A Ballpark as a Political Football: Florida, Illinois, and a New Home for the White Sox

This article appears in SABR’s “The Base Ball Palace of the World: Comiskey Park” (2019), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

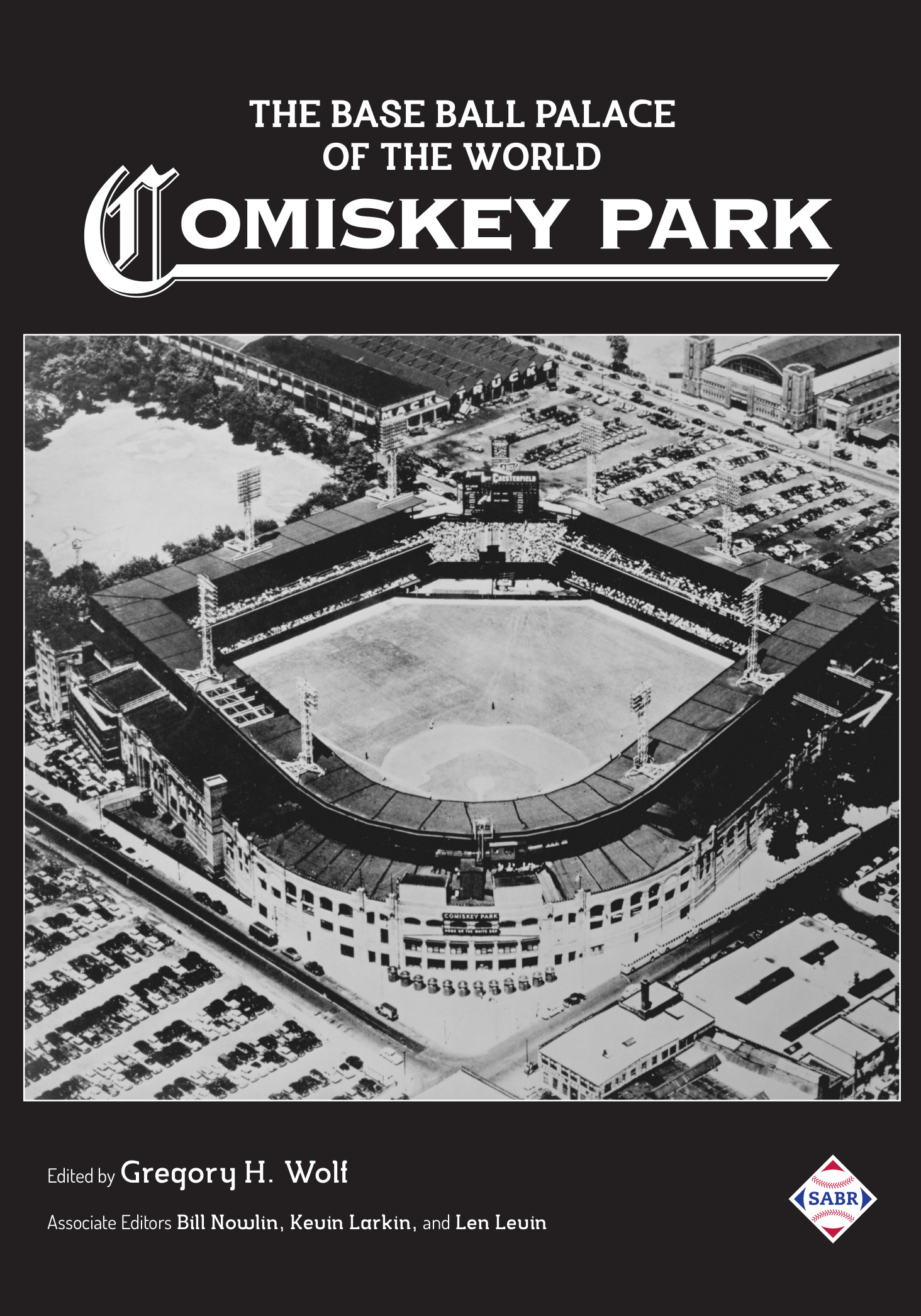

Comiskey Park opened during the summer of 1910,1 and the Chicago White Sox broke in their new home with a 2-0 loss to the St. Louis Browns. After hosting decades of American League baseball on the South Side of Chicago, as well as three World Series, Comiskey Park indeed showed its age during the summer of 1988. As with many major-league baseball teams during that era, the White Sox advocated for a new ballpark. With a scarcity of major-league teams and several booming cities seeking teams of their own, the threat of relocation would provide ample leverage for public financing of new ballparks to ensure that existing teams stayed put. For the White Sox, that formula would be applied to the effort to replace Comiskey Park with a new palace suitable for the modern era of baseball.

