Gus Greenlee and the East-West All-Star Game: Origins and Conflict (1932-1944)

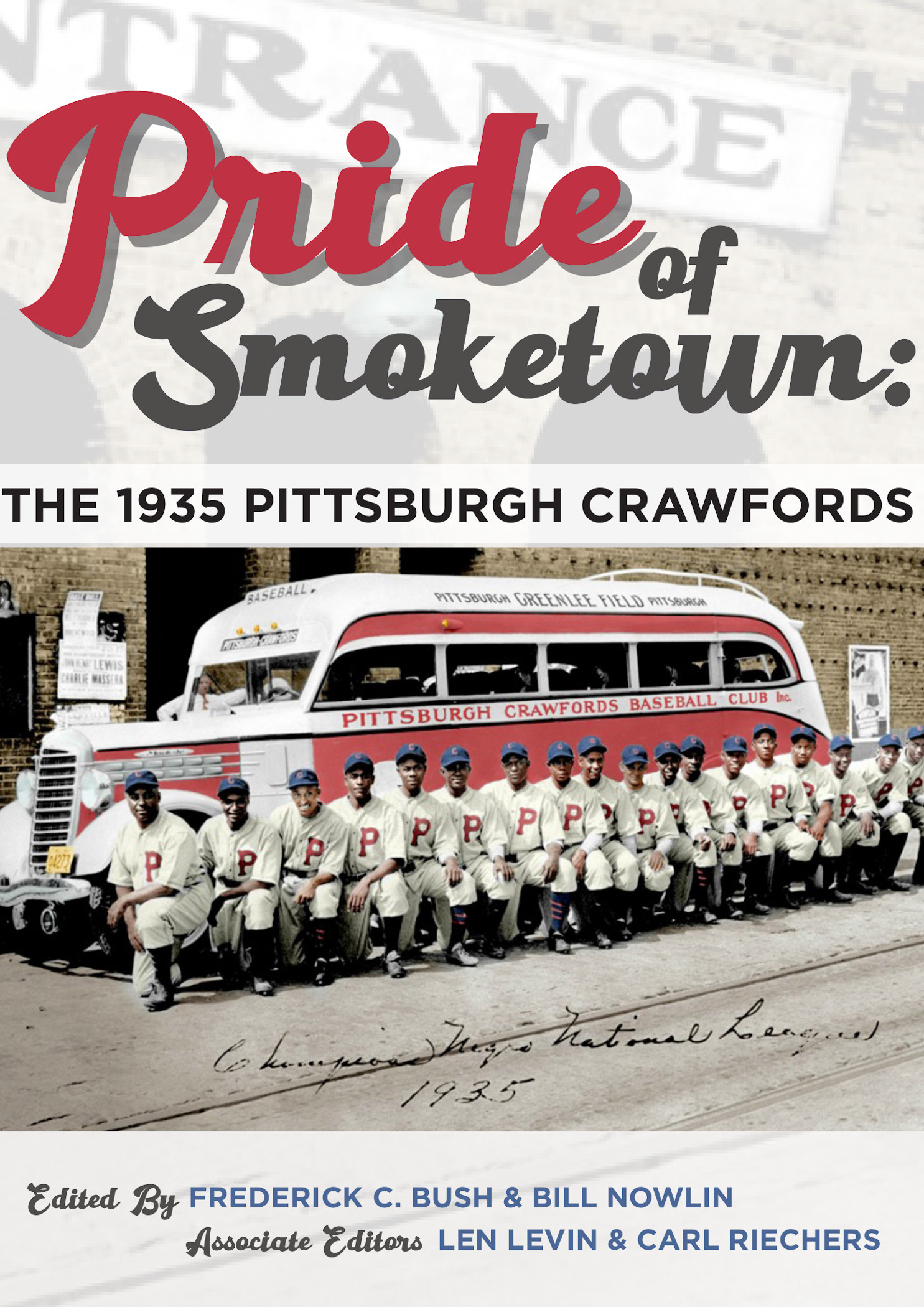

This article appears in SABR’s “Pride of Smoketown: The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords” (2020), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Introduction

Introduction

“Since the August Day in 1933, when ‘King’ Cole of Chicago, Gus Greenlee of Pittsburgh, and Tom Wilson of Nashville, saw a dream, which originated in the minds of Roy Sparrow and Dave Hawkins, come true, the East-West game has grown by leaps and bounds until it now rivals the annual National versus American League All-Star Game.”1

The above quote, which appeared in the August 26, 1939, edition of the New York Amsterdam News, provides a simplified version of how the annual signature event of the Negro Leagues, the East-West (E-W) All-Star Game, came to be. In this account, Pittsburgh Crawfords owner and Negro League head honcho William A. “Gus” Greenlee was one of several individuals who played a role in the creation of an all-star game that rivaled, and sometimes surpassed (in attendance and, arguably, importance), that of the major leagues.

