Leg Men: Career Pinch-Runners in Major-League Baseball

This article was written by Clifford Blau

This article was published in Summer 2009 Baseball Research Journal

In 1974, the Oakland Athletics signed track star Herb Washington as a “designated runner,” despite his having had very little baseball experience. Keeping on the roster a player whose only purpose was to run was a new idea, but there have been many other real baseball players whose main purpose it was to pinch-run. The first was Wilson Collins in 1913 with the Boston Braves. This article gives the stories of all baseball players who did nothing but pinch-run in at least half of their career major-league games (minimum five appearances). It will attempt to show how they came to be used in that capacity. The players are presented in order of their initial major-league appearance.

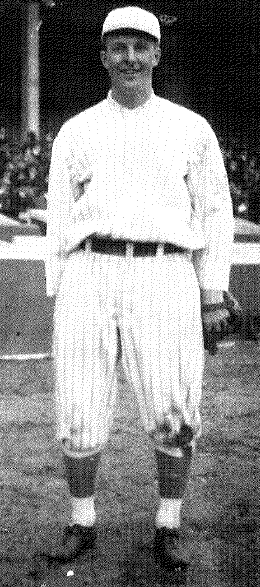

Charles William R. (Sandy) Piez was the first player to spend most of his major-league career as a pinch-runner. Sandy was the first of four sons born to German immigrants, Anton and Huldah (Hormick) Piez. His birth date has usually been reported as October 13, 1892. However, with the assistance of Richard Malatzky, I discovered that he was actually born on that date in 1888 in New York City. A couple of years later, Anton moved the family to Erie, Pennsylvania, where Charles grew up. He began his professional career while at college in 1910, at first playing under an assumed name, later under his own. In his fourth year in pro ball, he attracted the attention of several major-league teams by stealing 72 bases in the Virginia League. The Giants purchased his contract midseason. John McGraw looked him over during spring training in 1914 and, rather than farm him out to a higher minor league, decided Piez could help the Giants by pinch-running for their slow-footed catchers. McGraw had used several players in that role the previous year, including Claude Cooper, Eddie Grant, and Jim Thorpe. Sandy, also nicknamed Sweet, did nothing but pinch-run until his twelfth appearance when, after running for Chief Meyers, he stayed in the game in right field for two innings, not getting to bat. His next appearance in the field came on September 16. With the Giants leading the Reds 8-0, he replaced George Burns in left and got his first at-bat. Finally, on the last day of the season, Piez started both games of a doubleheader against the Phillies, playing center field in the first game and left in the second. He hit two singles and a triple to finish his major-league career with a .625 slugging average. As a pinch-runner, he scored 8 runs in 33 games, stealing 4 bases. The following year, the Giants sent him to Rochester in the International League. Sandy managed to steal only 17 bases in 117 games in 1915 and, when offered the head coach position with the Rutgers baseball team the following year, he decided to retire as a player. Piez spent two years coaching at Rutgers, where his team went only 6-11. After his coaching career, he tried his hand at several business ventures. His final job was as a salesman for a gas-heater company. The end came unexpectedly soon for Sandy. On December 29, 1930, he was in a car driven by his brother-in-law. The car slid off an icy bridge in Atlantic City and into the ocean; while the driver escaped, Sandy drowned, leaving behind his wife Helen and a 15-year-old son, Charles Jr.

Charles William R. (Sandy) Piez was the first player to spend most of his major-league career as a pinch-runner. Sandy was the first of four sons born to German immigrants, Anton and Huldah (Hormick) Piez. His birth date has usually been reported as October 13, 1892. However, with the assistance of Richard Malatzky, I discovered that he was actually born on that date in 1888 in New York City. A couple of years later, Anton moved the family to Erie, Pennsylvania, where Charles grew up. He began his professional career while at college in 1910, at first playing under an assumed name, later under his own. In his fourth year in pro ball, he attracted the attention of several major-league teams by stealing 72 bases in the Virginia League. The Giants purchased his contract midseason. John McGraw looked him over during spring training in 1914 and, rather than farm him out to a higher minor league, decided Piez could help the Giants by pinch-running for their slow-footed catchers. McGraw had used several players in that role the previous year, including Claude Cooper, Eddie Grant, and Jim Thorpe. Sandy, also nicknamed Sweet, did nothing but pinch-run until his twelfth appearance when, after running for Chief Meyers, he stayed in the game in right field for two innings, not getting to bat. His next appearance in the field came on September 16. With the Giants leading the Reds 8-0, he replaced George Burns in left and got his first at-bat. Finally, on the last day of the season, Piez started both games of a doubleheader against the Phillies, playing center field in the first game and left in the second. He hit two singles and a triple to finish his major-league career with a .625 slugging average. As a pinch-runner, he scored 8 runs in 33 games, stealing 4 bases. The following year, the Giants sent him to Rochester in the International League. Sandy managed to steal only 17 bases in 117 games in 1915 and, when offered the head coach position with the Rutgers baseball team the following year, he decided to retire as a player. Piez spent two years coaching at Rutgers, where his team went only 6-11. After his coaching career, he tried his hand at several business ventures. His final job was as a salesman for a gas-heater company. The end came unexpectedly soon for Sandy. On December 29, 1930, he was in a car driven by his brother-in-law. The car slid off an icy bridge in Atlantic City and into the ocean; while the driver escaped, Sandy drowned, leaving behind his wife Helen and a 15-year-old son, Charles Jr.

Edward Francis Hock was born March 27, 1899, in Franklin Furnace, Ohio. His father, Adam Hock, the son of Prussian immigrants, was a farmer, while his mother Mary Catherine (Compliment) Hock raised Eddie and his three younger siblings. When the United States entered World War I, Eddie volunteered for the navy. Hock returned home after the war and played baseball on weekends in an independent league. He attracted the attention of the st. Louis Cardinals, who gave him a brief tryout during July 1920. Eddie got into only one game and soon returned home. He began his professional baseball career in earnest the next year, playing for Richmond in the Virginia League. At the close of the season, he was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds, who assigned him to Atlanta in the Southern League for 1922. At the start of the 1923 season, the Reds kept him until early May, using him twice as a pinch-runner before shipping him to Oklahoma City in the Western League, where he would play most of the next four seasons. Hock started the 1924 season with Cincinnati again, this time staying with them until mid-June, pinch-running 10 times in 16 appearances and scoring 5 times in that capacity. When they tried to send him to the minors, he failed to clear waivers and the Pittsburgh Pirates claimed him. Ironically, the Bucs immediately sent him to Oklahoma City in partial payment for Emil Yde. Hock had been playing each of the outfield positions to this point, but in 1925 Oklahoma City converted him to shortstop, and he later moved to third. Eddie was now at his peak, leading the Western League in 1925 with 53 stolen bases, and scoring 127 runs in 1926. However, he never again played in the major leagues. He became a playing manager in 1935 and continued in this role through 1942, winning three pennants. Hock spent 22 years in the minor leagues, finishing third all-time in runs and hits, and first in singles. He stole 486 bases in his career. Eddie lived with his wife, Philomena, and two sons, Joe and Fred, in Portsmouth, Ohio. After a protracted illness, he was found drowned in the Ohio River on November 21, 1963, a suicide.

