Alias ‘Chick Arnold’: Chick Gandil’s wild west beginnings

This article was published in the SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee’s June 2020 newsletter.

Chick Gandil (top row, 3rd from left) was a fan favorite early in his baseball career, including here in 1907 in Mexico, where he was known as “Chick Arnold.” He played for a team sponsored by the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company and worked as a boiler maker between games. He also distinguished himself in the boxing ring on some nights. (Photo: Leman Saunders)

Chick Gandil, who helped instigate the Black Sox Scandal, is remembered best as a rough-and-tough baseball rogue who rarely got along with teammates or opponents until his career ended in disgrace. In his early days, however, he was quite a popular player everywhere he played — even when using an alias. As a teenage phenom, Gandil’s pursuit of glory took him all over the southwestern United States and across the border into Mexico, from the baseball field to the boxing ring, until he reached the major leagues.

Most sources indicate that Arnold “Chick” Gandil grew up in the Bay Area and attended high school there.1 But after a brief stay in San Francisco in the early 1890s, the Gandil family moved to Seattle2 by the turn of the century and then to Southern California, where Chick began playing baseball seriously as a teenager.

There are a few mentions of the Gandils living in Santa Barbara by January 1903.3 Two minor newspaper items are related to sports — not baseball, but bowling — with “A. Gandil” turning in some of the “best scores” at the Monarch bowling alleys.4

By 1904, when he was 16 years old, Gandil dipped his toes in the amateur baseball ranks. That year he played for a team sponsored by the Los Angeles Herald newspaper, playing many different positions throughout the year.5

In 1904, when Chick Gandil (top row, 2nd from left) was 16 years old, he played for a team sponsored by the Los Angeles Herald newspaper, playing many different positions throughout the year. (Los Angeles Herald, February 15, 1904)

It was reported that he spent two years in the Los Angeles City Baseball Association playing for the “Christopher nine” and while it is unclear just who Gandil was playing for in 1905, he is listed playing for the Christophers in January 1906.6 Then in March, Gandil jumped headfirst into semi-pro baseball when he left California to play in “Indian Territory.”7 As Gandil himself put it in a 1956 interview for Sports Illustrated he “hopped a freight bound for Amarillo, Texas, to play semipro.”8

Playing primarily third base for Amarillo, Gandil quickly became a fan favorite after reportedly hit a home run in his very first at-bat.9 The Amarillo club quickly fell onto hard times; by June, rumors of the team folding began to spread and the team’s primary investors met to discuss the future. Gandil left the team soon afterward.10

In later years as Gandil rose to stardom, Texas newspapers proudly laid claim to him. When Gandil made his major-league debut for the Chicago White Sox in 1910, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram ran a picture of Chick with a caption that read, “The big fellow is well known in Texas, not only in the cities of the Texas League, but also in other towns. At Amarillo, for instance, he has many friends who call him familiarly ‘Battle Axe.’ ”11 In 1912, the same paper published a picture of Gandil as a “Texas Product,” calling Amarillo his home, and claiming that is where he made his debut in baseball.12

