Early Black Baseball in Baltimore: 1865-1887

This article appears in SABR’s Baltimore Baseball (2021), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Baseball came to Baltimore in 1858 and grew in popularity over the next few years to become a genuine sensation. By the end of the Civil War, Baltimore had over 25,000 free African American residents, and therefore logical to believe that there were baseball games being played within their community. The game was too popular and evidence of black baseball clubs in other cities at the same time is well known. As the game grew during the post-war boom, Baltimore newspapers were slow to report on the progress of African American clubs, and the first reference to a game played by a black baseball club comes from the Evening Star in Washington D.C., not a hometown source where the actual game took place.

On August 16, 1870, the Enterprise Base Ball Club played the Washington Mutuals at the Madison Avenue Base Ball Grounds, the premiere ballpark in Baltimore at the time. The Washingtonians out slugged their hosts by a good margin, 51-26. Charles Douglass, the son of Frederick Douglass, was the captain and star player for the Mutuals, one of the best black clubs in the Mid-Atlantic at the time. But, before a baseball club can start playing games, they have to have a place to practice, and back then Baltimore had very strict laws as to where and when such pastimes could occur. There are numerous accounts of ball players being arrested and fined for playing on the Sabbath, or on public property. The need for a wide-open space away from anyone who might complain about noise or broken windows, was crucial to even think about getting started.

