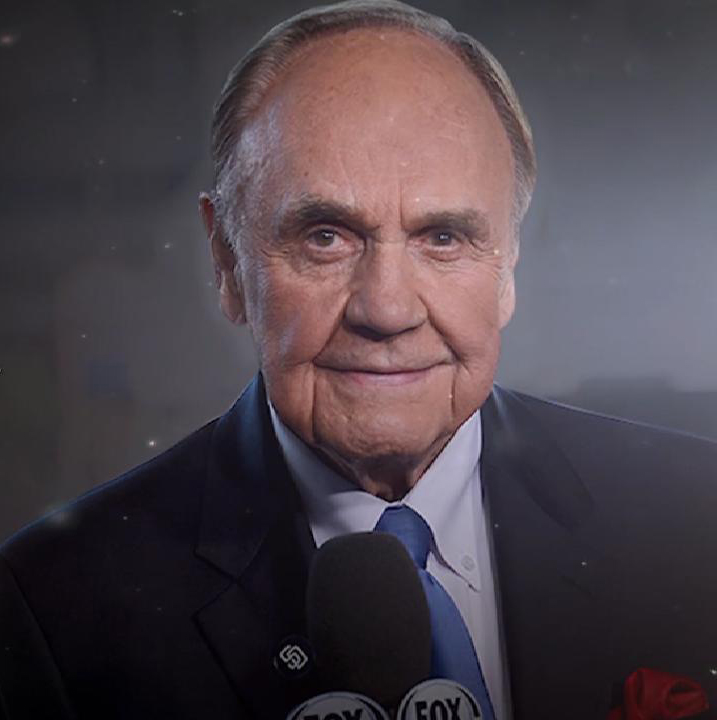

Dick Enberg

Few post-1960 sportscasters have enjoyed a broader national impact in the United States than Dick Enberg. During his 60-year career, Enberg was a fixture for NBC and CBS television networks, delivering his signature exclamation “Oh My!” while announcing NFL football (including eight Super Bowls), college basketball (including four Final Fours), Wimbledon tennis, and events in numerous other sports. New York Times writer Billy Witz suggested that Enberg’s voice was “one that would lend an air of legitimacy and excitement to cockroach races.”1 Upon Enberg’s passing in 2017, no less an authority than Vin Scully released a statement via the Dodgers’ Twitter feed that read in part, “To me, Dick Enberg was the greatest all-around sportscaster who ever lived and will never be emulated.”2

Few post-1960 sportscasters have enjoyed a broader national impact in the United States than Dick Enberg. During his 60-year career, Enberg was a fixture for NBC and CBS television networks, delivering his signature exclamation “Oh My!” while announcing NFL football (including eight Super Bowls), college basketball (including four Final Fours), Wimbledon tennis, and events in numerous other sports. New York Times writer Billy Witz suggested that Enberg’s voice was “one that would lend an air of legitimacy and excitement to cockroach races.”1 Upon Enberg’s passing in 2017, no less an authority than Vin Scully released a statement via the Dodgers’ Twitter feed that read in part, “To me, Dick Enberg was the greatest all-around sportscaster who ever lived and will never be emulated.”2

Yet what readers from outside southern California, especially younger ones, may not know is that Enberg was a daily baseball play-by-play announcer both toward the beginning of his career, with the Angels on radio, and toward the end of it, with the Padres on television. In fact, in 2015, one year before his retirement from the San Diego booth, he received the Ford C. Frick Award from the Baseball Hall of Fame for his broadcasting contributions to the sport.3

Yet, for all of his many awards and his relaxed, upbeat delivery on the air, Enberg was not without his own personal doubts and insecurities. Enberg was open about the latter in some of his broadcasts and writings. One cannot know for sure, but arguably his candor and tendency to wear his heart on his sleeve, brought Enberg closer to his listeners.

