Pedro Formental

An injury brought Pedro Formental north to make his debut in Organized Baseball. [fn]Billed as a 36-year-old rookie,[/fn] Formental was already a legend in Mexico and his native Cuba for his flamboyant manner at the plate, in the field, and in life at large. Still, he has earned little notice in the world of English-speaking baseball when ordered by Cuban Sugar Kings management to report to Rochester, New York, for an International League Doubleheader on June 29, 1954.

The day before, Angel Scull had suffered a fractured cheekbone in a collision with Rochester’s Joe Cunningham and the Havana Sugar Kings outfielder would be out for two to three weeks. The Cuban team signed Formental with instructions to arrive in time for the next day’s games.

The left-handed slugger, who was actually 35, was placed in right field and penciled in seventh in the lineup. He faced Rochester left-hander Niles Jordan in the opening twilight game, during which he displayed the hitting prowess that made him so feared a batter in Latin America.

Formental stroked two singles and a three-run homer, as well as a sacrifice fly, to knock in seven of Havana’s eight runs in an 8-5 victory in seven innings. He went 0-for-4 in the night game, a 5-3 win in 10 innings. Yet he sacrificed home another run, giving him an astonishing eight runs batted in in the doubleheader, a remarkable achievement even for a one-time Cuban winter league batting champion.

The Havana-based Sugar Kings (formally known as the Cuban Sugar Kings but usually carrying only the city name in the popular press) enjoyed a winning streak following his call-up, [fn]winning 14 of 22 games “after the ageless rookie, Pedro Formental, began striking long and timely blows,” according to The Sporting News.[/fn]

Formental’s sojourn in the International League would last just 204 games over two seasons, during which he showed flashes of the power and exuberance that had made him so popular a figure in his homeland. Known there as Perucho, a common nickname for Pedro, he also gained a nickname for his shameless bragging. He had so certainly and so often declared himself to be a .300 hitter that he was said to repeat the phrase like a perico (parrot). He eagerly adopted the moniker and began declaring, “A mí me llaman Perico 300” (“They call me Perico 300”).

Formental’s reputation was that of a classic baseball “hot dog.” Exasperated by his dramatic catches on even routine flies, knowledgeable Cuban fans declared him to be a postalita, a “little postcard,” a phrase used to describe flamboyant, showy players. His histrionics somewhat masked his ability to make spectacular catches. Whatever his flair in the field, he was a dominant and feared hitter at the plate. The major leaguers who played with and against him in Cuba were deeply impressed by his power. [fn]Bill Virdon considered Formental the “Babe Ruth of Cuba.”[/fn]

“Formental was the best thing the Cuban league had going in the years immediately after the world war — at least in terms of a heav(y)-hitting offensive star,” Peter C. Bjarkman writes in his A History of Cuban Baseball. [fn]The left-handed slugger was “the most luminous local star,” Bjarkman added, “who put up the biggest numbers and most talked-about individual performances.”[/fn]

The 5-foot-11, 190-pound slugger captured the imagination both of Cuban youth and of nationalist-minded Cuban fans, which is to say almost all of them.

“A dark mulatto with a pencil-thin mustache, Formental was a flashy dresser, and a devotee of cock fighting, which endeared him to the macho crowd in Cuba,” Roberto González Echevarría wrote in The Pride of Havana. “In fact, Formental seemed to be the quintessential criollo man. [fn]Brave, a lady-killer, and reputed to carry a gun, he played with flair, often making spectacular catches in center field (but also prone to dropping an easy one).”[/fn]

In the hothouse of Cuban politics, which roiled with tension and violence throughout the previous century, Formental was seen as a loyal follower of Fulgencio Batista, the dictator who fled the island on New Year’s Day in 1959. The deposed strongman lived in exile in Spain and Portugal, where he was later reportedly sought out by Formental, who by then was without money or means of support. Little is known about what aid the exiled dictator may have actually provided to his former enthusiastic supporter.

