Soderholm-Difatte: The 1914 Stallings Platoon: Assessing Execution, Impact, and Strategic Philosophy

Editor’s note: This article by Bryan Soderholm-Difatte from the Fall 2014 “Baseball Research Journal” is a finalist in the Historical Analysis/Commentary category for the 2015 SABR Analytics Conference Research Awards. Voting for the winners will be conducted online from Friday, January 30 to Monday, February 16, 2015. The winners will be announced at the fourth annual SABR Analytics Conference, March 12-14, 2015, in Phoenix, Arizona. Learn more at SABR.org/analytics.

By Bryan Soderholm-Difatte

This year marks a century since the historic run of the 1914 Boston “Miracle” Braves. They were dead last in the National League on July 4, 15 games behind John McGraw’s pace-setting New York Giants, who seemed well on their way to a fourth straight pennant. They famously overtook the Giants in early September, ultimately claiming the National League pennant by a margin of 10 1?2 games. They capped the year with a World Series sweep of Connie Mack’s imposing Philadelphia Athletics—the very same A’s who had won four pennants in five years and three of the four previous Fall Classics.

This team of destiny was managed by George Stallings who, like Mr. Mack, gave directions from the dugout dressed in civilian business attire. Stallings reportedly said, “Give me a ball club of only mediocre ability, and if I can get the players in the right frame of mind, they’ll beat the World Champions.”[fn]Stallings as quoted by Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves: 1871–1953 (Northeastern University Press, 2004), 138. [/fn] Historical retrospection has attributed the Braves’ 1914 “miracle” to more than just team motivation, however. The accepted wisdom is that Stallings had an epiphany about platooning and that his use of platoons to wring the maximum production from his roster was, in the words of Bill James, nothing short of “revolutionary.”[fn]Bill James, for example, writes in his book on baseball managers, “In 1914 Stallings platooned at all three outfield positions. [His team] stunned the baseball world by surging to the 1914 pennant, then defeating the mighty A’s in four straight. This event had tremendous impact on other managers, almost revolutionary impact, as opposed to evolutionary. Managers had platooned a little bit here and there since the 1880s, but it was very rare…” Bill James, The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers From 1870 to Today (New York: Scribner, 1997).[/fn]

This team of destiny was managed by George Stallings who, like Mr. Mack, gave directions from the dugout dressed in civilian business attire. Stallings reportedly said, “Give me a ball club of only mediocre ability, and if I can get the players in the right frame of mind, they’ll beat the World Champions.”[fn]Stallings as quoted by Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves: 1871–1953 (Northeastern University Press, 2004), 138. [/fn] Historical retrospection has attributed the Braves’ 1914 “miracle” to more than just team motivation, however. The accepted wisdom is that Stallings had an epiphany about platooning and that his use of platoons to wring the maximum production from his roster was, in the words of Bill James, nothing short of “revolutionary.”[fn]Bill James, for example, writes in his book on baseball managers, “In 1914 Stallings platooned at all three outfield positions. [His team] stunned the baseball world by surging to the 1914 pennant, then defeating the mighty A’s in four straight. This event had tremendous impact on other managers, almost revolutionary impact, as opposed to evolutionary. Managers had platooned a little bit here and there since the 1880s, but it was very rare…” Bill James, The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers From 1870 to Today (New York: Scribner, 1997).[/fn]

Until now, however, we did not have the means to prove that platooning made the difference. Thanks to the painstaking work of researchers for Retrosheet, comprehensive data on starting line-ups are now available for 1914 and reproduced at Baseball-Reference.com. For the first time it is possible to dissect with precision Stallings’s master manipulation of his outfielders. Stallings employed a three-position rotation to cover weaknesses and keyed the surge to overtake McGraw’s Giants.

PLATOONING TO MASK WEAKNESSES

When Stallings assumed command in 1913, the once-dominant (in the 1890s) National League franchise in Boston had not lost fewer than 90 games since 1903, when they lost 80 in a 140-game schedule. Recasting the roster and proving a tough taskmaster, Stallings immediately turned the team around, guiding the Braves into fifth place with a 69–82 record. However, even though a writer for Baseball Magazine, the preeminent publication on the sport at the time, claimed the Braves had a sufficiently “formidable ball club” to finish second or third in 1914, nobody expected them to beat the Giants.[fn]William A. Phelon, “The Big League Pennant Winners,” Baseball Magazine (May 1914): 17–18.[/fn] Pitching was a particular strength, headlined by right-handers Dick Rudolph and Bill James, who won 26 games apiece, and Lefty Tyler, who had 16 wins. Rudolph went 20–2 and James 19–1 after July 4, while Tyler was 10–5.

Boston’s only position players of note were second baseman Johnny Evers and shortstop Rabbit Maranville, whose excellence on the field of play earned them first and second in the Chalmers Award (most valuable player) voting in 1914. Both players are in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown but neither is widely considered to have been one of the all-time greats at his position. Maranville, in his second year as the Braves’ shortstop, was young, energetic, and feisty, while Evers was a 13-year veteran acquired from the Cubs for being sage, savvy, and ultra-competitive. It was his arrival that spurred some writers to preseason optimism about the Braves. With Maranville and Evers anchoring the middle, Stallings’s infield was set for the season. Butch Schmidt, in his first full major league season, started all but 11 games at first base. Third base was covered by Charlie Deal until the arrival of Red Smith, acquired from Brooklyn in a midseason trade because he was a much better hitter than Deal. Hank Gowdy caught 115 games, second in the league only to the Giants’ Chief Meyers.