Comiskey Park opened during the summer of 1910,1 and the Chicago White Sox broke in their new home with a 2-0 loss to the St. Louis Browns. After hosting decades of American League baseball on the South Side of Chicago, as well as three World Series, Comiskey Park indeed showed its age during the summer of 1988. As with many major-league baseball teams during that era, the White Sox advocated for a new ballpark. With a scarcity of major-league teams and several booming cities seeking teams of their own, the threat of relocation would provide ample leverage for public financing of new ballparks to ensure that existing teams stayed put. For the White Sox, that formula would be applied to the effort to replace Comiskey Park with a new palace suitable for the modern era of baseball.

Indeed, the formula had already been applied with an apparently successful result. The White Sox seemed to have been saved through a 1986 legislative package that established an authority to oversee construction of a new ballpark and authorized the sale of bonds and new hotel taxes to finance the deal. By the spring of 1988, however, Comiskey Park continued to crumble with virtually no progress having been made on its presumed replacement. St. Petersburg, Florida, sensed an opportunity and pounced. Unlike Chicago, there was a new ballpark on the rise in St. Petersburg as the 43,000-seat Suncoast Dome inched toward readiness for major-league baseball. Though the fourth largest state in population in 1988, Florida lacked major-league baseball. The Suncoast Dome served as the bait. Of existing teams seeking new homes, the White Sox appeared to be the most desperate. A native Chicagoan, Commissioner Peter Ueberroth, acknowledged the situation. He said, “The White Sox are No. 1 on my watch list. … [I]f they can’t get the stadium they need in Chicago by the time they need it, I would not stand in their way.”2

The combination of a courtship from Florida and inaction in Illinois presented White Sox managing partners Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn with an opportunity to play off two states in search of the best deal. St. Petersburg was going all-in to secure the White Sox. One member of the local Chamber of Commerce sold dozens of “Florida White Sox” T-shirts with more on the way, and a local radio station commissioned and regularly played the song “Come on White Sox.”3 Governor Bob Martinez overcame initial reluctance and confirmed his support for a $30 million legislative package intended to ready the Suncoast Dome for Opening Day 1989. “Let’s play ball,” he said.4 In Illinois, almost two years of inaction provided the White Sox with an opening to get a better deal. In particular, the club hoped to renegotiate the part of the 1986 deal that required annual rent payments of $4 million and establish firm deadlines for the construction of a new stadium. By early May 1988, there was no guarantee that a better deal would be good enough for the White Sox. The club paid $25,000 for a feasibility study on the use of venerable Al Lang Stadium as a temporary home until the dome was completed.5 Reinsdorf and Einhorn said the right things about staying, but it was suggested that their business partners were ready to accept the financial benefits offered by moving.6

Illinois Governor James “Big Jim” Thompson, whose arm-twisting helped secure passage of the 1986 deal, jumped back into fray. He declared, “I will do everything in my power to keep the Sox in Chicago.”7 Thompson authorized Deputy Governor James Reilly to assemble the principals to hammer out a deal. Starting on May 2, 1988, Reilly hosted a series of meetings with Reinsdorf and Einhorn in addition to Al Johnson, a representative of Chicago Mayor Eugene Sawyer, and Thomas Reynolds Jr., chairman of the Illinois Sports Facilities Authority (ISFA). The authority had been created by the 1986 legislation to issue $120 million in bonds and oversee construction of a new ballpark. Reinsdorf and Einhorn remained coy about their specific demands, but Reynolds noted that White Sox rent payments might be reduced because hotel tax revenues were exceeding projections.8 The group hoped to craft a deal that would not require legislative approval, but it became apparent that the Illinois General Assembly might have to vote on a revised package.

