Early Baltimore Ballparks

This article appears in SABR’s Baltimore Baseball (2021), edited by Bill Nowlin.

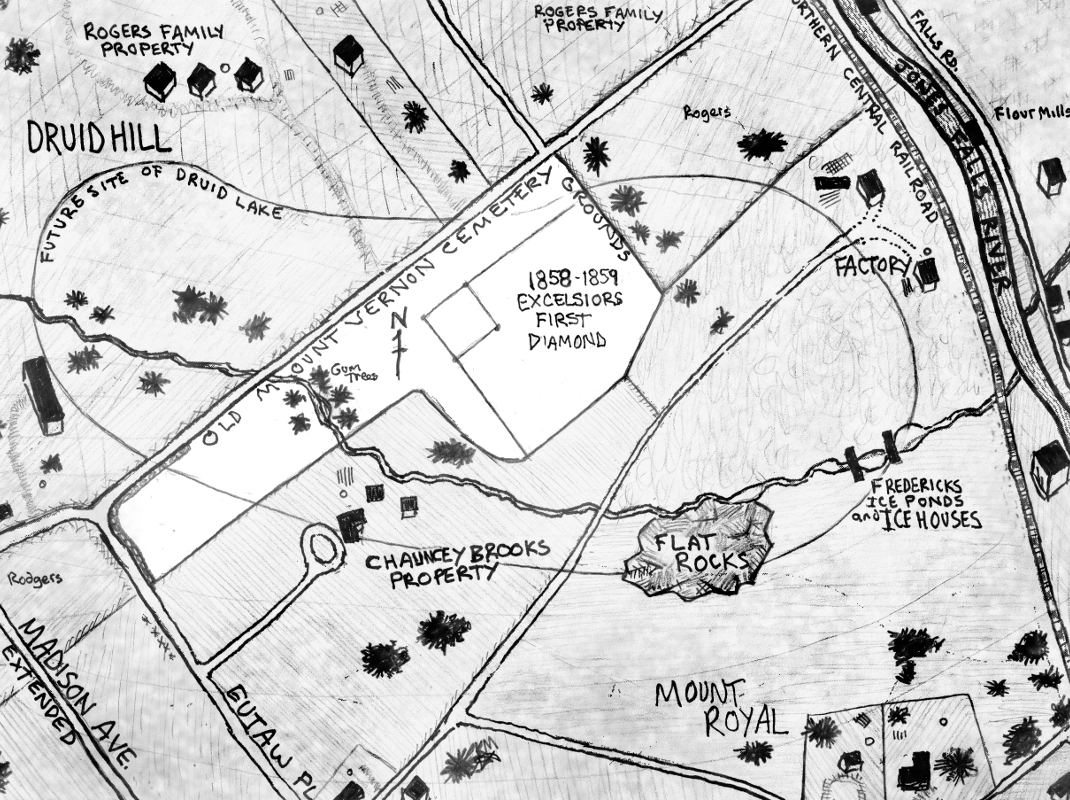

1. Flat Rock (a/k/a Druid Hill Park) 1858-1859

When Baltimore grocer, George F. Beam, formed the Excelsior Base Ball Club in the summer of 1858, the choice for a practice space was imperative since ball playing within city borders was often impractical, and at times illegal. Just south of the Rogers family’s Druid Hill plantation, there was an area originally called Flat Rock, named so for a large crop of stones near the road to the mansion. It’s hard to imagine, but until 1888, Baltimore ended at North Avenue, and anything beyond was rolling farmland.

Beam and teammates chose the treeless and loosely graded site of the old Mount Vernon Cemetery, as it was the flattest, clearest land for play. The cemetery was dedicated in 1852, but the space quickly filled to capacity and became overgrown with neglect. Nicholas Rogers, whose land the graveyard bordered, sued the owner to have the corpses removed and reinterred in Greenmount Cemetery to increase the value of his property, and the parcel went essentially unclaimed in 1858. It was an ideal location, with privacy and no neighbors to complain, but best of all, it was free.