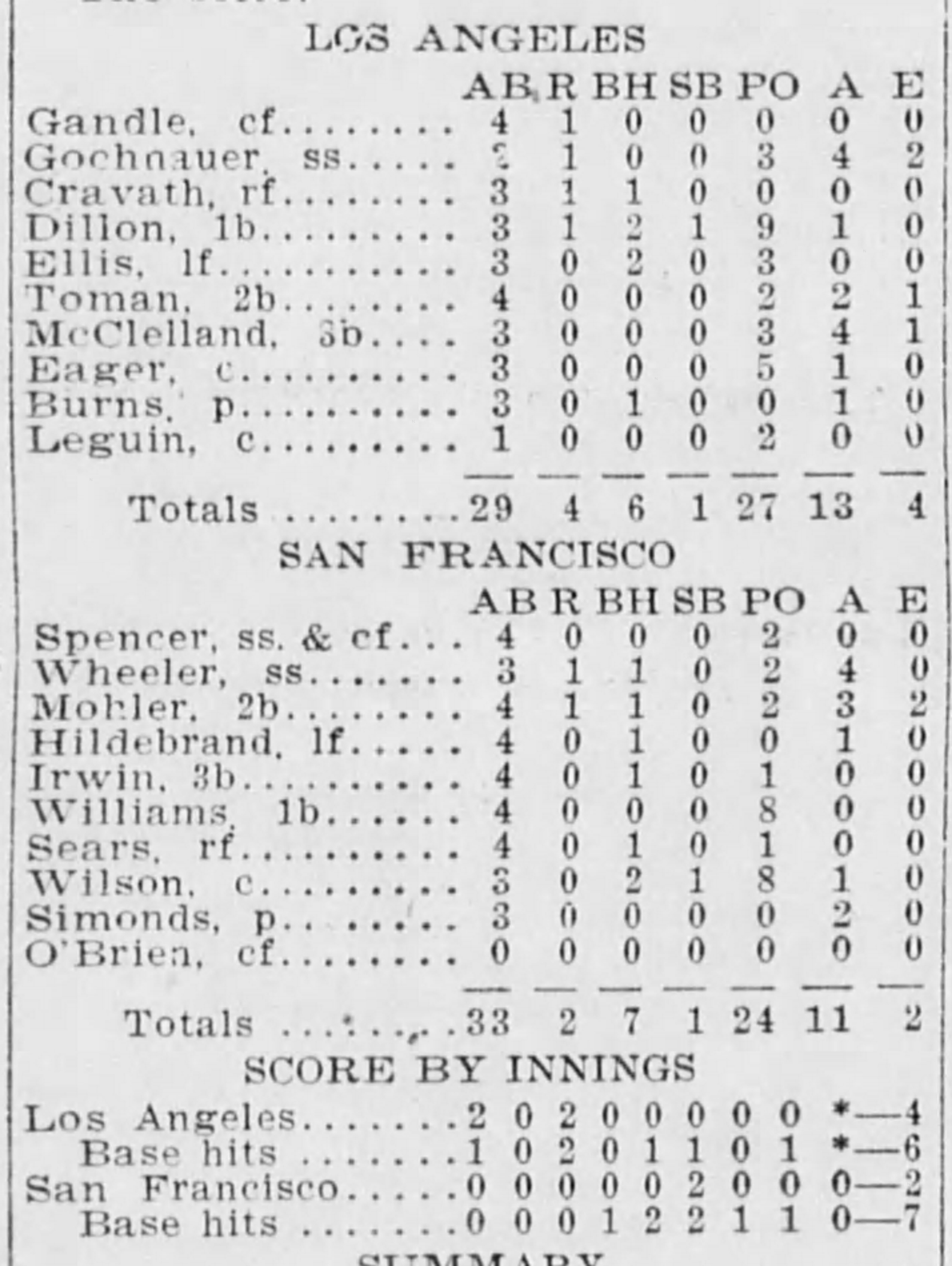

Gandil’s exact whereabouts after leaving Amarillo is unknown. There was one report which claimed he was bought by the Fort Worth Panthers in the Texas League and was let go due to fighting with an umpire.13 Gandil does not appear in any games for the Panthers and he likely simply went back home once the team in Amarillo showed signs of financial problems. Back in California on July 18, Gandil was given an opportunity to play for the Los Angeles Angels of the PCL. “Gandle … a lad from Fort Worth, Texas league” was given a tryout in center field. He went hitless, but did reach on an error and scored a run.14 He did not record a putout in the field. The starting pitcher for the Angels that day was William “Red” Burns, who later became more well known by a new nickname — Sleepy Bill. How serendipitous that Gandil’s first professional game was as a teammate of the man who would later help end his professional career.

“Gandle” was given another tryout with a PCL team on August 8 for Fresno in a game played in L.A. against Portland. He had one pinch hit at bat in the fifth inning and did not reach base.15

Upon his return to the local diamonds of Los Angeles, Gandil took the opportunity to start playing under a new name: Chick Arnold. The reason for changing his name is open to speculation, but he would primarily use that name in baseball for the next three years until he returned to the PCL in 1909.

