From Their Lips to Your Ears: Voices of the Game and How They Do It

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in SABR’s “Baseball Research Journal,” No. 25, in 1996 and is reprinted here in its original format.

By Mark Simon

With the growth of television and everything that comes with it (cable, satellite dishes, etc.), there seems to be less appreciation for baseball on the radio than there used to be, especially from younger fans. Most of my college friends have no desire to listen to an Ernie Harwell, a Ken Coleman, or a Gary Cohen. Yet, radio baseball play-by-play remains an art, and many people are enamored of the voices that have filled the airwaves. With this in mind, I thought I would talk to some of the many artists who paint or have painted the daily picture on the radio, and find out how they do their daily work.

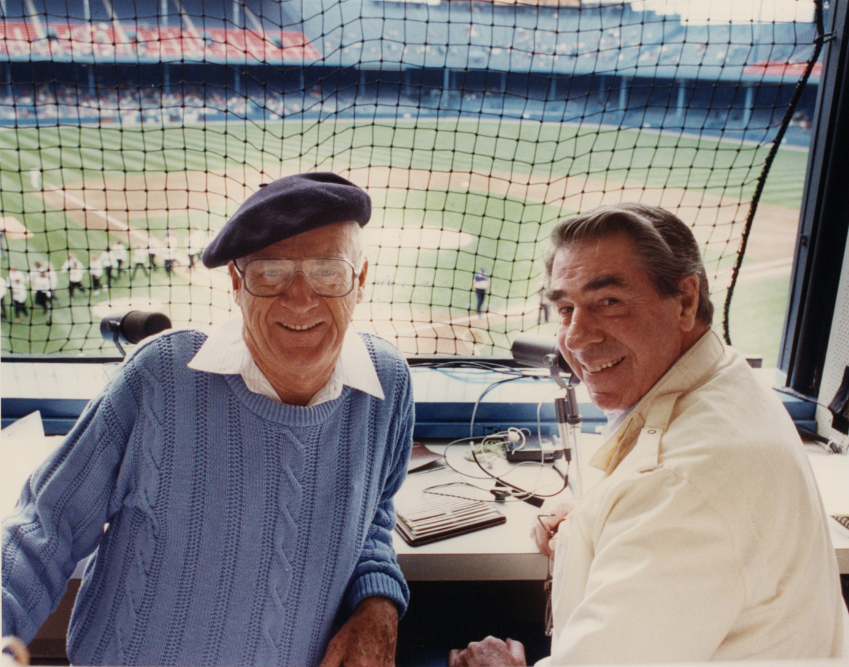

Detroit Tigers announcers Ernie Harwell and Paul Carey worked together in the broadcast booth for 19 seasons at Tiger Stadium. (Detroit Public Library, Ernie Harwell Collection)

PREPARATION

The motto of the big league broadcaster could be borrowed from the Boy Scouts: “Be Prepared.” There is nothing more important to a broadcaster than the preparation that he has brought to the booth.

“You don’t prepare for a baseball broadcast on the day of a game,” says New York Mets voice Gary Cohen. “You prepare by studying the game from the time you were a little kid. You can’t learn baseball as an adult. You can’t develop the love necessary for being a broadcaster as an adult.”

“When you’re doing baseball, you’re immersed in the game,” says former Red Sox broadcaster Ken Coleman. “You’re in it twenty-four hours a day seven days a week. You’re always preparing material you might use on a broadcast.”

One thing broadcasters consider an absolute necessity is a love for the game. “You have to have a love for the game,” Cohen says. “You have to have an understanding of the game. If you don’t, you’ll be exposed very quickly.” To enrich their understanding, many broadcasters read and keep files. Cohen reads six or seven newspapers a day, making notes as he goes along. Most broadcasters also keep index cards.

“I’ve always had an index card on every player, with basic stats, an anecdote or two, and some cards with stories I may want to recall,” says former Detroit Tigers broadcaster Ernie Harwell.