Edward Francis Hock was born March 27, 1899, in Franklin Furnace, Ohio. His father, Adam Hock, the son of Prussian immigrants, was a farmer, while his mother Mary Catherine (Compliment) Hock raised Eddie and his three younger siblings. When the United States entered World War I, Eddie volunteered for the navy. Hock returned home after the war and played baseball on weekends in an independent league. He attracted the attention of the st. Louis Cardinals, who gave him a brief tryout during July 1920. Eddie got into only one game and soon returned home. He began his professional baseball career in earnest the next year, playing for Richmond in the Virginia League. At the close of the season, he was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds, who assigned him to Atlanta in the Southern League for 1922. At the start of the 1923 season, the Reds kept him until early May, using him twice as a pinch-runner before shipping him to Oklahoma City in the Western League, where he would play most of the next four seasons. Hock started the 1924 season with Cincinnati again, this time staying with them until mid-June, pinch-running 10 times in 16 appearances and scoring 5 times in that capacity. When they tried to send him to the minors, he failed to clear waivers and the Pittsburgh Pirates claimed him. Ironically, the Bucs immediately sent him to Oklahoma City in partial payment for Emil Yde. Hock had been playing each of the outfield positions to this point, but in 1925 Oklahoma City converted him to shortstop, and he later moved to third. Eddie was now at his peak, leading the Western League in 1925 with 53 stolen bases, and scoring 127 runs in 1926. However, he never again played in the major leagues. He became a playing manager in 1935 and continued in this role through 1942, winning three pennants. Hock spent 22 years in the minor leagues, finishing third all-time in runs and hits, and first in singles. He stole 486 bases in his career. Eddie lived with his wife, Philomena, and two sons, Joe and Fred, in Portsmouth, Ohio. After a protracted illness, he was found drowned in the Ohio River on November 21, 1963, a suicide.

Horace l. (Pip) Koehler was born January 16, 1902, in Gilbert, Pennsylvania, the third of four children of Franklin and Ida Koehler. He went to college at Penn State, where he played baseball under Hugo Bezdek, former Pittsburgh Pirates manager. Koehler also captained the basketball squad for two years. After graduating in 1923, he taught physical education at Windher High School in Wilkes-Barre for two years while playing semipro ball. The New York Giants brought him to spring training in 1925, where he made a good impression on John McGraw. Koehler was with the Giants briefly after the season started, getting in one game as a pinch-runner before being optioned to Reading in the International League. The Giants recalled him in mid-August, and he made 11 more appearances with them, 9 as a pinch-runner. Following the season, the Giants sent him to Toledo to help complete a deal for Earl Webb. While most players would have been disappointed, Pip was glad for the move because he didn’t feel he was good enough to play in the majors. He spent the next eight seasons in the American Association, putting up good but not great numbers. Although he had good speed, he wasn’t a big base stealer. His top figure was 20 in 1926; he was also caught stealing 13 times that year. In the winters, Pip played and coached professional basketball from 1927 to 1939 in various cities and leagues; at 5-foot-10, he was big enough to play center in those days. On the baseball field, he split his time between the outfield and infield, primarily third base. He married Corinne Ann Slater in 1929. In 1935, he became a playing manager in the Yankees organization. After he was released by the Yankees in 1940, he found a job managing Tacoma in the Western International League. He finished out his playing career in 1942 with Tacoma. In 1947, he was hired as manager of the Ogden Reds in the Pioneer League. During the following season, with the Reds in last place, he was “reassigned” to a scouting position in the Pacific Northwest region with Cincinnati. In the early 1950s, he left baseball. When Tacoma was in need of a new business manager in 1963, general manager Rosy Ryan, a former teammate of Koehler’s in Toledo, hired him. Koehler worked for the club for more than a decade. In December 1986, he died at home following a heart attack.

Herman Layne was born February 13, 1901, to John G. Layne, a coal miner, and Lula Riggs Layne in New Haven, West Virginia. Apart from his baseball career, he lived there his whole life. He had two sisters and two brothers, including a twin, Harry, who also had a 13-year professional baseball career. After attending West Virginia University, Herman joined Bristol of the Appalachian League in 1922. He starred there with a league-leading .354 batting average and his contract was purchased by the Detroit Tigers. The Tigers farmed him out, and he advanced the next two years to the Sally and International Leagues. After he led the International League with 16 triples in 1926, Toronto traded him to the Pittsburgh Pirates for $30,000 and two players. Pittsburgh expected Layne to win their left-field job in 1927. However, he was beaten out in spring training by Lloyd Waner. Layne appeared in just 11 games for the Bucs, 8 as a pinch-runner, before being farmed out to Indianapolis in the American Association in early June. This must have been very disappointing to him, but he got a measure of revenge on June 30. In an exhibition game against the Pirates, Layne hit two homers to lead the Indians to victory. Following the 1929 season, he was traded to Louisville for Eddie Sicking. In his first season with Louisville, he led the American Association in triples and stolen bases. He spent three and a half seasons with Louisville. Layne returned to Indianapolis in 1933, and he finished his career in 1934 with Charleston, West Virginia, in the Middle Atlantic League. Layne’s career batting average was .327, and he played for five pennant-winning teams in his 13·year career. After his retirement from baseball, Herman returned to New Haven, where he had a long and successful career in business. Herman Layne passed away on August 27, 1973 of a heart attack.

Success came quickly but proved fleeting for Dinny McNamara. Tragedy was longer lasting. Born John Raymond McNamara on September 16, 1905, in Lexington, Massachusetts, he was the seventh of ten children born to Dennis and Katherine (Lynch) McNamara, three of whom died before their first birthday. Nicknamed Dinny after his father, John was an all-around sports star at Lexington High School and then went on to attend Boston College. There he played center field on the baseball team and fullback for the football team for four years. Following graduation, he signed a contract with the Boston Braves and in early July made his debut as a pinch-runner, scoring a run. In fact, Dinny would pinch-run seven times in his first eight days with the Braves. After going 0 for 9 in three starts, McNamara was optioned to Providence of the Eastern League, where he finished the season. That fall, he started a job as an assistant college football coach at Fordham. When the 1928 season began, McNamara was back with the Braves but again saw limited action, pinch-running six times and making three other appearances before being returned to Providence at the end of May. Although he fielded well for Providence, his hitting was weak and he could only manage a .266 slugging average in 320 at-bats. Dinny gave up on baseball and concentrated on coaching. After five more years at Fordham, he returned to Boston College in 1934 as assistant football coach and freshman baseball coach. The following year, he was named head football coach. However, an automobile accident two years earlier had left him with emotional problems, and the strain of being head coach was too much for him. With a 3-1 record, he resigned. A lifelong bachelor, he lived out his days in Lexington, apparently never working again. A second automobile accident put an end to his life when he was hit while walking near his home in December 1963.