Growing Up

Enberg’s youth was split between Michigan — where he was born on January 9, 1935, departed with his family in 1937, returned in 1946, and graduated high school in 1952 — and southern California, where he spent most of his childhood (1940-1946).4 The Enberg family, including Dick’s parents Arnie and Belle, also spent a brief stint in Connecticut (1937-1940) when Dick was a toddler. Enberg’s childhood and adolescence were largely spent in rural settings: The San Fernando Valley (north of Los Angeles) was much more rural then than it is now, and in Michigan, he lived on a farm run by his father in the village of Armada, Michigan and graduated from high school in a class of 33.5

Higher Education

Enberg continued on to college at nearby Central Michigan University in Mount Pleasant, aided by a $100 scholarship. He majored in physical education (what today at most universities is called kinesiology or exercise-sports science), but soon found himself behind microphones. He served first as the public-address announcer of CMU football and basketball during 1955-56, and then as an on-air personality at radio station WCEN, where he began as a dollar-an-hour disc jockey and later announced sports.6 He graduated from CMU in 1957.

Excited by teaching and learning, as well as sports, Enberg chose to attend graduate school to study health and physical education. Indiana University in Bloomington offered him a much bigger scholarship ($1,000)7 than he had received for his undergraduate studies at Central Michigan, so he quickly decided to become a Hoosier. While at Indiana, he took a sports broadcasting class from a professor who made it a point to find announcing gigs for his students while they were still in school. This development gave Enberg the opportunity to do play-by-play of IU basketball and football. Also while at Indiana, Enberg fell in love with broadcast student Jeri Suer, whom he married in 1959.

Enberg began to become a known quantity in the region, attracting an invitation in 1961 to do basketball telecasts of defending national champion Ohio State’s late-round NCAA tourney games back to Columbus. Then, when the University of Cincinnati made the title game against the Buckeyes, the championship broadcast was added to the Cincy television market as well.8

Upon completion of his doctorate in 1961, with a 400-page dissertation on athletic injury prevention to show for it9, Enberg was hoping to remain at IU as a faculty member. No offer came his way, however, so he had to choose among other institutions. As if attracted by magnetic force, Enberg ended up back in southern California, landing a two-part job at San Fernando Valley State College (later California State University Northridge) as assistant professor and assistant coach of the baseball team. Enberg initially sought out some broadcasting opportunities, as well, to supplement his income.10 He spent four years at Valley State, before broadcasting pulled him away from academia once and for all.11

The stint as assistant baseball coach, in fact, led to what would become Enberg’s famed home-run call. According to a Sports Video Group article, “To encourage his players for a base hit, Enberg and the coaching staff would yell out, ‘Touch ’em all!…’”12

Early Announcing in Los Angeles

While at Valley State, Enberg did radio work, first at KGIL, then at KLAC and KNX. His duties included a nighttime scoreboard show on Fridays and Saturdays during football season.13 He even announced a water polo match for local television, overcoming his lack of previous exposure to the sport with the kind of preparation — reading two books on water polo and attending five matches14 — that would be a hallmark of his career.

Shortly thereafter, in 1965 and ’66, Enberg emerged on the Los Angeles broadcasting scene, getting jobs doing the nightly sports on the KTLA Channel 5 news, hosting the then-California Angels’ pre- and postgame radio shows, and calling play-by-play for Rams radio broadcasts and UCLA basketball telecasts. As Enberg noted in a 1993 Los Angeles Times interview, “I got all four of those jobs within an 18-month span.”15 Later, in 2016, he expounded on his non-stop work docket, one that he says cost him his first marriage: “You didn’t want to say ‘no’ in our business … ’cause there’s so many people lined up that want to say ‘yes’.”16

Enberg initially got into the Rams’ radio booth in 1966 as lead announcer Bob Kelley’s No. 2 person, a role that according to Enberg entailed “reading commercials, giving scores, and doing halftime interviews.”17 Like Enberg, Kelley was also a legendary broadcasting wunderkind, beginning his announcing career in 1937 at age 20 with the then-Cleveland Rams. Kelley had been broadcasting Rams game for nearly 30 years, before his untimely death of a heart attack in 1966; he was not even 50 years old when he passed away.18

Enberg immediately took over for Kelley in ’66, bonding strongly with both the Rams franchise — taking the team’s many playoff near-misses hard — and some of its players. One in particular was defensive tackle Merlin Olsen. Enberg noted that, even after a Rams loss, when many players would not be eager to provide a postgame interview, Olsen could be counted on to offer thoughtful reflections on the game.19 Enberg and Olsen would, of course, be reunited as an NBC broadcast team down the road (discussed below).