It took some work, but once the men cut the weeds back and cleared out the debris, they laid out the very first baseball diamond in the State of Maryland. Home plate was surveyed with the batter facing east, and the pitcher facing the often-intrusive sun. Obviously, no local competitors existed at first, so they practiced and played inter-squad games on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, though within a year, they would be joined by other clubs.

Close to Flat Rock was a saloon owned by Jacob Hartzell, called the Park House, which became a convenient meeting spot for refreshments before and after practice. In years to come, teams would build small clubhouses out back to change clothes and store equipment. The diamond on the old cemetery was only used by the Excelsiors for a few months in 1858 and the beginning of 1859 when it was announced that the City had completed the purchase of the Rogers’ family lands to establish Druid Hill Park; the third municipal park in the country at the time. By 1870, the entire southeastern corner of the park was dug out, and a large retaining wall built up into the country’s largest earthwork dam at 119 feet high. Once the reservoir was flooded, all trace of the first baseball field in Maryland history vanished and has been under a permanent rain out ever since.

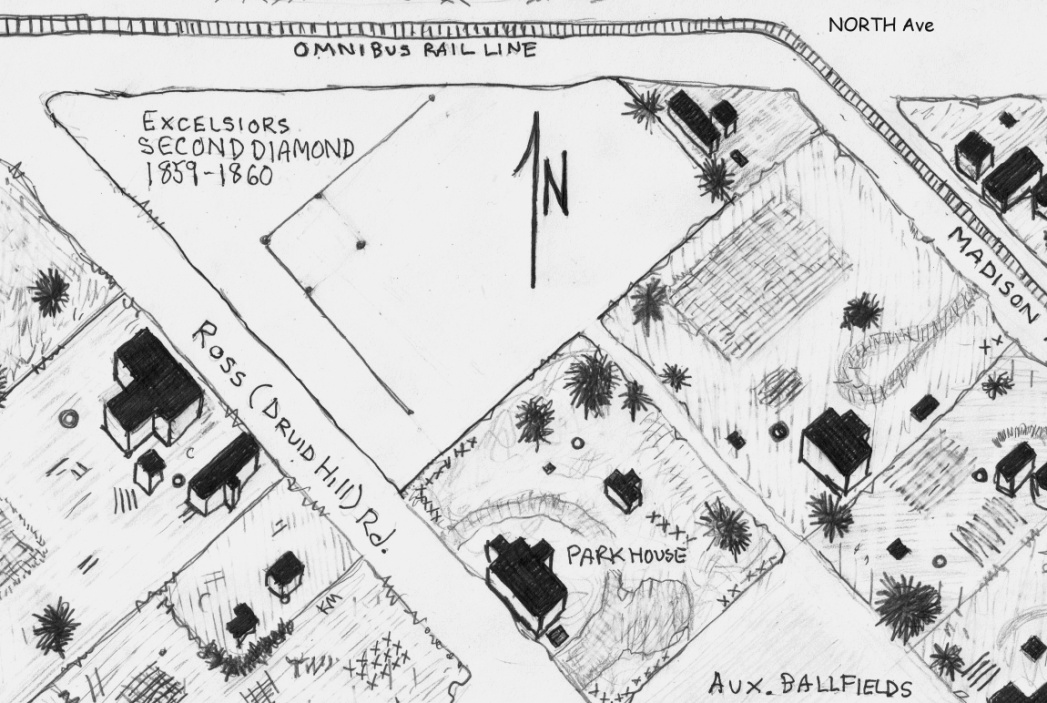

2. Excelsior Field 1859-1860

In 1859 the Excelsiors rented a piece of land on the border of the city at the corner of Madison Avenue and North Avenue, with Gold Street on the south edge. Baltimore’s public transit system was small and privately operated, but one route ran up Madison Avenue close to the ball fields, ending at the city boundary. This accessibility helped stimulate interest and the Continental, Druid, Oriental, and Peabody base ball clubs all came together over the next year, representing every corner of the city. The Baltimore Base Ball Club, a short-lived squad, made its mark on history on August 23, 1860, when they took on the Maryland Base Ball Club.