Kansas City Royals broadcaster and former college baseball player Denny Matthews keeps scouting reports on each player. “They come from the club,” he says. “I get them from the advance scouts. I evaluate players, too. Once you’ve seen them for a while, you know what they can or cannot do. Once you see them fifty to sixty games, you can evaluate them.”

With times changing, some broadcasters have gone to the electronic age. Red Sox broadcaster Joe Castiglione carries an electronic version of The Baseball Encyclopedia to every game. Broadcasters also make sure they have all the books they’ll need with them. The standard library includes the requisite scorebook (many of which are custom designed), a rule book, a record book, and the NL Green Book and/or the AL Red Book. The broadcasters are also supplied with lots of statistical notes and background by the ballclubs.

Some broadcasters keep extra material available. “I have a looseleaf notebook with all the Mets game-by-game results since 1962 just in case you need to jog your memory,” says Cohen. “I also have a pitchers line by line going back in some cases through their entire career.”

“I keep a home run book,” says Castiglione. “Where they went, who they were hit off. I also keep [track of] wall balls at Fen way.”

The part of preparation that most of the broadcasters enjoy most is what Cohen refers to as “kibitzing and talking.” Most broadcasters arrive at the stadium at least three hours before a game, and they sit and chat with whatever baseball people they can find. “The most fun time is hanging around the batting cage and the dugout,” says Castiglione. “That’s where you get a lot of information you can’t read in periodicals and journals.”

Some take advantage of every second they have to make sure they are adequately prepared. On the drive to and from the ballpark, Coleman listened to the innings he had broadcast. “I try to avoid using the same phrases too often. I try to check on my energy level, comfort level, pausing, and phrasing.” Much of this preparation is never used directly.

But the voices don’t think that their background work is a waste of time. “I may carry an item with me that I think is of interest for two to three weeks, but I have to wait for a situation to come up in a game that I can relate it to,” says San Francisco Giants broadcaster Hank Greenwald. “It may not happen for a while. You let the game dictate what you do.”

San Francisco Giants broadcaster and longtime SABR member Hank Greenwald was known for his wry sense of humor and gift for storytelling. He called Giants games from 1979 to 1996 and also announced for the Oakland A’s, New York Yankees, Syracuse University, and the NBA’s Golden State Warriors. (Courtesy of MLB.com)

CALLING THE GAME

The voices and styles of different broadcasters give the games they handle distinct flavors. Most don’t aim for a specific audience, because they feel this can be a distraction. Harwell is one who forms a composite picture. “There are all kinds of people you talk to. You have to please a college professor with your grammar and a veteran baseball player with your baseball knowledge. You have to introduce baseball to kids who have never been subjected to baseball before. You have to have material to appeal to the casual listener as well as to a real fan.”

Castiglione recognizes the older fans who are listening. “One of our great callings is to provide a service to the elderly, the blind, the shut-ins. We always try to keep those people in mind.” But he also realizes they need to pay attention to the young fans. “Every day someone is listening to a baseball game for the first time in their life, and you’re going to have a large influence on them if they enjoy baseball and learn from it.”

Baseball is a slow-moving sport and the good announcers have styles that allow the listener to take in all aspects of the game, while maintaining a solid rhythm. “My philosophy is that the game is paramount and that the announcer is secondary,” says Harwell. “Most people tune in not to hear Ernie Harwell, they tune in to know who is playing and what the score is.”

“My idea is to make the game as vivid as I can, with the description of each play,” says Castiglione. “You have to be ready to capitalize when there is action because most of the game is not action. You try to make it as descriptive as possible. No two ground balls to shortstop are exactly the same. If it’s an exciting play, you go back and recapitulate the play so people listening with half an ear can pick up what they may have missed.”