The parties reached a tentative deal on May 9, but the apparent solution unraveled shortly before a planned press conference. Reilly said the governor’s office and ISFA agreed to the White Sox’ financial demands to the savings of approximately $60 million, but Reinsdorf and Einhorn would not consent to a request to suspend negotiations with St. Petersburg until the Illinois legislature could act on the package. Reilly complained, “We never told them to kill St. Petersburg’s deal. We just said stop talking until our legislature ends. They couldn’t do that.”9 Reynolds said that no additional money would have been required, only changes to the statute that created ISFA. Still, Reinsdorf and Einhorn were naturally reluctant to leave their fate exclusively to the Illinois legislature at the risk of killing the chance the Florida legislature might appropriate the $30 million to accelerate the dome’s readiness for Opening Day. An unnamed team official declared, “They wanted us to cut off one leg in exchange for a promise that Springfield would try and give us another. … That’s not good business.”10

Despite the impasse, Thompson rallied Sawyer as well as legislative leaders from both parties to support the deal. He also cajoled Reinsdorf and Einhorn into releasing a statement on May 11, 1988, that the White Sox would stay if the legislature approved the deal. Thompson proclaimed, “Chicago deserves to keep the White Sox and the White Sox want to stay.”11 The terms of the agreement included provisions related to rent reductions if attendance thresholds were not met; splits in concession and parking revenues; increasing the bond authorization to $150 million (just in case); and penalties if the ballpark was not ready by the 1991 season. Democratic Senate President Philip Rock supported the deal but cautioned, “I told the governor I thought it would be very difficult to pass.”12 In the delicate game of playing off two states against each other, Reinsdorf and Einhorn managed to make missteps that irritated both. The day after declaring their intent to stay if the Illinois legislature approved the deal, Reinsdorf and Einhorn met with Florida legislators seeking a promise to move if they approved the $30 million package. Governor Martinez expressed irritation at having appeared in front of cameras wearing a White Sox jersey as the two announced their conditional intent to stay in Illinois.13

During the second half of May, the situation appeared to swing toward St. Petersburg. The Florida House voted 66 to 38 to approve the $30 million package on May 25. Meanwhile in Illinois, Thompson attended one meeting of Republican legislators with some donning blue Cubs caps and others wearing Cardinals red. Also, with Thompson pushing for an income-tax increase to fund education and public-health initiatives, the White Sox proposal became an even hotter political potato. Although the White Sox bill required no additional revenue, legislators were concerned about the optics of voting to help a baseball team without funding other important public-policy initiatives. Reinsdorf advised fellow baseball owners of his situation during the American League meetings in San Francisco on May 31. He commented afterward, “I’m still hopeful we can stay. But now it’s out of our hands. It’s up to the legislature.”14 With several AL teams facing challenging ballpark situations of their own, it seemed unlikely the owners would stand in the way of the White Sox relocating to Florida.

There appeared to be a brief respite from the relocation threat when the Florida Senate initially failed to act on the Suncoast Dome bill. On June 2, with the end of the session approaching, a Florida Senate committee cut the $30 million proposal in half. From his perspective at ISFA, Reynolds cautioned against assuming a weakening in the White Sox position. He believed a lease agreement was imminent, and added that “[i]f the people in Springfield don’t support it, then the Sox will leave town.”15 As the two states maneuvered over the White Sox, Chicago Tribune columnist Mike Royko started a “personal war” on Florida.16 Noting that 2 million Illinoisans visited Florida each year, he declared residents of the latter “lousy ingrates” and labeled St. Petersburg “an overgrown hick town.”17 Royko encouraged readers to mail a white sock to St. Petersburg Mayor Robert Ulrich; several hundred would oblige. With the Florida legislative session extended a few days to finalize the state budget, St. Petersburg advocates cobbled together the votes on June 7 to pass the $30 million bill. St. Petersburg Assistant City Manager Rick Dodge gushed, “It’s a wonderful invitation for the Chicago White Sox to become the Florida White Sox.”18 Reinsdorf and Einhorn issued their own anodyne statement: “Florida’s political leaders have made a progressive statement to bring major-league baseball to their state by passing this legislation. Their commitment is most impressive.”19

Back in Illinois, the likelihood of something similarly “impressive” seemed to diminish by the day. In addition to the generally tepid legislative reaction, Sawyer faced pressure as he looked to the 1989 Chicago mayoral election. Sawyer had become mayor upon Harold Washington’s death in December 1987, and his position within the African-American community was not assured. The fact that African-Americans would be disproportionately displaced through condemnation proceedings in the South Armour Square neighborhood, an area near the current ballpark that would host the new one, provided an opening for political opponents to exploit. That Washington was understood to favor that location appeared not to matter. Sawyer’s aloofness during the negotiations was noted. Moreover, of 67 Democrats in the House majority (versus 51 Republicans), only six were understood to support the stadium plan.20 Support seemed similarly lacking among Republicans with Assistant House Minority Leader Gene Hoffman, who favored the package, adding, “I haven’t found much support for the stadium at all.”21