“BASE BALL- The first match game of base ball between rival clubs which has ever taken place in this city came off on the afternoon of the 23rd between the Baltimore and Maryland clubs. The game played on the grounds of the Excelsior club and was witnessed by about two hundred persons, a large portion of whom were ladies. The Maryland club have been playing but a very short time and the Baltimore for the last four months. The game was very well played, considering the disparity of ages between the members of the two clubs – the oldest members of the Baltimore club being but fifteen years of age, while those of the Maryland are all grown men. The playing of Master H. Vaughn of the Baltimore as catcher was very fine having caught four or five on the fly and as many on the bound. The batting of the Baltimore was better than the Maryland with but one exception, that done by Robert Green. The game was won by the Baltimore club with the following score: Baltimore 29, Maryland 11.”1

The Brooklyn Excelsiors came to town on September 22, 1860, to play at the Baltimore Excelsiors diamond on North Avenue. During the pre-game warmup the Baltimore American observed of the Brooklynites that, “the ball passed from one to the other with great precision, and seldom was it allowed to slip through the fingers of any of them. This little exhibition made it manifest that the Baltimore Club would learn a few new points before the game closed.”

The visitors took the field first, and crafty pitcher Jim Creighton retired the side in order, taking down George Beam on three pitches. Beam then took to the box and promptly gave up a bruising 16 runs in the first four innings. Brooklyn continued to pile it on while Creighton shut down Baltimore inning after inning, until he let a pitch slip and hit a batter in the head with a high fastball.

Creighton was moved to the outfield, where in the late innings of the one-sided slaughter, he started what was likely the first triple play to occur in the State of Maryland. Baltimore had Samuel Patchen on second and John K. Sears on third with none out. Hervey Shriver got a hold of a good one and sent it soaring into the sky. The long fly ball drifted back on Creighton, who made a spectacular catch on the run for the first out.

Without a pause, Creighton’s cannon arm threw the ball in to third baseman, John Whiting, who tagged Sears for the second out. Whiting then relayed quickly to Asa Brainard waiting at second, just in time to nab Patchen for the third and final out. Deflated by their base running gaffe and inability to defend against their opponent’s superior hitting, the home team was overwhelmed by a football-like score of 51-6.