There are many conflicting versions of the birth of the “big idea”2 of the Negro Leagues that need to be sorted to separate fact from fiction. Like many stories of conception, in baseball and elsewhere, the E-W Game truly had many “fathers.” Greenlee, though, was undoubtedly the most influential of the many creators – and developers – of the E-W Game. His control of the game’s presentation and revenue distribution was a source of contention from the first such contest in 1933 through the sixth edition in 1938. Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords withdrew from the Negro Leagues in 1939, but his involvement in battles over the distribution of its proceeds again became an issue in 1944, when Greenlee encouraged Negro League players to threaten a strike in order to obtain “reasonable” compensation from Negro League owners.

Greenlee was the driving force behind the establishment of the second Negro National League (NNL) in 1933. He became the first chairman of the 1933 edition of the NNL and was credited with “spreading the word in various cities of the new league’s advent.”3 Before that, Greenlee had started out his involvement in Black baseball by purchasing the semipro Pittsburgh Crawford Giants in 1930. In 1932 he built Greenlee Field, one of very few ballparks owned and operated by a Black franchise, and competed in the 1932-only East-West League, which was the brainchild of Greenlee’s Pittsburgh-area counterpart, Cumberland “Cum” Posey, who owned the Homestead Grays, a longtime NNL rival of the Crawfords.

Prior to 1933, when the major leagues and the Negro Leagues each played their first league All-Star Games, teams of stars occasionally were formed. In the major leagues, an assemblage of stars from seven teams played the Cleveland Indians on July 24, 1911, as a benefit game for Hall of Fame Indians pitcher Addie Joss’s widow after Joss died at age 31 of tubercular meningitis early that year. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, teams of Black and White players were pitted against each other, usually (but not always) in the baseball offseason; according to eminent Black-baseball historian John Holway, the Black teams won 269 of those contests, lost 172, and tied one.4

In 1932 an example of a White team playing a Black team occurred in early October when Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords played a series of games at Greenlee Field against “the National League All-Stars, featuring some of the best players of the leading teams of the National League this season.”5 According to the Pittsburgh Courier, “Casey Stengle (sic), formerly of the New York Giants is handling the club and is anxious for a win over the Greenlee outfit.”6 As it turned out, “[D]espite the big bats of Hack Wilson, English, Todd, and the strong arms of Larry French, Swift, Parmalee and the rest” the Pittsburgh Crawfords won the series, five games to two.7

In the 1930s, the Crawfords themselves were a bit of an all-star assemblage. At various times they featured future Hall of Famers Leroy “Satchel” Paige, Josh Gibson, James “Cool Papa “ Bell, Oscar Charleston, and William “Judy” Johnson, along with legendary Black stars Herbert “Rap” Dixon, Jimmie Crutchfield, Elander “Vic” Harris, and 1933 E-W All-Star Game East squad starting pitcher Sam Streeter. Not surprisingly, then, when the first E-W contest was played, 12 of the 17 players named to the East squad played for the Crawfords.8

Whose “Brainchild” Was It?

According to Robert Peterson in Only the Ball Was White,

“Gus Greenlee fathered the East-West game, promoting the first one in 1933 in cooperation with Robert A. Cole of the Chicago American Giants. The idea for the game came from Roy Sparrow, one of Greenlee’s employees, who dreamed it up in 1932, the year before the first major league all-star game, which played in Chicago under the auspices of the Chicago Tribune. Greenlee handled the promotion and took ten percent of the East-west game receipts until he had a falling out with the other owners and resigned the presidency of the [Negro] National League in 1939.”9

As has become apparent in the interim, Peterson’s seminal work is incomplete both in its characterization and timing of Sparrow’s “idea” as well as Greenlee’s compensation for his role in developing and promoting the game.