By October 1906, Arnold had secured a spot playing for the Los Angeles Hamburgers of the California Winter League.16 Chick primarily played outfield and a little first base for the Hamburgers, who continued on in the Southern State League for the 1907 spring season. Many future major-leaguers were also part of the league and Gandil sharpened his talents and began to stand out as a powerful hitter.

In July, the Hamburgers withdrew from the league because “a number of players have been taken in by various teams in the professional league.”17 Gandil was one of them as it was reported that “speedy bushers” Arnold and a pitcher named Cole from a San Diego team were leaving for Humboldt, Arizona.18 Gandil joined the Humboldt team for a big Fourth of July tournament in nearby Prescott.

During his time playing for the Hamburgers, “Arnold” caught the eye of the Pacific Coast League’s Portland Beavers, who offered him a tryout as an outfielder. Gandil hustled back to California and made an appearance on July 6 against the Los Angeles Angels. The “local busher” was called in to play center field late in the game and did not record a hit in his only at-bat. In his one fielding opportunity, he committed a two-base error when he misjudged a fly ball when it “should have been an easy out.”19 The day’s bigger story was a one-hit pitching gem by the Angels ace, “Red” Burns, who would go on to win 24 games that season.

Chick Gandil, age 18, made his Pacific Coast League debut in 1906 when he was given a one-game tryout in center field by the Los Angeles Angels. The Angels’ starting pitcher was William “Red” Burns — later known as Sleepy Bill. They would cross paths again later in the Black Sox Scandal. (Los Angeles Herald, July 19, 1906)

Back in Los Angeles again and still going by Arnold, Chick played one game for the Playa Del Rey team on July 7 against the San Diego Pickwicks, going 2-for-5 with a triple and a run scored in a 5-4 loss.20 The Pickwicks liked what they saw and signed Gandil the following day.

The San Diego Evening Tribune reported, “In signing Arnold, manager Palmer has secured probably the heaviest hitter in the Southern California league. He seldom strikes out and when he clouts the ball fairly usually sends it to the fence. His batting has brought him much favorable notice and last Friday the management at Portland offered to give him a tryout in right field this week.”21

It is unclear if Arnold ever played for the Pickwicks. On July 21, the Los Angeles Times reported “Arnold Gandil, known in baseball circles as ‘Chic’ Arnold … is now playing with the Humboldt, Ariz., team, in the Arizona State League.”22

To add more mystery to Chick’s departure, his father, Christian Gandil, took out an ad in the Los Angeles Times that ran on July 13:

“NOTICE – TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN, I will not be responsible for any debts my son Arnold, sometimes called Chic, may contract on or after this date, July 11, 1907. C. Gandil.”23

One can only speculate as to what might have led to this announcement needing to be published. But for all intents and purposes, Arnold “Chick” Gandil, alias Chick Arnold, had been fully emancipated from his family.

Arnold packed his bags and headed back to Arizona.24 With Humboldt, Chick played all over the field, including catcher and even pitching in relief in at least one game. On July 30 against Prescott, Arnold began the game as a catcher and relieved the Humboldt starting pitcher in the sixth inning. While Chick did hit a triple, he allowed three passed balls as a catcher and accounted for a wild pitch on the mound while striking out two in a 13-5 loss.25 Gandil also was loaned out to play a few games for the Prescott team in August.

In mid-August, Gandil and a teammate left for Mexico to play for the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company team and work as a boiler between games. Players in this league usually were given jobs in the towns where they played. The smelting plant in Humboldt and the railroad in Prescott appear to be the players’ most likely employers. Gandil reportedly went to Prescott “with the understanding that he would have employment with the railroad in order to secure his services on the baseball diamond”, but his quick departure to play and work in Cananea suggests that the railroad job did not pan out.26

In Cananea, Gandil was a popular player known for his hitting throughout the league. He also became a two-sport athlete, spending some nights in the boxing ring.