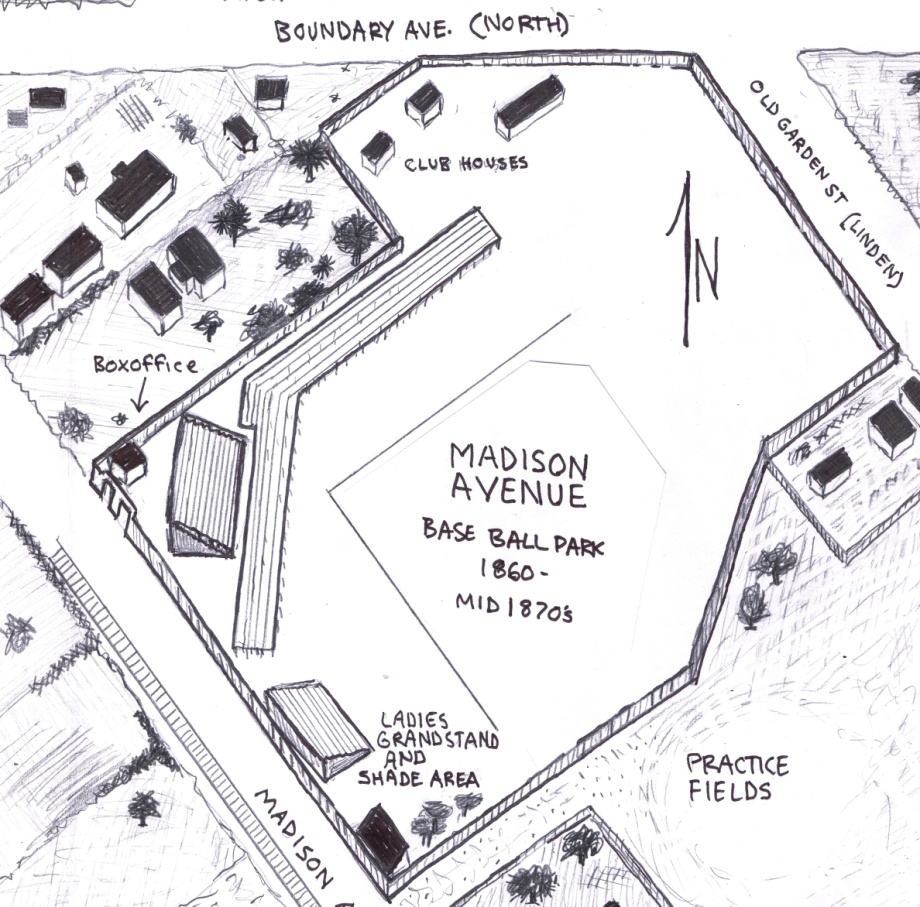

3. Madison Avenue Base Ball Grounds, 1860 to mid-1870s

Early in 1860, William Clapham Pennington, a lawyer and future president of the Baltimore Fire Insurance Company, helped form the Waverly Base Ball Club. The Penningtons owned several plots near Flat Rock and took the initiative in establishing the Madison Avenue Grounds, the first formal baseball park in Maryland. With many players leaving to fight in the war, the Waverlys merged with the Excelsiors in 1861 to form the Pastimes.

The venue itself evolved over a number of years, each season bringing improvements and expansion: benches and grandstands, fences to enclose the area for privacy, and a section for women who wished not to mix with the foul-mouthed men. Most games cost 10 cents admission, and special events, such as out-of-town teams, cost as high as a quarter. The diamond was also rented out to other teams for practice and several clubhouses were built in the outfield to accommodate. In winter, the outfield was flooded, left to freeze, and turned into a skating rink.

The location of the Madison Avenue Ball Grounds was just south of the corner of Madison Avenue and North Avenue. Eutaw Place, and Morris Street now cut through what had been the spacious outfield.

On August 27, 1867, the New York Mutuals, one of the best clubs in the country at the time, took on the Pastimes at Madison Avenue. When it came time to play the Pastimes, though, the Mutuals made a grave error and sent their “B” squad to Baltimore, thinking (correctly) that their amateur foes were pushovers. Madison Avenue was filled to capacity, but little was expected of the Pastimes, and the home crowd was shocked when Dick Thorn of the Mutuals gave up 14 runs in the first two innings.

The New Yorkers switched positions several times with no improvement. In the ninth the Pastimes tacked on seven runs, including a three-run homer by Louis Mallinckrodt! When the dust settled, the lowly Pastimes of Baltimore had slain the mighty New York beast with a nice cushion, 47-31.

“In proportion to the elation and congratulation indulged among the Pastimes and their friends is the depression and mortification of the vanquished champions. Particularly was the victory of the Pastimes a source of jubilation from the fact that the Baltimore boys had not only to contend with the reputed best nine in the country, but also with a partial and biased umpire. Mr. Glover’s decisions were frequently so reprehensible, so flagrantly partial and unjust, as not only to provoke the murmurs of the Pastimes, but to call forth the criticism of the fair-minded members of the Mutuals, in whose favor he constantly awarded… Whatever may be said by the interested, prejudiced or biased, it must be admitted that the playing of the Pastimes was up to the best and highest standard exhibited anywhere in the country. Where all played so well it would be invidious to commend individual action.”2

