Bonus Performance: Babe Ruth and His 1921 Contract

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2021 as part of the SABR Century 1921 Project.

In early January 1920, approximately one week after the news broke that the Red Sox had sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees, the New York Times wrote, “The famous Ruth is a personage of considerable worth to the lessee of his services; and, however much money the New York baseball club may have paid for him, it will doubtless make an adequate profit.” The newspaper went on to note that though the Red Sox were unimpressive in 1919, “all along the road [Boston] drew crowds who came out to see Ruth ‘hit ’em out of the lot.’”1

In early January 1920, approximately one week after the news broke that the Red Sox had sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees, the New York Times wrote, “The famous Ruth is a personage of considerable worth to the lessee of his services; and, however much money the New York baseball club may have paid for him, it will doubtless make an adequate profit.” The newspaper went on to note that though the Red Sox were unimpressive in 1919, “all along the road [Boston] drew crowds who came out to see Ruth ‘hit ’em out of the lot.’”1

Indeed, Ruth went on to earn fame and fortune of gargantuan proportion for both himself and the Yankees. He became the most famous athlete of his generation, the highest-paid baseball player and a marketing bonanza, and the source of great riches and on-field success for the Yankees.2

In 1919, the year before he joined the Yankees, Ruth clouted the then unheard-of total of 29 home runs. He out-homered 10 other teams that year, as well as his own Red Sox teammates, who combined for four round-trippers. In doing so, he broke Ned Williamson’s long-standing record of 27 home runs in a single season.3 The following year, his first in New York, he nearly doubled his record-setting total, belting 54, more than every other team but the Philadelphia Phillies.4

A SEASON FOR THE AGES

Ruth saved arguably his best career performance for 1921, a season in which his 59 home runs led the league for the fourth straight year, and he broke the single-season mark for the third consecutive year. However, in a sign of the changing nature of the game, he managed to personally out-homer only half the league’s teams.

Ruth’s 1921 season may be the greatest hitting exhibition in baseball history. In 693 trips to the plate, Ruth led all players with 177 runs scored, 59 home runs, 168 runs batted in, 145 walks, a .512 on-base percentage, an .846 slugging percentage, and 457 total bases. He finished in the top ten in batting average (.378, good for fourth), doubles (44, second only to Tris Speaker’s 52), and triples (16, ninth) among his 204 hits (tied for eighth). Just for good measure, he stole 17 bases and won two games in two mound appearances.

And Ruth didn’t just lead the league in all those hitting categories. He dominated it. He hit more home runs than eight other teams that year, and equaled the homer output of one more. (Brooklyn’s lineup matched his 59 homers.) He hit 35 more home runs than Ken Williams and Bob Meusel, who tied for second, and nearly 10 times as many as the average major leaguer hit that year. His 177 runs scored were 45 percent more than runner-up Jack Tobin’s 122, and 140 percent more than the league average. His .846 slugging average was 32 percent higher than the nearest rival (Rogers Hornsby, .639), and more than double the league average.

Ruth helped the Yankees win their first pennant and draw 1,230,696 fans, down slightly from the team record 1,289,422 who came out to see the Babe in his inaugural year in pinstripes.5 The one crown he did not wear was that of salary king. For the only time in his Yankee career, someone else had a higher base salary. Ty Cobb was paid the princely sum of $25,000 in 1921 to serve as Detroit’s player-manager. Meanwhile, Ruth was playing in the final year of his contract, which called for a base salary of $10,000 plus a $10,000 signing bonus. Despite the higher base salary, Ruth actually out earned Cobb when the final calculations were made at season’s end.

RUTH’S 1921 CONTRACT

Before he ever donned Yankee pinstripes, Ruth had already renegotiated the remaining two years of his three-year Red Sox contract with his new employers. Ruth was no stranger to haggling over his contract, and was certainly neither naïve about his value nor shy about making it known. After all, he had negotiated a hefty three-year, $30,000 contract with the Red Sox before the 1919 season. The $10,000 annual salary paid him four times more than the average player earned, and the multiyear pact was a rarity. In 1919 fewer than 15 percent of major-league contracts covered more than one year, and virtually all of them contained the dreaded 10-day clause, which allowed a team to cancel the contract on 10 days’ notice.6 Free agency has changed the nature of contracts. Today they are all guaranteed, and the average team has one-third of its roster on multiyear contracts, some extending more than a decade into the future.7