Pedro Roberto Formental Sarduy was born to Catalina and Tomas on April 17, 1919, in Baguanos, a sugar-mill town in Cuba’s Oriente (Eastern) province, in an area now designated as part of Holguin province. As an adult, he would name Banes, a town about 25 miles to the northeast, as his hometown. When the boy was 14, his region was embroiled in political strife, as sugar workers protested terrible conditions with a series of general strikes, including the raising of a homemade red revolutionary flag atop the mill at his birthplace. (At another nearby mill, striking workers sang the “Internationale,” the communist anthem, and played a baseball game.) When embattled and highly unpopular President Gerardo Machado fled the island in the wake of such fomenting rebellion, the door would be flung open for the ambitious Fulgencio Batista. A month after Machado’s flight, Batista, an army sergeant who had been born in Banes, led an army uprising known as the Revolt of the Sergeants. Its success launched Batista on a political career that would see him serve two terms as president — the first as an elected populist with progressive programs and the second following a coup after which he amassed a great personal fortune while ruling as a dictator.

Formental launched his ballplaying career with the local Central Baguanos team, where he was brought to the attention of the owner of a semipro team in Havana in 1941. He was soon signed by the Cienfuegos Elefantes of the Cuban professional winter league. He was one of several black stars on the team, which led a radio announcer to dub them the Petroleros, a crude and racist play on the Spanish word for crude oil, which also served as a slang for white men who sought sex with black women.

Formental spent three undistinguished seasons with the Elefantes, showing little of the power or speed that would make him such a threat with the Havana Reds for a decade. In his career Formental twice led the Cuban League in runs batted in (46 in 1951-52 and a record-tying 57 in 1952-53), runs scored (51 in 1949-50 and 47 in 1951-52), triples (six in 1943-44 and six again in 1946-47), walks (53 in 1950-51 and 50 in 1952-53), and home runs (eight in 1950-51 and nine in 1951-52). In 1949-50, his 99 hits led the league, as did his .336 average.

Formental played in three consecutive Caribbean Series with Cuba’s representative (the Habana Leones, also known as the Habana Reds), victor in the 1952 the tournament. [fn](Formental managed to hit a lone single in 16 at-bats, although he had two “sensational catches in center” to help save Tommy Fine’s no-hitter against Cerveceria Caracas, the Venezuelan champion.)[/fn] He led the tournament the following year with a superb .560 batting average, although the Reds squandered both his efforts and home-field advantage as Santurce of Puerto Rico won the title.

The outfielder was an all-seasons player. While he patrolled the outfield in his homeland in winter, he also dressed for teams in Mexico (Tampico in 1943, Vera Cruz in 1944 and ’45, San Luis in 1946), the Dominican Republic (Águilas Cibaeñas in 1953), Venezuela (Pampero in 1955-56), and the United States (Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League from 1947 to ’51). He ultimately spent parts of two seasons (1954 and ’55) with the Havana Sugar Kings of the International League. In Mexico he once recorded 10 consecutive hits, played in the all-star game, and earned the nickname Pato (Duck). (Pato is a slur commonly directed at gay men and may have referred to Formental’s flamboyant play. It may have been used as a reference to his ceaseless braggadocio. Or it may have been a prank pulled on Formental by another player using an unwitting non-Latino reporter.)

Whatever his exploits on the field, Formental earned a reputation as a proud, defiant, mercurial character. “Formental would come to the ballpark with a gun stuck inside the front of his pants,” said Dick Schofield, his teammate in Havana. [fn]“In the clubhouse, Formental would take the gun and knock the clips of bullets out of the gun. He would put the bullets in a bag with his watch and money and billfold and rings. He would throw the gun on top of his locker. After the game, he would pop the clip of bullets back in the gun.”[/fn]

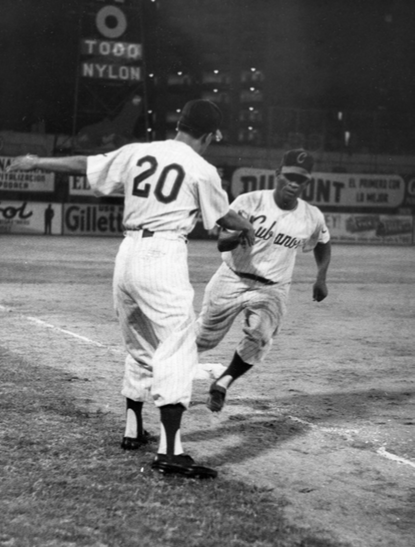

Having a firearm at close proximity to the field nearly ended in tragedy. In a game against Cienfuegos, formental in cuban league action at havana’s la tropical Park his old team, Formental was beaned twice by Jim Melton. As he took first base after the second drilling, he pointed his forefinger and cocked his thumb as though shooting a gun. After the game, Formental returned to the clubhouse, where he was seen loading his gun with anger on his face. Happily, Cuban teammates talked him out of confronting the opposition pitcher.