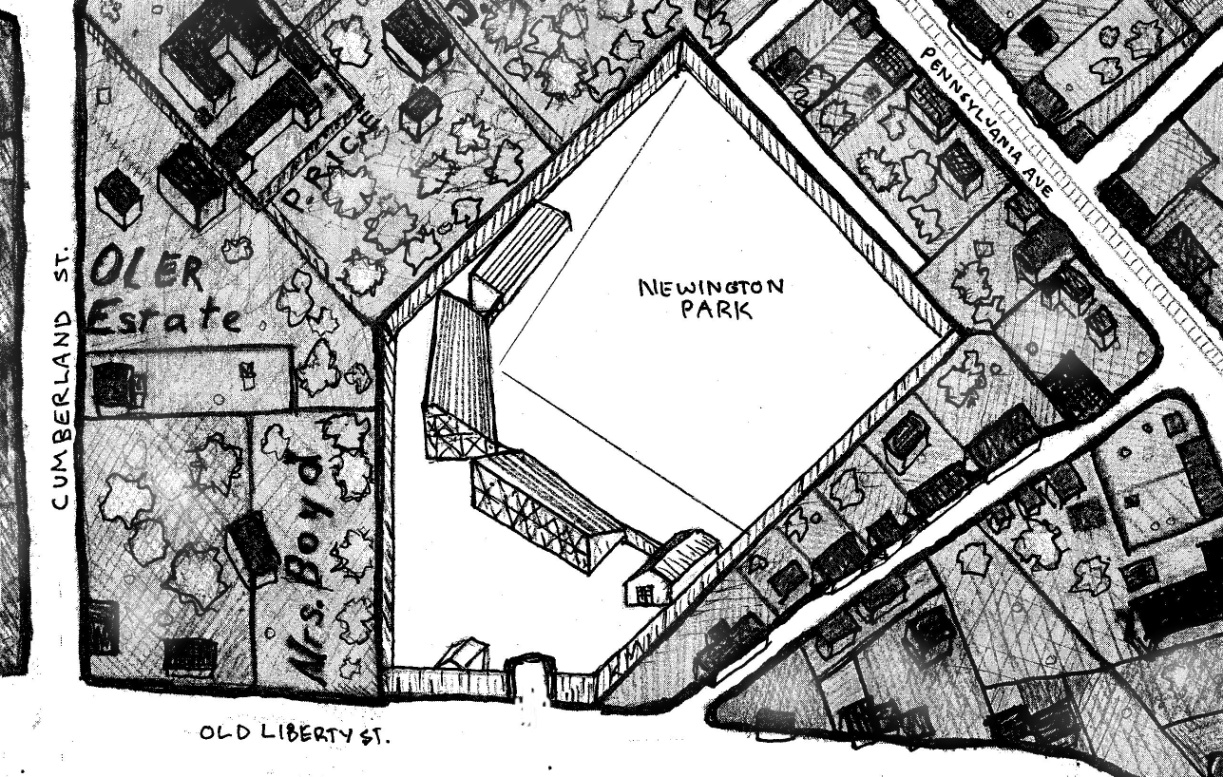

4. Newington Base Ball Grounds (a/k/a Newington Park), 1871 to mid-1880s

In early November 1871, the Lord Baltimore Base Ball Club elected officers and began negotiating a 10-year ground rent on a plot of land off Pennsylvania Avenue at Gold Street for a new ballpark. By the end of the month, three covered grandstands had been built to seat 2,000, and an additional two-tiered stand was planned especially for stockholders. The final sale was delayed until just after the New Year, and by then primary investor Michael Hooper Sr. had withdrawn from the endeavor, leaving Alphonsus Houck and his brother George to purchase the property rights on their own.

Samuel Snowden, chief litigator for the Newington Land and Loan Company, one of the largest public investment firms in the city facilitated the sale. In a very early example of corporate naming rights, the Pennsylvania Avenue Base Ball Park, was changed to the Newington Base Ball Grounds, to seal the deal.

The Lord Baltimores National Association home opener at Newington on April 22, 1872, was a huge success. Bobby Mathews and the Lord Baltimores trounced the New York Mutuals, 14-8, in front of 2,500 screaming fans, and an estimated 1,500 more outside, standing on sheds and rooftops and the surrounding trees infested with children. It may not sound like a big crowd, but Baltimore’s population was less than 40% of what it is now.

Seizing upon local history, the Lord Baltimores sported specially-tailored white silk shirts emblazoned with the Calvert family arms, yellow and black argyle socks, and mustard gray knickers topped off with a white cap. It may sound acceptable on paper, but when the public saw them for the first time, they laughed. Nicknames were plentiful. Yellow Legs, Mustard Trousers, Dandelions, and Canaries. Not very flattering. The silk shirts were flimsy, and the men felt unprotected. Unfortunately, the Lord Baltimores collapsed after the 1874 season and Newington featured mostly amateur clubs for the remainder of the decade.

On Tuesday May 9, 1882, the American Association Baltimore Base Ball Club moved into Newington Park for their home opener. The Baltimores lost to the Athletics, 4-2, and would go on to compile a season so historically bad the franchise was taken away from owner/manager Henry Myers and given to Billy Barnie and Alphonsus Houck for a new club; the Baltimore Orioles.