The 1919 season was barely in the books when Ruth began making noise about wanting to renegotiate his contract. When his sale to the Yankees was announced, he renewed his demands for a new deal, and also demanded a share of the sale price. While he did not get the latter, he did get the former. The Yankees doubled his annual salary by adding a $10,000 signing bonus to each of the remaining two years of his contract. Anticipating just such a demand from Ruth, they had made provisions with the Red Sox to cover a salary increase, resulting in the Red Sox paying $5,000 of Ruth’s salary each of those years.8

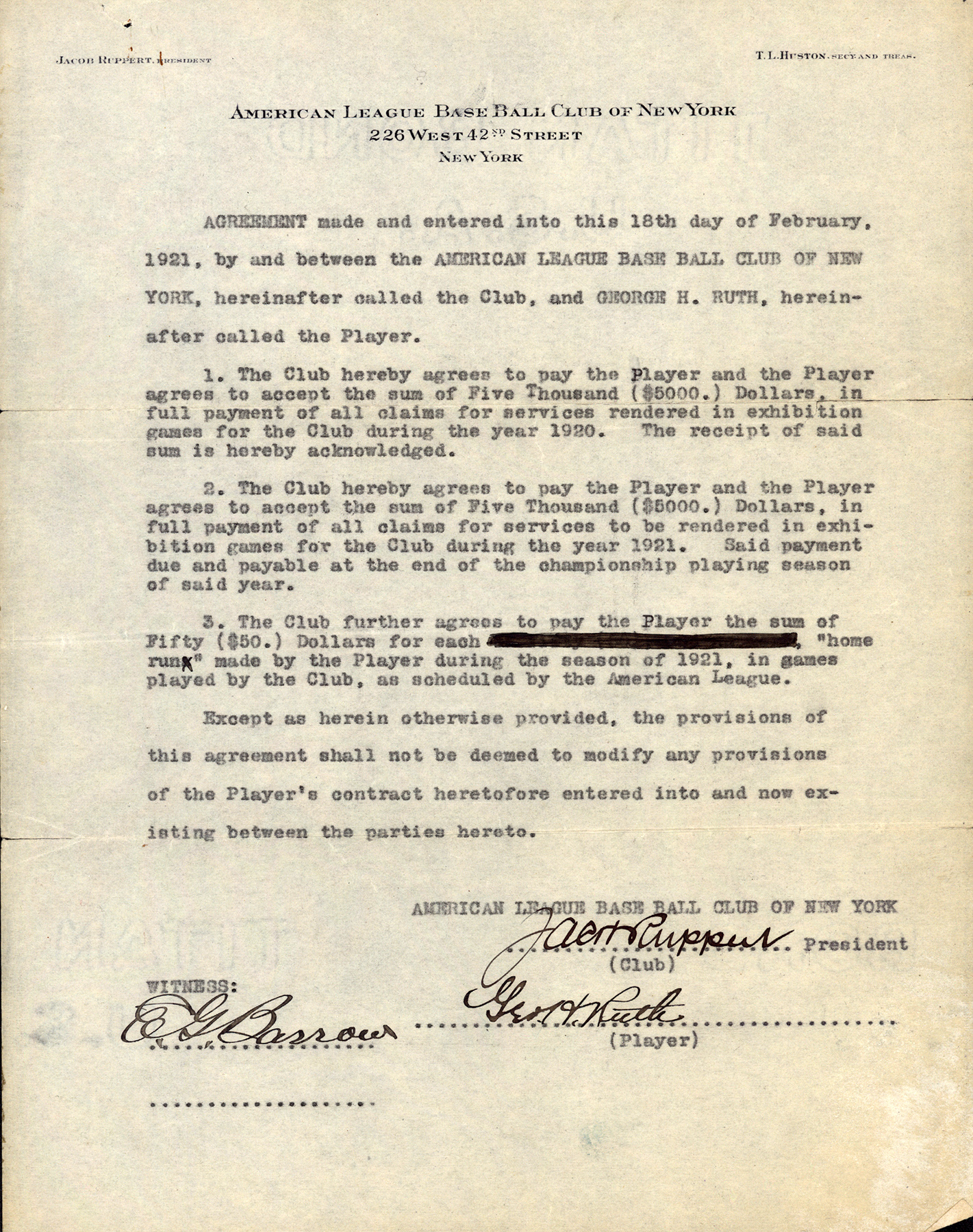

As fabulous as 1920 was for Ruth, 1921 would be even better. On February 18 of that year the Yankees and Ruth agreed to a contract addendum that would pay Ruth a $5,000 bonus for playing in exhibition games, plus a retroactive $5,000 bonus for participating in exhibition games the prior year. In addition, he negotiated a performance bonus that would pay him for what he did best: hitting home runs. The performance bonus, a rarity for the Yankees, rewarded Ruth $50 for each home run he hit during the 1921 season. His 59 home runs were thus monetized into a $2,950 bonus. The total of his bonuses pushed his compensation for the season north of $30,000, more than tripling his $10,000 base salary.9

Paying Ruth a bonus to ensure his appearance in exhibition games seemed reasonable if projections about his popularity proved to be true. Just days after the purchase was announced, the New York Times reported that “the Yankees, with Babe Ruth as the headline attraction, are going to be billed through Florida like a circus.” According to the report, the Jacksonville Tourist and Convention Bureau planned to launch an extensive advertising campaign around the Yankees and Dodgers, both of whom trained locally. The festivities would continue as the teams made their way north for Opening Day. They planned a series of five exhibition games, with an additional three in Ebbets Field just prior to Opening Day.10 As long as Ruth was in the lineup, the crowd was certain to be at capacity.

The exhibition game bonus technically required Ruth to do extra work beyond that specified in his standard player contract. (Never mind that teams routinely exploited their players by squeezing in exhibition games to earn an extra gate while sharing none of it with the players.) Ruth was nobody’s fool. He could feign an injury, eat too many hot dogs, or “get lost” while driving to the ballpark easily enough to skip many of those games. The Yankees knew this, and paid him