One highly publicized bout was against Tucson heavyweight Jack Bernal on September 17 in Cananea. Scheduled to go 20 rounds to decide the “heavyweight championship of Arizona and Sonora,” Chick, tipping the scales at 180 pounds, defeated the heavier Bernal in the third round thanks to his “superior reach and fast footwork.”27

The Bisbee Daily Review provided a thorough recap of the fight, with a round-by-round summary. A reported 400 people left the theater enthusiastic over the victory by “the big first baseman of the Cananea ball team.” Gandil landed a combination that knocked Bernal into his corner and “into his chair, where he took the count.” The newspaper concluded that “Bernal did not hit Arnold a good clean blow during the bout” and that he was “outclassed in all respects.”28

Bernal contested the decision upon his return to Tucson, telling the Tucson Citizen that he was “clearly entitled to [t]he decision, as he had the best of the contest.”29 This triggered a defiant response from Arnold who sent a letter to the Arizona Daily Star claiming “Bernal was not in the fight from the beginning to the end, and that he is willing to meet Bernal at any time he is ready for a purse of from $100 to $1,000.” He also said he would “meet Bernal in a six-foot ring to show him who it was that ran” and that he would “fight Bernal at 170 pounds … and if he does not knock him out in two rounds” that Bernal could “have all of the gate receipts.” It is unclear if Bernal took Gandil up on his rematch offer.

Gandil knocked around the Arizona State League throughout November. While Cananea was his primary team, he made an appearance playing in at least one game for Tucson and finished up the season playing for the team in Bisbee, Arizona.30

Gandil was well received by the fans and towns where he played, in part because he played for at least five different teams in the Arizona State League and thus easily recognized by all fans and because of his talent almost all of these teams jockeyed to secure his services in 1908. In the following years whenever Gandil made career advancements, the Arizona papers would brag about this “Arizonan” making good and how well liked he was in the towns he played in.

After learning of his signing with the White Sox in July 1909, the Arizona Daily Star heaped praise on Gandil, saying, “It is sincerely hoped by his many friends here that he will make good in a Chicago uniform next season.” A few weeks later, the paper praised Gandil’s talents and ties to Arizona under the headline “Former Arizonan Distinguishes Self.”31

Louisiana would be Gandil’s primary home for the 1908 season with the Shreveport Pirates of the Texas League. While with Cananea, Gandil primarily played at first base and that was the position he played in Shreveport. Still playing under his nom de plume of Arnold, Chick once again quickly became a fan favorite. Back in Arizona, the Bisbee Daily Review lamented his departure:

“There has been a faint, selfish hope in the hearts of several fans that the torpid atmosphere of Louisiana would make Chick Arnold long for the cool breezes of the mountains and cause him to throw off in his tryout with Shreveport, so that he could secure his release and shine again as Cananea’s star. … He has a whip like a Texas blacksnake, a lightning quickness of action when the ball gets in his territory-picking up low ones, pulling down high ones and gathering in wild throws like a school girl plucking daisies in the field. Whenever he faces the pitcher the ball generally raises the dust in a good safe spot, far from any fielder’s itching glove.”32

Gandil had a strong season in Shreveport that ended prematurely on August 15 with a leg injury while sliding into second base.33 By September, he was back in Cananea playing winter ball in Mexico again.34

In February 1909, the “strapping big fellow” arrived in California to play for the Fresno Giants of the outlaw California State League.35 Almost immediately, he found himself in turmoil — leading to his arrest after he jumped to a new team.

He played in a few practice games with the Giants before greater temptation lured him away. An agent from the PCL’s Sacramento Senators came to Fresno to secure players for the upcoming season. In the wee morning hours of March 20, under the watchful eye of Fresno club representatives suspicious of his intentions, Gandil and his wife, the former Fay Kelly, boarded a train bound for Sacramento. Gandil played in that afternoon’s game where he started the game-winning rally in the ninth inning with a single and scored the winning run.36