Stallings’s outfield, however, was a mess. Previewing the season for Baseball Magazine, writer Fred Lieb projected that fourth place was the best that could be expected of the Braves because “you can’t do much with an outfield composed of Connolly, Mann and Griffith.”[fn]Frederick G. Lieb, “How Will They Finish Next October?” Baseball Magazine (March 1914): 45.[/fn] Joe Connolly, Les Mann, and Tommy Griffith had been rookies in 1913. Connolly played in 126 games, Mann in 120, and Griffith in only 37, having not joined the big club until August. The left-handed-hitting Connolly showed the most promise in the batter’s box that season. He tied for the team lead in home runs with five, led the Braves in RBIs with 57, and his .281 batting average was the highest among Stallings’s regulars.

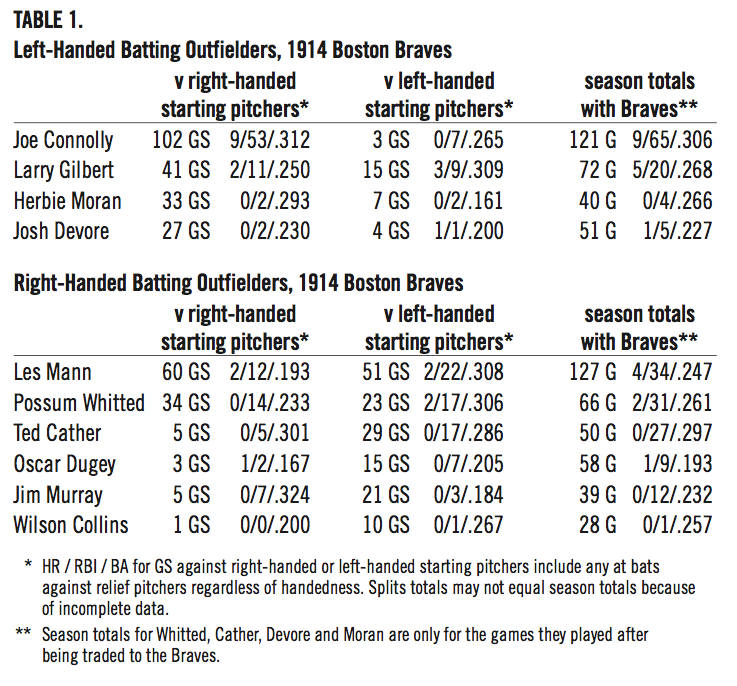

With limited major-league experience among those three, and poor talent to be found among their peers, Stallings rotated the seven to eight outfielders he had on his roster at any one time through the three positions. Stallings used a total of eleven different players in the outfield that year. Stallings began the season with three left-handed and three right-handed outfielders, one of whom—Oscar Dugey—could also substitute at any infield position. He ended the season with four left-handed and four right-handed outfielders, two of whom—Dugey and Possum Whitted— could also play in the infield. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

(click image to enlarge)

Connolly continued to be the only truly productive outfielder, at least as measured by wins above replacement (WAR) at Baseball-Reference.com with 3.8. Though he appeared in only 121 games in 1914, he led the team in home runs with nine and had the highest on-base and slugging percentages on the Braves. His 65 RBIs were third on the team to Maranville and Schmidt, but the shortstop, playing in all but two of Boston’s games, had nearly 200 more plate appearances and the first baseman, playing in 147 games, had 145 more plate appearances to knock in six more runs than Connolly. Smith was the only batter in the lineup to hit for an average higher than Connolly’s .306, but Smith had nearly 200 fewer at bats with the Braves. Even though Connolly played in only 121 games, and almost never against left-handed pitching, he was still the team’s best and most dangerous hitter, according to the offense component of WAR.[fn]Rabbit Maranville, with 5 wins above replacement (WAR), and Johnny Evers, with a 4.9 WAR, both had a higher overall player value than Connolly’s 3.8 WAR, but a significant portion of their value was their fielding. Connolly’s 3.9 offensive WAR was the highest on the team, with Evers second at 3.2.[/fn]

The ten other players used in the outfield by Stallings in 1914 had a collective player value 0.2 wins less than a replacement-level player; only left-handed Les Mann (1.5 WAR) and left-handed Larry Gilbert (0.6 WAR) and the right-handed Whitted (whose 0.9 WAR with Boston—he began the year in St. Louis—included 26 games in the infield) had even marginal value for a major league player by the WAR metric. Stallings’s brilliance was to have the insight to play them all in a way to give his team comparative batter-pitcher advantages from game-to-game, and even take account of pitching changes within games.

The Braves played 158 games on their way to a 94–59 record, including five that were tied when called because of darkness or weather. Platooning at all three outfield positions, Stallings’s starting lineups had at least two of his three outfielders batting from the opposite side of the starting pitcher’s throwing arm in all but 11 of the Braves’ games, and 44 times during the season—28 percent of their total games—all three starting outfielders had the platoon advantage against the opposing pitcher. Les Mann started 111 games in the outfield, the most of any Braves outfielder, 94 of them in center, followed by Connolly with 105 starts, all but two in left field. Larry Gilbert was third with 56 outfield starts, 48 in right field. All three played for Boston the entire season.

