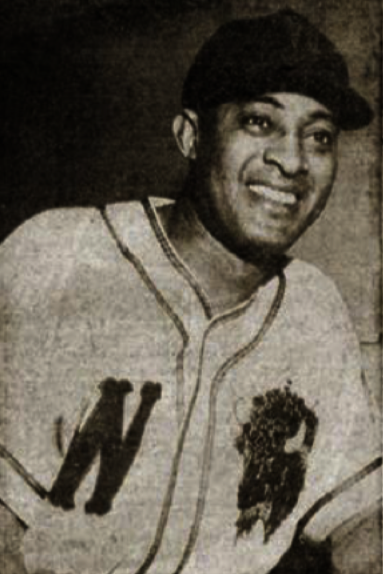

John Britton

John “Jack” Britton played professional baseball in four countries — the United States, Mexico, Canada, and Japan. He was even a pioneer in Japan, joining pitcher Jimmie Newberry as the first two African American ballplayers on a Japanese team. But he never had the opportunity to play in the major leagues.

John “Jack” Britton played professional baseball in four countries — the United States, Mexico, Canada, and Japan. He was even a pioneer in Japan, joining pitcher Jimmie Newberry as the first two African American ballplayers on a Japanese team. But he never had the opportunity to play in the major leagues.

Britton played in the Negro Leagues for more than 10 years, typically at third base. Unfortunately, we know far less than we would like to know regarding his life — not atypical for Negro League ballplayers.

He was born as John A. Britton Jr. in Mount Vernon, Georgia — the county seat of Montgomery County — on April 21, 1919. His father was, of course, John A. Britton. His mother is listed in Social Security Administration files as Tehnie Collins. Britton’s death certificate gives her name as Tempie Collins.

How and when Britton got started playing baseball eludes us so far, but he is said to have begun in 1940 with the Minnesota Gophers, described as “a minor black team.”1 His play there was said to have impressed Abe Saperstein of the Gophers, who recommended him to Cincinnati’s Ethiopian Clowns and to the Homestead Grays; he signed with the Clowns later in the year. Jim Riley writes, “While with the Clowns, he played shadow ball and engaged in a few of their comedy routines. The one best received by the fans involved his wig. He had a clean-shaven head, but wore a wig and, as part of a comedic routine, after a bad call by the umpire would take his hat off and throw it on the ground in mock anger while arguing the ump’s call, and then would take his wig off and do the same with it. Then he would pick the wig and hat back up and put them on this head. The crowds loved it.”2

John Britton batted left-handed but threw right-handed, stood 5-feet-8, and is listed at 160 pounds. And he had a shaved head.

Dick Clark and Larry Lester say he also played for the New Orleans-St. Louis Stars in 1940. Jim Riley has him with the Ethiopian Clowns from 1940 through 1942, though at least one news story had him still playing for the Gophers (though the geography had changed somewhat) along with Goose Tatum and others.3 In March 1943 the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph reported that “Johnny Britton, hard-hitting third-sacker of the St. Paul-Milwaukee Gophers has been signed by the Clowns for this year.”4 Tatum and King Tut were both on the 1943 Clowns team and, along with pitcher Edward “Peanuts Nyasses” Davis, were said to form a “triumvirate of buffoons unequaled in baseball funology.”5

In 1943 one unidentified author wrote, “Britton hit .389 for the 1943 Cincinnati Clowns and was traded to the Birmingham Black Barons for Hoss Walker. With Birmingham, Britton was a key player in the heart of the order, batting third for the next five years.”6 Jesse “Hoss” Walker had already been with the Black Barons since 1941, however, and played for Birmingham in the 1943 playoffs and World Series against Homestead, so one is left to wonder when the trade took place. Given the fluidity of player movement in those days, it is not at all impossible that Walker opened and closed the season with Birmingham but was traded to Cincinnati at some point during the season. Perhaps the trade was after the season. Newspaper articles in May and June of 1943 show Walker at shortstop for Birmingham and Britton with the Clowns.

When games were played, of course, in cities such as Dallas and New Orleans, newspapers noted, “Special sections will be provided for Negro and white fans” or “A large section of the Pel Stadium stands will be reserved for white patrons tonight.”7

In 1944 John Britton played for the Barons and is shown with a .338 batting average in 68 plate appearances with one homer and 11 RBIs.8 One suspects he played in more games than this, but records are unfortunately less than complete throughout Negro Leagues baseball. John Holway cited his average as .324, ranking him fifth among Negro American League batters.9 Holway may well have been citing an unattributed summary record in Britton’s Hall of Fame player file, which shows a .324 batting average over 259 at-bats in 65 games. The New Orleans Times-Picayune showed him at .327.10 Artie Wilson led the team in hitting.