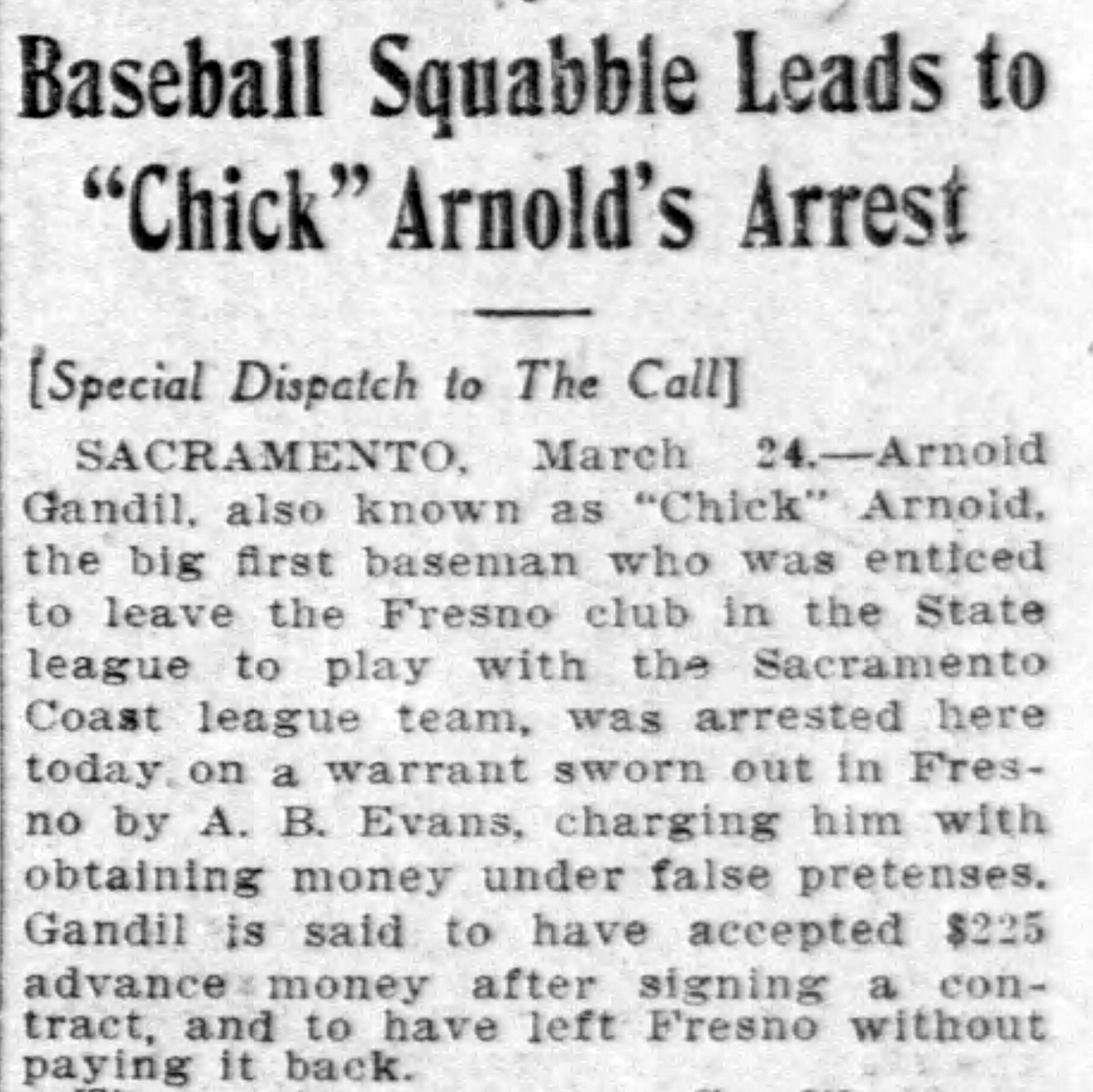

Gandil, called the “Human Frog” by a Fresno newspaper37, was not the first or last player to jump for the PCL, but his case was special. Fresno went after Gandil, claiming he had absconded with a $225 advance and with a “suit loaned him by the Fresno management to practice in.”38 Sacramento secretary John Inman denied these charges and claimed they had “made arrangements” with Fresno to cover any of Gandil’s expenses. He added there was “nothing underhanded about the deal” and that Gandil gave the Fresno club “due notice” of his intentions to leave the club.39

