This is the central thesis of Eight Men Out: Charles Comiskey’s “ballplayers were the best and were paid as poorly as the worst,” as Eliot Asinof wrote. That couldn’t be further from the truth. We can’t climb into the heads of the Black Sox to know exactly why they threw the World Series. But the players themselves rarely claimed, as Asinof did, that it was because of Comiskey’s low salaries or poor treatment — and we now have accurate salary information to back that up. Newly available organizational contract cards at the National Baseball Hall of Fame show that the White Sox’s Opening Day payroll of $88,461 was more than $11,500 higher than that of the National League champion Reds, and several of the Black Sox players were among the highest-paid at their positions. If they did feel resentment at their salaries under the reserve-clause system, so did players from 15 other major-league teams. The scandal was much more complex than disgruntled players trying to get back at the big, bad boss.

Further reading

- A summary of the Black Sox Scandal — what we know now, by Bill Lamb

- 1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox, by Bob Hoie (use password “McFarland” to open PDF)

- 1919 American League salaries and payrolls, by Jacob Pomrenke

- Charles Comiskey’s SABR biography, by Irv Goldfarb

One of the most dramatic scenes in Eight Men Out is when White Sox ace Eddie Cicotte tries to collect a $10,000 bonus he says Charles Comiskey promised him if he won 30 games. (In the book, this story occurs in 1917; in the film, 1919.) The incident is seen as the catalyst for Cicotte’s involvement in the fix — but there is no basis of truth to the story. Other White Sox players did have small performance bonuses in their contracts. For example, Lefty Williams was paid a $500 bonus for winning 20 games in 1919. In any event, Cicotte and Chick Gandil were already conspiring with gamblers to fix the World Series several weeks before Comiskey would have had the chance to renege on a bonus payment. And if Cicotte had pitched better in the pennant clincher, he would have earned his 30th win regardless.

Further reading

- How cheap was Charles Comiskey? Salaries and the Black Sox, by Michael Haupert

- An examination of Black Sox player salary histories, by Bob Hoie

- September 24, 1919: White Sox walk off to the World Series, by Jacob Pomrenke

- Eddie Cicotte’s SABR biography, by Jim Sandoval

Arnold Rothstein, known as “The Big Bankroll,” was credited as the mastermind of the plot by his henchman Abe Attell in a self-serving interview with Eliot Asinof years later, but it may have still gone through even without the involvement of the New York kingpin. Fixing the World Series was a total “team” effort and the White Sox players did most of the heavy lifting. Chick Gandil and Eddie Cicotte, separately and together, first approached Sport Sullivan, a prominent Boston bookmaker, and Sleepy Bill Burns, a former major-league pitcher, to get the fix rolling. Then they began recruiting their teammates in several meetings before the World Series. Rothstein eventually did get involved, but he was far from the only underworld figure to play a role.

Further reading

- Sport Sullivan’s SABR biography, by Bruce Allardice

- Sleepy Bill Burns’s SABR biography, by Stephen V. Rice

- Chick Gandil’s SABR biography, by Daniel Ginsburg

- Beyond Eight Men Out: The Des Moines Connection to the Black Sox Scandal, by Ralph Christian

- Find more SABR bios for Billy Maharg, Nat Evans, Carl Zork, the Levi brothers, and other gamblers

It’s easy to believe the Chicago White Sox players could be the targets of an Al Capone-style takeout by gamblers if they didn’t hold up their end of the fix. But Eliot Asinof said on multiple occasions, first in his Black Sox-related book Bleeding Between the Lines and then in subsequent interviews, that he invented the hitman character on the advice of his publisher to guard against copyright infringement. An attorney recommended that he do so in case anyone used the name “Harry F.” in future books and articles without citing his work; many writers have done just that. But there is little evidence to substantiate the claim that Williams’s life was in danger. The primary source is an anecdote by a neighbor boy — first told four decades after the fact — who claimed Lefty’s wife once told him the pitcher had been threatened.

Further reading

- Lefty Williams’s SABR biography, by Jacob Pomrenke

- Rare film footage of 1919 World Series discovered in Canadian archive

It’s impossible to understand the Black Sox Scandal without knowing how deeply the game was intertwined with America’s gambling-friendly culture at that time. Baseball’s powers-that-be mostly turned a blind eye to — and in some cases, implicitly encouraged — the corruption and game-fixing of the early twentieth century. Veteran first baseman Hal Chase was caught red-handed bribing teammates and opponents alike in 1918, but he was whitewashed by the National League. Future Hall of Famers Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker were accused of fixing a Tigers-Indians game just one week before the 1919 World Series. A major game-fixing scandal erupted in the Pacific Coast League in 1919, as well. As the historians Dr. Harold and Dorothy Seymour wrote, “The groundwork for the crooked 1919 World Series, like most striking events in history, was long prepared. The scandal was not an aberration brought about solely by a handful of villainous players. It was a culmination of corruption and attempts at corruption that reached back nearly twenty years.”