Another popular but likely apocryphal story told about Formental involves his being refused service in a Dallas restaurant on account of the color of his skin. The Memphis Red Sox player angrily confronted a Jim Crow convention he felt did not apply to him as a foreigner by flashing his Cuban passport and insisting on being served.

The outfielder played in 204 games over two seasons with the Triple-A Sugar Kings, hitting .293 in both campaigns. He smacked an impressive 13 homers in just 77 games after being called up in 1954, adding another eight the following year over 127 games.

He had rejected an earlier opportunity to make his debut in Organized Baseball. In 1951 the Ottawa Giants purchased Formental’s contract from the Memphis Red Sox, but the outfielder refused to report to the Canadian club and the deal was canceled. A few more seasons in the International League closer to his prime would likely have generated more interest in the slugging outfielder.

Formental retired from Cuban baseball tied with Alejandro Crespo as all-time RBI leader with 362 (soon surpassed by Ray Noble’s 372). He was also the career leader in runs scored with 431 and was the all-time home-run champion with 54.

A final splash in Formental’s athletic career came as he wound up his playing days. Late in 1955, while playing in Venezuela, he won a $21,000 prize in a Cuban lottery. Good fortune was eventually to be overwhelmed by political developments in his homeland.

The collapse of the Batista regime meant Formental would have to leave his island homeland, as he was closely identified with the dictator, even having campaigned for his short-lived United Action Party (Partido de Acción Unida) before his Oriente ally took power in a coup. Formental, once the toast of Cuban baseball and cheered by a generation of boys, became a lost and mysterious figure in the final years of his life. González Echevarría tried without success to track down his boyhood hero while researching his book on the history of Cuban baseball. He discovered that Formental had lived in Spain with former manager Clemente “Sungo” Carrera after the revolution.

“They subsisted on public charity provided by other Cuban exiles and the Spanish government,” the author writes. “One afternoon, when all they had left was a baseball glove they planned to pawn, they were sitting at an outdoor cafe, pondering what to do next. There they were spotted by movie producer Samuel Bronston, in Spain to make one of his epic films. He approached the two Cuban blacks and told them he needed extras of their color for a project he was working on. He hired them on the spot, and both worked as voodoo priests in one film, and later as extras in battle scenes of The Fall of the Roman Empire. Once these jobs were over, Formental went to see (exiled Cuban poet Gastón) Baquero, who suggested he go seek Batista’s help in Estoril, Portugal, where the former sergeant had a home. The exiled (dictator) was, after all, their compatriot and both the poet and the player had been his followers. [fn]Formental showed up at Batista’s complex, but the guards refused to let him in, whereupon he started to shout at the top of his lungs, ‘Batista, Perico Formental is here!’ Eventually Batista emerged, let him in, and gave him money to buy passage to the United States.”[/fn]

Formental wound up in Chicago, where he is believed to have earned his living as a babalao, an Afro-Cuban priest. He later moved to Cleveland, where, in 1985 the 64-year-old retired ballplayer married Ruth (née Wilbershied) Balluff, a woman 27 years his junior. (His first name is listed as Fedro in online documents.) The flashy outfielder found anonymity in the second half of his life. His death at 12:35 A.M. on September 15, 1992, in a hospital in Warrensville Heights, Ohio, went unnoticed by fans or press.

Formental was elected to the hall of fame of the Miami-based Federation of Cuban Professional Baseball Players in Exile in 1972. He was named to the Caribbean Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

This biography originally appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Full Name

Pedro Roberto Formental Sarduy

Born

April 17, 1919 at Baguanos, Oriente (CU)

Died

September 15, 1992 at Warrensville Heights, OH (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.