Played only once a week, football creates a unique sense of anticipation and game-day experience among fans and others associated with the sport. Enberg reveled in this atmosphere, arriving hours before the game, grabbing a hot dog in the press box, going down to the field and locker rooms to chat up coaches and other announcers, and, when at the L.A. Coliseum for a Rams home game, marveling at the view of the field coming out of the locker-room tunnels.20

And then there was UCLA basketball, a regular national-championship machine under the great coach John Wooden. Naturally, Enberg meshed well with the philosophical, Renaissance man Wooden. Wrote Enberg of the UCLA coach, “His interests are so much wider than just basketball. Besides his love for poetry … I think he could quote from every book ever written on Abraham Lincoln. As his players will tell you, he was a brilliant teacher and certainly an inspiration. I found him to be the ultimate example of not only greatness, but also goodness.”21

In the late 1960s and early ‘70s, KTLA would record home UCLA basketball games with Enberg doing play-by-play, for tape-delayed broadcast at 11:00 pm. This delayed telecast format figures prominently in a humorous anecdote from Enberg’s career, discussed below.

Local Baseball Broadcasting

Angels

As noted, Enberg’s radio work with the Angels began with hosting pre- and post-game shows from 1966-1968, before he took over play-by-play duties in 1969. He continued in this role until 1978, teaming with Don Wells in 1969, with Wells and Dave Niehaus22 from 1970-1972, and with Don Drysdale from 1973-78.23 Enberg also returned to call 40 Halos’ games in 1985.24

Enberg’s first Angels play-by-play radio broadcast, from April 8, 1969, is preserved on YouTube.25 While interviewing Angels manager Bill Rigney for the pregame show, Enberg asks the skipper if he has “Any advice to a rookie announcer who’s breaking into the big leagues tonight to try to cool the butterflies a bit?” Enberg’s expressed nervousness may be surprising, as by this time he was already a seasoned announcer of major sporting events (Rams games and, as discussed below, college basketball). And despite the “butterflies,” Enberg appears as polished as ever in his Angels debut.

In the top of the first of the Angels’ 1969 opener, the Seattle Pilots’ Mike Hegan drove a blast to right-center, to which Enberg exclaimed, “Hegan will touch ‘em all!” This even-handedness, exemplified by how Enberg narrated an opposing home run as energetically as he would an Angels homer, was long a part of his approach (see, however, the Padres section below).

Enberg was open about tensions between him and Wells, stemming from how the less-experienced Enberg was hired for the Angels’ lead play-by-play role over Wells, despite the latter having been an Angels announcer since the franchise’s 1961 debut. The rift with Wells and Enberg’s own insecurity led him nearly to quit the Angels gig, but Enberg remained and reported learning some valuable broadcasting lessons from Wells.26

The Angels did not win often during Enberg’s years in the booth. As he lamented in a 2002 Los Angeles Times interview, “The Angels seemed to have a knack for finding last place and staying there.”27 On a positive note, however, Angel pitchers provided Enberg with an ample supply of his favorite baseball experience to announce, the no-hitter. While interviewing Vin Scully in 2016 to mark the Dodger great’s final year behind the microphone,28 Enberg noted that he, himself, had done “only” nine no-hitters over his career, compared to Scully’s 23. Of the no-hitters called by Enberg that were pitched by Angel arms, four were courtesy of Nolan Ryan (two in 1973 and one each in 1974 and 1975) and one was delivered by Clyde Wright in 1970.29

Angel pitchers’ no-hitters may have sustained Enberg’s enjoyment of announcing for the team a bit, but Enberg primarily credits his longevity with the Halos to broadcast partner Drysdale: “The dog days in baseball are real, particularly in August with a bad team. But there was never a dog day working with Don … We worked together for six years, and we laughed for six years.”30

Padres

Enberg’s return to local baseball play-by-play, on television rather than radio, after three decades of national football and basketball broadcasting (among other sports) began with an August 2009 breakfast date with Padres president Tom Garfinkel. As Enberg told the New York Times, “I said, ʻI think this guy’s offering me a job.’”31