Robert Wayne Kahle was born on November 23, 1915, in New Castle, Indiana. He was the second son of Edward and Clara Kahle. Following high school, Bob Kahle was discovered playing semipro ball and given a tryout with the Indianapolis club of the American Association. The club’s manager, Red Killefer, signed him and sent him to the lower minors for seasoning. An infielder, Kahle spent three years in the lower minors before getting his shot with Indianapolis. He did well enough there in 1937 to be drafted by the Boston Bees. However, a sore arm hindered his chance to become a regular there. In almost three months with the National League club, Bob got into just eight games, five as a pinch-runner while pinch-hitting three times. Then Boston optioned him to Hartford in the Eastern League. A shooting pain every time he swung the bat or threw the ball limited him to 10 games before he asked to be put on the voluntarily retired list (there being no disabled list then) for the rest of the season. At the end of spring training in 1939, the Bees sold him conditionally to the Yankees’ farm team in Newark. After a month’s trial, they decided not to keep him, and Boston turned around and sold his contract to Hollywood of the Pacific Coast League for $7,500. Killefer was the manager of the Stars, and Kahle settled down as the regular third baseman there for the next five seasons, winning the team MVP award in 1940. Another conditional sale followed that season, this time to the Philadelphia Athletics. Again, the deal wasn’t completed as Connie Mack decided Kahle wasn’t worth the $15,000 price. Kahle’s 29-game hitting streak early in 1941 may have caused Connie to regret his decision. After the 1942 season, Kahle enlisted in the navy. He never saw action, though, except on the baseball field, as he was stationed at various Pacific Coast bases. Returning to the Stars in 1946, he found his third-base spot occupied by Hollywood’s player-manager Buck Fausett. Bob was soon traded to Portland for pitcher Paul Gregory. He was the Beavers’ regular third baseman that year, but early in 1947 he was sent to the Southern Association, where he closed out his playing career with Little Rock. Kahle returned to Hollywood, where he worked as a painter for Burbank Studios for 33 years. Bob maintained an interest in baseball, organizing the Little League in the Westchester section of Los Angeles. Dying of lung cancer on December 16, 1988, Bob left behind his widow Evelyn, three sons, and nine grandchildren.

Patrick Nicholas Capri was born November 27, 1918, in New York City. Pat went to New Utrecht High School and attended Brooklyn College for two years before signing a contract with the St. Louis Cardinals organization in 1938. He worked his way through their enormous farm system, spending two years with Fostoria in the Ohio State League and then playing for Williamson in the Mountain States League in 1940 and Asheville in the Piedmont League in 1941. He led the latter two leagues in double plays by second basemen and made the league all-star team in 1940 while knocking in lOS runs and scoring 98. He was on the roster of Springfield in 1942 when he suffered a knee injury. It was severe enough to keep him out of military service, and he was placed on the voluntarily retired list. That December, he married Rita Petrizzo. In 1944, he was reactivated and started the season with the Columbus Red Birds, who soon released him. He signed as a free agent with Newark, which also released him. However, the Boston Braves, fearing that regular second baseman Connie Ryan would be called up for military service, signed Capri as insurance. As it worked out, when Ryan reported to the navy in late July, the Braves made other arrangements for a new second baseman, and Capri was released in early August. He got into seven games with Boston; only in the last one did he do anything but pinch-run. Capri quickly found another spot owing to the manpower shortage; he signed with Indianapolis. Soon after he joined the Indians, though, he suffered a broken nose and missed two weeks. He closed out the season with Indianapolis, playing 20 games with a .318 batting average. However, he left baseball for good after that, working as a self-employed paperhanger. Pat lived in Brooklyn until his death in 1986.

Some pinch-runners were accepted by their teammates; others were thought to be a waste of a roster spot. Only Joe Tepsic, though, was accused of costing his team a pennant. Joseph John Tepsic was born September 18, 1923, in Slovan, Pennsylvania. After graduating Union High School in Burgettstown, Pennsylvania, he enrolled at Waynesboro College. When America entered World War II, he enlisted with the Marines and was bayoneted in the left shoulder by a Japanese soldier in the battle of Guadalcanal. It took him two years to recuperate; after he did, he enrolled in Pennsylvania State University, where he starred on the baseball team and the football team, besides running the hundred-yard dash for the track team. Following his second spring with the baseball team in 1946, he signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers for an estimated bonus of $17,000. It was the highest bonus the Dodgers had ever given. Part of his agreement with Brooklyn was that he would be kept on the Dodgers the remainder of the season. Due to his inexperience, however, Joe was used sparingly, appearing in just 15 games, 10 of them as a pinch-runner. With the team in a tight pennant race with the Cardinals, general manager Branch Rickey offered Tepsic a reported $1,500 to accept assignment to the minors, but he stubbornly insisted on continuing to warm the Dodgers’ bench, feeling he was better than most of the players on the team. Rickey had hoped to recall veteran Chet Ross. The Cardinals and Dodgers finished the regular season tied, and St. Louis won the playoff for the league title. Many Dodgers felt that Ross could have helped them win at least one extra game down the stretch and blamed their loss on Tepsic. They voted Joe just a one-eighth share of their second-place bonus money. In 1947, the Dodgers were no longer restricted from optioning Tepsic to the minors but when they did so, he indignantly said he would quit before going down. He did in fact go home for two weeks before agreeing to report to St. Paul. His attitude continued to be a problem; despite a .302 batting average, he was demoted to Fort Worth in the Texas League “to promote harmony on the team.” Playing right field, Tepsic made a good impression in the Texas League with his speed, stealing 14 bases in his first 31 games before tailing off. However, the Dodgers sent him outright to Fort Worth after the season. He went to spring training with the Montreal Royals in 1948. He stayed with the Royals briefly; his only appearance with them was as a pinch-runner. When they assigned his contract to Nashua, Joe once again threatened to quit. As a compromise, he was sent to Lancaster in the Interstate League instead. He spent the next few years drifting around the minors. In 1952, Joe realized he wasn’t going to make it in baseball and left the game. He returned home, where he owned and operated a small grocery store with a lunch counter, Village Dairy Store. He retired to Tyrone, Pennsylvania and died February 23, 2009.

Jack Dempsey Cassini‘s chance of becoming a major-league star ended almost before it started. He was born October 26, 1919, the third of five children born to O. J. and Ida (Sprague) Cassini. His younger brother Eddie would grow up to be a minor-league umpire. At the age of 20, Jack began his professional career by tearing apart the Ohio State League. Playing 99 games for Tiffin, he compiled a .396 batting average while scoring 118 runs and had a league-leading 51 steals. Following the season, his contract was acquired by the Cincinnati Reds organization, which assigned him to Ogden in the Pioneer League. He led that league in steals in 1941 but spent the next four years in the army. After the war, the now 26-year-old Cassini was assigned to Syracuse in the International League. After a slow start there, he was sent down to the Texas League, where he finally got his timing back while splitting his time between second, third, and shortstop. When Reds manager Johnny Neun asked him during spring training in 1947 which was his best position, Cassini replied that Bill McKechnie thought it was third, Jewel Ens believed it was second, and club president Warren Giles said he should look for a front-office job. The Reds’ manager didn’t appreciate that bit of humor and released Cassini. Jack went back to the Texas League, which he led in runs and stolen bases. During the season, he won a race against Joe Tepsic to determine who was the fastest man in the league. Tulsa, which had given Cassini a conditional $750 signing bonus the year before, now sold his contract to Indianapolis in the American Association for $6,500. After he led the American Association in steals in 1948, the Pittsburgh Pirates purchased his contract. Jack was a candidate for the third-base job but in his month with the club he got into only eight games, all as a pinch-runner. He scored three times, including the only run on opening day. Then he went back to the American Association. Following the 1949 season, he was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers in a deal for Danny O’Connell. Jack spent four years playing for the Dodgers’ farm club at St. Paul, leading the American Association twice in steals, giving him six league titles for his career. He made the all-star team in 1952 and 1953, making it five times he was so honored in Organized Baseball. Then he was traded to Montreal, where he spent one season. After the 1954 season he was obtained by Memphis of the Southern League to be their manager. Jack played second base for the Chicks and had them a game and a half out of first on August 2 when he was hit in the face with a pitch. He suffered a broken cheekbone and blurred vision. This put him out of action for the remainder of the season and effectively ended his playing career. He spent more than twenty years after that as a scout and minor-league manager. He retired to Arizona and died September 20, 2010.