Further reading

- The Fix Is in: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals, by Daniel Ginsburg

- ‘Playing Rotten, It Ain’t That Hard To Do’: How the Black Sox Threw the 1920 Pennant, by Bruce Allardice

- Hal Chase’s SABR biography, by Martin Kohout

- Baseball’s Bans and Blacklists: The Complete Story, by John Thorn

- The Bad News Bees: Salt Lake City and the 1919 Pacific Coast League Scandal, by Larry Gerlach

- Find SABR bios for Joe Gedeon, Lee Magee, Rube Benton, Gene Paulette and other players banned from baseball

Who had “guilty knowledge” about the 1919 World Series fix? Just about everyone in the sport’s inner circle, including White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, who admitted in a 1930 interview that he heard reports about the fix before any games were played. He sent manager Kid Gleason to interview a gambler immediately after the World Series and hired detectives to follow the suspected players during the offseason. But Comiskey and other baseball officials allowed most of the 1920 season to be played without publicizing what they had learned. A diligent investigation by reporters such as Hugh Fullerton, James Crusinberry, and a small Chicago-based gambling trade publication called Collyer’s Eye — the first to publicly name the players involved — helped expose the corruption and grease the wheels for a full legal inquiry.

Further reading

- Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded, by Gene Carney

- Under Pallor, Under Shadow: The 1920 American League Pennant Race That Rattled and Rebuilt Baseball, by Bill Felber

- Charles Comiskey’s Detectives, by Gene Carney

- The Black Sox Scandal and the 1919-20 Offseason, by Jacob Pomrenke

- The Boxer, the Ballplayer, and the Great Black Sox Manhunt, by Jacob Pomrenke

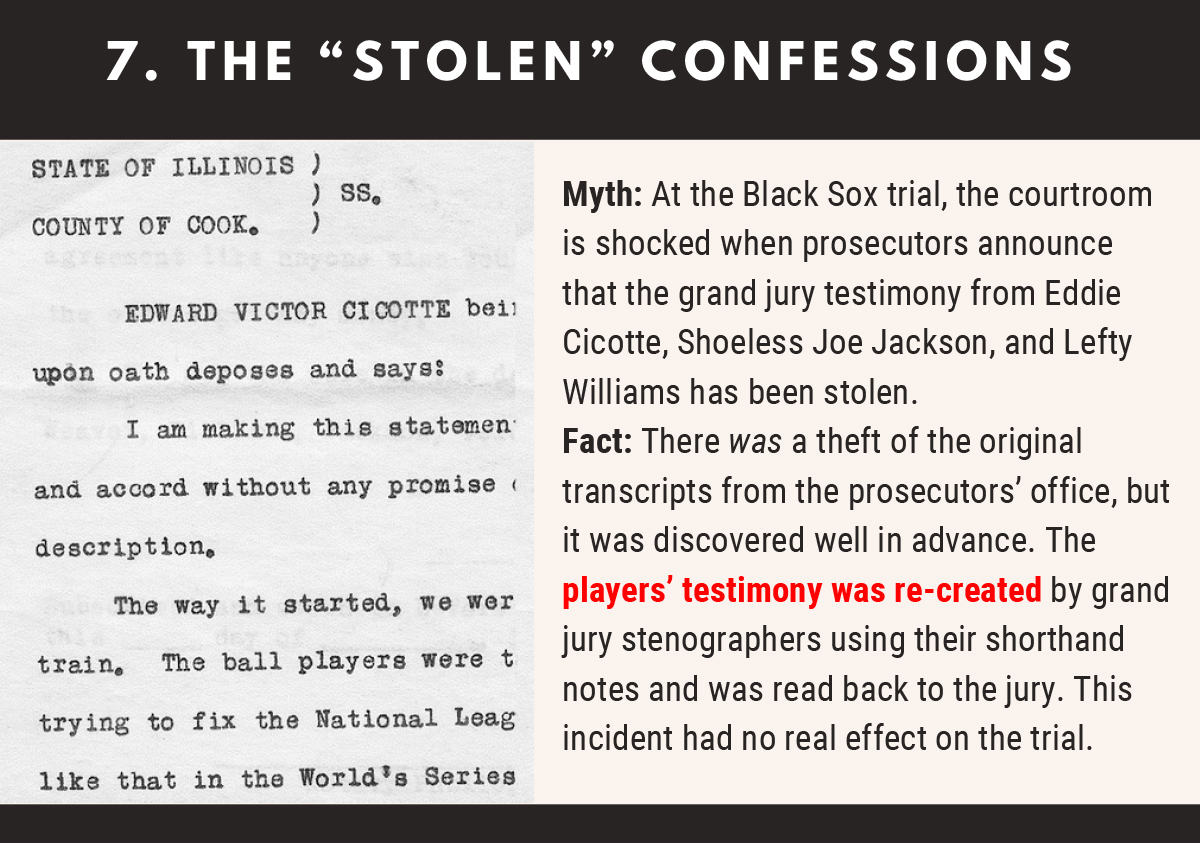

The Black Sox criminal trial, which resulted in the acquittal of the players, is often depicted as an example of Chicago-style corruption and shady courtroom shenanigans. The theft of key files, including the players’ grand jury testimony transcripts, from the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office was dramatized in the film Eight Men Out, leading to baseless speculation on whether the White Sox lawyers had joined forces with gambler Arnold Rothstein to help out the players or if the trial’s outcome had been “prearranged.” But the theft was a minor incident that played no significant role in the jury’s decision.