With a notable lack of support from the 32 Chicago-area House Democrats, Thompson prodded House Speaker Mike Madigan to bring his fellow Democrats into line. Thompson argued, “I think members of the General Assembly, especially the members from Chicago, who been dragging their feet and setting a poor example for their Downstate brothers, had better think very long and hard about whether they want to wear the jacket as the guys who lost the team.”22 Days later, Madigan announced he had 36 Democrats prepared to support the deal and challenged Thompson to find 24 GOP votes to ensure passage. The speaker pronounced, “If Governor Thompson can now convince the other legislative leaders and a comparable number of legislators from the other sectors, then we’ll be able to pass the bill and keep the White Sox in Chicago.”23 Not to take Thompson’s barbs lightly, Madigan added about the governor, “If he does his job, the White Sox will stay in Chicago. If he fails, the White Sox will leave.”24

Progress was slow going in the state Senate. GOP leader James “Pate” Philip claimed only eight of his minority 28-member caucus supported the plan; property-tax relief was a higher priority.25 Senate President Rock struggled to round up votes among the Democratic majority. In fact, some Democratic members had other ideas. One influential senator, William Marovitz, pushed a West Side complex that would house the Bears and White Sox, an idea with little appeal to the Bears.26 Another Democratic senator, Greg Zito, pushed a plan to authorize the sale of $60 million in Build Illinois bonds to purchase the team from Reinsdorf and Einhorn and then sell $10 shares to the public. Zito argued that his plan would provide the two with $40 million more than they paid for the team, and “[i]n light of the fact they portray themselves as good businessmen, they would be foolish to turn it down.”27 Marovitz mocked the plan, “I hope no one thinks this will solve the Sox problem with the stadium.” Nevertheless, the Senate approved Zito’s plan on June 23 by a 38-to-18 vote with everyone looking to the House to kill the idea.

ISFA’s leaders, Reynolds and executive director Peter Bynoe, continued to press for a realistic legislative solution. With the June 30 closing of the legislative session approaching, new complications emerged. For one, the lease remained unsigned. Without a signed lease, there would be nothing to offer the legislature. Thompson summarized the dilemma, “If there is no lease, then there will be no stadium. If there is no stadium, they’ve said they will go to Florida. It’s that simple.”28 Additionally, efforts to effect an income-tax increase collapsed. Rock noted the dilemma facing legislators: “The perception would be that we have left the kids and the university systems bereft of what they need and yet we are affording a subsidy for professional sports. It’s just not going to equate.”29 Although Thompson and Madigan traded barbs – with Thompson referring to the “do-nothing legislature”30 – both men agreed that a signed lease was a prerequisite for any passage. Thompson argued, “If the White Sox want to stay in Chicago, they have it within their power to do that by signing a lease.”31 The White Sox relented and signed the lease on June 29, but also had a backup plan with St. Petersburg ready to take effect on July 1 if the legislature failed to act.32 Reinsdorf defended the backup plan: “It would not be prudent for us to not have a backup waiting in the wings.”33

With the arrival of June 30, the prospects for keeping the White Sox in Illinois appeared bleak. One Chicago Democratic representative lamented, “The income tax had to be there. But it’s not, and Florida is going to get the White Sox.”34 Thompson continued to emphasize the revenue neutrality of the plan in relation to the 1986 deal and the exclusivity of this legislation in relation to those public services that went unfunded.35 With the session in its final hour, Thompson and Madigan got to work on the floor of the Illinois House. In “an animated display of political arm-twisting,”36 Madigan pushed three more Democrats to vote for the proposal and Thompson garnered six more GOP votes. Madigan implored the chamber, “There are risks, but there is an upside. Let’s keep the Sox in Chicago.”37 In the end, minutes after passing the Illinois Senate 30 to 26, the White Sox stadium bill passed the Illinois House by a 60-to-55 vote. The time of the vote became the subject of legend. The Illinois Constitution required that the session end at midnight. The published roll of the vote read 12:03 A.M., which would have required a supermajority for passage, but Madigan noted, “By my watch, it was 11:59.”38

Despite passage, there remained several steps to complete to consummate the deal. Specifically, ISFA was required by the lease agreement to acquire 80 percent of the necessary land by October 15. To obviate political concerns, Sawyer announced plans to meet with neighborhood residents and conceded, “I’m not going to suggest that anybody is going to enjoy losing their homes.”39 Further, ISFA faced significant financial penalties if the ballpark was not ready for the 1991 season. Flanked by Reinsdorf, Einhorn, and Sawyer, Thompson signed the legislation behind home plate at Comiskey Park on July 6. The governor announced, “I want to send the message that Chicago is most American of all cities and Illinois is the most American of all states.”40 Regardless of Chicago’s status among American cities, it would remain both an American League city and a two-team major-league city. St. Petersburg would wait until 1998 before the Tampa Bay Devil Rays began play in what was then called Tropicana Field.