The Braves played 158 games on their way to a 94–59 record, including five that were tied when called because of darkness or weather. Platooning at all three outfield positions, Stallings’s starting lineups had at least two of his three outfielders batting from the opposite side of the starting pitcher’s throwing arm in all but 11 of the Braves’ games, and 44 times during the season—28 percent of their total games—all three starting outfielders had the platoon advantage against the opposing pitcher. Les Mann started 111 games in the outfield, the most of any Braves outfielder, 94 of them in center, followed by Connolly with 105 starts, all but two in left field. Larry Gilbert was third with 56 outfield starts, 48 in right field. All three played for Boston the entire season.

The turning point for the Braves that made their 1914 miracle possible was June 28, with the team mired in last place and the season already a major disappointment based on preseason expectations. June 28 was an off-day because Boston city ordinances prohibited playing baseball on Sundays, but they apparently did not prohibit baseball transactions. On that day the Braves traded right-hander Hub Perdue, who had tied Lefty Tyler’s 16 wins for most on the team in 1913 but was struggling badly this season, to the St. Louis Cardinals for outfielder Ted Cather and utility player Possum Whitted, both right-handed batters. Five days later, the Braves traded with the Phillies for the left-handed batting Josh Devore, who had once been a regular for John McGraw in the Giants’ outfield. And on August 23, the Braves acquired another left-handed batting outfielder, Herbie Moran, in a cash transaction with the Cincinnati Reds. Boston was a half-game out of first place on the day they acquired Moran.

Although none of the four was better than a marginal big league player that year according to WAR, each of those transactions proved instrumental in shoring up the Braves’ outfield. Cather and Whitted essentially replaced right-handed outfielders Jim Murray and Wilson Collins in Stallings’s outfield rotation. Murray was picked up from the minor leagues about a week into the season and moved into the right-handed half of the right field platoon, starting 21 games against southpaws and five against right-handers. Murray had had a long, distinguished career in the minors, but this was only his third time in the big leagues, having also played briefly for the 1902 Cubs and the 1911 Browns. He was no more successful this time, hitting only .232 in 39 games for the 1914 Braves and a mere .184 in his starts against southpaws, where his platoon advantage proved to be anything but.

Collins, whose only prior big league experience was 16 games with the Braves the previous year in which he got only three at bats, started 10 games against southpaws in 1914, also mostly in right field, without making much of an impact. Once Stallings had Cather and Whitted in hand, Murray and Collins were expendable. Neither played in another major league game after July 10. Used by his manager almost exclusively against lefties, Cather hit .297 in 50 games for the Braves, making 34 starts.

Whitted started 37 games in the outfield and another 20 in the infield (mostly second base), batting .261. On the strength of 11 extra-base hits, a .293 batting average and 26 RBIs in September and October, Whitted ended the season as a daily regular in Stallings’s lineup, playing most often in center field, starting in the team’s final 34 games—21 against right-handed starting pitchers—batting mostly clean-up against lefties and righties alike.

The acquisitions of Devore and Moran were just as consequential. Tommy Griffith had started the season as the left-handed bat in Stallings’s right field platoon, but after 16 games in which he hit an abysmal .104, Griffith was sold to Indianapolis in mid-May. This left Stallings with Connolly and Gilbert as his only two left-handed hitting outfielders for nearly seven weeks until he picked up Devore on July 3. Playing both center and right fields, Devore started 31 games for the Braves in the summer and fall of 1914, almost exclusively against right-handed starting pitchers, although his batting average of .227 was not much to brag about. Since right-handed pitchers in baseball outnumbered southpaws by nearly three-to-one, trading for Devore gave Stallings more flexibility to both platoon his starting lineup and make in-game substitutions. It surely did not hurt, therefore, to add Moran as a fourth left-handed outfielder as the Braves began their stretch run. Moran was a constant in Stallings’s lineup from then till the end of the season, starting in 40 of the Braves’ remaining 49 games; lefties took the mound against the Braves in all nine of the games he did not start.

MIXING ‘EM UP

Stallings was superb in how and when he rotated his outfielders into the lineup and into the games they did not start. Of the players that he platooned in 1914, only the right-handed Mann and Whitted started a significant number of games against pitchers throwing from the same side they hit. Although each started more games against righties, Stallings’s inclination to platoon both players was spot on. Mann hit .247 for the season, but only .193 in 76 games against righties, while in the 51 games he started against lefties he hit .308. Including 31 at bats for the Cardinals before being traded, Whitted batted .215 against righties in 1914 compared to .286 against lefties, against whom he hit both his home runs.[fn]Player splits for 1914 at Baseball-Reference.com include how the batter did in games started by a right-hander or a left-hander, including any pitcher in relief regardless of which side he threw from.[/fn]

Unlike with Mann and Whitted, Stallings rarely saw fit to start one of his left-handed outfielders when a southpaw started against Boston. It was conventional wisdom even a century ago, as it is today, that left-handed batters have more difficulty hitting southpaws than right-handed batters do against northsiders.[fn]See James Click in Baseball Between the Numbers: Why Everything You Know About the Game is Wrong, ed. by Jonah Keri (Basic Books, 2006), 347.[/fn] In the first half of the season, when neither Murray nor Collins was making much of a contribution, Stallings started Larry Gilbert in 15 games against lefties. After Whitted and Cather joined the club, Stallings rarely started a left-hander in his outfield when a southpaw took the mound until he did so with Moran in seven games in the September-October stretch. Gilbert, with a .268 average on the season, batted .309 in games started by lefties, including four he did not start. Moran batted .293 in games started by right-handed opponents, but only managed .161 versus lefties.