Where, then, did Robert Peterson find evidence to conclude that Roy Sparrow had first conceived of the East-West Game in 1932? The answer to this query can be found in the Black press. Several noted columnists, some of whom were participants in the NNL’s operations, wrote stories in the 1940s that presented their version of the origin of the E-W Game. In 1941, then- Pittsburgh Courier managing editor William G. Nunn wrote:

“The writer has followed the East-West classic from a stormy wintry night in 1933 until the present. He was present at the birth of the idea, along with W.A. “Gus” Greenlee, whose fertile and imaginative brain furnished the “key.” … Roy Sparrow, who first conceived the idea and passed it along to Greenlee: John L. Clark, former Secretary of the Negro National League; ‘See’ Posey, now with the Homestead Grays and Ches Washington, Sports Editor of this paper.

TOOK A GAMBLE

“We have followed the growth of the Greenlee-Sparrow ‘dreamchild.’ We know that in 1933 it was Greenlee, Tom Wilson, now president of the N.N.L.; R.A. Cole, now head of the Metropolitan Burial Association and Hall, present boss of the Chicago American Giants, who backed and went along with the idea.

“We know that these men gambled” (sic) and won for Negro baseball. And we can’t forget that the idea could have grown out of the game which Dave Hawkins staged in Cleveland in 1932.”10

Nunn could forget the year that Dave Hawkins staged a game in Cleveland – Hawkins’ “One Big Day” was held in 1933, not 1932. Perhaps Nunn also was “forgetting” when the discussion he purportedly engaged in happened.

It is not only Nunn who stated that the original idea for the E-W Game came from Roy Sparrow. Randy Dixon, who usually wrote for the Philadelphia Tribune but in this instance appeared in the Courier, mentioned that Nunn “sat in the conference that gave birth to the East-West Idea” and then added parenthetically “(although Roy Sparrow spouted the thought from his fertile and active conk).”11 Perhaps Dixon may have been taking the word of Nunn, whose above statement was published two weeks before Dixon gave credit to Sparrow, adding that Nunn “rates as the most hep newsman in the profession. He knows all the questions and answers all the answers.”12

But there were at least three other voices that add support to the contention that Roy Sparrow “planted the seed” for the E-W Game, then saw it developed by Gus Greenlee and others – none other than Greenlee’s bitter rival Cum Posey, noted Black sportswriter Wendell Smith, and, in an earlier version, American Negro Press sportswriter Alvin Moses.

It is Posey’s version of the E-W Game’s conception that has been sourced by two of the most esteemed historians of the institution of Negro League Baseball (Neil Lanctot) and of the history of the East-West Game from 1933 to 1953 (Larry Lester). Lester, in his book Black Baseball’s National Showcase, asserted that “[t]he East-West All-Star game was the brainchild of writers Roy Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph and Bill Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier.”13 Both Lester and Lanctot referenced Cum Posey’s column “Posey’s Points” of August 15, 1942, as their primary source for crediting Sparrow with the idea of a contest between Negro League stars of the East and West.14

On the eve of the 10th E-W game in 1942, Posey published his version of how the game came to be, suggesting that other versions did not tell the entire genesis of the game: “The idea was born at a conference in Loendi club, Pittsburgh. The writer of the column had invited Roy Sparrow … and Bill Nunn … to talk over the possibility of having two All-Star Colored Teams feature the Annual New York Milk Fund Day at Yankee Stadium. This idea was a pet idea of Roy Sparrow.” (emphasis added)15

Posey went on to say that, after some discussion, the three decided on a North-South contest at Yankee Stadium, but Nunn and Sparrow shared this idea with Gus Greenlee on the same July 1933 night of the Loendi club meeting. According to Posey, Greenlee, his “bitter rival,” persuaded Sparrow and Nunn to adopt Greenlee’s version of this idea, transforming it into an East-West rather than a North-South contest and playing it in Chicago’s Comiskey Park, where the first major-league All-Star Game had just been held, rather than in New York City.16

Two years prior to the conception stories of Nunn, Dixon, and Posey, Alvin Moses had described the birth of the E-W idea happening on Wylie Avenue in Pittsburgh on a “mid-summer afternoon in 1933. Roy [Sparrow] is chatting chiefly about baseball with the then Negro National League president, Tom Wilson, Rufus Jackson, and Gus Greenlee. The conversation centered around ‘why shouldn’t colored players at least be permitted to show their wares to colored and white fans alike in parks like Comiskey Field [sic], Chicago, or Forbes Field, Pittsburgh?’ At the time, Sparrow was writing for a leading white newspaper and in a key position to broach the idea.”17 Moses went on to describe how Sparrow convinced key individuals in the White community of Chicago to come aboard and support the event.18

