Gus Greenlee and the Crawford Grills

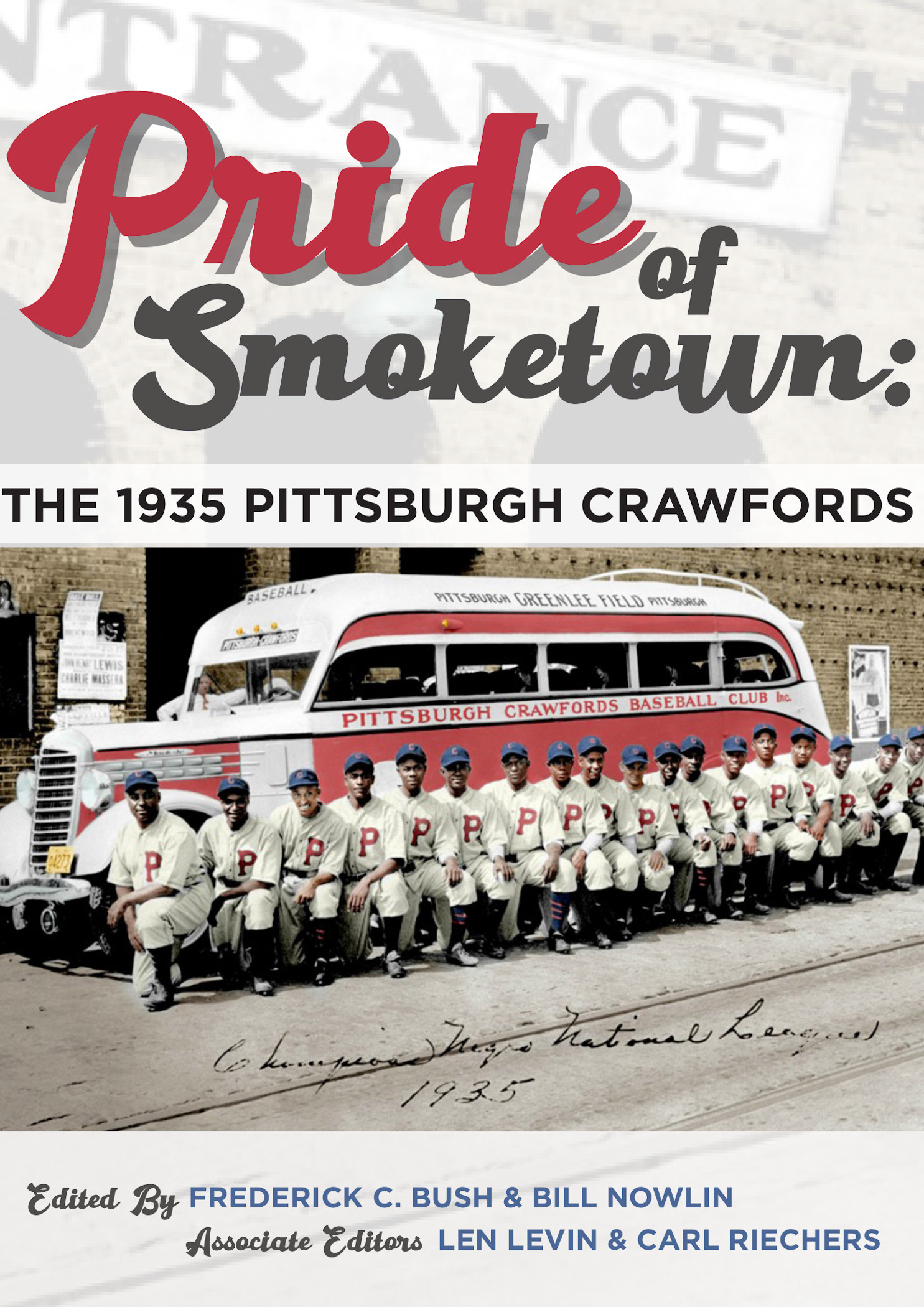

This article appears in SABR’s “Pride of Smoketown: The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords” (2020), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Baseball and music have a long history together. Many songs, such as “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” or “Talkin’ Baseball,” have been written specifically about the game. The National Anthem is played prior to every game, and music has long been played for fans throughout the game. In modern times, walk-up music for every batter has been added, and relief pitchers, especially closers, have chosen a signature song to announce their entrance into a game.