Howard Edward Phillips was born July 8, 1931, in St. Louis, Missouri. After graduating from Hannibal High School in 1949, where he earned letters in baseball, basketball, football, and track, he signed a contract with the St. Louis Cardinals organization. Eddie had a fine season in 1950 with West Frankfort in the Mississippi-Ohio Valley League, scoring 119 runs in 117 games and stealing 36 bases. Promoted to the Western Association in 1951, he led the league in triples while stealing 28 bases for st. Joseph. However, he would never again steal more than eight bases in a season. Phillips advanced to the Western League in 1952 and led it in batting average. A .306 batting average in the Texas League the next year, despite an ankle injury, led to his promotion to the Cardinals in September. Although he was able to play both infield and outfield, Eddie got into only nine games with st. Louis, all as a pinch-runner, scoring four times. Phillips started 1954 with Houston before being promoted to Columbus in the American Association. He would spend the next five seasons in Class AAA on six different teams. He also played in Panama for three winters, helping Carta Vieja to the pennant in the 1954-55 season. In March 1959, he married Joyce Ann Easley. After 1960, his playing career came to an end. He worked for the American Cyanamid Chemical Company for twenty-five years. He retired to Hannibal, Missouri, and died September 9, 2010.

The bonus rules of 1946-50 and 1953-57 led to a lot of young players sitting on major-league benches rather than developing in the minors. Since they weren’t ready to do anything else at that level, many were used extensively as pinch-runners. Some, like Al Kaline, went on to have great careers. Others, like Tommy Carroll, never achieved much else in baseball. Born September 17, 1936, in New York City, Tommy starred both athletically and scholastically at Bishop Loughlin Memorial High School. He then went to Notre Dame. After compiling a .550 batting average as a freshman and playing semipro ball in the summer, he was highly sought by professional teams. The Yankees beat out a dozen others, signing Carroll to a bonus estimated at anywhere from $35,000 to $60,000. Due to his bonus, he had to remain on the Yankees’ roster for two years. In those seasons, he got into 50 games, pinch-running in 33 of them. He also pinch-ran twice in the 1955 World Series, which he called the greatest thrill of his career. At 6-foot-3, he was quite tall for a shortstop, and the Yankees tried him at third base in 1956. Following his bonus stint, the Yankees optioned him to Richmond for 1957, where he hit with some power but managed only a .213 batting average. He raised that to .283 in 1958, splitting the season between New Orleans and Denver. After that season, he did a six-month stretch in the army. For 1959, the Yankees sent him to Kansas City, but the now 22-year-old saw little action there and was sent down to the minors. Although he tried playing winter ball in Venezuela that year to help his chances of progressing, Tommy never returned to the majors. After playing a few more years, he left baseball and launched a long career in the State Department, serving as a diplomat in several countries in South America.

Mack Edwin Burk was born April 21, 1935, in Nacogdoches, Texas. Like Tommy Carroll, he was a bonus player, condemned to sit on a bench for two years. In Stephen Austin High School in Houston, he was an infielder. He got a basketball scholarship to the University of Texas in Austin, where he also caught for the baseball team. In his first start for the basketball team, he suffered a broken collarbone, which sidelined him the rest of the school year. He got back into action in the summer, playing for the Mechanics’ Uniform Supply team in the American Baseball Congress and helping them win the national championship with a .420 batting average. Several major-league teams recruited him after that, and he signed with the Phillies for an estimated $40,000 in August 1955. Burk reported to the club in 1956. Philadelphia signed him as a catcher, but he got into only one game in the field; he also got to the plate just once, rifling a single off Joe Nuxhall. His other 13 appearances were as a pinch-runner. Early in the 1957 season, Burk was drafted into the army, serving a six-month tour of duty. Following his release, he played ball in Panama. The bonus rule was revoked after the 1957 season, so Philadelphia was able to option Burk to the minors. He spent most of the 1958 season with Williamsport in the Eastern League. The Phillies did recall him briefly during the summer and used him once as a pinch-hitter. In 1959, he started out in the Eastern League, but after going 11 for 14 with three home runs over the Memorial Day weekend he earned a promotion to Buffalo in the International League. But the next year Mack was in the Sally League and then called it a career. After baseball, he worked in electrical-supplies sales. As of 2009, he lived in Houston.

Don Eaddy escaped the bonus-rule trap but couldn’t escape the long arm of Uncle Sam. Born February 16, 1934, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Eaddy was a three-sport star at the University of Michigan. Playing under former major-leaguer Ray Fisher, he found baseball to be his best game; he was all-conference four times, making the All-America team as a senior third baseman. He led the Big Ten in stolen bases his senior year. After graduating with a bachelor-of-science degree, Eaddy was recruited by several teams. Not wanting to sit on a bench for two years as a bonus player but also hoping to get a shot in the big leagues quickly, Eaddy accepted an offer from the Chicago Cubs for a major-league contract at less than the bonus limit. He began his professional career as a shortstop with Des Moines in the Western League; in his first game he started a triple play. After a few games, he was sent to the Three-I League, where he finished the season with a .304 batting average. After getting a look in center field in spring training with the Cubs, Eaddy was back with Des Moines to start 1956. Don was carrying a .390 batting average after 11 games when he was called up by the air force for active duty. He spent the balance of 1956 and the next two years in the service. When he returned to baseball in 1959, Chicago was able to keep him on the roster as a twenty-sixth man, due to his status as a veteran. However, not long after cutdown day, the Cubs sent him down to the Eastern League. He soon earned a promotion to Fort Worth and in late July returned to Chicago for the balance of the season. Unfortunately, he didn’t get to play much in either stint with the Cubs. Eaddy was used in just 15 games, 14 of them as a pinch-runner. Out of options, he was outrighted to Fort Worth after the season. He also went to Cuba in the winter, leading the league in walks and helping Cienfuegos win the Caribbean Series. Eaddy continued to play in the Cubs organization for five more years; he never stole more than nine bases in a season. In the winter of 1963-64, he helped Cinco Estrellas win the International Series. His .347 batting average in Nicaragua helped convince the Cubs to give him another look in 1964. They listed him as a candidate for the second-base job left vacant by Ken Hubbs’s death, although he had played very little there, being mainly a third baseman. Ultimately, he didn’t play there much in spring training either, mainly working at shortstop. He went back to the minors, where he closed out his career as a utility player for Salt Lake City. Following baseball, Don owned several Burger King franchises. In 1996, he was elected to the Grand Rapids Sports Hall of Fame. He died of cancer on July 8, 2008. One of four children, Don Eaddy was survived by his wife, Christine.