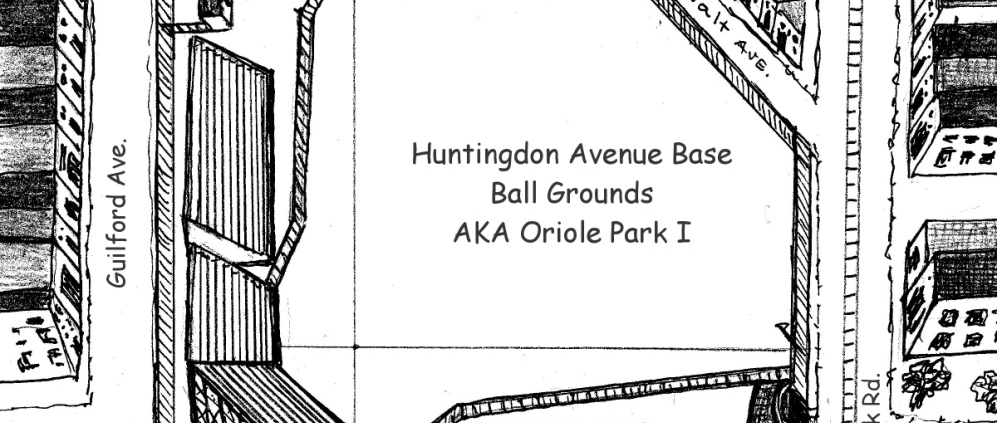

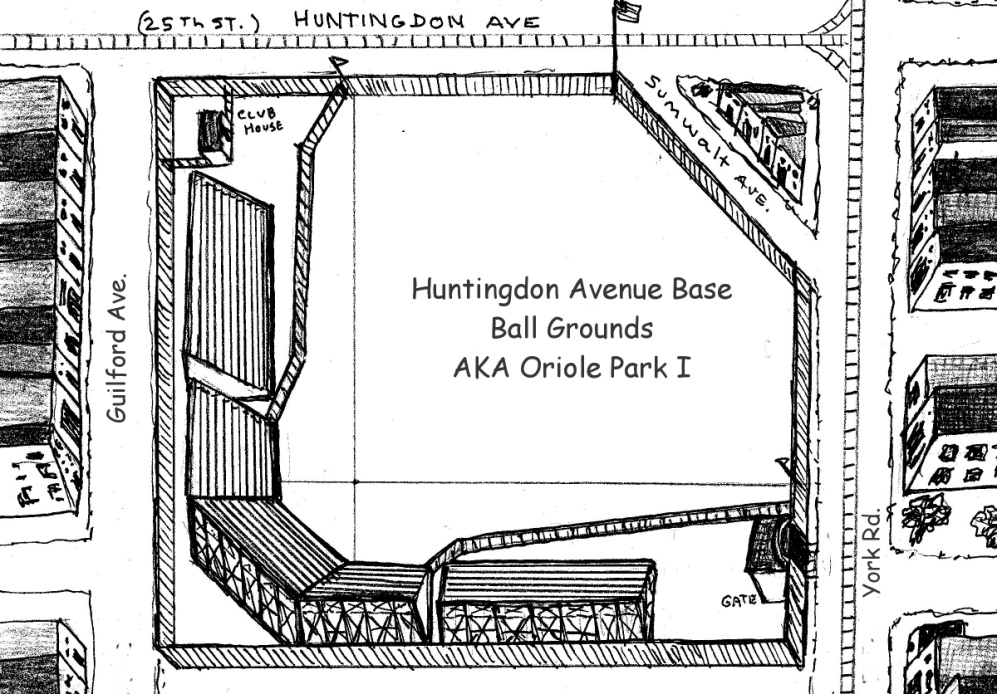

5. Huntingdon Avenue Base Ball Grounds (a/k/a Oriole Park I), 1883-1888

The search for a first nest led the Baltimore Orioles to an empty lot on the east side of Greenmount Avenue, south of Huntingdon Avenue, now known as 25th Street. Owned by the Sadtler family trust, the parcel was a wide-open field on the outskirts of town that had been used for over a decade by amateur clubs for practice.