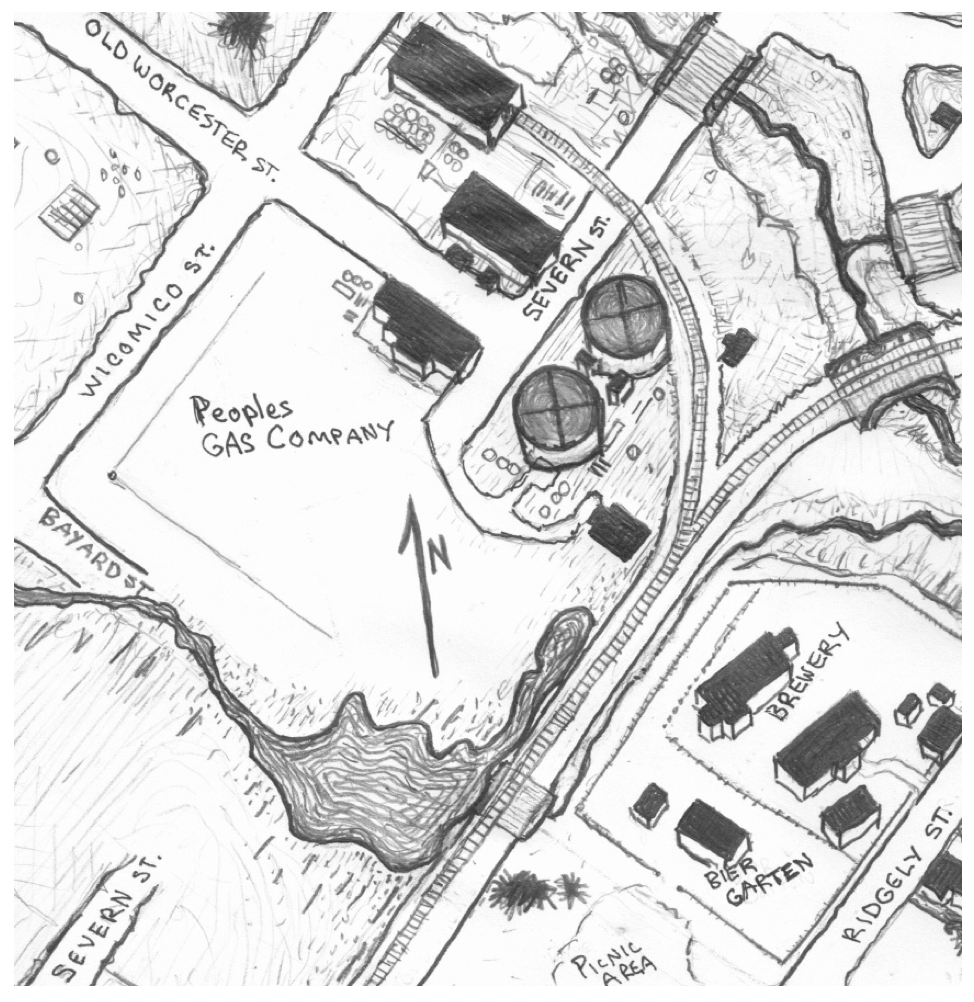

In the late 1860s, African American players established baseball diamonds in South Baltimore. The neighborhood had brick yards, factories, flat open fields, and very few residents. Land along the railway line in particular was open and undesirable because of the noise. There were two diamonds of note in this area: Stowman’s Park, used primarily by white clubs and another on the opposite side of the B & O railway line, used by black clubs. In between was the Bauernschmidt Brewery, a liberal supplier of libations to any who could pay. After hours or on the weekends, the neighborhood was mostly vacant of anyone who might complain about crowds or a rowdy game.

As more businesses moved into South Baltimore, a large natural gas plant was built to meet the demand. The monstrous People’s Gas Company became the main supplier for the area and the parcel adjacent to the plant remained empty for decades. For perspective: this location was less than a half mile from where the Baltimore Black Sox Maryland Park and Westport Park were, and about two miles from the Elite Giants Westport Stadium.

Throughout the mid 1870s the Lord Hannibal Base Ball Club grew to become the city’s premiere black team, playing regularly at Newington Park, the successor to Madison Avenue. Newington was built in 1871 for the short-lived Lord Baltimores of the National Association. The Great Baltimore Fire of 1873 plunged the city into a depression and the club was gone soon after. However, in the absence of a major-league team, amateur and semipro baseball flourished.

The Lord Hannibals were part of a surge of local black teams in the late 1870s and early 1880s, along with the Quicksteps, Mutuals, Atlantics, and Mansfields. The Baltimore Sun reported in July 1883 that Baltimore had intended to form a league with other black clubs from Philadelphia, Washington, Richmond, and Norfolk for 1884. This did not come to pass as a formal arrangement, but as inter-city games increased over the next few years, it was a matter of time, trial, and error before professionalism would take hold.

Circa 1884, professional baseball was still integrated, though on a very small scale. Catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker of the American Association Toledo Blue Stockings played in Baltimore twice in 1884. On June 4, the Orioles blanked Toledo, 8-0, at Oriole Park on 25th Street. Walker recorded 10 putouts and three errors while going hitless at the plate. And, on June 6, the Birds lost, 4-2. Oriole pitcher and future umpire Bob Emslie only gave up one earned run, with the other three scoring on errors. Walker again went hitless at the plate but caught Tony Mullane’s pitching with ease.

By 1886, integrated baseball clubs were growing scarce and skilled African American ballplayers went unsigned. In 1887, only five teams in the International League were integrated. It was a difficult time of backwards thinking and divisive arguments. With too much talent and desire to sit on the bench, the 1887 National Colored Base Ball League fought to establish itself in the wake of this social turmoil. But outside factors would conspire to make their inaugural season short.

After the Civil War, railway construction kicked into high gear. Small towns cropped up along every new line. Some thrived, but many failed. In a little over a decade, the boom went bust, and a national depression throughout the late 1870s was largely blamed on bad railroad investments. The railroads formed territorial monopolies and made their own rules, charging farmers in the west far more to ship east than their counterparts to ship west.

Under pressure from citizens sympathetic to the farmers, in 1887, President Grover Cleveland signed the Interstate Commerce Act, which aimed to ensure fair rates and regulations. The railroad magnates, who had greased pockets in Washington for decades to get their way, were not pleased to be put under supervision and plotted revenge. Imagine for a moment planning a trip, months in advance and laying out a careful budget that normally would have been plenty — only to see your travel expenses double without warning. This is exactly what lay ahead for baseball clubs in the summer of 1887, when all group rates were repealed, and general fares went up.