Roy Gleason was another player whose career was interrupted by military service. The only person to serve in Vietnam after playing Major League Baseball, he suffered serious battIe wounds and never made it back to the big leagues. Roy William Gleason was born April 9, 1943, in Melrose Park, Illinois. A star outfielder and pitcher at Garden Grove High School in California, he signed with the Dodgers in June 1961 for an amount reported as being anywhere from $55,000 to $108,000. They envisioned him, at 6-foot-5 inches and 227 pounds, as another Frank Howard but with speed. (He ran the 100-yard dash in 9.7 seconds.) A right-handed hitter in high school, he was taught by the Dodgers to switch-hit in the Arizona Instructional League. After looking him over in spring training in 1962, Pete Reiser said he “has the size, desire, speed, and arm to become a great player.” As it turned out, the one thing he lacked was the ability to make contact. In the California League that year, he struck out 214 times in 448 at-bats. For his career, he would strike out an average of .48 times per at-bat. He did cut down his strikeouts some in the Northwest League in 1963, and in September he was called up to Los Angeles. Gleason appeared in seven games as a pinch-runner and one as a pinch-hitter, smacking a double. Roy never achieved the greatness predicted for him; those eight games were the extent of his major-league career. By 1965 the Dodgers were losing patience with him; he had been removed from the 40-man roster and, after a horrible start in the Northwest League, some consideration was given to converting him into a pitcher. He made a few appearances on the mound, but his arm proved to be as wild as his swing. In 19 career innings he walked 37 batters. He moved around a lot in the Dodgers organization. Gleason joked that “they don’t even send me a contract anymore, they just mail me a new road map.” In 1966 he did manage to lead the Northwest League in homers, as well as in strikeouts. Roy got his draft notice in April 1967 and soon shipped out to Vietnam. In his eight months there he served with distinction, winning a Bronze Star for pulling three injured soldiers to safety. Promoted to the rank of sergeant, he led search-and-destroy missions. On one such assignment, an explosion sent shrapnel through his leg and left wrist. That was the end of his military service. Roy went back to baseball, although his grip was weak due to his wrist injury. After one more year in the Dodgers’ chain, he was drafted by the California Angels, who had him play in the Mexican League in 1970. Once again, he hit for power but struck out inordinately often. In January 1971 he was involved in a truck crash and suffered a broken collarbone. Trying to come back too soon, he reinjured it, bringing his playing career to an end.

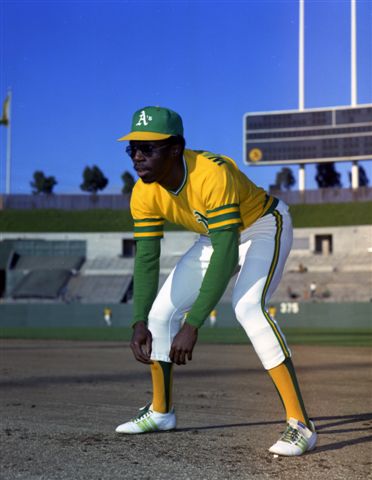

Charlie Finley had many innovative ideas as owner of the Athletics. One of these was to include on the roster a player just to pinch-run. While Herb Washington was the most notorious of these players, the first to embody Finley’s concept was Allan Lewis, the “Panamanian Express.” Born December 12, 1941, in Colon, Panama, Lewis attended Felix Olivares High School. Signing with the Kansas City Athletics in 1961, he spent his first season in Albuquerque in the Sophomore League. Lewis did well enough to earn a promotion to the Florida State League in 1962, which would be his home for most of the next five seasons. Although he maintained a good batting average there (.298), he rarely walked and hit for very little power. During the winters, he would return home to Panama and play in the winter league there. In 1965 he made the Florida State League all-star team, stealing 76 bases. That still wasn’t enough to earn him a further promotion, but he did finally grab Charlie Finley’s attention in 1966 by leading the league in runs and hits while stealing a league record 116 bases. The A’s purchased his contract and made him the subject of Finley’s great experiment. Earlier pinch-runners rarely stole bases but that was what Lewis was there for. In 28 pinch-running appearances in 1967, he stole 14 bases in 19 attempts. (In his minor-league career his success rate was greater than 80 percent.) Lewis spent part of the season with the Athletics’ Southern League team in Birmingham; he helped them to a pennant and hit .381 in the Dixie Series victory over Albuquerque of the Texas League. The A’s cut him from their roster after the season, but he wasn’t discouraged. In Panama that winter, he led the league with a .374 batting average as Balboa won the league championship. Lewis started the 1968 season in Birmingham and was promoted to the A’s, now in Oakland, in August. The next few years were more of the same; he split his time between playing full-time in the minors and pinch-running for the A’s. While Lewis could hit and field, he rarely got a chance to do so with the A’s; he had only 31 plate appearances in 156 games during his six seasons with them. Allan never really won the acceptance of his Oakland teammates; many thought his roster spot should have gone to a more complete player. Management didn’t always agree; when Reggie Jackson was hurt in the 1972 League Championship Series, they got permission to add Lewis to the World Series roster, and he pinch-ran in six of the seven games. Although he was caught stealing both times that he tried running on Johnny Bench, he did score the tying run in Game 4 and the final run in their 3-2 win in Game 7. Lewis’s last year in the major leagues was 1973; he suffered a dislocated shoulder just before spring training ended, and at 31 he seemed to have lost some speed; he stole only 7 bases in 11 attempts in 35 games, although he did score a career-high 16 runs. He also scored a big run in the League Championship Series. His teammates voted him only a one-tenth share of their World Series money; meanwhile, he was voted the most popular player on Birmingham by their fans. After his playing career, he worked as a coach in the Panama League and as a scout for the Cleveland Indians and the Phillies, becoming the Phillies’ Latin American scouting supervisor in 2003.

Charlie Finley had many innovative ideas as owner of the Athletics. One of these was to include on the roster a player just to pinch-run. While Herb Washington was the most notorious of these players, the first to embody Finley’s concept was Allan Lewis, the “Panamanian Express.” Born December 12, 1941, in Colon, Panama, Lewis attended Felix Olivares High School. Signing with the Kansas City Athletics in 1961, he spent his first season in Albuquerque in the Sophomore League. Lewis did well enough to earn a promotion to the Florida State League in 1962, which would be his home for most of the next five seasons. Although he maintained a good batting average there (.298), he rarely walked and hit for very little power. During the winters, he would return home to Panama and play in the winter league there. In 1965 he made the Florida State League all-star team, stealing 76 bases. That still wasn’t enough to earn him a further promotion, but he did finally grab Charlie Finley’s attention in 1966 by leading the league in runs and hits while stealing a league record 116 bases. The A’s purchased his contract and made him the subject of Finley’s great experiment. Earlier pinch-runners rarely stole bases but that was what Lewis was there for. In 28 pinch-running appearances in 1967, he stole 14 bases in 19 attempts. (In his minor-league career his success rate was greater than 80 percent.) Lewis spent part of the season with the Athletics’ Southern League team in Birmingham; he helped them to a pennant and hit .381 in the Dixie Series victory over Albuquerque of the Texas League. The A’s cut him from their roster after the season, but he wasn’t discouraged. In Panama that winter, he led the league with a .374 batting average as Balboa won the league championship. Lewis started the 1968 season in Birmingham and was promoted to the A’s, now in Oakland, in August. The next few years were more of the same; he split his time between playing full-time in the minors and pinch-running for the A’s. While Lewis could hit and field, he rarely got a chance to do so with the A’s; he had only 31 plate appearances in 156 games during his six seasons with them. Allan never really won the acceptance of his Oakland teammates; many thought his roster spot should have gone to a more complete player. Management didn’t always agree; when Reggie Jackson was hurt in the 1972 League Championship Series, they got permission to add Lewis to the World Series roster, and he pinch-ran in six of the seven games. Although he was caught stealing both times that he tried running on Johnny Bench, he did score the tying run in Game 4 and the final run in their 3-2 win in Game 7. Lewis’s last year in the major leagues was 1973; he suffered a dislocated shoulder just before spring training ended, and at 31 he seemed to have lost some speed; he stole only 7 bases in 11 attempts in 35 games, although he did score a career-high 16 runs. He also scored a big run in the League Championship Series. His teammates voted him only a one-tenth share of their World Series money; meanwhile, he was voted the most popular player on Birmingham by their fans. After his playing career, he worked as a coach in the Panama League and as a scout for the Cleveland Indians and the Phillies, becoming the Phillies’ Latin American scouting supervisor in 2003.