Unlike its predecessors, the ballpark was in a central location and readily accessible by public transportation. As soon as the ink was dry on the lease, construction began on the Huntingdon Avenue Grounds. Nestled in a residential area, the park used the space efficiently. Though smaller in acreage than previous ballparks in the city, the Orioles built upwards instead of spreading out. A central amphitheater style grandstand that sat 1,200 was raised above the field level with the bottom portion serving as the backstop.

Along the right and left foul lines were two long sets of bleachers that held over 2,000 each, with space in the deep outfield for standing room only. A 10-foot-high wooden fence enclosed the entire perimeter to discourage onlookers. By comparison to Madison Avenue and Newington, the soon-to-be-nicknamed “Oriole Park” on Huntingdon Avenue was state-of-the-art.

On June 16, 1887, a rowdy crowd showed up at Oriole Park, eager to see the Birds best St. Louis and flirt with first place. Curt Welch of the Browns was one of the roughest and rudest of his era; often described as an illiterate and vulgar umpire baiter. Oriole fans had their eyes on him.

The Birds and Browns were tied at eight in the ninth. After scratching out a single, Welch tried to steal second. When he realized he was going to be thrown out by Chris Fulmer, Welch slammed into second baseman Bill Greenwood, who dropped the ball just after impact. Umpire John McQuade called Welch out — but not loud enough or gesturing clearly enough for anyone to get the call.

Greenwood had held on long enough to make the play, but no one was looking at McQuade — and Welch didn’t immediately walk back to the Browns bench. Everyone thought Welch was called safe. When Bill Barnie burst from the Orioles bench to demand judgment, Birdland turned into bedlam. The stands emptied. Men swarmed past the barbed wire lined picket fences and on to the field — straight toward Welch’s throat!

Angry fans surrounded the Browns, pushing and shoving several to the ground. Barnie and Charlie Comiskey agreed to call the game a tie, in hopes it would disperse the furious fans. It didn’t work. The police lost control of the situation. Browns ace and local boy Dave Foutz tried his best to calm the crowd, but when the throngs seemed uncontrollable, several Orioles smuggled Welch out of the park and off to Camden Yards Railway Station to catch the first train out of town. However, when they got to the ticket office, there was already a small mob anticipating Welch’s stealthy departure.

With no escape, Welch hid in his hotel, waiting out the night with a growing crowd of irate Baltimoreans gathering outside his window. A court hearing was held in the morning in which a contingent of local fans banded together to bring assault charges against Welch. Greenwood was called in to testify, but pleaded Welch’s innocence instead; stating that the play was nothing out of the ordinary. Welch was released on a $200 ($5K) bond, paid in full by Orioles co-owner (with Barnie), Harry Von Der Horst, and wisely benched for the final game of the series. The Sporting News wrote, “The Baltimore audience displayed very little of the instincts of human beings, but on the contrary conducted themselves like idiots.”