Enberg received the Padres’ offer, all right, and took it, one provision being that he could still announce Wimbledon and other tennis tournaments during baseball season. One thing that, at some point in 2010, changed in Enberg’s style was the injection of some limited partisanship into his calls. As the New York Times reported, “in this proudly provincial [San Diego] market, and after a talk with Garfinkel, Enberg agreed to drop his home run call — ‘He’ll touch ’em all’ — for the opposing team.”32 In a 2014 interview, Enberg claimed that national broadcasting for so many years had reinforced his penchant for neutrality.33

Enberg ended up calling Padres games for seven years, until the end of the 2016 season, when he was 81. On the day of Enberg’s final home game, Padres’ groundskeepers mowed the grass in center-field to make the phrase “OH MY!” stand out.34

National Broadcasting

TVS

Enberg’s role announcing UCLA basketball telecasts put him in position to do the play-by-play for the January 20, 1968 UCLA at Houston “Game of the Century” from the Astrodome, featuring the Bruins’ Lew Alcindor (later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and the Cougars’ Elvin Hayes. This contest was the first nationally-televised, regular-season college basketball game ever.35 The UCLA-Houston broadcast had been organized by Eddie Einhorn (later part-owner of the Chicago White Sox), like Enberg in his early 30s at the time, for Einhorn’s fledgling TVS syndicated sports broadcasting network. TVS would continue broadcasting college basketball into the 1970s, primarily in the Midwest, with Enberg behind the mic.

NBC

Enberg’s jump from being a southern California-based broadcaster — with the Angels, Rams, and UCLA basketball — to a national announcer with NBC occurred in stages, rather than all at once. The transition began in the fall of 1975, driven in part by NBC’s creation of a men’s college basketball Game of the Week, called by Enberg. His final Rams game was a first-round playoff loss to the Minnesota Vikings on the day after Christmas in 1977, whereas his final season in the Angels’ broadcast booth was 1978.

Enberg’s work at NBC included baseball. However, as discussed below, his time at the peacock-logo network was better known for his broadcasts of other sports. During Enberg’s initial years at NBC, Joe Garagiola and Tony Kubek comprised the lead announcing team for the network’s Saturday Game of the Week baseball broadcasts.36 Enberg did some Saturday games as part of a secondary broadcast team, but got to work on a three-person team with Garagiola and Kubek in calling the 1982 World Series.37 Enberg’s baseball broadcast partners at NBC also included Tom Seaver,38 an active player at the time who moved into the booth for the 1981 playoffs.

In the summer of 1983, Enberg traveled to Helsinki, Finland, the land of his family heritage, to cover the inaugural World Track and Field Championships. He was fully expecting to announce the 1983 World Series as well, so he took copies of the Sporting News and other baseball publications to Finland, to study up during track and field downtime. During this time, however, he learned that NBC had hired Vin Scully for lead baseball duties, 39 bringing Enberg’s national baseball announcing career to an end.

Though Enberg announced college basketball for NBC as far back as the fall of 1975, Curt Gowdy called the 1976 and 1977 men’s title matchups. Hence, Enberg’s first call of a national championship game for the network occurred in 1978, featuring Kentucky vs. Duke. That game featured the legendary announcing trio of Enberg, Billy Packer, and Al McGuire, the latter having retired from coaching the year before after leading Marquette to the national championship. Many years later, Enberg expressed his longtime devotion to McGuire (who died in 2001) by writing a one-man play entitled “Coach,” drawing upon McGuire’s philosophies and witticisms. The play debuted in 2005.40

Enberg’s second NCAA basketball title game was one of the sport’s classics, the 1979 Michigan State-Indiana State contest featuring Magic Johnson for the Spartans and Larry Bird for the Sycamores. CBS took over the men’s NCAA basketball tourney in 1982, ending Enberg’s string of announcing national title games.