“[The person listening] has got to be able to see in his mind more clearly than if he’s watching on television because the imagination is more vivid,” says Greenwald. “I will try to start the description with the pitcher himself because it’s important for the listener to get a sense of timing. In his mind, nothing happens until the pitcher throws the ball. If you haven’t described the release of the ball, ‘The 1-2 pitch is fouled back’ is a bit abrupt.”

“Baseball is a game of peaks and valleys. It sort of runs along like life itself. There are big moments and there are very dull moments,” says Harwell. “I try to keep it as simple as I possibly can. The simpler the better. When you get too fancy, you find yourself in trouble. The play-by-play has to be laid out in brief, concise, simple terms. “When you do radio you have a canvas that is completely empty. You have to make use of the imagination of the listener,” he says.

Since a baseball game unfolds gradually, a broadcaster needs an intense focus to stay with the game. “It is so easy to let your mind wander,” says Cohen. “People ask me what qualities you need to do thisconcentration is at the top of the list.”

“When you are doing a game, your concentration level is such that you are completely involved in describing what you see,” says Coleman. “Thoughts flash in and out of your mind and you use them.”

Most broadcasters agree that being yourself is the most important quality that they can bring to the table. “I’m not one of those guys who goes completely bananas when a home run is hit or a double play is made,” says Harwell. “My voice will rise with the crowd and the excitement of the game. It has to be natural. It can’t be forced. “You don’t try to be funny, be an expert, be a manager, or be anything you aren’t. The best compliment anyone can pay you is that you sound like yourself-that you sound no different on the air than off the air. If you try to copy somebody, you’ll only be second best.”

“You have to be comfortable on the air and be true to yourself,” says Cohen. “The people most successful in this business are those who let their own personality shine through.”

While these announcers feel that what they say is important, they also feel that what they don’t say is very important. “Silence is one of the most effective tools an announcer can use,” says Harwell. “The fan needs a little rest for the ears, and I think a pause or silence can set up a play more dramatically than anything else.” Sometimes there is also a need for the announcer to “lay out” and let the crowd roar.

“Once you establish what happened, let the crowd do its thing because the people listening are probably doing the same thing,” says Matthews. “I’m not paid to yell and scream. I’m paid to tell you what happens so you can yell and scream.”

Every announcer has to deal with statistics. Some use them more than others. Some like different ways of using them. “The best way to deal with them is to relate them to something else, to humanize them,” says Greenwald. “Rather than saying Hank Aaron hit 755 home runs, I’d rather be able to say ‘If you measure the distance he covered circling the bases, it would be like a guy running from San Francisco to San Jose.’”

“I try to use as few statistics as I can. I don’t like to use too many statistics because when people listen they can’t absorb them. You can’t take all that stuff in at once,” says Harwell.

Statistics are just one of many ingredients that enhance a broadcast. “The easiest part of the business is to describe what happens on the field,” says Greenwald. “The toughest part is filling time between pitches, making that interesting to people. A sport like basketball carries the announcer, but an announcer has to carry baseball because nothing happens. The amount of time the ball is in play is less than five minutes. The rest is what you make it.”

Another way broadcasters fill time is through storytelling. Many broadcasters such as Waite Hoyt and Harry Heilmann, were well known for their tales and every broadcaster considers the story to be a valuable tool. “I’m pretty well known as a storyteller and believe in setting the game in a historical perspective,” says Harwell. “I might discuss the origin of the Texas Leaguer or why we have foul-pole screens. I don’t let it interfere with the play by play. I use that material early in the game, then later when the game begins to develop it becomes a story in itself.”

Most fans lose interest when a team is struggling. The announcer can’t. “There’s nothing like the excitement of a pennant race,” says Castiglione. “The excitement speaks for itself. But if you’re thirty games out in September, you still might see something today that you’ve never seen before. There’s always a reason to be interested.”