accordingly. But Ruth didn’t need a bonus to hit home runs. That came naturally.11 The bonus did seem to have its intended effect, what with Ruth breaking his already seemingly unbreakable record of 54 home runs from the previous year. It also resulted in the Yankees paying him $2,950 they would not otherwise have had to. Between his exhibition-game and-home run bonuses, Ruth earned more than the annual salaries paid to all but three of his teammates. His home-run bonus alone was higher than the total pay earned by four of them.12

Babe Ruth’s 1921 contract addendum with the New York Yankees

(Click image to enlarge)

BONUS CLAUSES

While bonus clauses are commonplace in twenty-first-century baseball contracts, such was not always the case. There are currently 3,491 contracts in my database for the years 1911 through 1921. Of those contracts, 363 (10.4 percent) contain bonus clauses.13 During that same time span the Yankees were more generous in this regard, including bonus clauses in 14.7 percent of their contracts (Table 1). For comparison, a sample of nearly 4,000 contracts dating from the 1990s into the early twentieth century showed 53 percent contained bonus clauses.14

Bonuses were rare going into the 1921 season. Performance bonuses that provided a realistic opportunity for the player to earn additional pay were even more rare. And performance bonuses offered by the Yankees were almost nonexistent. No player was granted a performance bonus by the Yankees until 1919. Throughout the rest of the league, 37 percent of all bonus clauses in major-league baseball contracts were performance-based during the decade ending in 1920.

The first Yankees to be offered a chance to increase their base pay as a direct result of their own performance were Frank “Home Run” Baker and Ernie Shore, in 1919 (Table 2), Baker’s contract included a clause that would award him an additional $200 on top of his $10,500 base salary if he played in 75 games. Baker earned the bonus, boosting his total compensation by 1.9 percent, when he appeared in 114 games for the Yankees that season. Shore was promised a $500 bonus if he won 15 games and the team finished either first or second. Neither he (five wins) nor the Yankees (third place) met the requisite condition for the bonus, so Shore had to settle for his $6,000 salary for the year. Shore had the same contract the following season, with the same result. Bob Meusel, on the other hand, earned his $300 bonus in 1920 by appearing in 119 games, far more than the 50 necessary to earn the bonus. Meusel’s bonus added nearly 10 percent to his $3,200 salary.