Just as he had done with McGuire and Packer in college basketball, Enberg formed a celebrated broadcast partnership with former Los Angeles Ram Merlin Olsen in football (1978-1988). As noted above, Enberg and Olsen had a special bond dating back to the latter’s playing days with the Rams. Further, as thoroughly as Enberg prepared for games, he met his match in Olsen, who would show up at games with lengthy lists of facts and ideas written out on yellow legal pads for himself, Enberg, the director, and producer.41

Enberg also announced Wimbledon tennis for NBC, beginning in 1979, coinciding with the introduction of live broadcasts of the finals back to the US42 (the time difference between the UK and US meant 6:00 or 7:00 am starts for viewers in some US time zones, so NBC previously had shown final matches only on tape-delay). These morning broadcasts, teaming Enberg with Bud Collins, became known as “Breakfast at Wimbledon.” Enberg’s final Wimbledon was in 2011. In addition, Enberg announced French Open tennis for NBC.

CBS

NBC’s loss of broadcast rights to the NFL in 1998, on top of the network’s diminished role in NCAA basketball coverage, led Enberg to move to CBS in 2000.43 Among other things, the move allowed Enberg to reunite briefly with Packer and McGuire in broadcasting college basketball.44 At CBS, Enberg partnered with former football player Dan Dierdorf to call NFL games and also announced US Open tennis.

ESPN

Enberg announced tennis at ESPN, as the all-sports cable network began to take over more of the sport’s coverage from NBC. He broadcast Wimbledon tournaments for ESPN from 2004-2011,45 as well as the Australian Open from 2005-2011.46 47 Reflected former Wimbledon champion Stan Smith, “I was able to be involved at NBC with Dick for five years here at Wimbledon and he always loved being over here, he loved following the tennis, he knew the tennis well, [and] he knew the players well …”48

Honors

Enberg won numerous broadcasting honors, including the aforementioned Ford Frick Award from the Baseball Hall of Fame. He was also honored by the Basketball49, Football50, and Sports Broadcasting51 Halls of Fame. Enberg also won a total of 13 Sports Emmy Awards for his television work.52

Sports Essayist

All through his broadcasting career, but perhaps most heavily in the latter years, Enberg wrote and delivered a number of sports essays, sometimes accompanied by music, during television broadcasts. At the 2016 Point Loma (California) Writer’s Symposium by the Sea, he expounded on his view that announcing a game has certain parallels with being a writer of novels, such as the featuring of characters and the story arc of beginning, middle, and end.53 At the same forum, Enberg went to the core of his broadcast essays: “I write with my heart … I get emotional, so maybe I can write well enough that the audience will feel the same way …” An example of Enberg’s essay work, a tribute to the Open Era of U.S. Open tennis (starting in 1968, in which professionals could compete), is available on YouTube.54

Marriages and Children

Enberg had three children with his first wife, Jeri, before divorce ended their marriage in 1973.55 Enberg wrote openly and extensively about his divorce in Oh My! A dramatic incident he recounted, capturing how his unrelenting work activities appeared increasingly to alienate Jeri, involved a trip the two took to the 1972 Munich Summer Olympics. Whereas Jeri expected to spend time with her husband on this trip, Enberg spent a great deal of time working on the broadcast essays he was assigned to do. Jeri responded by leaving early to travel alone back to the States. They were divorced a year later.

By coincidence, Stan Charnofsky, the head baseball coach at Valley State when Enberg was the assistant, like Enberg held a doctoral degree, with Charnorsky’s being in counseling psychology. Enberg “poured out my anguish“ to Charnofsky.56 Enberg also began co-writing a book with Charnofsky about divorce,57 but ultimately Enberg’s contribution was the foreword to a 1992 Charnofsky book.58

While working for NBC, Enberg met and then married (1983) his second wife, Barbara Hedbring (née Almori), and they remained together until Dick’s death. They also had three children of their own: Ted, who became a sportscaster;59 Nicole, who graduated from the University of Michigan, renewing the family’s ties to the state, and later worked in public relations for the news divisions at CBS, ABC, and NBC;60 and Emily, a world traveler, filmmaker, and environmentalist.61

Humorous Anecdotes

Two incidents discussed in Oh My! illustrate Enberg’s ability to improvise himself out of potentially embarrassing situations.