Stallings’s unwillingness to use the left-handed Joe Connolly against lefties, meanwhile, mystified at least one baseball writer at the time because Connolly was the Braves’ most dangerous and potent hitter, certainly against right-handers.[fn]“For some reason [Stallings] withdraws Joe from the line-up when a southpaw is opposing the Braves,” wrote Samuel M. Johnston in, “Good Natured Joe Connolly: The Man Who Always Smiles,” Baseball Magazine (February 1915): 27.[/fn] While that writer made sure to say the left-handed Connolly “never had any trouble in hitting the southpaws in the minors,” Stallings begged to differ. Connolly started only three games against lefties, but Stallings inserted him into 16 games after the opponent’s left-handed starter had been replaced by a right-hander reliever, usually as a pinch hitter who then stayed in the game to play left field. In three of those games, he was later removed when another southpaw came in to pitch. Connolly batted .304 coming off the bench when a right-hander came into the game; his average in the games he started against right-handers was .312, and all nine of his team-leading home runs were against righties. It is also worth noting that Stallings removed Connolly from 16 games, most often due to the insertion of a left-handed reliever.

Connolly’s entire major-league career was as a platoon player for Stallings, who never gave him the opportunity to play regularly against southpaws. From 1914 until he left baseball in 1916, Connolly started in 207 games for Boston, but only five when a left-hander took the mound. Appearing in a total of 42 games started by a lefty those three years, Connolly hit only .258 in 62 at bats, compared to a robust (for the era) .296 with nine home runs against righties. Lefty-righty splits are not available for Connolly’s rookie season of 1913, but the fact he appeared in only 126 games and that otherwise it was almost all right-handed batters who played in left field suggests Stallings decided in his very first year as Braves manager that Connolly (however successful he may have been hitting southpaws in the minor leagues) was so fundamentally flawed a hitter against left-handers that he was unlikely to improve.

Besides platooning his outfielders in the starting lineup from the very first day of the season, Stallings also often replaced his outfielders during the game depending on circumstances, particularly when the opposing team brought in a reliever who threw from the opposite side of the day’s starting pitcher. In all, Stallings made in-game outfield substitutions 87 times during the regular season. Many of these substitutions occurred as soon as a pitching change was made, with the replacement player taking his position in the field rather than waiting to pinch hit for the starting outfielder when his turn came to bat against the new pitcher. The Braves faced a left-handed reliever in 23 of the 102 games started against them by a right-hander, and a right-handed pitcher came in to relieve in 24 of the 56 games started by a lefty. Not including pinch hitters for the pitcher who did not stay in the game in a double switch, Stallings substituted for a position player at least once in 84 of the Braves’ 158 games—58 times in games started by a right-hander against them, and 26 times in games started by a lefty. However, not all of Stallings’s in-game position player substitutions were necessarily to counter a pitching change.

THE BRAVES’ COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE

By platooning his outfield, Stallings was able to maximize the offensive possibilities of his starting lineup regardless of whether the opposing starting pitcher was righty or lefty. This was particularly important because the 1914 Boston Braves had the third-lowest offensive WAR (16.1) as a team in the National League; the five teams with more potent offensives averaged 20.5 offensive wins above replacement. What made his outfield platoon rotation so effective, however, was quite likely Stallings’s ability to take advantage of the fact that two of his infield regulars—first baseman Butch Schmidt and second baseman Johnny Evers—were both left-handed batters. No other National League team had more than one infield regular who batted from the left side.[fn]Giants’ second baseman Larry Doyle and Cardinals’ second baseman Miller Huggins—a switch hitter—were the only starting infielders in the National League besides Evers to bat left-handed and play at a position other than first base. Brooklyn, Chicago, Cincinnati (until Dick Hoblitzel was waived in mid-season) and Philadelphia had left-handed first basemen starting regularly for them.[/fn] This meant that Stallings usually had four or five left-handed bats in his lineup against right-handed starting pitchers. Most other managers, with only one left-handed batting infielder at most, and generally wedded to the same starting outfielders game in and game out, could count on no more than three left-handed batters against right-handed starting pitchers. When 71 percent of National League games were started by right-handers, Stallings’s outfield platoon plus Schmidt and Evers batting from the left side gave Boston an advantage of no small import.

By platooning his outfield, Stallings was able to maximize the offensive possibilities of his starting lineup regardless of whether the opposing starting pitcher was righty or lefty. This was particularly important because the 1914 Boston Braves had the third-lowest offensive WAR (16.1) as a team in the National League; the five teams with more potent offensives averaged 20.5 offensive wins above replacement. What made his outfield platoon rotation so effective, however, was quite likely Stallings’s ability to take advantage of the fact that two of his infield regulars—first baseman Butch Schmidt and second baseman Johnny Evers—were both left-handed batters. No other National League team had more than one infield regular who batted from the left side.[fn]Giants’ second baseman Larry Doyle and Cardinals’ second baseman Miller Huggins—a switch hitter—were the only starting infielders in the National League besides Evers to bat left-handed and play at a position other than first base. Brooklyn, Chicago, Cincinnati (until Dick Hoblitzel was waived in mid-season) and Philadelphia had left-handed first basemen starting regularly for them.[/fn] This meant that Stallings usually had four or five left-handed bats in his lineup against right-handed starting pitchers. Most other managers, with only one left-handed batting infielder at most, and generally wedded to the same starting outfielders game in and game out, could count on no more than three left-handed batters against right-handed starting pitchers. When 71 percent of National League games were started by right-handers, Stallings’s outfield platoon plus Schmidt and Evers batting from the left side gave Boston an advantage of no small import.