A series of meetings throughout late 1886 culminated in February 1887, when representatives from the Philadelphia Pythians, Pittsburgh Keystones, New York Gorhams, Louisville Falls Citys, Boston Resolutes, and Lord Baltimores came together to finalize the schedule for the National Colored Base Ball League, the first professional baseball league owned, operated, and staffed by African Americans.

Future Hall of Famer and author Sol White played second base for the Pittsburgh Keystones. Welday Walker, little brother of Moses Fleetwood, also played for Pittsburgh as catcher and outfielder. Arthur Thomas played third base for the Lord Baltimores and went on to have a great career with the Cuban Giants. Another future Hall of Famer, Bud Fowler, would have played for the Cincinnati Browns, but they lacked funding and didn’t enter the league in time. But possibly the most interesting player was James W. Wilson, left fielder for the Lord Baltimores. Wilson was born in Liberia and came to the States to study at Lincoln University. He is the first confirmed professional baseball player from the continent of Africa.

The Lord Baltimore Base Ball Club could possibly be an evolution of the Lord Hannibals, taking the name of the old National Association club as their own. They lucked out and secured use of Oriole Park on 25th Street for over a month while the Orioles were on the road beginning their season. Lord Baltimore manager and National Colored League vice president Joseph Callis trained his men hard for the upcoming season, but bad weather cancelled several practice games with the Mutuals, another African American club from South Baltimore. Rain drenched their final weekend of practices and the two clubs had to play a short four innings the following Monday afternoon to make up for it.

On May 5, 1887, a cloudy Thursday afternoon with a chance of light rain, the NCL began official play. A work-day crowd of around 400 showed up at Oriole Park to see the Lord Baltimores take on the Philadelphia Pythians. Bowers, the Pythians’ third baseman, got six hits as Philly jumped out to an early lead, but Baltimore was able to minimize the damage until the Lords could catch up and pull ahead. The crowd cheered when the Lord Baltimores took their bow at the end of the game to celebrate a hard fought, 15-12, victory. After a wild street parade and grand concert in Pittsburgh on Friday May 6, the New York Gorhams beat the Keystones, 11-8, before a big crowd of 1,200 black and white fans. The game was a huge success for the new league and got them rave reviews in sports pages across the country. It was the kind of good press money can’t buy.

The same day, the Lord Baltimores faced the Pythians again at Oriole Park. Hugh Cummings of Baltimore gave up only two hits but walked five and hit two batters. It wasn’t the smoothest performance by any means, but the Lords made it work. The Pythians added to their own demise with a crippling 10 errors that led to an 11-3 Baltimore victory. Enthusiasm was high, but the league was quietly in desperate trouble.

The Boston Resolutes had been in operation since the late 1860s and were the best African American team in New England. To get to their first game against the Louisville Forest Citys, they scheduled several exhibitions along the way to pay for the trip. The excursion didn’t go well. A huge storm system grumbled in from the west, cancelling games and stretching their budget. Travel expenses had gone through the roof as railroads lashed out with huge unannounced rate increases, sometimes doubling and even tripling overnight. The Resolutes failed to make it to Louisville in time for their first game. It was Kentucky Derby Week and railroads were taking advantage of the holiday crowds.

Barely making it in time for their second scheduled game and winning before a sparse crowd, the gate wasn’t enough compensation for the trip. The entire Boston club suddenly found themselves stranded without enough money to get to Pittsburgh, their next destination. The reality of the Interstate Commerce bill was becoming apparent to the baseball world just as the season got under way, and the American Association and National League struggled to adapt without discounted train fare. Some would use steamboats when possible to save money, but the havoc was unavoidable. Group rates would eventually return, but not in time to save the 1887 season from being a financial disaster for everyone.

The Lord Baltimores headed north to Philadelphia for a quick pair of games with the Pythians and lost twice. As they headed back home to meet their next foe, things had suddenly changed. The Pittsburgh Keystones received a telegram from A.A. Selden, manager of the Boston Resolutes saying that his team had been delayed and asked to reschedule for the next week. Boston had been on the road for 15 days already and had eight of them filled with rain. The one game in Kentucky was a disaster and the club was critically low on funds.