Baseball and music have a long history together. Many songs, such as “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” or “Talkin’ Baseball,” have been written specifically about the game. The National Anthem is played prior to every game, and music has long been played for fans throughout the game. In modern times, walk-up music for every batter has been added, and relief pitchers, especially closers, have chosen a signature song to announce their entrance into a game.

Historically, black baseball teams had a strong connection to their communities and jazz music. Bill “Bojangles” Robinson owned his own ballclub in addition to being a performer. Kansas City immediately comes to mind when one thinks of the jazz scene – especially with the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and American Jazz Museum now being located next door to each other – but another city with those same strong connections is Pittsburgh. The connecting figure was not a performer but an owner, Gus Greenlee, who not only owned the famous Pittsburgh Crawfords but also opened three Crawford Grills in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. At the Grill, ballplayers and musicians hung out together, creating an entertainment community for themselves and anyone who came out to listen. The story of Greenlee, the Grills, and the Crawfords is not often told, but is a part of the history of the city and the team. Greenlee’s importance to the music scene, as well as the local baseball scene, cannot be overlooked.

Gus Greenlee was born in 1897 in Marion, North Carolina. He moved north to Pittsburgh in 1916 to look for work. Greenlee ended up serving in France during World War I and, when he came back to Pittsburgh, had saved enough money to be able to buy a cab. Not only did he provide rides, but he sold alcohol from the cab during Prohibition. The added income allowed Greenlee the chance to buy his first club, The Collins Inn, which he renamed the Paramount. Greenlee used the Paramount as a place for gathering, introducing jazz musicians such as Edna Lewis, and as a front for his numbers game. Greenlee became the king of the hill and was the go-to source for loans, mortgages, college funds, placing simple bets, and so much more.1

Greenlee added to his growing economic empire by becoming a sports promoter, primarily for boxers. His premier boxer was light heavyweight champion John Henry Lewis. He also became the owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a semipro team known as the Crawford Colored Giants at the time Greenlee purchased the franchise. He entered the Crawfords into the Negro Leagues in 1932 and the team won championships in 1935 and 1936. To help promote the team, he paid for the construction of Greenlee Field, which opened in 1933 at an approximate cost of $100,000. The park could seat up to 7,500 and was also used for boxing and college football when the Crawfords were not in town. Greenlee was also the architect of the annual East-West classic at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, which began in 1933, the same year as the first major-league All-Star Game, and helped to put the Negro Leagues on the map by becoming an annual showcase for its biggest stars.2

In addition to his sports activities, Greenlee made his mark on the community and the music world when he opened the first Crawford Grill in 1931. His success led to the opening of a second Grill in 1943 as well as a third grill that operated for a short period in 1948. Each of his clubs opened in a different section of the Hill District, following some of the changes that occurred in the city as its people and businesses adapted to the Great Depression and World War II.

Crawford Grill No. 1 operated from 1931 to 1951/52 when a fire forced the club to close. The building then had to be torn down because of the damage and cost of repairs. Crawford Grill No. 2 kept its doors open from 1943 to 2002; two decades later there were efforts to try to reopen the Grill as a historic landmark. The third grill operated only seven years, from 1948 to 1955, and never gained the popularity of the first two. Two reasons might account for the shorter life span. The Hill District changed after World War II: People continued to move in and out of the area as soldiers came home and took advantage of the GI Bill. The bigger concern was the building’s location on the outer edge of the Hill District. The first two Grills were more accessible because they were located in the heart of the community along Wylie Avenue in the lower Hill District. Each section of the Hill District had its own identity, but the people all shared strong connections to the business community due to segregation. They supported what they had so they did not need to leave to find the products needed.3

All of Greenlee’s ventures benefited from the presence of the Pittsburgh Courier in the Hill District (operated 1910-66). The Courier writers helped promote and advertise businesses in their weekly columns. For example, John Clark had a column titled “Wylie Avenue” in which one could read all about the happenings at every business on that main thoroughfare. Lee Matthews’ column “Swingin’ among the Musicians,” informed everyone as to who was playing where each night of the week.4