The Yankees added bonus clauses to seven contracts in 1921 (Table 3). Ruth was not the only Yankee to have a performance clause included in his contract that year, but he was the only one to earn it. Waite Hoyt was promised $1,000 if he could win 20 or more games and help the Yankees to a top-three finish in the league. The Yankees did win the pennant, but his win total fell one short of the required 20. Ruth, of course, cashed in big time with his bonus. It was the largest performance bonus the Yankees were to pay out during the remainder of his tenure with the club in both amount ($2,950) and percentage of base pay (29.5 percent). It was also larger than any performance bonus paid by any other team during this same time period.

Ruth’s performance bonus was in theory unlimited, since he was promised $50 for each home run. No other player was granted a performance bonus during the period 1911-34 that had an open-ended payout possibility. There were, however, performance bonuses that promised a payout that would have exceeded $2,950, though none of them were earned.

In 1920 the Cubs included a tiered performance-bonus clause in Lefty Tyler’s contract. Lefty was promised an escalating bonus that began at $1,000 for winning 10 games, climbing to $3,000 if he won 25, which would have been a hefty 75 percent increase of his $4,000 salary. Alas, poor Lefty won only 11 games that year. In 1928 James Cooney’s contract with the Boston Braves included a $4,000 bonus if he appeared in 100 games. He played in only 18 games before being shipped off to Buffalo on June 22.15 In 1930 the Senators offered a tiered bonus to Goose Goslin that would pay him $2,000 for hitting .320, and an additional $2,000 each for reaching .335 and .345. Goslin claimed the first level bonus by hitting .326.

Ruth’s outsized bonus earnings in 1921 had an impact on his future contracts, but did not significantly alter Yankees behavior regarding bonus clauses in general. After 1921, Ruth’s base salary exploded to $52,000, then $70,000 in 1927 before peaking at $80,000 in 1930-31. In return for higher base salaries, the Yankees eliminated bonus clauses from his contract until 1930. For the last five years of his career with the Yankees, Ruth’s salary was padded each year by 25 percent of the gate for any exhibition games in which he played, increasing his salary by about 5 percent each year.

WHY BONUS CLAUSES?

What is the purpose of adding a bonus clause to a player’s contract? In the modern era of competitive sports labor markets, the presence of a bonus condition in the player contract is simply part of the negotiation process. The greater the demand for a particular player, the greater his ability to negotiate bonus clauses. But why negotiate a bonus clause when you can simply opt for the guaranteed salary?

The salary is, of course, a payment for the performance of the player. But salaries are determined in advance of the actual performance, so that the team is not paying for what is actually being produced, but rather is buying an expected level of production predicted from past performance. Bonus clauses are one way of reducing the downside risk to the team that they will pay for under-performance. If an MVP performance is what the team expects to buy, then an MVP bonus clause will be paid only if the player wins the award. Of course, this means the risk of under-performance is now borne by the player. But the presence of the clause allows for the player to cash in on an unexpectedly great season.

A common argument for bonus clauses is that they provide players with the proper incentive to work hard. In the case of Babe Ruth’s 1921 contract, the exhibition-game clause certainly gave him the incentive to show up for those lucrative (for the Yankees) contests. Perhaps the home-run bonus provided him incentive to stay fit and keep his batting eye sharp, thus avoiding any potential letup in effort that might result in decreased production. (After all, with no home-run bonus in 1922, Ruth belted only 35, fourth in major-league baseball.)

There is a good reason to use bonuses in an effort to give players an incentive to give maximum effort. It is hard for a team to monitor and enforce effort. It is not always clear when a player is dogging it just a bit, actually fatigued during the dog days of August, or playing through a nagging injury. So how to entice a player to monitor himself and deliver his best effort at all times? Give him the incentive via a performance bonus. After all, who better to make sure he is giving his best effort than the player himself? It is more likely that a player will put forth that extra effort when he has money on the line.

CONCLUSION

While bonus payments were not common during the quarter-century of this study, when they were used, they could prove to be quite lucrative for the players involved. And as we have seen, if that player was Babe Ruth, they could be a bonanza. After a record-setting home-run barrage in 1921, perhaps aided by the financial incentive provided by the bonus, the Yankees chose to reward Ruth directly with a higher salary in future contracts instead of incentivizing him with a performance bonus. We will never know if they made the right decision. Perhaps if they had continued to include home-run bonuses in his contracts it wouldn’t have taken him six years to break the single-season home-run record for the fourth and final time. Is it possible the Yankees lost a few dozen Ruthian clouts for the want of a few thousand dollars? The world will never know.