It is therefore not surprising that with Evers and Schmidt in the lineup every day that they were healthy and Connolly the Braves’ most dangerous hitter, Boston faced as many left-handed starters—56—as any other National League team.[fn]Also facing 56 left-handed starting pitchers during the 1914 season were the St. Louis Cardinals, three of whose regulars were either switch hitters or a left-handed batter; the Chicago Cubs, whose left-handed batting first baseman, Vic Saier, was one of baseball’s premier sluggers, knocking out 18 home runs (one short of the major-league lead); and the Brooklyn Dodgers, whose right fielder, Zach Wheat, was one of the league’s premier left-handed batters.[/fn] In 80 of the 102 games where the Braves faced a right-handed starting pitcher, Stallings had at least four left-handed batters in his lineup, and in 14 of those games Stallings started five left-handed position players: three outfielders, Evers, and Schmidt.

In eight other games against right-handed starters, all three outfielders in Stallings’s starting lineup batted from the left side, but either Schmidt or Evers was sidelined because of an injury or being rested. In four straight games at the end of August and four straight games at the beginning of September, opposing right-handed starting pitchers were faced with a batting order whose first five hitters were all left-handed: Moran leading off, Evers, Connolly, Gilbert batting clean-up, and Schmidt. By the same token, in 39 of the 56 games the Braves faced southpaw starters, Stallings overloaded his line-up with at least six right-handed batters—usually with three right-handed outfielders—leaving daily regulars Evers and Schmidt as the only lefties in the batting order.

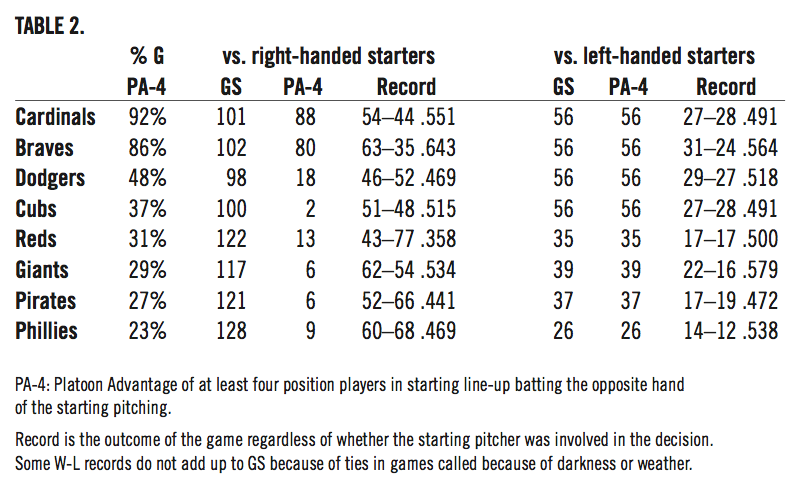

Stallings’s outfield mixing and matching gave the Braves a platoon advantage in his batting order of at least four of eight position players in 86 percent of their games, and a platoon advantage of at least five in 44 percent of their games. The only National League team to exceed the Braves in proportion of games in which the opposing starting pitcher had to face at least four batters with a platoon advantage was the St. Louis Cardinals, who benefited from having two regulars who were switch hitters (second baseman Miller Huggins and outfielder Lee Magee), their everyday right fielder (Owen Wilson) being a left-handed hitter, and player-manager Huggins using a lefty-righty platoon at one outfield position most of the entire season.

While every team was able to bat at least four right-handers in every game they faced a southpaw starting pitcher, it was rare for teams other than Boston and St. Louis to start four left-handers in a game against right-handed pitchers. Consequently, no other team came close to the Cardinals and Braves in having a platoon advantage of four batters or more in the overwhelming majority of their games. (See Table 2.)

Table 2

(click image to enlarge)

As Table 2 also shows, the payoff for the Boston Braves was that their 31 victories in games started against them by lefties was the best in the league, and even more significantly, in games started against them by right-handers, the Braves’ 63–35 record was by far the best winning average (.643) of any National League team.[fn]The Cardinals, with a lineup of at least four left-handed batters in 88 of the 101 games they faced a right-handed starting pitcher, had the second-best record after the Braves against righties.[/fn] Those won-lost records take into account all pinch hitting and position player substitutions Stallings made when a relief pitcher of either handedness was brought into the game against his team. Only the American League champion Philadelphia Athletics had a better record against right-handed starters. Why? Because Connie Mack had the advantage of five left-handed batters among his core regulars—infielders Eddie Collins and Home Run Baker, outfielders Amos Strunk and Eddie Murphy, and switch-hitting catcher Wally Schang—none of whom he made part of any platoon when writing out his starting lineups.