One occurred during a time in Enberg’s career in which he was working almost literally non-stop, pulling triple-duty during college-basketball weekends. He would announce a UCLA home game on Friday night, rush to LAX for a red-eye flight to the Midwest to do a live broadcast of a Saturday afternoon game on Einhorn’s TVS (involving teams such as Notre Dame), and then fly back to Los Angeles in time to do UCLA’s Saturday night game. To pull this off, Enberg would drive from some Midwestern airport directly to the arena on Saturday morning, ask to use one of the locker rooms to shower and shave, and be ready to call the game by afternoon. As was almost certain to happen at some point, however, inclement weather delayed one of his return flights, messing up his carefully-laid plans. On one of the Saturday nights, he couldn’t get to UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion in time for the game, but could get to the KTLA studio by the game’s 11:00 pm airtime, where he did voiceover on a videotape of the game!

The second incident, also in college basketball, occurred during a TVS first-round NCAA tournament broadcast, for which Enberg was assigned a partner with whom he had never before worked. As the cameras went live, Enberg began his usual welcoming remarks to the television audience, only to realize he was drawing a blank on the other announcer’s name! Enberg did the best he could under the circumstances, turning to his colleague and inviting him to “come on in and introduce yourself.”

Game Shows and Movies

In addition to play-by-play broadcasting, Enberg also hosted the game show Sports Challenge from 1971-1979. Sports Challenge was a half-hour, quiz-show competition, pitting three-member teams representing different franchises against one another. One 1971 show, for example, featured a 1950s- and ’60s-era Boston Celtics trio of executive Red Auerbach, retired player-coach Bill Russell, and active player John Havlicek vs. a contemporary (at the time) Washington Senators outfit of manager Ted Williams and players Frank Howard and Denny McLain.62 The show revolved around video clips of classic sports moments, with the quiz questions being related to the clips. Enberg did play-by-play voiceovers on these clips when the audio accompaniment from the original announcers was not available.63

Enberg also hosted three non-sports game shows, The Perfect Match (1967), Baffle (1973), and Three for the Money (1975),64 all for a year or less.65 He even extended the reach of his media persona, taking on sportscaster roles in many movies.66

Final Years

Enberg’s final media appearance was on a 50-year retrospective on the 1968 basketball “Game of the Century” between UCLA and Houston. The show, for cable television’s CBS Sports Network, was filmed on November 3, 2017, and debuted on January 15, 2018.67 Jim Nantz, who moderated the show, later offered this reflection:68

“To think about the symmetry of this: [Enberg’s] first and ‘most meaningful’ broadcast was UCLA-Houston [in 1968], where the nation was eyewitness finally to his magical prose. And now, he’s looking back on it 50 years later, and then he’s gone … How does that work?”

On Thursday, December 21, 2017, Enberg was scheduled to fly from San Diego to Boston to meet his wife Barbara and other family members. However, he never made it out of his house. Barbara told the San Diego Union-Tribune that, “He was dressed with his bags packed at the door … We think it was a heart attack.”69

After Enberg died, the Union-Tribune reproduced a collection of Twitter tweets honoring him.70 The authors of these tweets represented a diverse group, including NBC news anchor Tom Brokaw, Syracuse basketball coach Jim Boeheim, tennis great Chris Evert, former New York Giants quarterback (and one-time Enberg broadcast partner) Phil Simms, and the singer Cher.

Enberg had at least two endeavors planned for his retirement from formal broadcasting duties. One was a podcast called “The Sound of Success,” the first episode of which aired on October 4, 2017, just months before Enberg’s death.71 The other was a book, entitled Being Ted Williams, on the Red Sox great, published posthumously.72

In one interview late in his career, Enberg tried to dispel the notion that a sportscaster needed to know everything about every sport. “That’s what the color commentator is there for,” he said. “You throw in an ‘Oh My!’ and there you go …”73

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 New York Times, August 7, 2010. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/08/sports/baseball/08enberg.html

2 Los Angeles Dodgers, Twitter tweet, December 22, 2017.

3 National Baseball Hall of Fame, 2015. Retrieved from: https://baseballhall.org/discover/awards/ford-c-frick/dick-enberg-2015-ford-c-frick-award-winner

4 Dick Enberg (with Jim Perry), Oh My! (New York: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004). Enberg had two siblings, with his brother Dennis born in 1939 and his sister Sharyl born in 1945.