Donald Allen Wallace beat the odds to make the major leagues but couldn’t stick around for long. Born August 25, 1940, in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, where his father owned a service station. Don attended Oklahoma State University, where he played shortstop on the baseball team, which made it to the NCAA finals in 1961. As a junior and again as a senior, he was third-team All-American. Following his graduation in 1962, he signed a contract with the Baltimore Orioles organization and played for Aberdeen in the Northern League. Wallace led the league with a .325 batting average and drew 76 walks in 89 games. Following the season, he was claimed by the St. Louis Cardinals in the first-year player draft. Failing to make the Cardinals, he was sold back to the Orioles, who sent him to Elmira in the Eastern League. Playing mostly second base, he was named to the league all-star team and that fall was drafted again, this time by the New York Yankees. The Yankees played him in AAA for the next two years, the first in the International League, where he was voted Richmond’s most popular player and second fastest runner in the league. He also finished as runner-up for the Silver Glove award at shortstop for the second straight year. Then in 1966 he was optioned to Seattle, where as team MVP he helped the Angels to their first pennant in 11 years. That offseason saw him drafted for the third time, with Wallace becoming a member of the California Angels. Staying with the Angels for the first two months of the 1967 season, he saw action in 23 games, in 14 of them as a pinch-runner. He had some success in that role; in the April 21 game, he broke up a double play by avoiding the second baseman’s tag, and Jim Fregosi followed with a two-run game-winning home run. However, he failed a couple of times. The previous day he was caught stealing home for the last out of the game, and on May 30 he failed to tag up in time to score the tying run in the eighth inning. Wallace wasn’t a good enough hitter to win more playing time; his biggest weakness was an almost complete lack of power. On June 5, the Angels returned him to the minor leagues. Late that season, the Angels sent him to the Mets to complete an earlier deal for Hawk Taylor. Wallace had obtained a master’s degree in education and by 1965 had taken an offseason teaching job at a high school in Kansas City. Having advanced to the position of assistant principal by 1967, in 1968 he was unable to return to playing until June, after the school year ended. Barely a month later, he retired from baseball, turning full-time to his career in education.

Herman Hill spent parts of two seasons with the Minnesota Twins, mainly as a pinch-runner. Just as he seemed on the verge of breaking out of that role, tragedy struck. Born in Tuskegee, Alabama, on October 12, 1945, one of 13 children, Herman Alexander Hill signed with the Twins as an undrafted free agent in 1966. After struggling his first year in the Gulf Coast League, Hill made the necessary adjustments and in 1967 became a Florida State League all-star. Stealing 58 bases in 68 attempts, Herman led the league in on-base average. He started the next season in the Carolina League and quickly earned a promotion to the Southern League. A .300 batting average and 31 steals for Denver in 1969 (after stealing 36 bases for Charlotte the year before) encouraged the Twins to call Herman up in September. He got into 16 games for them, 13 as a pinch-runner, scoring four runs. Hill, a left-handed-hitting outfielder, was once timed at 9.5 seconds in the 100-yard dash and could get down to first base in 3.4 seconds. In the winter, he played for Caguas in Puerto Rico. He went back to AAA to start 1970 but was recalled by the Twins in June. He spent three weeks with Minnesota, getting into 14 games, playing center field and pinch-hitting as well as pinch-running, but a .105 on-base percentage sent him back to Evansville. In September he was back with the Twins and this time was used mainly as a pinch-runner. After the season, the Twins, looking to bolster their bullpen, traded Hill and a minor-leaguer to the st. Louis Cardinals in exchange for Sal Campisi and Jim Kennedy. Once again, Hill played winter ball, this time for Magallanes in Venezuela. On a day off there, Herman went swimming with his wife and some of his teammates. A powerful wave pulled him out to sea and, although the others tried to rescue him, one nearly dying in the attempt, Hill drowned. He was the third career pinch-runner to meet that fate.

John Robert Gamble Jr. was born February 10, 1948, in Reno, Nevada, to John Sr. and Muriel (Westergard) Gamble. A shortstop at Carson City High School, he was drafted in the second round of the June 1966 amateur draft by the Los Angeles Dodgers. Gamble played that summer and the next in the Pioneer League. He stole only 8 bases in those two seasons, but for Daytona Beach in the Florida State League in 1968 he swiped 38 in 46 tries. His hitting and fielding didn’t progress as quickly; he made 76 errors that year. After a brief stint in the California League in 1969, he spent the balance of that season and all of the next back with Daytona Beach, where he started playing third base. Although he had only a .298 slugging average in 1970, his 60 steals in 75 attempts were enough to get him drafted by the Detroit Tigers’ organization. With the Tigers, he advanced up to AA in 1971 and to AAA Toledo in 1972, splitting time between short and third. In September 1972 he was called up by the Tigers and got into six games with them, four as a pinch-runner. In 1973 he was back in Toledo but was recalled by the Tigers in mid-May. Gamble scored the winning run in his first game back as a pinch-runner with Detroit. The Tigers used him six more times, always as a pinch-runner, before returning him to the minor leagues. In 1974 the Tigers moved their AAA affiliation to Evansville in the American Association, and Gamble finished his career there in 1976.

