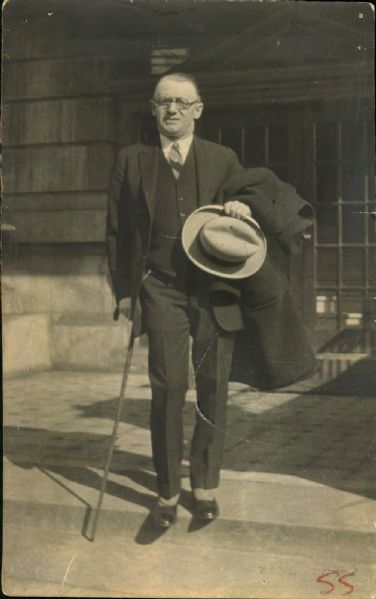

Carl Zork

In announcing the March 1921 indictments of the players and gamblers involved in the Black Sox Scandal, Cook County (Illinois) State’s Attorney Robert Crowe announced that the World Series fix originated in St. Louis, specifically with Carl Zork and Benjamin Franklin, rather than in Boston and New York by the Eastern clique of Arnold Rothstein, Sport Sullivan, and Abe Attell.

In announcing the March 1921 indictments of the players and gamblers involved in the Black Sox Scandal, Cook County (Illinois) State’s Attorney Robert Crowe announced that the World Series fix originated in St. Louis, specifically with Carl Zork and Benjamin Franklin, rather than in Boston and New York by the Eastern clique of Arnold Rothstein, Sport Sullivan, and Abe Attell.

The early investigations of American League President Ban Johnson centered on St. Louis, as disappointed gamblers there fingered the Midwesterners.1Yet despite this focus on the St. Louis connection, relatively little has been done on the lives of the gamblers involved.

It is impossible to properly assess the validity of the “Midwestern” thesis unless we know more about the principals. Des Moines gambler David Zelcer’s involvement was covered in an excellent article by Ralph Christian on the Des Moines connection in SABR’s Black Sox Scandal Research Committee June 2013 newsletter.2 This article will try to flesh out the life of Carl Zork.

Carl T. Zork was born on June 9, 1878, at the family home, 1153 N. 6th Street in St. Louis, the son of German immigrants Simon and Clara (Gogel) Zork.3 Simon Zork, a respected clothing merchant, served as secretary of St. Louis’s United Hebrew Congregation. Carl married Sadie Twomey in Chicago in 1907.

Prior to 1920, Zork worked in various branches of the garment industry. In 1910 he was manager of the A.S. Rosenthal Company’s St. Louis branch, specializing in silk clothing.4 At the time of the 1919 World Series, Zork was (ostensibly) president of the Supreme Waist Company, a St. Louis-based shirtwaist firm. One Joseph Evans, vice president of the firm, may have been a relative of a New York fixer, the Russian-born and St. Louis-raised Nat Evans.5 Black Sox grand jury witness Harry Redmon later testified that Zork “is in the silk business, supposed to be, but he does more gambling I guess than anything else. …”

Carl Zork had a long and close relationship with boxer/gambler Abe Attell. In 1904 Zork and Abe’s brother Monte attended one of Abe’s fights. In 1907 Zork tried to arrange a fight between Attell and Jack Sullivan.6 Zork promoted Attell’s 1912 fight with little-known St. Louis boxer Oliver Kirk, a fight the sporting press accused Attell of “tanking.” In the sixth round, “Attell, who had been stalling all along, threw up his hands” and told the crowd he was “all in.” A week later Attell had “his St. Louis friend, Carl Zork” retract the retirement statement. Collyer’s Eye, a small gambling publication that would go on to play an integral role in uncovering the 1919 World Series fix, later accused Zork of betting heavily on Kirk, then setting up a rematch that Attell easily won, Zork making money both times. Collyer’s Eye called the match “one of the rawest deals ever pulled in a prize ring.”7

Zork loved to bet on baseball, too, and on at least one occasion dabbled in game-fixing. In early 1919, St. Louis Cardinals first baseman Gene Paulette met with Zork and fellow St. Louis gambler Elmer Farrar. The wily duo supplied Paulette with cash and asked whether the player was willing to fix games. Later that year Paulette, now with the Phillies, wrote a letter to Farrar asking for $400, and hoping “Carl will let me have it. … I am in position to help him clean up in our next series with the Cardinals,” promising that he could get two other players to cooperate in game-fixing with him.8