MICHAEL HAUPERT is Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. He is co-chair of the SABR Business of Baseball Committee, editor of the newsletter “Outside the Lines,” and a 2020 recipient of the Henry Chadwick Award.

Table 1: Bonus clauses 1911-1934

|

Year |

Total MLB |

New York Yankees |

||||||

|

Contracts |

Bonus Clauses |

% Bonus |

Performance Bonus |

Contracts |

Bonus Clauses |

% Bonus |

Performance Bonus |

|

|

1911 |

27 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1912 |

307 |

7 |

2.3% |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1913 |

389 |

12 |

3.1% |

3 |

10 |

1 |

10% |

0 |

|

1914 |

239 |

24 |

8.3% |

6 |

14 |

3 |

21.4% |

0 |

|

1915 |

391 |

49 |

12.5% |

17 |

36 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1916 |

401 |

40 |

10.0% |

15 |

36 |

2 |

5.6% |

0 |

|

1917 |

373 |

55 |

14.7% |

24 |

37 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1918 |

166 |

16 |

9.6% |

6 |

34 |

7 |

20.6% |

0 |

|

1919 |

385 |

35 |

9.1% |

15 |

27 |

7 |

25.9% |

2 |

|

1920 |

409 |

59 |

14.4% |

21 |

24 |

9 |

37.5% |

2 |

|

1921 |

404 |

66 |

16.3% |

16 |

27 |

7 |

25.9% |

2 |

|

1922 |

419 |

72 |

17.18% |

16 |

39 |

4 |

10.26% |

1 |

|

1923 |

435 |

63 |

14.48% |

17 |

39 |

5 |

12.82% |

0 |

|

1924 |

442 |

41 |

9.28% |

6 |

49 |

1 |

2.04% |

0 |

|

1925 |

449 |

59 |

13.14% |

3 |

53 |

5 |

9.43% |

2 |

|

1926 |

447 |

39 |

8.72% |

5 |

44 |

2 |

4.55% |

1 |

|

1927 |

451 |

66 |

14.63% |

8 |

44 |

13 |

29.55% |

3 |

|

1928 |

447 |

59 |

13.20% |

14 |

45 |

3 |

6.67% |

2 |

|

1929 |

455 |

67 |

14.73% |

11 |

39 |

9 |

23.08% |

3 |

|

1930 |

430 |

61 |

14.19% |

11 |

50 |

14 |

28.00% |

4 |

|

1931 |

420 |

47 |

11.19% |

20 |

39 |

13 |

33.33% |

0 |

|

1932 |

426 |

27 |

6.34% |

2 |

37 |

16 |

43.24% |

0 |

|

1933 |

362 |

24 |

6.63% |

2 |

34 |

10 |

29.41% |

0 |

|

1934 |

396 |

37 |

9.34% |

4 |

35 |

9 |

25.71% |

0 |

Source: Haupert Baseball Salary Database

Table 2: Performance bonus details in Yankee contracts, 1919-30

|

Year |

Bonus Contracts |

Performance Bonus |

Details of Performance Bonus Clauses |

|

1919 |

7 |

2 |

*Frank Baker $200 for 75 full games played Ernie Shore $500 for 15 wins and team finish 1st or 2nd |

|

1920 |

9 |

2 |

*Bob Meusel $300 for appearing in 50 games Ernie Shore $500 for 15 wins and team finish 1st or 2nd |

|

1921 |

7 |

2 |

Waite Hoyt $1,000 for 20 wins and team finish 3rd or better *Babe Ruth $50 per home run |

|

1922 |

4 |

1 |

*Bob Shawkey $500 for 18 wins |

|

1923 |

5 |

0 |

|

|

1924 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

1925 |

4 |

2 |

Bob Shawkey $500 for 20 wins Walter Beall $1,000 for 18 wins |

|

1926 |

2 |

1 |

*Herb Pennock $500 for 20 wins |

|

1927 |

12 |

3 |

*Waite Hoyt $1,000 for 20 wins Herb Pennock $1,000 for 25 wins Walter Ruether $1,000 for 15 wins |

|

1928 |

3 |

2 |

*Waite Hoyt $1,000 for 22 wins Herb Pennock $1,000 for 25 wins |

|

1929 |

9 |

3 |

Waite Hoyt $1,000 for 22 wins Herb Pennock $1,000 for 25 wins Benny Bengough $1,000 for catching 75 games |

|

1930 |

13 |

4 |

*Benny Bengough $1,000 per 25 games caught up to 75 Owen Carroll $1,000 for 15 wins plus additional $1,000 for 20 wins Waite Hoyt $200 per win above 15 Herb Pennock $500 per win above 15 |

Notes: *bonus earned; in 1930 Bengough earned $1,000 for his performance bonus. The Yankees did not include any performance bonus clauses in contracts from 1911-18 or 1931-34.