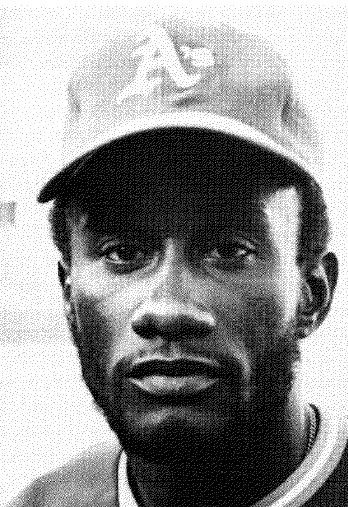

Perhaps the greatest pinch-runner in history, Matt Alexander pinch-ran 271 times, stealing 91 bases and scoring 89 runs, all records. He was born Matthew Alexander Jr. on January 30, 1947, in Shreveport, Louisiana. At Bethune High School, he was an all-city basketball player and also pitched on the baseball team. His senior year, 1965, he helped them to the Louisiana State AAA Championship, getting two pitching wins in the playoffs, including one against Vida Blue. Matt played baseball at Grambling State University, making the all-conference team twice, and was later named to the Southwest Athletic Conference Hall of Fame. Chosen by the Chicago Cubs in the second round of the June 1968 amateur draft after his junior year, Matt started his professional career in the Pioneer League. Alexander made the all-star team as a second baseman there, although he stole only two bases. An .825 OPS and 23 steals in 71 games in the Midwest League the next year earned him a midseason promotion to the Texas League. At this point, he served two years in the navy. On returning to civilian life, he went back to the Texas League, where he stole 38 bases in 41 attempts. Alexander was promoted to AAA in 1973 and got his first taste of the major leagues in August, seeing action in 12 games for the Cubs, mostly as a pinch-runner. The following season he was with the Cubs most of the year, getting a chance to play third base when Bill Madlock was hurt, but eventually a pulled leg muscle slowed him down. Since he was out of options, the Cubs sent him outright to Wichita after the season. And then, a week into the 1975 season, the Oakland A’s acquired him to be their newest “designated runner.” His new teammates, who were unhappy with the Herb Washington experiment and less than thrilled with having a second roster spot filled by runner Don Hopkins, soon took a liking to Alexander. Matt, who replaced Washington on the Oakland roster, was a switch-hitter who could play both infield and outfield and was a smart runner as well. Gene Tenace called him” 100 percent better than Hopkins or [Washington].” Alexander wasn’t used in any League Championship Series games that year, however. With the club weakened by free agency, the A’s gave up on Alexander after the 1977 season. Out of baseball, he started attending barber college back home in Shreveport. When rosters expanded in September 1978, though, the Pittsburgh Pirates signed him, and he would be with them on and off through the 1981 season. Although once again used mainly as a pinch-runner, Matt came through when asked to hit, going 12 for 27 with the Bucs. In 1979, when Pittsburgh won the NL East, Alexander finally got to participate in the postseason, scoring a run in his only LCS game and being caught stealing in Game 2 of the World Series. When the Pirates released him, he continued his playing career in the Mexican League. In 1983, at the age of 36, Matt proved he could still run, stealing a league-record 73 bases. He played a few more years in Mexico and then retired.

Perhaps the greatest pinch-runner in history, Matt Alexander pinch-ran 271 times, stealing 91 bases and scoring 89 runs, all records. He was born Matthew Alexander Jr. on January 30, 1947, in Shreveport, Louisiana. At Bethune High School, he was an all-city basketball player and also pitched on the baseball team. His senior year, 1965, he helped them to the Louisiana State AAA Championship, getting two pitching wins in the playoffs, including one against Vida Blue. Matt played baseball at Grambling State University, making the all-conference team twice, and was later named to the Southwest Athletic Conference Hall of Fame. Chosen by the Chicago Cubs in the second round of the June 1968 amateur draft after his junior year, Matt started his professional career in the Pioneer League. Alexander made the all-star team as a second baseman there, although he stole only two bases. An .825 OPS and 23 steals in 71 games in the Midwest League the next year earned him a midseason promotion to the Texas League. At this point, he served two years in the navy. On returning to civilian life, he went back to the Texas League, where he stole 38 bases in 41 attempts. Alexander was promoted to AAA in 1973 and got his first taste of the major leagues in August, seeing action in 12 games for the Cubs, mostly as a pinch-runner. The following season he was with the Cubs most of the year, getting a chance to play third base when Bill Madlock was hurt, but eventually a pulled leg muscle slowed him down. Since he was out of options, the Cubs sent him outright to Wichita after the season. And then, a week into the 1975 season, the Oakland A’s acquired him to be their newest “designated runner.” His new teammates, who were unhappy with the Herb Washington experiment and less than thrilled with having a second roster spot filled by runner Don Hopkins, soon took a liking to Alexander. Matt, who replaced Washington on the Oakland roster, was a switch-hitter who could play both infield and outfield and was a smart runner as well. Gene Tenace called him” 100 percent better than Hopkins or [Washington].” Alexander wasn’t used in any League Championship Series games that year, however. With the club weakened by free agency, the A’s gave up on Alexander after the 1977 season. Out of baseball, he started attending barber college back home in Shreveport. When rosters expanded in September 1978, though, the Pittsburgh Pirates signed him, and he would be with them on and off through the 1981 season. Although once again used mainly as a pinch-runner, Matt came through when asked to hit, going 12 for 27 with the Bucs. In 1979, when Pittsburgh won the NL East, Alexander finally got to participate in the postseason, scoring a run in his only LCS game and being caught stealing in Game 2 of the World Series. When the Pirates released him, he continued his playing career in the Mexican League. In 1983, at the age of 36, Matt proved he could still run, stealing a league-record 73 bases. He played a few more years in Mexico and then retired.

The Oakland A’s, happy enough with their “designated runner” experiment in 1974, decided to add a second such speedster in 1975, although this one would be a real baseball player, Don Hopkins. Hopkins was born January 9, 1952, in West Point, Mississippi. He starred in four sports at Benton Harbor High School. Hopkins helped the baseball team to the Michigan state championship; he also ran a 9.5 second 100-yard dash for the track team. After high school, he signed as an undrafted free agent with the Montreal Expos. After a brief stint in the Gulf Coast League in 1970, he advanced to the Class A Northern League in 1971. Here he first showed his ability as a base stealer. Despite garnering only 39 hits in 191 at-bats, he stole a league-leading 39 bases. An .843 fielding average as an outfielder showed his weakness with the bat was matched by his glove. The following year, he set a New York-Pennsylvania League record with 63 stolen bases. Hopkins was thrown out only 9 times in 70 games. He split 1973 between the Florida State and Eastern Leagues, stealing an additional 58 bases, including 5 in one game for Quebec City. A .232 slugging average in the Eastern League, though, overshadowed his running. In 1974 he finally showed some promise with the bat, managing a .366 on-base average in the Carolina League. He also saw time in AA and AAA that year. Near the end of spring training in 1975, his contract was purchased by the Oakland A’s. The idea was to have another runner who, like Allan Lewis, could be used in the field and could hit when needed. However, the reality was that Hopkins rarely did either, playing only 10 innings in the outfield and getting only 8 plate appearances in his 82 games in 1975. His 74 games as a pinch-runner is second only to Herb Washington’s 92 in 1974. In addition, Hopkins in the major leagues wasn’t as successful on the bases as he had been in the minors. He carried a career 84 percent success rate in the minors but had stolen only 15 bases in 24 attempts when the A’s sent him back to AAA in early August. He did better when recalled in September, stealing 6 bases in as many tries, but in 1976 the A’s decided they could get along without his services, bringing him back in September for just three more pinch-running appearances. After one more year in AAA, his playing career came to an end.