5 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

6 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

7 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

8 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

9 Many online articles about Enberg refer to his holding a doctorate (without the specific degree noted) in “health sciences.” According to the 1961-1962 Academic Bulletin of Indiana University’s School of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, the unit awarded a few different types of doctoral degrees. Based on Enberg’s dissertation topic, he most likely received a Doctor of Health and Safety (HSD) or Doctor of Physical Education (PED). Retrieved from: http://institutionalmemory.iu.edu/aim/bitstream/handle/10333/4525/1961-62_HPER_Bulletin.pdf

10 Curt Smith, Voices of Summer (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005).

11 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

12 Sports Video Group, December 22, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.sportsvideo.org/2017/12/22/sports-broadcasting-hall-of-famer-dick-enberg-dies-at-82/

13 Los Angeles Times, January 25, 1993. Retrieved from: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-01-25-sp-1704-story.html

14 Sports Illustrated, August 21, 1978. Retrieved from: https://www.si.com/vault/1978/08/21/822901/training-to-run-an-anchor-leg

15 Sports Illustrated, 1978.

16 Point Loma Writer’s Symposium by the Sea. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CBmeysXKbqw

17 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004, p. 60.

18 Kelley began announcing for the then-Cleveland Rams in 1937 at age 20, moved with the team to Los Angeles in 1946, and remained with the Rams until his death in 1966. Orange County Register, August 19, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.ocregister.com/2016/08/19/50-years-later-rams-will-have-a-kelley-back-in-the-710-radio-booth/

19 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

20 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

21 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004, p. 84.

22 Like Enberg, Niehaus was an Indiana University graduate. Fansided, November 10, 2015. Retrieved from: https://sodomojo.com/2015/11/10/remembering-the-voice-of-the-mariners-dave-niehaus/

23 Los Angeles Times, October 11, 2002. Retrieved from: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-oct-11-sp-tvcol11-story.html

24 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

25 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N29Qd0ZKqRM

26 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

27 Los Angeles Times, October 11, 2002. Retrieved from: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-oct-11-sp-tvcol11-story.html

28 YouTube video of Enberg interviewing Vin Scully: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2PxAfCY6ue8.

29 The other four no-hitters all came against teams Enberg was announcing for: a shared no-hitter by three Oakland pitchers against the Angels in 1975; no-hitters by Cleveland’s Dennis Eckersley and Texas’s Bert Blyleven against the Halos in 1977; and one by the Giants’ Tim Lincecum against the Padres in 2014. See ESPN’s list of no-hitters at: http://www.espn.com/mlb/history/nohitters

30 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004, p. 102.

31 New York Times, August 7, 2010.

32 New York Times, August 7, 2010.

33 ASAP Sports, transcript of Enberg interview at 2014 MLB Winter Meetings. Retrieved from: http://www.asapsports.com/show_interview.php?id=105180

34 Patrick Whittle, Twitter tweet, September 29, 2016.

35 A DVD of the second half of the classic UCLA-Houston basketball contest, with Enberg’s play-by-play, comes with the book How March Became Madness: How the NCAA Tournament Became the Greatest Sporting Event in America by Eddie Einhorn and Ron Rapoport, published in 2006 by Triumph Books.

36 Associated Press, March 23, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.syracuse.com/sports/2016/03/former_baseball_broadcaster_today_host_joe_garagiola_dies_at_age_90.html

37 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VS0mI8AkVXc

38 Danny Gallagher’s book Blue Monday: The Expos, the Dodgers, and the Home Run That Changed Everything (2018, Dundurn Press) alludes to Enberg and Seaver’s call of the top of the ninth inning, in which Rick Monday’s go-ahead home run propelled Los Angeles to victory in the deciding game of the 1981 National League Championship Series.

