years after the event. His Baseball Digest article contained over eighty paragraphs, but devoted less than an entire one to the alleged incident. Stump related the story without providing any documentation or sources. Where did he derive his information about the woman? That she was a doxie? That she lived in Chicago? That she was pregnant? That Stahl knew her casually? That the ballplayer pleaded with her because she threatened blackmail? Stump never identified how, where, and when he obtained such specific information to back up his allegations. In short, he failed to abide by the basic principles of historical research.

Seymour’s “there is reason to believe” certainly does not meet the criteria of proof, either. Researcher Chris Christensen states that the noted historian’s papers at Cornell University “revealed no trace of information concerning Chick Stahl.” As for Voigt’s documentation, he simply refers to Stump’s article. Concerning Stout’s version, it is fair for a reader to ask: From whence do the details come? An expression such as “a great trouble” is open to a plethora of interpretations. Lastly, invoking the undocumented writings of Stump, Seymour, and Voigt and employing the word “supposedly” does not prove the theory in question.

So why has the blackmail story become embedded in baseball’s history? It is because many well respected historians have reported it as fact, the absence of supporting evidence notwithstanding. A well-founded journalistic standard is that two independent sources are required to verify an investigative story prior to publication. The Apostle Paul, well versed in Jewish and Roman law, wrote that “a judicial fact shall be established only on the testimony of two or three witnesses.” Is it not right to ask who are the witnesses or sources behind the blackmail story that make it factual, i.e., an actual occurrence?

In conclusion, as stated in my Mysteries article, “the blackmail proponents fail to provide documentation and identifiable sources confirming the veracity of the theory in question. They have never been able to specify a named or unnamed source” that proves or corroborates even one detail of the alleged blackmail incident. The blackmail allegation resembles a house of cards that collapses under analytical scrutiny.

Based upon my research of the Stahl suicide, I have come to the conclusion that Al Stump is responsible for the blackmail story. He is the source upon whom all the others rely, and the author most often referred to in terms of confirming what happened. The post-Stump writers do not identify any sources substantiating their viewpoint, other than Stump.

So who was Al Stump? I refer readers to William Cobb’s award-winning article “The Georgia Peach: Stumped by the Storyteller” in the 2010 issue of The National Pastime. Cobb concluded that Stump “is a proven liar, proven forger, likely thief and certainly a provocateur who created, fabricated and sensationalized stories of the True Magazine ilk.” Well researched evidence is provided by Cobb for these statements.

As William Cobb’s purpose was to debunk some of Stump’s allegations about Ty Cobb, he did not address Stump’s assertions about the Stahl’s suicide. But given the exposure of Stump’s fabrications about Ty Cobb, one cannot avoid this question: how credible is the Stump blackmail story? Do historians want to rely on an author who offers no documentation and has questionable reliability?

Speaking personally, I was once an adherent of the blackmail story. But the documentation issue, combined with a one-page article written by SABR member Dick Thompson in 1999, changed my mind. Thompson discovered an extensive article on the Stahl suicide which had appeared in the March 30, 1907 edition of the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette. The article headline and sub-headlines read as follows: “Meditated Self-Slaying, Chick Stahl Had Often Talked About Suicide; Base Ball Player Had Entertained Dangerous Ideas About Self- Destruction.”

Stahl had longstanding roots in Fort Wayne and the newspaper account reported that his closest friends were not shocked by his demise. The Journal-Gazette reporter interviewed a city official who had been friends with Stahl since boyhood. The official related that “Chick talked about killing himself several times when he was discouraged about his affairs.” On one occasion, the official heard Stahl say to the barber shaving him, “If you would just push that blade in and cut my head about half off, so I would never feel it, I’d be rid of my troubles.”

According to this lifelong friend, that incident occurred five years previous, “but more than once before that time and more than once afterwards he [Stahl] was heard to say things that indicated a suicidal tendency.” Such suicidal ideation was present throughout adulthood. When he was playing amateur ball (approximate age: 17), Chick “had periods of mental depression and when the future looked dark he used to talk about taking his own life. Sometimes the slightest disappointment would sink him into almost a stupor of depression, and on these occasions his teammates and manager used to fear that he had designs on his own life.”

The Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette account adds other dimensions to this beloved player’s personality profile. Stahl was struggling emotionally with the fact that his best years as a player were behind him and he feared “the down grade” to the minors. Also, “the realization by himself that he could not manage a team preyed on his mind … He had a horror of having to appear before an audience in the role of one who outlived his usefulness.” Even though Stahl often seemed jovial, “there was ever in his ready laughter a sort of half-repressed melancholy … there could be seen something in his demeanor that told that his jollity was forced.”

Besides the Journal-Gazette account, Sporting Life reported that Washington players had observed this same Stahl melancholy in 1906, and this was prior to the alleged September liaison in Chicago. Based on the above symptoms and history, Stahl would clearly be diagnosed with clinical depression.