After Matt Alexander’s release in 1977, the Oakland A’s waited less than a year to add another pinch-runner to their roster. Darrell Lee Woodard was born December 10, 1956, in Wilmar, Arkansas, to Eardee and Arthalene (Sanders) Woodard. At Bell High School in Los Angeles, California, he earned letters in four sports. After high school he signed with the A’s as an undrafted free agent. A shortstop, he spent his first two years in professional ball in the short-season Northwest League. In 1975, he led the league in fielding average as the league’s all-star shortstop and had a fine .408 on-base average. However, he had only seven extra base hits in 246 at-bats. He spent the next two seasons in the California League, reaching base at a good rate but showing almost no power. Woodard shifted to second base during the 1976 season. In 1977, teamed with Rickey Henderson on Modesto, Woodard stole a remarkable 90 bases in 97 attempts, while Henderson added a league-leading 95 steals. The following year saw him playing in the AA Eastern League; in August he was brought up to the A’s. In his first game, on August 6, he scored the winning run as a pinch-runner. Darrell got into 33 games with Oakland, 22 as a pinch-runner. He also saw action at second base and even once at third but failed to get a hit in nine at-bats. As a pinch-runner, his success was mixed, being thrown out stealing four times in seven attempts but also scoring nine times. The following year he was involved in an unusual transaction as the A’s sent him and another player to the Miami team in the new Inter-American League in exchange for George Mitterwald, who was to serve as Oakland’s bullpen coach. Miami won both halves of the abbreviated season; when the league ceased play on June 30, Woodard joined Midland in the Texas League before finishing the year with Wichita in the American Association. Darrell started in the South Atlantic League in 1980 and worked his way back to AA, playing for Birmingham in the Southern League in 1981 and 1982, but Woodard’s playing career ended there.

Alberto Lois was once called “a young Roberto Clemente.” Like Clemente, he was sometimes accused of malingering, and his career ended prematurely. Unlike Clemente, however, he never became a star. Alberto Lois was born May 6, 1956, in Hato Mayor, Dominican Republic, to Eligio and Lucio (Feliciano) Lois. He was signed for the Pittsburgh Pirates by legendary scout Howie Haak in 1974. That year he played 119 games in the Western Carolinas League, stealing 37 bases in 49 attempts. However, he would never playas many as 100 games in any subsequent season. Repeated injuries, some of which the Pirates suspected were not serious enough to keep him out of the lineup, limited his playing time. Lois also reported late to spring training each year, causing the Pirates to question his desire. Nelson Norman, former Pirates shortstop, who played ball with Lois when they were youngsters, said Lois was undisciplined and yet so talented that he would come to a game drunk and still get two or three hits. Still, he advanced rapidly through their farm system. In 1976, 12 triples and 24 stolen bases in 65 games in the Texas League led to his promotion to AAA. He closed the season in Charleston of the International League with a .300 batting average. In 1977, he got off to a fast start at Columbus but the injury bug struck again, and Lois played only 42 games that year. He was hurt again in 1978, and he spent time down in the Carolina League getting some playing time. Come September, though, the Pirates called him up, although he would see limited action. It was pretty much the same story in 1979. This time, however, he was recalled in mid-August for a week and then again in September, doing nothing but pinch-running in 11 games, scoring six times. During the winter, Alberto returned home and played in the Dominican Winter League. Then a tragedy brought his playing career to a screeching halt. On his way home from a game, driving a truckload of friends, he tried to beat a train to a crossing and failed. The resulting collision cost the lives of six of his passengers. Lois’s right eye was injured in the wreck, and his impaired vision left him unable to play again.

Thaddeaus Inglehart (Ted) Wilborn was born December 16, 1958, in Waco, Texas, to Charles and Yvonne (Inglehart) Wilborn. His brother Chuck played several years in the San Diego Padres’ organization. Ted was drafted in the fourth round of the June 1976 amateur draft by the Yankees and was assigned to Oneonta of the New York-Pennsylvania League, where he struggled. His second season in pro ball was spent in the Florida State League, where he also had trouble hitting, although he did draw 45 walks in 262 plate appearances. It was his third season that was his breakthrough year, 1978. Formerly a left-handed hitter, he starting switch-hitting. Sent back to the NYP, Wilborn stole 57 bases in just 65 games for Oneonta. Combined with a .428 on-base percentage, that was enough to induce the Toronto Blue Jays to make him a Rule 5 draftee. Required by the rules to keep him on their active roster for three months or risk losing him, the Blue Jays used Wilborn in 22 games, 15 as a pinch-runner, before optioning him to the International League. Following the season, the Yankees reobtained Wilborn in a multiplayer trade. They sent the switch-hitting outfielder to their Nashville farm team, recalling him in September. Ted got into eight games with New York, pinch-running in four of them. That was the end of his major-league career. He spent 1981 back in Nashville, leading the Southern League in runs scored and for the first time playing some at second base. After the season, Wilborn was traded to the San Francisco Giants along with Andy McGaffigan for Doyle Alexander. Ted spent several more years playing minor-league ball. His playing career came to an end after just one game in the International League in 1987.

CLIFFORD BLAU is a retired CPA whose articles have appeared in the “Baseball Research Journal” and “The Best of By The Numbers.” A member of SABR since 1983, he enjoys combining his loves of baseball and music. Cliff operates a website on baseball research, which includes a history of league operating rules and other issues, at cliffblau.com.

Sources

Baseball Magazine, Binghamton Press, Boston Herald, Chicago Tribune, Hartford Courant, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Portsmouth Times, Scioto Voice, Tacoma News Tribune, Tennessean, The Sporting News, Washington Post

Ancestry.com. http://www.ancestry.com.

Arkush, Michael. “Five-Star Ball Player: Roy Gleason.” The VVA Veteran, May/June 2004.

Baseball Almanac. “Grambling State University Baseball Players Who Made It to the Major Leagues.” http://www.baseball-almanac.com/college/grambling_state_university_baseball_players.shtml.

Baseball Reference. www.baseball-reference.com/.

Tony Grullon. “Beisbol y Salud.”

Biographical Register of the Department of State, 1974.

College Football Data Warehouse. “John R. ‘Dinny’ McNamara Records by Year.” http://cfbdatawarehouse.com.

Figuerdo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball; A Statistical History, 1878-1961. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003.

Heritage Quest. www.heritagequestonline.com/hqoweb/library/do/index.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. Durham, N.C.: Baseball America, 1997.

Lee, Bill. The Baseball Necrology. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003.

Marazzi, Richard. Aaron to Zipfel. New York: Avon Books, 1985.

Marazzi, Richard, and Len Fiorito. Baseball Players of the 1950s; A Biographical Dictionary of All 1,560 Major Leaguers. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004.

Moffi, Larry, and Jonathan Kronstadt. Crossing the Line; Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1994.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

New York Public Library.

Pioneer League.

Ruck, Robert. The Tropic of Baseball; Baseball in the Dominican Republic. Westport, Conn.: Meckler Publishing, 1990.

Rutgers University Athletics.

Society for American Baseball Research Collegiate Committee database.

Society for American Baseball Encyclopedia.

Society for American Baseball Research Scouts Committee.

Society for American Baseball Research. Minor League Baseball Stars, revised edition. Cleveland: SABR, 1984.

The Sporting News. Official Baseball Register. Charlotte, N.C.: The Sporting News.

The VVA Veteran.

Wright, Marshall. The International League Year-by-Year Statistics, 1884-1953. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1998.