Crawford Grill No. 1 began life as the Leader House. When Greenlee bought the club it already had a reputation in the jazz community; the Louis Deppe band played there. Deppe not only played at the Leader House but his band toured Ohio and West Virginia. Greenlee renamed it when he purchased and opened his new club in 1931. It became the meeting place for Crawford players after games and on offnights. On any given night, local folks could stop by and they might see Satchel Paige hanging out with band leader Billy Eckstine or pianist Mary Lou Williams. The Grill had three floors and took up an entire city block. The main music area had a revolving stage, perfect for small combos, with a glass-topped bar. The third floor housed “Club Crawford,” which was reserved for insiders only. Those given entrance might be there for a special music performance or sports betting, a theme night, or even the numbers game at higher stakes. Greenlee invited all the Negro League owners to the Grill for their business meeting in January 1934.5

Greenlee and William “Woogie” Harris were two of many individuals involved in the numbers game – the local street lottery – in Pittsburgh. At one point Greenlee was estimated to be making $20,000 to 25,000 a day from his numbers racket. A person could place a bet for as little as a penny and make $5 if his three digits hit that day. The small amount required to place a bet made the game accessible to all. Greenlee was the go-to person in the Hill District because he always paid out while some other numbers racketeers had reputations for stiffing their clients. Greenlee had a reputation for helping those who were in need in the Hill District, and his generosity benefited him, too, as it made his clubs all the more popular as gathering places. There might have been better music elsewhere in the city, but the Grills were always the place to hang out and meet people.6

Over the years many famous musicians passed through the Grills and several local sensations got their start there. Big-band members came late at night to join the jam sessions with the locals, and cast members from local theaters came out after their shows. Nationally known jazz musicians regularly stayed in Pittsburgh for weeklong gigs because of the vast array of venues where they could play. Greenlee’s Grills were part of a large scene that included such places as the Savoy Ballroom, the Pythian Temple, the Bambola Social Club, and the Hurricane Club. The Roosevelt Theater brought in some of the biggest names such as Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, and Ray Brown.7 In the early years Greenlee liked to bring in musicians from New York City, such as Jean Daniels and Jack Spruce and his septet, to create a vibrant and busy club scene. Nelson Harrison, a jazz musician, had this to say about the Grill: “The Crawford Grill didn’t pay [hardly] any money. It was just the place to play … [but] everybody who was anybody was in your audience.”8 For a period at Grill No. 1, Greenlee even brought in a New York City chef and redecorated so the place so that it looked like a Spanish hacienda, which gave it a unique feel compared with all the other clubs people could frequent. Later, Grill No. 2 shifted to smaller combos and solo artists, such as Ted Birch and Bobby Dummit, as the music scene moved away from big bands.9

Gus Greenlee, promoter of a light heavyweight boxer and owner of a championship baseball team, brought national fame to his community. As owner of a café, a pool hall, a music booking agency and the Crawford Grill, Greenlee was integral to the music scene, giving many young musicians their start. Additionally, as one of the most respected numbers runners, he really was the King of the Hill. Though the Grills may no longer be around, they are still a part of the history of Pittsburgh.

LESLIE HEAPHY is an associate professor of history at Kent State University, Stark, chair of the Women in Baseball Conference for SABR, and author/editor of numerous books and articles about women’s baseball and the Negro Leagues.

Notes

1 Pittsburgh Courier, July 8, 1933: 70; James Bankes, The Pittsburgh Crawfords: The Life and Times of Black Baseball’s Most Exciting Team (Dubuque, Iowa: William C. Brown, 1991).

2 David M. Brown, “Crawfords’ Owner Sinner and Saint,” Pittsburgh Tribune Review, February 10, 2008.

3 Colter Harper, “The Crossroads of the World”: A Social and Cultural History of Jazz in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, 1920-1970 (MA Thesis, Duquesne University, 2001), 43.

4 Harper, 50-51.

5 Greenlee obituary, The Sporting News, July 23, 1952: 30; Harper, 65, 103.

6 Harper, 92-94; Michael Santa Maria, “King of the Hill,” American Visions, June 1991: 21-24.

7 Pittsburgh Music History, sites.google.com/site/pittsburghmusichistory/pittsburgh-music-story/jazz/hill-district; Harper, 117.

8 “Crawford Grill Hosted Jazz Legends,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 12, 2003.

9 Harper, 100-101, 105; Ron Ieraci, “The Crawford Grill – A Pittsburgh Jazz Legend,” Old Mon Music, November 29, 2008, oldmonmusic.blogspot.com/2008/11/crawford-grill.html.