The situation escalated as a warrant was issued for Gandil’s arrest on March 24 for “obtaining money on false pretenses.” He quickly turned himself in and was bailed out by the Sacramento manager and a stockholder; Gandil went straight to the ballpark for practice.40

All of this took place while Gandil’s contract was still held by the Shreveport ballclub back in Louisiana. Sacramento worked hard behind the scenes, even enlisting the help and influence of American League President Ban Johnson, to make sure Gandil was not branded an outlaw.41 The matter was cleared up behind the scenes and the Fresno fiasco ended with Gandil reverting back to his given name for baseball purposes.

A contract dispute between the Fresno Giants of the outlaw California State League and the Sacramento Senators of the Pacific Coast League led to Chick Gandil’s arrest before

the 1909 season. Sacramento officials worked with American League President Ban Johnson to ensure Gandil remained eligible in professional baseball. (San Francisco Call, March 25, 1909)

In Sacramento, Chick went on to have his best and most consistent season with 212 hits, putting him among the contenders for the PCL batting title, and catching the eye of Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey who signed the 21-year-old first baseman in July and invited him to spring training in 1910.42

When Gandil returned to Fresno for a spring training game that spring, local fans had not forgotten about the “grasshopper” who had jumped their team, as Hugh Fullerton reported:

Chick Gandil, christened Grasshopper out here because he once jumped from Fresno into the Coast League, got his revenge yesterday by slamming four slashing drives, one a double through the infield, and he silenced the jeers of the crowd.

Fullerton also opined about the young prospect, “Comiskey is much encouraged. He says Gandil has no faults that cannot be corrected and he thinks he has found a first baseman.”43

It is hard to imagine now a teenager taking off on his own, riding trains, bouncing from town to town trying to make a living and chase his dream of becoming a ball player in an area not far removed from the days of the Wild West. By closely examining this time in his life it is easy to see how these formative years shaped a young Arnold Gandil not only into overcoming adversities to become a great player, but more importantly toughening up the teenager and helping shape him into the rough character he was later reported to be.

Notes

1 A 1914 Baseball Magazine profile of Gandil claims that the family left Minnesota for Berkeley, California, around 1890 and “have resided (there) ever since.” The article also says Gandil attended Oakland High School for two years and most biographical sources repeat these claims. However, there do not seem to be any records of Gandil attending the school. See: “’Chic’ Gandil, The Man Who Started the Famous ‘Seventeen Straight,’ ” Baseball Magazine, August 1914, accessed online at LA84.org.

2 1900 US Census, Ancestry.com. The 1901 and 1902 Seattle City Directories show Chick’s father, Christian Gandil, living in an apartment above his florist shop at the corner of 10th Avenue and E. Prospect Street in Seattle. In December 1902, a “C. Gandil” placed multiple ads in the Los Angeles Times for “garden work by the day.” Since Chick Gandil was playing baseball in Los Angeles in 1904 and Christian Gandil appears in the Los Angeles City Directory by 1905, it seems likely the entire family had moved to Southern California.

3 “Advertised Letters,” Santa Barbara Weekly Press, February 12, 1903. A list of names for Santa Barbara on February 9 includes Christian Gandil and Mrs. C. Gandil who was noted as being “foreign.”

4 “High Scores,” Santa Barbara Weekly Press, January 15, 1903; January 22, 1903.

5 “Heralds Win Again,” Los Angeles Herald, June 13, 1904; “Many Amateurs Play Fast Ball,” Los Angeles Herald, June 20, 1904.

6 “Many Men Join Professionals,” Los Angeles Times, July 21, 1907.

7 “Jud Smith is Obstreperous,” Los Angeles Times, March 25, 1906.

8 Melvin Durslag, “This Is My Story of The Black Sox Series,” Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956.

9 “Many Men Join Professionals.”