The Kansas City Monarchs had beaten the Homestead Grays in the 1942 Negro World Series. The Barons had finished second in the Negro American League in 1941 and 1942. Now in 1948, it was Birmingham’s turn to take on the Grays, Negro National League champion for six consecutive years. The series went to the seventh game, but Homestead prevailed.

Both Wilson and Britton were among five Barons in an “auto smashup” just prior to the Series, but as of September 16 most were expected to play, though Tommy Sampson had a broken leg and hip.11 Britton was in fact unable to play, due to a dislocated left hand, and both shortstop Wilson and catcher Lloyd “Pepper” Bassett were forced to miss action.12

Lester “Buck” Lockett filled in for Britton at third base. Homestead took the first three games, but Birmingham shut out the Grays 6-0 in Game Four behind the pitching of Johnny Huber. The Grays won in five games, and then the two teams continued to play each other in a series of exhibition games. Britton was active again with the touring Black Barons team, which made it to California in October. He was with the team during the preseason and as late as the end of April, but then departed, taking a sojourn to Mexico.

He played for the Azules de Veracruz (Veracruz Blues) in Mexico City, not in the coastal city of Veracruz. The owner of the team was Jorge Pasquel, himself a native of Veracruz. Signing Britton was far from an aberration. In 1940 alone, Pasquel had signed 13 Negro League players for the Blues. Author John Virtue reports that “Many fans dubbed the Azules the Aquila Negra because it was the Veracruz team with more black players than any other team in Mexico.”13 Veracruz at one time or another featured six future residents of Cooperstown: Cool Papa Bell, Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, Martin Dihigo, John Gibson, and Willie Wells. In 1942 Monte Irvin and Roy Campanella played baseball in Mexico, as did many others over the years. Willie Wells had managed the Azules in 1944, and Ray Dandridge was the manager when Britton played for the team in 1945.

With Dandridge playing third base and batting .366, Britton didn’t get that much work. He played in 29 games for Veracruz, collecting 118 at-bats. He was 33-for-118, with four doubles and three triples as his extra-base hits. That gave him a .280 batting average and a .364 slugging percentage. He did not homer, but he scored 18 runs and drove in 10. He had a pair of stolen bases.14

Back with the Birmingham Black Barons, Britton appears to have gotten into 27 games in 1945, with a .333 batting average.15

Britton played very little in 1946 and 1947, according to currently available statistics, with only seven plate appearances in 1946 (he was 2-for-7 at the plate) and 28 in 1947 (with only 25 at-bats and a .160 batting average).

In 1948 Britton got into quite a few more games, with 141 plate appearances, 18 RBIs, and a .201 batting average. He played in the 1948 World Series against Homestead, walking and scoring the second Barons run in the eighth inning of their 3-2 loss in Game One. In Game Four’s 14-1 loss, it was Britton who grounded out for the final out of the game.

Britton started the 1949 season at third base with the Barons. After 58 games, in mid-September, Britton was batting .242. Final statistics have so far proven elusive. After the season Britton played on a Creole All-Stars team which played Jackie Robinson’s Major League All-Stars in an October 16 game at Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon Park. Don Newcombe pitched for the Major-League All-Stars and won, 15-4, but Britton was 2-for-4 in the game.16

Britton started the 1950 season with the Indianapolis Clowns and helped beat Birmingham in an April matchup, singling to drive in the first run of the game. In late May he was the lead man — scoring on the play — as the Clowns pulled off a triple play against the Barons during a Negro American League game in Chattanooga.17

By the end of May 1950, Britton had headed north of the border, to Canada, where he played very briefly for the Elmwood Giants, but primarily with the Winnipeg Buffalos.18 Syd Pollock of the Indianapolis Clowns said Britton had jumped his NAL contract, but that he’d be willing to accept a cash settlement from the Buffalos.19 In the May 27 game against the Brandon Greys, hitting into the wind, “John Britton, hard-slugging third sacker for the Buffs, powered a tremendous home run onto the roof of the Amphitheatre to open the seventh.”20 He also had two singles in the game, and was singled out by the Winnipeg Free Press for his fielding. He had a few three-hit games, on August 5 a triple and two doubles, and a four-hit game on the 24th. Barry Swanton in his book on the Mandak (Manitoba-Dakota) League reports that Britton batted .328 with the one home run and 26 RBIs. Jimmie Newberry and Leon Day both pitched for Winnipeg. The next year, 1951, Britton hit over .300 again, batting .310 with 3 homers and 40 RBIs for the Elmwood Giants. (Elmwood was a neighborhood in Winnipeg.)21

Having played in the United States, Mexico, and now Canada, what was Britton’s next move?