JOHN BAUER resides with his wife and two children in Parkville, Missouri, just outside of Kansas City. By day, he is an attorney specializing in insurance regulatory law and corporate law. By night, he spends many spring and summer evenings cheering for the San Francisco Giants and many fall and winter evenings reading history. He is a past and ongoing contributor to other SABR projects.

Notes

1 The ballpark was known as White Sox Park when it opened in 1910. It became Comiskey Park in 1913.

2 Bob Verdi, “Will Sox Have Their Day in the Sun (Coast)?” The Sporting News, April 11, 1988: 5.

3 Robert Davis, “St. Pete Longs to Be Big League,” Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1988: sec. 3; 1, 3.

4 Ibid.

5 “Chisox Eye Al Lang,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1988: 25.

6 Jerome Holtzman, “Thompson Tells Sox He’ll Do All He Can,” Chicago Tribune, May 1, 1988: sec. 3; 3.

7 Ibid.

8 John Kass, “Thompson Jumps Into Sox Stadium Fray,” Chicago Tribune, May 3, 1988: sec. 1; 1.

9 Kass, “State Halts Talks with Sox,” Chicago Tribune, May 10, 1988: sec. 1; 1.

10 Kass and Tim Franklin, “Thompson Tries to Revive Sox Deal,” Chicago Tribune, May 11, 1988: sec. 2; 1, 9.

11 Kass and Daniel Egler, “Sox Will Stay if Legislature OKs Proposal,” Chicago Tribune, May 12, 1988, sec. 1; 1.

12 Ibid.

13 Kass and Egler, “Sox Owners Hold Talks in Florida,” Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1988: sec. 2; 1, 2.

14 Holtzman, “At Least Reinsdorf and Einhorn Have AL Owners’ Support,” Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1988: sec. 4; 3.

15 Kass, “Florida Legislators Lobbying to Lure White Sox,” Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1988: sec. 2; 1.

16 Mike Royko, “Look Out Florida: This Means War,” Chicago Tribune, June 6, 1988: sec. 1; 3.

17 Ibid.

18 “Florida Legislature Approves $30 Million to Lure Sox,” (Springfield, Illinois) State Journal-Register, June 8, 1988: 18.

19 Kass, “Florida Lawmakers OK Sox Funding Bill,” Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1988: sec. 2; 1.

20 Kass, “Florida Legislators.”

21 Kass, “Sox Owners in Pitch to Legislators,” Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1988: sec. 2; 1.

22 Ibid.

23 “Madigan: Democrats Will Back Proposal to Keep Sox in Illinois,” State Journal-Register, June 11, 1988: 15.

24 Ibid.

25 Kass and Egler, “Progress Seen on Sox Stadium Deal,” Chicago Tribune, June 17, 1988: sec. 2; 3.

26 Ibid.

27 Doug Finke, “New Legislation Could Put White Sox in State’s Hands,” State Journal-Register, June 24, 1988: 19.

28 Kass, “Unsigned Lease May Doom White Sox Bill,” Chicago Tribune, June 26, 1988: sec. 2; 2.

29 “Tax Increase May Doom Aid for White Sox,” State Journal-Register, June 29, 1988: 27.

30 George Papajohn and Egler, “Governor Fears Tax-Hike Loss,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1988: sec. 1; 1.

31 Egler and Kass, “Governor and Madigan Agree on Need for Sox Stadium Lease,” Chicago Tribune, June 28, 1988: sec. 2; 2.

32 Egler and Kass, “Rock Holds Little Hope for Sox,” Chicago Tribune, June 29, 1988: sec. 1; 1.

33 Finke, “Sox Owners Agree to Lease, Await Stadium Package,” State Journal-Register, June 30, 1988: 22.

34 Kass and Egler, “Sox Sign Lease, but Deal May Be Doomed,” Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1988: sec. 1; 1.

35 Finke, “Sox Owners.”

36 Kass and Egler, “Bipartisan Rally Pushes Deal Through,” Chicago Tribune, July 1, 1988: sec. 1; 1.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Kass and Cheryl Duvall, “Mayor Will Visit Site of Stadium,” Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1988: sec. 2; 1.

40 “Thompson: We Are a Two-Team City,” State Journal-Register, July 7, 1988: 17.