In the crucible of a World Series against the heavily favored Philadelphia Athletics powerhouse, Stallings stayed with what worked during the season. Connolly and Moran, both left-handed, started only three games in the Braves’ World Series sweep. As he had in all but three games all season, Stallings benched Connolly in Game Two when southpaw Eddie Plank took the mound for Philadelphia, starting the right-handed Ted Cather in left field instead. Stallings also benched Moran in that game in favor of the right-handed hitting Les Mann in right field. And in the fourth and final game of the Series, Connolly was pinch hit for, and then replaced in left field, by Mann as soon as Athletics’ right-handed starter Bob Shawkey was relieved by lefty Herb Pennock in the sixth inning. With the Braves in front when it came Moran’s turn to bat for the first time against Pennock, Stallings elected to keep him in the game.[fn]Moran had only one hit in 13 at-bats in the Series and Connolly only one hit in nine at bats. That Connolly had only one RBI in the Series was surely a disappointment, but that came on his sacrifice fly off right-hander Bullet Joe Bush to drive home the tying run in the bottom of the tenth inning of Game 3, which the Braves went on to win in twelve innings giving them a three games-to-none lead.[/fn] Whitted, who had started every game since September 8, played every inning of all four games in center field, never mind that the Athletics started three righties.

REVOLUTION, EVOLUTION, OR EVOLUTIONARY REVOLUTION?

George Stallings’s undeniable genius in using his outfielders in a platoon system to surprisingly win it all in 1914 is generally considered a revolutionary advance in managerial strategy.[fn]See, for example, Bill James’s discussion in The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers, 47.[/fn] Although the term itself did not come into vogue until much later, “platooning” upended the prevailing wisdom that, barring injuries or poor performance, seven of the eight position players in the starting lineup should be the same from day-to-day (the understandable exception being inevitably banged-up catchers) and, for that matter, mostly play every inning of every game.[fn]According to Robert W. Creamer in Stengel: His Life and Times (Simon & Schuster, 1984), his authoritative biography of Casey Stengel, who popularized platooning when he managed the Yankees in the 1950s, the term “platooning” was first used (“as far as I can determine”) by New York Herald Tribune sportswriter Harold Rosenthal “to describe what Stengel was doing.” (228).[/fn]

The bench players rounding out big league rosters were there more for emergencies to substitute for an injured regular, to give a regular an occasional day of rest, or to take over if the incumbent at a position was ineffective. Teams that were generally favored by the baseball gods with good health and few injuries could rely on no more than ten or eleven position players who would receive nearly all of the playing time—four regular infielders, three regular outfielders, typically two catchers, and one or two versatile bench players to fill in wherever necessary.

To the extent teams had platooned at all before Stallings’s Braves, it was almost exclusively at catcher, because of the wear and tear inherent in playing their position in an era before catchers’ armor offered much in the way of protection. Virtually all teams until late in the first decade of the century used at least two catchers interchangeably, although both were usually right-handed batters. In 1903 and 1904, the Giants’ left-handed batting Jack Warner and right-handed batting Frank Bowerman gave John McGraw the luxury of a true lefty-righty platoon behind the plate.

Because of the compelling narrative of the Miracle Braves, 1914 historically is considered the baseline year for platooning. But had the Braves not made their miracle run, or perhaps even fallen just short, would Stallings’s platoon stratagem have even been noticed? This seems a fair question because, while starting lineup data are not yet available before 1914, Retrosheet data on position games played suggest George Stallings also platooned at all three outfield positions the previous year, his first as Braves manager. Connolly played 124 games in left field in 1913, with right-handed batters accounting for all but four of the other 49 position games played in left.

Coincidentally, left-handed pitchers started 40 games against the Braves that year, according to Retrosheet, ten more than the total number of games Connolly did not play—some or all of which could have been after a right-hander was brought in to replace the left-handed starting pitcher. Mann played 103 games for Stallings in center, but the left-handed batting Guy Zinn played 34 games at the position in the 45 games left on Boston’s schedule after his contract was bought from Double-A Rochester in mid-August. The 11 games he did not play corresponds almost exactly to the 12 when opposing teams started a southpaw against the Braves.[fn]Zinn’s contract was purchased on August 18.[/fn] And after veteran lefty John Titus broke his leg in July, Stallings appears to have platooned the left-handed Tommy Griffith with the right-handed veteran Bris Lord in right field, each playing 35 games at that position.

Notwithstanding that Stallings’s outfield rotation to gain a competitive platoon advantage against opposing pitchers was a key element underwriting the 1914 Braves’ unexpected championship, there was surprisingly little if any commentary at the time about his insightful strategy. None of the articles in Baseball Magazine in 1913 (if Stallings did indeed platoon that year, as seems likely), 1914, or 1915 mentioned it. The magazine’s feature on the World Series praised Stallings for winning it all with “a club of green players and discards from other clubs” and “with one of the strangest assortments of misfit players we ever saw gathered together under one banner,” and observed that Stallings had “performed the impossible” with a team that “had no license” to win either the pennant or the World Series, but did not say how exactly he did it.[fn]F.C. Lane, “Where the Dope Went Wrong,” Baseball Magazine (December 1914): 16–17.[/fn]

The closest any article came was the one on Joe Connolly, which after noting that Stallings did not pencil him into the lineup in games started by left-handers despite his supposedly having hit southpaws well in his minor league days, said: “We will, however, not attempt to criticize the methods of Stallings, as his record speaks for itself.”[fn]Johnston, “Good Natured Joe Connolly,” Baseball Magazine (February 1915): 27.[/fn] Stallings, in an extensive interview for that publication recounting his team’s tribulations and ultimate triumphs in 1914, said nothing about platooning or how he used his outfielders. The closest he came to that point was to give what has become the now-standard trope about it being a team effort: “Ours is no one-man team.”[fn]F.C. Lane, “The Miracle Man,” Baseball Magazine (February 1915): 64. Lane also made no reference in the article to Stallings’s outfield rotation.[/fn]