The Resolutes sent telegrams home asking for more money, but it hadn’t arrived yet. Selden advised Pittsburgh that the best thing for him to do was to pick up the Resolutes’ schedule in Baltimore. The Lord Baltimores met up at Oriole Park a few hours before their scheduled game versus the Boston Resolutes to stretch and have batting practice. Usually the visiting team would show up around noon and join in, but on Wednesday, May 11, that was not so. The Lords practiced alone.

When fans showed up at the park at game time, they were told there was an unexpected delay, and to please be patient. The home team and umpire had been nervously waiting for Boston to arrive for a several hours now and no word of a cancellation had been sent.

As the crowd grew restless and tired of waiting, the umpire declared a forfeit to Baltimore. Joseph Callis knew the Resolutes’ predicament, and out of good sportsmanship, he declined to accept the victory. Instead of letting the fans go home disappointed, the Mutuals, who were all in attendance to root for their friends, volunteered to play. The Lords won, 10-8, but the victory was empty. As the sun went down and the crowd left to go home, the Boston Resolutes still had not arrived.

The next day, the Lord Baltimores showed up early again to warm up, hoping that the Resolutes would be waiting at the gate, safe and sound, but no one was there. Joseph Callis hadn’t heard anything overnight, either. The Baltimore men took their practice in eerie silence, the crack of the bat echoing lonely down York Road toward the harbor. Something had gone wrong and no one knew anything.

Come game time, a sparse and curious Thursday crowd filtered into Oriole Park. As they were seated, they were asked to be patient once again. The Lord Baltimores stood on the home side of the field waiting to play, while the visitors’ bench remained empty. The umpire gave it a few minutes, but a second no-show seemed inevitable. A forfeit was issued to Baltimore and this time, it was accepted. As luck would have it though, the New York Gorhams reached Baltimore early and played a quick exhibition game to keep the fans happy.

The following morning it was discovered that the Resolutes were still stuck in Kentucky, and hope was fading that they’d be able to continue at all. The Gorhams beat the Lords, 15-3, in a poorly fielded contest in which Baltimore made 11 errors. The next day Baltimore rebounded to mangle the New Yorkers, 27-9, cranking out 20 hits in front of a good Saturday crowd. In Baltimore, at least, the NCBL was a success — as long as there was a visiting team to play.

Elsewhere, results were vastly mixed as news of the Resolutes misfortune circulated through the press.

The Lords played a thriller in Pittsburgh on May 16, coming from behind and scoring 15 runs in the ninth to beat the Keystones, 22-10. The next day, the tables were turned. Keystones second baseman Sol White recorded an unassisted double play. Pittsburgh rolled on to win the game and take another the following day.

And then suddenly, the schedule ran out. The missing Boston Resolutes had caused panic among league owners. The Pythians and Gorhams announced they were both leaving the league. The Pythians couldn’t afford the rent for the Athletics ballpark and suddenly had nowhere to play. Baltimore then refused to travel to Louisville after their poor treatment of the Resolutes was revealed. Despite best efforts to add Washington and Cincinnati as replacements.

Five days later, the National Colored League ceased to exist. It would take the Boston men over a month to get back home, and the veteran club disbanded soon after. The 1887 National Colored League was a bold attempt with bad timing. Any other summer and they’d have had a much better shot. Though this league failed prematurely, it was the first big break for many players who would go on to great careers and form the first wave of barnstorming teams that would blaze a path to the first Negro Leagues in the early twentieth century.

Author’s note

This article is based on a 2017 Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference presentation by Ken Mars with contributions from Mark D. Aubrey and John Thorn, and new statistics by Larry Lester.

Further information can be found in the author’s book Baltimore Baseball History: First Pitch To First Pennant 1858-1894 (Old Frog Publishing, 2018), and a research guide to the 1887 National Colored League which can be found in SABR’s Research Resources.