Attention also needs to be paid to Chick’s religious faith. He was a devout Catholic, a fact attested to by various sources, including Frederick O’Connell who on March 31, 1907 wrote: “Stahl never forgot his religious duties during the baseball season. Only a week ago last Sunday, Stahl did his Easter duty in Little Rock. He never missed mass if it was possible for him to attend.” In Stahl’s day, fulfilling the Easter obligation was a bedrock tenet of Catholicism, on par with keeping the Ten Commandments.

My commentary now enters the theological realm. What if the illicit sexual liaisons are someday proven? Will that negate the view that depression was the cause of the Stahl suicide? My answer is No. In analyzing the question, I would like to incorporate what it was it like to be a practicing Catholic during the two centuries prior to the Second Vatican Council of 1962-1965. One defining trait of Catholic morality was that it was permeated by Jansenism which was an ultra-rigid spirituality, especially ingrained in those of Irish, French, and German heritage. Special vigilance had to be taken concerning sexual sins. For example, taking pleasure in a sexual thought was a mortal sin that would result in eternal damnation if not confessed and repented.

To explore this, an appeal will be made to an unorthodox and lapsed Catholic theologian — George Carlin! In his routine “I Used to be Irish Catholic/The Confessional,” the comedian highlights how easy it is to commit a mortal sin by giving two examples. First, it all comes down to intention, “so if your intention is to go to 42nd Street and commit a mortal sin, save your carfare, you already did it!” Thereafter, Carlin focuses on sexual morality. Concerning foreplay (edited), “it was a sin to want to feel up Ellen, a sin to plan it, a sin to think of a place, a sin to take her to the place, a sin to try to, and a sin to do it. Six sins in one feel!”

If you are over age 60 and raised Catholic, you might be able to resonate with this. Despite being humorous, Carlin offers a valuable insight into the mores of a past era. The avoidance of committing a mortal sin was no easy task for any person, but for a man like Stahl suffering from depression, the burden would be even greater. It cannot be known if Chick was encumbered by the weight of Jansenistic morality. However, if he was and if the allegations about promiscuity are true, the guilt that he suffered would be one more contributing factor contributing to his self-destruction.

There is another area to reflect upon when examining Stahl’s faith and Catholic teaching. The Church imposed a strict moral code, and not only in sexual matters. It also emphasized that God’s mercy was infinite. That being so, what was the unforgiveable sin? It was suicide, viewed as the irrevocable rejection of God, the source of all life and the dispenser of forgiveness to all who seek it. The Church condemnation of suicide would have been well understood by a practicing Catholic like Chick Stahl. Thus, only something as debilitating as severe mental depression was likely capable of reducing Stahl to the state where he would commit Catholicism’s unpardonable sin and thereby place his immortal soul in peril.

Based on superficial portrayals, Stahl can be seen as a narcissistic womanizer. But what kind of character did he really possess? Chick was frugal and a wise investor in real estate. He was generous to his family, purchasing a home for his mother and helping a brother start a business. As a ballplayer, he refrained from “rowdyism.” On one occasion, he and teammate Ted “Parson” Lewis escorted an umpire off the field when the crowd threatened harm.

At a time when racism was prevalent, Stahl appeared in a photo with young black children in Deep South Macon, Georgia. Chick’s concern for others was exemplified when he discussed his managerial stress, “Releasing players grated on my nerves … it made me sick at heart.” His teammates clarify the profile. Cy Young reflected that “players may come and go, but there are few Chick Stahls.” Lou Criger gave this testimonial: “He was the squarest man I ever knew. He had only one fault — he was too generous. He was often bunkoed because he believed in the goodness of all mankind.” At the Stahl funeral, Congressman James Robinson offered the eulogy and said that “our brother loved his fellow-men and believed that the pinnacle of ambition was reached when he did his duty to all. … He squared his conduct to the Golden Rule.”

A researcher, including myself, must be willing to incorporate new discoveries and insights into any analysis. This can result in modifying or even changing one’s conclusion. Based on the evidence, sources, and documentation available, my present view is that the primary and underlying reason for Stahl’s suicide was his lifelong battle with depression. Managerial stress, fear of declining athletic ability, the alleged sexual liaison, and the perfectionism arising from his religious belief and accompanying guilt would all be contributing factors exacerbating his depression resulting in his act of desperation. In conclusion, the lyrics of heavy metal vocalist Ronnie Dio seem apt:

Do your demons ever let you go, do they hide deep inside

No sign of the morning coming, no sign of the day

You have been left on your own like a rainbow in the dark

You are a rainbow in the dark.

Charles Stahl’s goodness, virtues, faith, and talents are symbolized by the rainbow while the darkness represents his depression and internal turmoil. On March 28, 1907, the beauty of the rainbow was eclipsed by the darkness.

Deadball Era Committee member DENNIS AUGER of Uxbridge, Massachusetts is also the author of the BioProject profile of Chick Stahl.

Originally published: November 12, 2013. Last Updated: November 12, 2013.