So was Stallings’s failure to mention his strategy on platooning an effort to keep a baseball secret to himself? That hardly seems likely, since any professional manager would surely notice, and indeed by the end of the decade, platooning was widely practiced. Or was it perhaps that Stallings wanted to avoid calling attention to the fact that his outfielders, collectively and individually (with the possible exception of Connolly) were not very good? After all, even in the deadball era, outfielders were expected to be major contributors to their teams’ offense, and no matter Stallings’s success in masking his outfield deficiencies through the art of platooning, the preference would always be for outfielders who could hit well enough to be in the starting lineup on a daily basis regardless of the pitcher.

In this regard, it should be noted that, despite knocking off the two best teams in baseball—the Giants and Athletics—Stallings did not stand pat with his team that offseason. Instead, he moved to bolster the Braves’ outfield offense by trading for Philadelphia Phillies slugger Sherry Magee, giving up Whitted, Dugey, and lots of cash in the exchange. An 11-year veteran, the 30-year old Magee had led the National League in hits, doubles, and RBIs in 1914 while crashing 15 home runs—the third most in baseball—and batting .314.

Although he hit only two home runs on the season on account of the Braves’ home field being far more expansive that the Phillies’ Baker Bowl, Magee did in fact provide a stable, daily, potent presence in the Braves outfield in 1915, playing in all but one game.[fn]The Braves played at Fenway Park, home to the Red Sox, for most of 1915 until their new ballpark—Braves Field—was ready for baseball in mid-August.[/fn] With a 4.8 WAR, Magee turned out to be the best position player on the 1915 Braves. Stallings continued to platoon at two outfield positions, with Connolly the left-handed fixture in his left field rotation and Moran the same in his right.

Or perhaps Stallings did not talk about his philosophy on platooning in his remarks to Baseball Magazine because it seemed to him so intuitively obvious that he didn’t think it needed mentioning. While he deserves credit for undeniable genius in using his outfielders in a platoon system, rotating two players at the same position was not so much unheard of before this time as not practiced. Managers and players had long had an inherent understanding that a batter hitting from the opposite side of what hand the pitcher throws has a better visual and reaction-time advantage, and left-handed batters (same as today) seemed to have a particularly difficult time against southpaw pitchers.

An argument can be made, therefore, that platooning two players (or sometimes more, as Stallings did in 1914) at the same position to take advantage of a right-handed/left-handed split became institutionalized by the collective wisdom of managers observing and learning from each other, and becoming more strategic in their thinking. If so, the foundation for Stallings’s strategic innovation of platooning in his starting lineup was his appreciation of the value of position player substitutions that managers had been increasingly making to gain a batter-pitcher advantage at critical junctures during games.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, managers rarely replaced anyone in the starting lineup during a game. Even pinch hitting was rare because pitchers for the most part finished what they started and typically would remain in the game in the late innings of close ball games even if they were losing. By the end of the first decade, however, managers had begun to use their bench more strategically during games. Giants manager John McGraw led this innovation, being much more inclined to pinch hit and/or pinch run at a key moment of the game, which often required a defensive replacement.[fn]New York Giants star pitcher Christy Mathewson (or rather, Mathewson’s ghost writer) wrote about McGraw’s astute judgment in making these kinds of decisions during games in his 1912 book, Pitching in a Pinch: Baseball From the Inside (Penguin Classic, 2013).[/fn]

By 1910 McGraw was making more than 100 in-game position player substitutions during the season, more than double the league average, which had been steadily increasing not only because of McGraw, but other teams following suit. In his first year managing Boston in 1913, Stallings replaced a position player in the field 116 times, 57 in the outfield, eclipsing McGraw’s 113 substitutions that year.[fn]The number of in-game position player substitutions made in the field in any given season is the difference between the total number of position games by a team’s players and the total number of position games started as calculated by the number of games played by the team multiplied by eight fielding positions. Pitchers are not included in this calculation. Neither are pinch hitters who did not appear in the field. For example, position players on the 1913 Braves combined for 1,348 games, while the 154 games the Braves played that season, multiplied by the eight fielding positions, total 1,232 position games started. The 116-game difference is the number of defensive changes Stallings made during the season, either after having used a pinch hitter or pinch runner; to insert a superior defensive player into the game; or to replace a player who got hurt. These data can be found for each season on Retrosheet.[/fn] Given that he made an average of only 51 in-game substitutions when he managed the New York Highlanders in 1909 and 1910, which was right at the league average, Stallings’s adoption of the strategy was almost certainly to compensate for an offensively weak team. The 1913 Braves had the second-lowest team offensive WAR in the National League.

Once he became manager in Boston, Stallings took the tactical advantages of position player substitutions to their logical conclusion. If replacing a position player at a critical moment during the game was a savvy managerial move to gain a platoon advantage against the opposing pitcher (whether the starter or a reliever), then it made sense to seek such an advantage at a position of weakness—which, for Stallings, was his entire outfield—from the beginning of the game by choosing his starter based on the throwing arm of the starting pitcher.