According to several gamblers contacted during the Black Sox investigation, Zork (“a double-crosser, a fixing gambler”) and Farrar (a champion billiards player) “have been forming up different schemes to cheat people for several years,” with Farrar throwing matches and Zork cleaning up on betting against him.9 Later, new baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis came into possession of the Paulette-Farrar letter. Landis didn’t believe Paulette’s denial of wrongdoing, especially since Paulette admitted that he had accepted “loans” from Farrar that he never repaid. On March 24, 1921, Judge Landis banned Paulette from baseball, an action that would set a precedent for the subsequent bans of the Black Sox .10 Reacting to Paulette’s banishment, Zork admitted he knew Farrar, but claimed he “knew nothing about it [the fix].” He declined to offer further comment.11 Unfortunately for Black Sox history, the judge at the Black Sox trial prevented testimony about Zork’s fixing these earlier games.

Just before the 1919 Series, former St. Louis Browns player Joe Gedeon got word from his friend Swede Risberg that the Series fix was on. Gedeon promptly notified Carl Zork, which implies that Gedeon and Zork had had “dealings” prior to this. Zork later admitted that Gedeon had approached him to wager $1,000 on the Reds.

Zork denied knowing of the fix prior to Gedeon’s tip.12 That denial was corroborated by Sam Leavitt, Zork’s one-time friend and former attorney, who stated “he didn’t think Zork had any knowledge of the frame up” prior to Gedeon’s tip. Leavitt’s exculpatory words have added significance, as he was furious with Zork getting him to wager $2,000 on the Reds! According to Leavitt, Zork should be sent to prison “for all his crooked deeds.”13

When in March 1921 the Cook County Grand Jury indicted Zork, he reacted with amazement. “I cannot understand why I should have been indicted,” he protested. “I am absolutely innocent of complicity with throwing a ball game in the 1919 world’s series, or with the throwing of any ball game anywhere at any time.”

Rebutting Zork’s assertions of innocence, St. Louis theater owner Harry Redmon testified that he ran into Zork at the Morrison Hotel during the Series and that Zork “took all the credit for framing [the Series] up, that he was the cause of it all.” Zork told Redmon, “I’m the little red-haired fellow from St. Louis that was responsible for it all — and it didn’t cost me a cent.” Zork talked so loudly that Redmon cautioned him against being overheard, to which Zork replied “I don’t care, I got an alibi.” Redmon didn’t know if Zork was bragging or telling the truth.

Zork’s “alibi,” as it turned out, was a very public wager ON the White Sox, for $2,000, with Sport Sullivan, using the very respectable Al Herr of The Sporting News as stakeholder. Zork also boasted of fixing other games in 1919, “but the testimony in this regard was ordered stricken out.”14 One newspaper article says Zork bet $50,000 on the Series, and another article says he “cleaned up” tens of thousands of dollars.15

Zork’s attorney’s tried to get him excused from the trial, alleging that he was suffering from “melancholia” bordering on insanity. The trial judge, unimpressed, ordered that Zork be included. They needn’t have bothered. At the end of the trial, the only evidence implicating Zork was Harry Redmon’s, telling of Zork’s bragging. And to counter that, the defense had produced several character witnesses from St. Louis who testified to his good character, as well as witnesses who rebutted details of Redmon’s testimony.16

Trial judge Hugo Friend denied the defense’s motion to dismiss the charges against Zork, but warned: “There is so little evidence against these men [Zork, Buck Weaver, and Happy Felsch] that I doubt I would allow a guilty verdict to stand if it were brought in.” The judge felt that Redmon’s testimony did not sufficiently connect Zork with the conspiracy for which he was indicted, and which (according to trial testimony) was abandoned after Game Two, but rather with a subsequent conspiracy to throw games.17 The jury acquitted Zork, so the judge never had to set aside any verdict.

Zork’s reaction to the verdict reflected his amazement that he’d even been indicted: “I don’t know why they brought me up here. … I never knew any of the other defendants until I met them in court.” Technically, this statement may have been true.18

In his later years Zork worked as a salesman for the Meletio Sea Food Company in St. Louis. He died of heart disease in St. Louis on January 17, 1947. He is buried in that city’s Mt. Olive Cemetery.19

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on major online newspaper databases and the author’s article for the Black Sox Research Committee’s December 2014 newsletter.