Source: Haupert Baseball Salary Database

Table 3: Details of Yankee bonuses in 1921

|

Player |

Amount |

Earned |

Condition |

|

Mike Gazella |

$500 |

$500 |

College expenses |

|

Waite Hoyt |

$1,000 |

$0 |

Wins 20 games and team finishes 1st, 2nd or 3rd |

|

Bob Meusel |

$1,000 |

$1,000 |

If player is “good” and team is 1st, 2nd or 3rd |

|

Roger Peckinpaugh |

$500 |

$500 |

Team finishes 1st, 2nd or 3rd |

|

Jack Quinn |

$500 |

$500 |

Team finishes 1st, 2nd or 3rd |

|

Babe Ruth |

$20,000+ |

$22,950 |

Signing bonus; exhibition game bonus; $50 per home run |

|

Wally Schang |

$3,500 |

$3,500 |

Signing bonus |

Sources

American League Base Ball Club of New York Records 1913-1950, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Baseball-reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/.

Cot’s Baseball Contracts, https://legacy.baseballprospectus.com/compensation/cots/.

Haupert Baseball Salary Database, private collection, 2021.

Haupert, Michael, “Finessing the Standard Player Contract,” Outside the Lines, Summer 2007, 1, 7-13.

Haupert, Michael, “The Business of Being the Babe,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 50, No. 1 (Spring 2021), 7-15.

Haupert, Michael, “The Sultan of Swag: Babe Ruth as a Financial Investment,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Fall 2015), 100-07.

Haupert, Michael, “Sale of the Century: The Yankees Bought Babe Ruth for Nothing,” in Bill Nowlin, ed., The Babe (Phoenix: SABR, 2019), 79-82.

Leavy, Jane, The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created (New York: Doubleday and Co., 2018).

Notes

1 “The High Cost of Home Runs,” New York Times, January 7, 1920: 18.

2 For a discussion of Ruth’s financial and marketing impact, see Leavy, Chapter 9. For details on the financial impact of Ruth on the Yankees, see Haupert 2015, 2019.

3 Williamson hit 27 home runs in 1884 for the Chicago White Stockings.

4 The Phillies hit 64 home runs, and Ruth’s own Yankee teammates, who belted 61 homers, also bested the Babe.

5 Attendance in 1920 exceeded the previous three seasons combined. It would be a quarter-century before the Yankees would top that mark.

6 Haupert Baseball Salary Database.

7 Cot’s Baseball Contracts.

8 Haupert 2019.

9 With his share of the World Series proceeds, his net pay from the Yankees that year was $31,290. Ruth was notorious for racking up fines and borrowing money from the Yankees against his future salary. This salary figure reflects the net amount transferred to Ruth by the Yankees in 1921. American League Base Ball Club of New York Records 1913-1950, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

10 “To Boost Yanks’ Visit Jacksonville Will Advertise Spring Trip Like Circus,” New York Times, January 9, 1920: 18.

11 During his career with the Yankees, Ruth averaged one home run every 3.2 games.

12 On the low end were Thomas Connelly, Al DeVormer, Nelson Hawks, and Tom Rogers, who appeared in a combined 73 games. After Ruth, the three highest-paid Yankees were Home Run Baker ($13,000), Carl Mays ($12,000), and Bob Shawkey ($8,000).

13 There are several types of bonus clauses in standard player contracts of this period. These clauses are categorized by type as follows: team attendance, team finish in standings, signing, player performance, roster, team profit, good effort, penalty, nonpecuniary, and clause deletion. For a further discussion of bonus clauses in baseball contracts see Haupert 2007.

14 Haupert Baseball Salary Database.

15 Baseball-reference.com.