Without specifically mentioning platooning, Stallings is said to have replied when asked about his approach to managing, “Play the percentages,” which is of course what platooning is intended to do.[fn]Stallings as quoted by Kaese, 139.[/fn] Because managers were already “playing the percentages” to give their team the best possible comparative batter-pitcher advantages at key moments within games, the strategy of platooning can be seen on its merits alone as arguably less revolutionary than evolutionary. Indeed, Stallings appears not to have been alone among managers in adopting platooning as a strategy as early as 1914 (if not earlier). The Cardinals were able to achieve a platoon advantage of at least four players in the starting lineup in over 90 percent of their games because, in addition to two switch-hitters and a left-handed right fielder, player-manager Miller Huggins had an outfield platoon that included the left-handed Walton Cruise paired with the right-handed Ted Cather (until he was traded to the Braves) and then Joe Riggert.

And then there was John McGraw. Even though Stallings’s epiphany about platooning in the starting line-up almost certainly occurred to McGraw, he does not appear to have done so (except at catcher) until 1914—the year Stallings had such success with the strategy, and quite likely a year after Stallings first used the strategy—when he paired off rookie left-handed hitting outfielder Dave Robertson with the right-handed veterans Fred Snodgrass and Red Murray. After being called up by McGraw in late May, Robertson started 68 games for the Giants in right or left field—not a single one against southpaws. McGraw, however, still seemed to prefer a set lineup and typically always had players for all eight non-pitching positions he judged good enough to deserve taking the field every game. Robertson was a regular each of the next two seasons, but was reduced to a platoon role again in September 1917—this time with former US Olympian Jim Thorpe—when he had difficulty hitting left-handers.[fn]There is an interesting historical footnote on the machinations of both platooning and position player substitutions. In the 1917 World Series, which the Chicago White Sox won in six games, McGraw started Robertson in all five of the games the White Sox started a right-hander. In the one game McGraw wrote Thorpe into the starting lineup—Game Five, when southpaw Reb Russell took the mound for Chicago—the Giants’ manager sent Robertson up to pinch hit for him in the very first inning because Russell, failing to get a single out, had already been replaced by a right-handed reliever. McGraw’s move worked as pinch hitter Robertson singled to drive in a run—one of his 11 hits on his way to a .500 batting average in the World Series—and remained in the game in right field. Since the Giants were the road team and this happened in the top of the first, Thorpe did not even get the chance to play in the field.[/fn] It was not until the 1920s that McGraw became baseball’s leading practitioner of platooning in his starting lineup.

That more teams would pick up on the advantages of platooning was likely inevitable, an evolutionary outgrowth, especially for managers who like Stallings did not have eight position players they felt comfortable starting every day, but had the Braves not won it all in 1914, the concept would probably have remained relatively obscure until some team did win using a platoon system. What was revolutionary was how quickly other teams adopted the strategy after 1914. The Braves’ success in coming from far behind to win the pennant and then take out the powerful Athletics ratified platooning as a road to victory. And thus did George Stallings become the historical midwife of the strategy.

CATCHING FIRE

While Stallings’ outfield platoon in 1914 was really making a virtue out of a necessity, other managers took notice of its advantages. By the 1920s, platooning was widespread in major league baseball, and most teams had a tandem lefty-righty couple playing at least one position. Using designated players interchangeably allowed managers to take advantage of their comparative strengths and, perhaps more importantly, to mitigate their weaknesses (such as an inability to hit lefties or to play every day of the long hot summer).

It should be noted, however, that the overwhelming majority of lefty-righty position platoons were in the outfield. With the exception of first base, platooning in the infield was relatively uncommon—and very rare in the middle infield positions—both because most infielders in that era were right-handed batters, and because managers desired daily stability at such premium defensive skill positions.

Platooning was an obvious strategy for mediocre or bad teams to try to compensate for the weaknesses of individual players. While it was not intuitively obvious that managers of very good teams would find much merit in platooning, even if they nonetheless sought platoon advantages in the course of a game, managers with much stronger cohorts of players than Stallings had with the Braves were quick to see the value of platooning at a position of relative weakness in their lineup—and every team had at least one. Starting with Stallings’s 1914 Braves, every World Series until 1926 featured at least one team that used at least one position player platoon during the regular season. They included all four of McGraw’s pennant-winning teams from 1921 to 1924.

Unlike Stallings, who had more of an inchoate mix-and-match philosophy for platooning in his outfield, most managers who platooned relied on a designated tandem pair who split the position between them. This seems an important point: as with a set lineup, most managers who platooned required a semblance of stability in which they relied on certain pairs of players at selected positions and players understood their roles in the scheme. Of course, players’ understanding their role is not the same as agreeing with such a division of their playing time. As Bill James has suggested, the fact that good players understandably resented the implication they lacked the ability to be everyday players helped to doom the widespread use of position platoons as a line-up strategy by the end of the 1920s.[fn]James, 89.[/fn] The same downward trend was also true for in-game position player substitutions. It would not be until after the Second World War that position player game substitutions and platooning would make a comeback. The perpetrator: one Mr. Casey Stengel.

- Appendix: To see the full information and methodology regarding starting line-up platoons, see the Appendix online by clicking here.

BRYAN SODERHOLM-DIFATTE lives and works near Washington, DC, and is devoted to the study of baseball history. He is a regular contributor to SABR’s journals and publications and has presented at several SABR national conferences. He is also writer of the blog Baseball Historical Insight.

Originally published: January 22, 2015. Last Updated: January 22, 2015.