Further reading

- Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation, by Bill Lamb

- Jury Nullification and the Not Guilty Verdicts in the Black Sox Case, by Bill Lamb

- An Ever-Changing Story: Exposition and Analysis of Shoeless Joe Jackson’s Public Statements on the Black Sox Scandal, by Bill Lamb

- The Enduring Myth of the ‘Stolen’ Black Sox Confessions, by Jacob Pomrenke

- Eddie Cicotte on the Day That Shook Baseball, by Gene Carney

- Shoeless Joe Jackson’s SABR biography, by David Fleitz

When Eliot Asinof went looking for the surviving Black Sox in the early 1960s, he encountered resistance from almost every ballplayer he found; Happy Felsch was one of the few exceptions and one of his main sources for Eight Men Out. Asinof attributed their reluctance to talk to the stigma that everyone involved, even the innocent players, supposedly felt about the 1919 World Series. But that wasn’t the case at all. Some of the players expressed remorse (especially Eddie Cicotte and Felsch), while others remained defiant or claimed innocence. The players did not, as is commonly believed, hang their heads in shame and “drop out of sight” or “quietly vanish” after they were banned from baseball.

Further reading

- No ‘Solid Front of Silence’: The Forgotten Black Sox Scandal Interviews, by Jacob Pomrenke

- Click here for a list of all known interviews with 1919 World Series participants

- Happy Felsch’s SABR biography, by Jim Nitz

- Saying It’s So: A Cultural History of the Black Sox Scandal, by Daniel A. Nathan

MORE EIGHT MEN OUT MYTHS

- Online appendix: Click here for a comprehensive list of known errors in the Eight Men Out book and film, compiled by Bill Lamb

DIG DEEPER

The Black Sox Scandal is a cold case, not a closed case.

The Black Sox Scandal is a cold case, not a closed case.

We hope this online guide, produced by members of SABR’s Black Sox Scandal Research Committee, helps provide you with a more complete understanding of the 1919 World Series and inspires you to dig deeper and learn more.

A lot of new information has been uncovered in recent years that has changed our collective knowledge of the Black Sox Scandal and its aftermath. All of these new pieces to the puzzle have provided definitive answers to some old mysteries and raised other questions in their place.

It’s a story that continues to fascinate baseball fans, writers, and researchers all over the world. The Black Sox Scandal continues to be a relevant part of the sports world in the 21st century, especially as Major League Baseball begins to open its doors to legalized betting 100 years later. One hundred years after the 1919 World Series, we’re still learning more every day about what happened on and off the field.

Here are more ways to explore this fascinating story:

- Centennial Symposium: Listen to highlights from the SABR Black Sox Scandal Centennial Symposium on September 28, 2019, at the Chicago History Museum

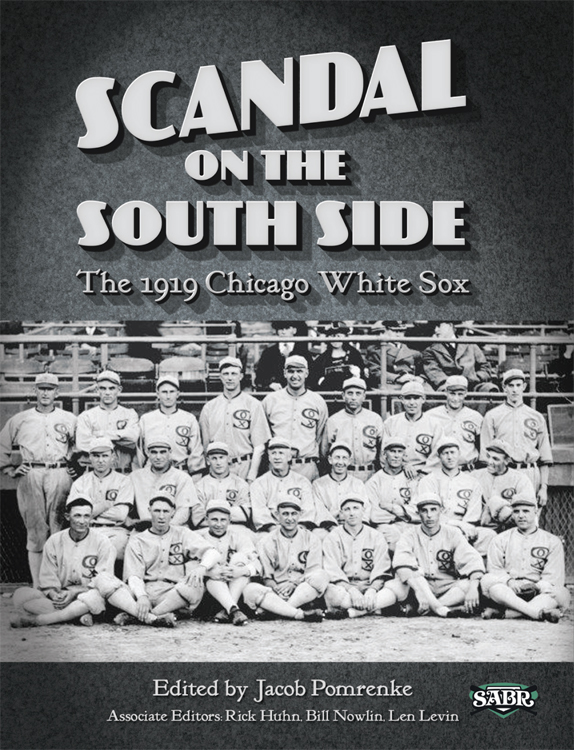

- Buy the book: Get your copy of Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox today; SABR members can download a free e-book copy or get 50% off the paperback edition

- Sign up for updates: Learn more about joining SABR’s Black Sox Scandal Research Committee or sign up for our online discussion group