39 NBC Sports “Our History,” Dick Enberg on Vin Scully Hiring. Retrieved from: https://www.nbcsports.com/video/dick-enberg-vin-scully-hiring

40 Video excerpts of the play can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hua-TrUeLb8

41 Television Academy interview with Dick Enberg, August 17, 2011. Retrieved from: https://interviews.televisionacademy.com/interviews/dick-enberg

42 ESPN Press Room, June 30, 2011. Retrieved from: https://espnpressroom.com/us/press-releases/2011/06/wimbledon-enbergs-finale-marked-by-enbergs-reflections-vignettes/

43 UPI Archives, January 19, 2000. https://www.upi.com/Archives/2000/01/19/Dick-Enberg-moves-to-CBS/2091948258000/

44 The Oklahoman, January 20, 2000. Retrieved from: https://oklahoman.com/article/2683291/enberg-reunited-with-pals

45 ESPN Press Room, 2011.

46 San Diego Union-Tribune, May 21, 2004. Retrieved from: https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-enberg-is-grand-and-now-he-gets-to-call-the-slam-2004may21-story.html

47 American Sportscasters Online [appears from context of Enberg’s final Wimbledon to be from 2011]. Retrieved from: http://www.americansportscastersonline.com/enberglastwimbledon.html

48 ESPN Press Room, 2011.

49 Enberg received the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame’s Curt Gowdy Award in 1995: http://www.hoophall.com/awards/curt-gowdy-media-awards/

50 Enberg received the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s Pete Rozelle Award in 1999: https://www.the-daily-record.com/x870254956/Pete-Rozelle-Radio-TV-Award-recipients

51 https://www.sportsbroadcastinghalloffame.org/inductees/dick-enberg/

52 Enberg’s undergraduate alma mater, Central Michigan University, enumerates his Emmy Awards as follows: “as a sportscaster (1981, 1983, 1990, 1993), writer (1988, 1994, 1997, 1998, 1999 [2], 2004) and producer (1978)… [and] a Lifetime Achievement Emmy Award in 2000.” Retrieved from: https://www.cmich.edu/alumni/Connect/NotableAlumni/Pages/AlumniBio.aspx?itemID=9. As noted in Oh My!, the Emmy for production came for an episode (on Roger Maris, co-produced by Enberg) of the public broadcasting series The Way it Was.

53 Point Loma Writer’s Symposium by the Sea.

54 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWuYmUq5S38

55 Marriage and divorce information retrieved from: https://marriedbiography.com/dick-enberg-biography/

56 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004, p. 120.

57 Sports Illustrated, August 21, 1978.

58 Stan Charnofsky, When Women Leave Men: How Men Feel, How Men Heal (Novato, California, New World Library, 1992).

59 American Sportscasters Online, circa 2016, retrieved from: http://www.americansportscastersonline.com/ted_enberg_article.html

60 https://www.linkedin.com/in/nicole-enberg-vaz-2ab8b84

61 https://www.gwalumni.org/2019/03/fighting-plastic-waste-one-tile-at-a-time/

62 Many Sports Challenge episodes are available on YouTube. The Celtics-Senators match is at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YYABbCM9nfo

63 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

64 Video clips of selected episodes of these shows are available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZTVkJpqFTfU, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aBNFxZkq1XE, and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2A2oJ95e6ig.

65 Enberg, Oh My!, 2004.

66 https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0256718/?ref_=tt_cl_t1

67 I maintain an historical blog on the Game of the Century and I wrote about the 50-year retrospective show at: http://gameofthecentury.blogspot.com/2018/01/cbs-sports-network-special-on-gotc-50th.html

68 Orange County Register, January 13, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.ocregister.com/2018/01/13/hoffarth-enbergs-voice-resonates-50-years-after-the-ucla-houston-game-of-the-century/

69 San Diego Union-Tribune, December 21, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/sd-sp-dick-enberg-death-obit-20171221-story.html

70 San Diego Union-Tribune, December 22, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sports/sd-sp-dick-enberg-death-memories-sports-20171222-story.html

71 Radio Insight, October 4, 2017. Retrieved from: https://radioinsight.com/headlines/120092/dick-enberg-joins-podcast-one-sound-success/. A brief excerpt of Enberg’s debut podcast interview with Billie Jean King is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fFWsgYaityQ

72 Dick Enberg (with Tom Clavin), Being Ted Williams: Growing Up with a Baseball Idol (New York: Sports Publishing, 2018).https://www.skyhorsepublishing.com/sports-publishing/9781683582212/being-ted-williams/

73 Author’s recollection.

Full Name

Richard Alan Enberg

Born

January 9, 1937 at Mount Clemens, MI (US)

Died

December 21, 2017 at La Jolla, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.