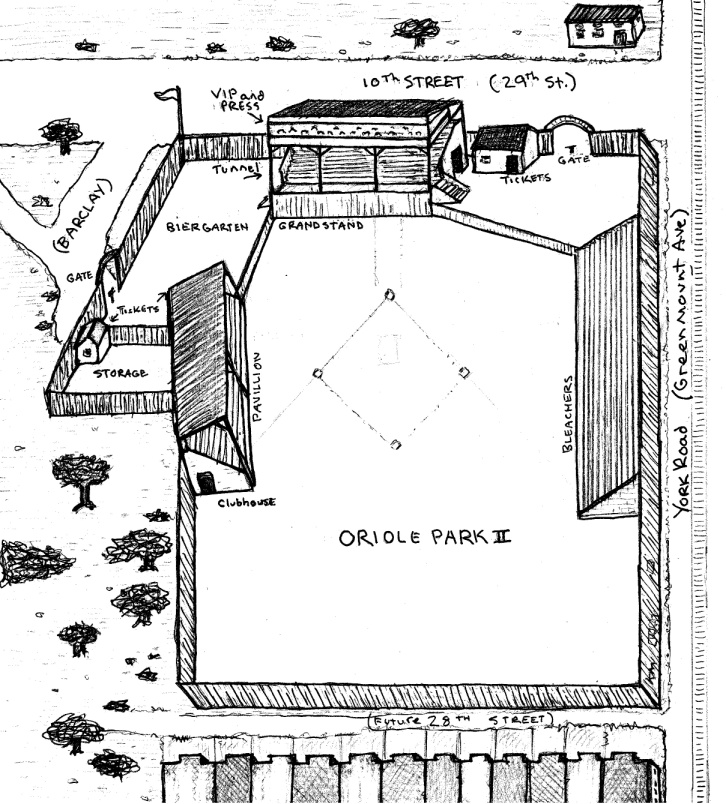

6. Oriole Park (a/k/a Oriole Park II), 1889-1891

At the corner of York Road and Tenth Street, (now 29th Street and Greenmount Avenue), Bill Barnie and Harry Von Der Horst built the second Oriole Park, though it is the first to have that name exclusively for its tenure. The main grandstand, elevated to form the backstop, could seat 2,000, and there was a second tier with private boxes for press and VIPs. Bleachers on the first-base side sat 3,500, and a covered pavilion along third for another 1,500. A passageway under the grandstand would join the two halves, with generous standing room for the biergarten between.

The team clubhouse was tucked underneath the southern end of the covered pavilion. One drawback to the new location on 29th Street was that only the York Road streetcar line ran up that far. Patrons coming from the west now had the option of transferring streetcars or walking 15 minutes north.

General admission at the new park was held at 25 cents, but once inside a separate admission of another quarter would get you a grandstand seat, or 15 cents for the pavilion. The location was inconvenient and within a year the club would be forced to look for another location due to dwindling attendance. When construction on Union Park (Oriole Park III) lagged, Oriole Park (II) was used for the first home series of the 1891 season.

The 1889 Louisville Colonels were having the worst possible season imaginable. A streak of 18 straight losses brought them to Baltimore on Wednesday June 13, and their luck did not change. After losing to the Orioles, Colonels owner-manager Mordecai Davidson laid down a fine of $25 ($650) for each player if they lost again. The men brought up the issue of owed back pay and refused to take the field for the next game.

A war of words escalated, and Davidson made legal threats. A cancellation was hastily issued, and a doubleheader added to make up for it. As the minutes ticked away towards the next game, Davidson waited at Oriole Park for his men to show up. Only six Louisville players did. The umpire was ready to call a forfeit, but in a moment of ingenuity, Davidson hired three replacements right out of the grandstand to fill out the roster for the day. Local boys Charles Fisher, John Traffley, and Mike Gaule were suddenly in the majors! Their stay would be short, barely a sip of coffee, as a rainstorm cut their debut at five innings and Louisville losing their 20th straight, 4-2.

Following the game, striking Colonels Guy Hecker‚ Pete Browning, and Harry Raymond, consulted with Bill Barnie, who convinced them to return to their club and assured them their grievances would be brought before the American Association. Before the first game of the Saturday doubleheader, Barnie made a roster move. To give the Colonels an even chance, he added local pitcher George Goetz to the Orioles roster to make his one and only professional start. And Goetz pitched a pretty darn good game for a first-timer, giving up just three earned runs through the first seven innings before allowing another in the eighth.

Colonels pitcher Todd “Toad” Ramsey, a once dominant workhorse, had a sore arm and Baltimore came back to tie in the ninth and thus force extra innings. The Orioles then knocked in four runs in the top of the 10th to win the game, 10-6. The night cap didn’t go well for the Colonels either and were able to scratch out only one base hit against an ice-cold Frank Foreman. Louisville committed seven errors and Baltimore rolled to an easy 10-0 shutout. The Colonels losing streak would finally stop at 25 games.

All map images © Ken Mars 2016

Sources

Research for this article is based on the author’s book, Baltimore Baseball First Pitch to First Pennant 1858-1894, Old Frog Publishing, 2018.

Notes

1 Baltimore Daily Exchange, August 29, 1860.

2 Sunday Telegram, September 1, 1867.