On April 28, 1952, the occupation of Japan officially ended and Japan was again declared independent. That same day Bill Veeck and the St. Louis Browns sent Britton and pitcher Jim Newberry to the Hankyu Braves. The Associated Press story announcing the arrangement is somewhat amusing and informative and worth quoting at length:

Bill Veeck and his St. Louis Browns, who always welcome festive occasions, today marked the return of Japanese independence by sending two farm club ball players to Japanese professional baseball.

This marks the first time in history American ball players have been loaned to clubs outside the Continental United States.

Both of the lend-lease players are Negroes –third baseman John Britton, Jr., and pitcher James Newberry, a curve-balling right hander.

Final arrangements for sending the pair to Japan were completed by Abe Saperstein, owner-coach of the Harlem Globetrotters, and a stockholder in the new Brownies. Britton and Newberry were scheduled to leave Chicago late today for the plane hop to Japan.

They are on loan to the Hankyu Braves of the Japanese Pacific League. The club plays in Nishinomiya Stadium at Osaka, about 300 miles south of Tokyo.

They’ll be the first Negro players in Japanese baseball.

Explaining the move timed with today’s unveiling of an independent Japan, Veeck said: “As Japan gains its independence as the world’s newest democracy, we of the St. Louis Browns are happy to aid the mutual relations between the United States and Japan by sending two of our American ball players to the Japanese pro leagues. In Japan, as well as in America, baseball is the national game, and we feel that this gesture on the part of American baseball will go a long way toward cementing good relations with the Japanese.22

A photo of Britton, Saperstein, and Newberry ran in Jet magazine on May 15.23

One might wonder why a Japanese team would be named the Braves. Before the Second World War, the Hankyu baseball team was established in 1936 by Ichizo Kobayashi, the founder of Hankyu Railways Group. The team’s name was “Hankyu-Gun” (“Gun” means military troop in Japanese), and this name went through until 1946. Perhaps needless to say, the idea of a baseball team bearing such a name was not appropriate in the immediate aftermath of the war.

In fact, all the teams were “-Gun” before the war’s end, and the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers suggested a change in name.

In 1947, perhaps with the Chicago Cubs in mind, the Hankyu team changed its name to the Hankyu Bears. As Tom Yamamoto explained, the team unfortunately went on a losing streak right at the start of the season and some felt the name was another poor association, since in financial circles a bear market indicates one of rapidly falling prices. They decided to appeal to the public for suggestions. The name Braves was selected and the person who had submitted the winning suggestion explained that he had had the Boston Braves team in mind.

The season was already under way when Britton and Newberry arrived. In their first game for Hankyu, at Korakuen Stadium on May 7, 1952, Britton was 2-for-4 with a triple against the Mainichi Orions. He tried to steal home, but was thrown out at the plate. Jimmie Newberry started and went five innings, but the game was lost, 3-2, the three runs attributed to Newberry’s reliever, Yoshio Tempo. The winning pitcher for Mainichi was a Nikkei Nisei from Hawaii, Masato Morita. Britton, who wore number 8, was said to have made good defensive plays as the third baseman, backing up the pitcher and other infielders well.

Statistics show that Britton appeared in 78 games, batting .316 (seventh in Pacific League play) with 2 homers and 35 RBIs. We have learned since that foreigners arriving in Japan often have difficulty adjusting to Japanese pitching. Britton did so rather quickly and struck out only 12 times in 332 plate appearances.

Helping facilitate Britton’s welcome was manager Shinji Hamasaki, who had seen African American baseball players in his youth, finding them very friendly during a 1927 barnstorming tour of Japan. It was apparently he who requested that Hankyu sign some of the black ballplayers.

Britton was sufficiently impressive that he was named to the All-Star team, the first foreign player named to an All-Star team. The Braves finished fifth in what was that year a seven-team league, and not having made the top four, their season ended before any postseason play. Britton and Newberry returned to America on September 25.

Britton returned to Japan on February 13, 1953, and played a full season for the Braves, batting .276 with 60 RBIs. Still an exceptionally good contact hitter, he struck out only 13 times in 448 plate appearances. Former Negro Leaguers Larry Raines and Rufus Gaines were also on the Braves in 1953. The Braves finished in second place. Manager Shinji Hamasaki resigned, having not won the championship.