“Anybody can sound good if the team wins 100 games a year,” says Greenwald. “The real opportunity for you is when you have a bad team. If you get people saying the team isn’t really good, but these guys are fun to listen to, you’ve earned your stripes. [When the team is bad] you look at the season not in terms of the standings. Every day you may go out and see a terrific game. Even in the course of a 100-loss season most games are decided by one or two runs. Forget the standings. They’re not relevant anymore.”

Like anybody else, broadcasters have good days and bad days. “Some nights you’re not as sharp as others,” says Matthews. “Some days you’re really sharp, some you’re really dull. Most of the time you’re somewhere in between. The average listener probably doesn’t know, but I know.”

One thing that can make for a bad night is a string of broadcaster mistakes. But most have found that a mistake isn’t necessarily a bad thing. “The public forgives errors if they are human errors,” says Harwell. “[They] don’t forgive a lack of knowledge of the game, or someone who acts like he knows more than he does.”

“If it’s something silly, you try to make light of it,” says Castiglione. “It’s a good way to laugh at yourself and to establish yourself as a real person. People don’t like robots.” Even hard-core fans will tune in and out of games. This makes providing the score all the more important.”

“I try to pride myself on giving the score a lot more than anyone else,” says Harwell. “Because I feel, one, people don’t listen very carefully and when you give the score they don’t hear it, and two, a lot of people are in and out of the room.”

When the score is close, many fans like to second guess the decisions of the men on the field. But all of the broadcasters agreed that that was not part of their job. “The job is to report what you see. You’re not hired to coach or manage. You can suggest options or alternatives, but you’re not hired to second-guess,” says Coleman.

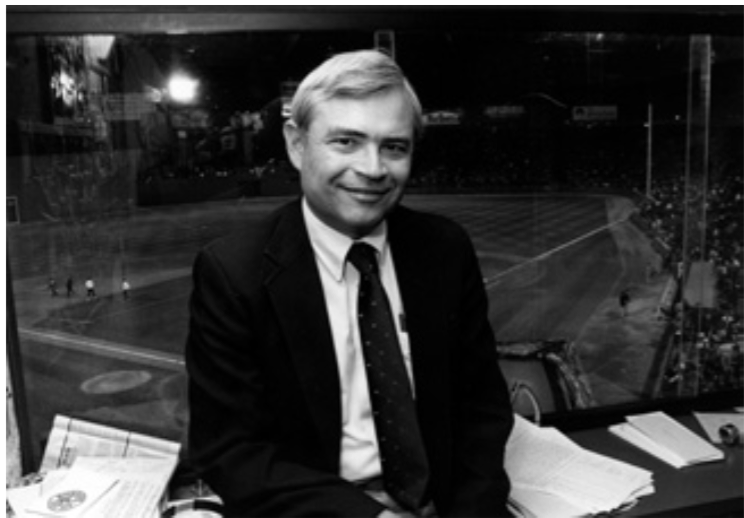

Joe Castiglione joined the Boston Red Sox broadcast team in 1983 and has spent more than three decades calling major-league baseball games. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

WRAP-UP

These men realize that they are providing an important service to many people and they get great enjoyment from carrying baseball through good times and bad. “Part of the attraction of baseball is the quality of soap opera,” says Cohen. “Each day relates to the one before it and the one after it. It becomes an interwoven fabric relating to what happened the day before, the week before, the month before. It all takes shape in an interesting fashion. It’s not just the broadcast of the game. It’s the broadcast of the season that’s the attraction to the listener.”

“You have to remember to have fun,” says Castiglione. “We’re not talking about disarmament or world events. The thing to remember is to have fun with it. It’s baseball. It’s a fun game.”

MARK SIMON is a senior research specialist for Sports Info Solutions. He is also a contributor to The Athletic and he has written for a variety of SABR publications, including the “Baseball Research Journal” and SABR books on the 1964 St. Louis Cardinals, 1969 New York Mets, and 1986 Mets and Red Sox. Previously, he was a digital publishing specialist for ESPN Stats & Information from 2002-18.