10 “Base Ball Team Re-Organized,” Amarillo Herald, June 22, 1906. A Los Angeles Herald article on July 9 mentions an “Arnold” playing left field for the Jevne Clerks in the Los Angeles County League, and this may possibly be Gandil, too.

11 “Dale Gear’s Student,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 20, 1910. The caption refers to Gandil’s time playing with the Shreveport Pirates of the Texas League in 1908 as well as his time with Amarillo.

12 “Chick Gandil, Texas Product, Is Washington’s First Sacker,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 2, 1912.

13 “Many Men Join Professionals.”

14 “Angels Turn Diamond Tables,” Los Angeles Herold, July 19, 1906.

15 “Fresnoites Fail To Make Stand With Giants,” The San Francisco Call, August 9, 1906.

16 “Many Men Join Professionals.”

17 “Hamburgers Out,” Los Angeles Times, July 2, 1907.

18 “Mr. Perkins Is Up Against It,” Los Angeles Herald, June 29, 1907.

19 “Angels Even Up With Portland,” Los Angeles Daily Herald, July, 7, 1907.

20 “Pickwicks Winner of Hard Fought Game,” San Diego Evening Tribune, July 8, 1907.

21 “Arnold is Signed by Manager Palmer,” San Diego Evening Tribune, July 9, 1907.

22 “Many Men Join Professionals.”

23 Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1907.

24 “Los Angeles Visitors,” Prescott Weekly Journal-Miner, July 17, 1907. The article notes that “C. Arnold” was one of three visitors arriving from Los Angeles. “Arnold” appears in a game report playing for Humboldt on July 21, with the home team winning 6-4 over Prescott.

25 “Prescott Takes Game From Greens,” Prescott Weekly Journal-Miner, July 31, 1907.

26 Prescott Morning Courier, August 10, 1907.

27 “Bernal Loses His Battle,” Tucson Citizen, September 17, 1907.

28 “Arnold Pounds Bernal To A Finish,” Bisbee Daily Review, September 18, 1907.

29 “The City News In Paragraphs,” Tucson Citizen, September 19, 1907: 5.

30 “Former Arizonan Distinguishes Self,” Arizona Daily Star, July 29, 1909. This article claims that Gandil “late in the season of 1907 … joined the Bisbee club and was benched because of incompetency.” But he did in fact play in several games for Bisbee in late November-December near the end of the season. One box score shows Arnold going 0-for-4 in the final game between Bisbee and Phoenix on December 1.

31 “Chick Arnold Goes Into Fast Company,” Arizona Daily Star, July 8, 1909; “Former Arizonan Distinguishes Self.”

32 “First Game At Douglas With Cananea,” Bisbee Daily Review, April 5, 1908.

33 “Baseball Today,” Shreveport Times, August 16, 1908.

34 “Regulars Take One Game Out of Series,” Daily Arizona Silver Belt, September 29, 1908.

35 “Pitchers Joe Bills And Lutes Are Here,” Fresno Morning Republican, February 24, 1909.

36 “’Chic’ Arnold Jumps to Sacramento Coasters,” “Chic Arnold Wins Game With Stick,” Fresno Morning Republican, March 21, 1909.

37 “Chic Arnold, Human Frog First Sacker,” Fresno Morning Republican, March 21, 1909. At least two other players reportedly jumped from Fresno to Sacramento that spring.

38 “’Chic’ Arnold Jumps to Sacramento Coasters,” Fresno Morning Republican, March 21, 1909. On March 24, the paper claimed Gandil had broken into the clubhouse to retrieve his suitcase which contained his uniform.

39 “Fresno, The Loser, Is Squealing,”, Sacramento Bee, March 22, 1909.

40 “First Baseman Gandil Has Some Troubles,” Sacramento Star, March 24, 1909.

41 “All Claim To Arnold Waived,” Fresno Morning Republican, March 29, 1909.

42 “Unofficial Averages of Coast League Batting just Closed,” Los Angeles Herald, November 7, 1909.

43 “Chat of the Game,” Sacramento Bee, March 16, 1910.