The season over, Britton once more returned to the United States. His professional baseball career as a regular was over. He still cropped up from time to time playing baseball. In Springfield, Massachusetts, he is found in June 1954 playing with the Harlem Globetrotters baseball team (headlined by Satchel Paige, though Paige was a no-show for this game), beating the House of David team, 9-6, Britton’s third-inning single having contributed to the win.24

After this point, Britton is not easily found in a search of online newspapers.

In June 1989 a reunion of Negro Leaguers was held in Atlanta and Britton was among them. An Associated Press photograph accompanied the story in some newspapers; the caption in the Augusta Chronicle read: “Former Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe checks out dome of John Britton, who played for Birmingham Barons in Negro League.”25 Britton’s bald dome reminds one of his shaved-head antics with the Ethiopian Clowns.

The last 12 years of his life he had lived in Chicago and worked as a freight loader for Lifschultz Freight Lines.

Britton was being treated for prostate cancer at Oak Forest Hospital in Bremen Township, Oak Forest, Cook County, Illinois, when he died on December 2, 1990, of an acute myocardial infarction. Oak Forest is a city about 24 miles south/southwest of Chicago. He was survived by his wife, the former Louise Paige. He is buried at Oak Woods Cemetery on Chicago’s South Side.

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Many people were very helpful in gathering information for this biography. Baseball records had not recorded the place of his death or burial, but SABR member David J. Holmes secured his death certificate from the Cook County Clerk. Terry Bohn helped with leads and information on the Man-Dak League years of 1950 and 1951.

Very helpful as well were Tomotada “Tom” Yamamoto and Ichiro Shinohara of SABR’s Tokyo Chapter, and Dr. Virgilio Partida, SABR member from Mexico, and Daigo Fujiwara of SABR Boston.

Notes

1 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/John_Britton.

2 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 111. Riley is also the source for the Abe Saperstein story.

3 “Ace First Sacker With Colored Nine,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), July 15, 1942: 10.

4 “Cincinnati Clowns to Open Season,” Macon Telegraph, March 29, 1943: 2.

5 “Clowns to Meet Monarchs Tonight,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), September 14, 1943: 11.

6 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/John_Britton.

7 See the Dallas Morning News, July 28, 1943: Section Two, 7, and the New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 27, 1943: 12.

8 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House, 2001), 406.

9 Holway, 413.

10 “Grays, Barons Meet Tuesday,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 17, 1944: 24.

11 Ibid. See also John Klima, Willie’s Boys (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), 40.

12 “Black Barons Back at Top Strength,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 31, 1945: 9.

13 John Virtue, South of the Color Barrier: How Jorge Pasquel and the Mexican League Pushed Baseball Toward Racial Integration (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 78.

14 Mexican League statistics are courtesy of SABR member Dr. Virgilio Partida, citing Pedro Treto-Cisneros, editor. Enciclopedia del Biesbol Mexicano, eighth edition (Mexico City, 2015).

15 The source for this is the unattributed player record in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

16 Joel W. Smith, “Jackie Robinson All-Stars Beat Creoles Before 7,500,” Atlanta Daily World, October 18, 1949: 5.

17 Chicago Defender, May 27, 1950: 19.

18 His first appearing with Elmwood is noted by Bob Moir, “Wells’ Double Beats Carman in Tenth,” Winnipeg Free Press, May 25, 1950: 16.

19 “Contract-jumpers in Loop?” Brandon (Manitoba) Daily Sun, June 23, 1950: 2.

20 Jim Reid, “Dropped Third Strike Gives Greys Win,” Brandon Daily Sun, May 29, 1950: 2.

21 Barry Swanton, The Mandak League: Haven for Former Negro League Ballplayers, 1950-1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2006), 79.

22 Associated Press, “Veeck Sets Precedence by Farming Pair to Jap Loop,” Morning Advocate (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), April 29, 1952: 11. Rob Fitts comments: “The first African-American player to play professionally in Japan was actually Jimmy Bonna, who played in 7 games for the 1936 Dai Tokyo team. Although he hit .458 he did not stay with the team and had little impact on the history of Japanese baseball.” Fitts’ February 25, 2013, post is found at agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2013/02/early-black-ballplayers-in-japan.html.

23 Jet, May 15, 1952: 51.

24 Harold W. Robbins, “Satchel Paige Does Not Appear at Pynchon Park,” Springfield Republican, June 27, 1954: 7.

25 Associated Press, “Negro League Greats Gather to Reminisce About Old Times,” Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, June 5, 1989: B5.

Full Name

John A. Britton

Born

April 21, 1919 at Mount Vernon, GA (US)

Died

December 2, 1990 at Oak Forest, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.