Notes

1 See the Crowe announcement, reported by the Portland Oregonian, March 27, 1921. The Midwestern-origin thesis is followed by several historians. See David Pietrusza, Rothstein: The Life, Times and Murder of the Criminal Genius Who Fixed the 1919 World Series (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003); Ralph Christian, “The Des Moines Connection to the Black Sox Scandal,” Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, June 2013, 6-13; and Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2003). Susan Dellinger, Red Legs and Black Sox (Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2006), adds a new layer of involvement by the Levi brothers.

This biography of Carl Zork is based largely on Bruce S. Allardice, “The St. Louis Connection: Carl Zork and Ben Franklin,” Black Sox Research Committee Newsletter, vol. 6 No. 2 (December 2014), 11-14.

2 Christian, op cit., which can be found in the SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee’s June 2013 newsletter. These charges were aired early on. See “New Indictments Mean Fresh Drive on Conspirators Against Baseball,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1921.

3 Born within a block of Nat Evans’s home. As per the author’s article on Nat Evans (see Black Sox Research Committee Newsletter, June 2014, or the Evans biography at http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/83d52aa2), it seems quite likely that Evans and Zork grew up together and knew each other well.

4 1910 St. Louis Directory. Zork lived at the Washington Hotel.

5 This Evans (1880-1937) was the son of Russian-Jewish immigrant Moritz (Joseph) Evans of St. Louis. Moritz was the right age and background to be the brother of Julius Evans (Evenski), Nat Evans’s father.

6 “Simms Seeks bout with Fitzgerald,” St. Louis Republic, December 26, 1904. “Attell Is Willing to Meet Sullivan,” Los Angeles Herald, September 15, 1907. See “General News and Comment of Fighters and the Ring,” St. Louis Republic, March 27, 1904; “Prince and Zork Off for Fight,” St. Louis Republic, January 3, 1904, for more mentions of Zork and Attell.

7 “Attell Foxiest of all the Ring Champions,” Texas Railway Journal, vol. 7, No. 4 (April 1913), 16; “Abe Attell thinks St. Louis Is Easy,” New Orleans Times Picayune, December 8, 1912; “Identify St. Louis Gamblers Involved in Series Scandal,” Collyer’s Eye, October 9, 1920. However, veteran writer Sid Keener of the St. Louis Times thought the tanking charges absurd. See “Attell Made Fall Guy by Writer,” Ogden Evening Standard, December 5, 1912.

8 Paulette to “Friend Elmer,” August 7, 1919, Black Sox Scandal papers, Giamatti Library, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

9 Harry Redmon to Ban Johnson, March 25, 1921, Black Sox Scandal papers, Giamatti Library, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

10 Timothy Newman and Bruce Stuckman, “They Were Black Sox Long Before the 1919 World Series,” Base Ball, Spring 2012, 75-85; Daniel E. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In. A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), 164; Bill Lamb, biography of Gene Paulette, at http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/147b2f14; “New Indictments Mean Fresh Drive on Conspirators Against Baseball,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1921. Pietrusza’s Rothstein, 159, and Gene Carney’s Burying the Black Sox, 44, explore allegations that Zork had tried to fix earlier games, including the 1918 World Series, in conjunction with St. Louis mobster Kid Becker.

11 “Paulette Barred: Accepted ‘Loan’ from St. Louisian,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, March 25, 1921.

12 Zork’s October 27, 1920, reply, Black Sox papers, Chicago History Museum.

13 Al Herr to Ban Johnson, Black Sox Scandal papers, Giamatti Library, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

14 Redmon affidavit, Black Sox papers, Chicago History Museum. “Baseball Plot Confessions Gone,” New York Times, July 23, 1921.

15 Newman and Stuckman, op cit.; Christian, op cit, 9.

16 William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Co., 2013), 132.

17 “Weaver Plans Return to Game When Judge Indicates Acquittal,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 28, 1921.

18 “7 Players, Zork and Zelcer, Freed,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 3, 1921.

19 “Necrology,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1947; “Carl Zork Funeral Services to be at 2:30 p.m. Tomorrow,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, January 18, 1947; Missouri death certificate #3327, 1947. Surviving Carl was his second wife, Beatrice (Mathews) (b. 1897), and their son Earl (b. 1936).

Full Name

Carl T. Zork

Born

June 9, 1878 at St. Louis, MO (US)

Died

January 17, 1947 at St. Louis, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.