Finally, Wendell Smith’s 1943 version places Sparrow on the scene in the winter of 1932: “The idea for this extravaganza was conceived here in Pittsburgh in the winter of 1932. It was not an idea of any particular individual, but it took Roy Sparrow, now critically ill in a local hospital, to ‘sell’ the idea to Gus Greenlee, who was the ‘angel’ of the promotion. Sparrow, Cum Posey, Greenlee, and William G. Nunn, now managing editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, first saw the possibilities of the ‘dream game.’”19 It seems likely that Robert Peterson drew upon influential African-American sportswriter Wendell Smith’s account in dating Sparrow’s initial role in the E-W Game’s conception to 1932.20

So how did Dave Hawkins enter the discussion? Hawkins promoted a doubleheader match called “One Big Day” that was played on Sunday, July 23, 1933, between the Chicago American Giants and the Pittsburgh Crawfords in Cleveland’s League Park, which was used by the Cleveland Indians for their home games in part of 1932 and again in 1934 but not in 1933.21 Hawkins was a Cleveland-based promoter, but he was bedridden in North Carolina when One Big Day was actually staged.22 Although Bill Nunn was in fact one year off when he stated that Hawkins’s promotion occurred in 1932, one can speculate that he remembered wrongly because it seems odd for such a game to be a catalyst for the first E-W Game being played – July 23, 1933, being virtually the same time that the inaugural E-W contest was announced in the Black press. Nevertheless, several commentators have given Hawkins partial credit for “birthing” the idea of the E-W Game, and part of the reason is likely that they were aware of Hawkins promoting his Cleveland doubleheader well before the E-W Game was declared in the Black press. In W. Rollo Wilson’s Pittsburgh Courier column of August 5, 1933, he described the genesis of Hawkins’s promotion as being a desire to “sell Negro baseball to white newspapers and white fans.”23 According to Wilson, in the winter of 1933 Hawkins first tried to get White broadcasters and writers interested in the “proposition of admitting Negroes to the ranks of Organized Baseball.” Shortly thereafter, Hawkins tried to get Negro League baseball scores announced on broadcasts once the NNL was formed that year. When Hawkins got no cooperation in this effort from league officials, he turned to promoting a “big game” (which became a doubleheader), a promotion that involved gaining “buy-in” from the Indians and city officials along with the Cleveland dailies. He then negotiated the park fees and the share of receipts for the competing teams, as well as the ultimate choice of the Crawfords and the Giants as the protagonists, as there had been a time when the New York Black Yankees rather than the Giants were being considered.24

In the end, the Crawfords swept a doubleheader from the American Giants, 8-1 in the first game and 13-12 in 12 innings in the second contest. In the first game, Giants pitcher Sam Streeter bested Willie Foster, giving up only four hits and one run, compared with 14 hits allowed by Foster. These same two pitchers would start the first E-W Game seven weeks later. In the second game, Josh Gibson hit for the cycle, tying the game at 12-12 in the ninth inning with a home run, before Cool Papa Bell drove in Jimmie Crutchfield with the 13th and deciding run with a “crashing single.”25 Attendance was approximately 7,000, “one of the biggest turnouts in the history of Negro baseball and one of the most enthusiastic and appreciative crowds ever to witness a struggle between two of America’s best diamond aggregations.”26 Hawkins himself could not attend the game, as he was laid up in a veterans hospital in North Carolina, but he sent a telegram that was read out to the crowd, which included “many of Cleveland’s civic and political celebrities. …”27

Hawkins continued to lend his talents to promoting future E-W games, most notably writing a folksy letter in 1934 that was printed in the Pittsburgh Courier in a column by NNL league secretary John Clark; in the column, Hawkins provided his suggestions of “pitchers for the koming klouters ALL-Star Baseball Klassic.”28

In sum, the genesis of what became the annual signature event of Negro League history included several motivating factors. First, there were contests between Black and White baseball stars, and perhaps undeveloped ideas like those of Roy Sparrow prior to 1933. Second, the intense competition being developed in this first season of the second NNL stimulated Dave Hawkins to successfully promote the “One Big Day” doubleheader between the American Giants and the Crawfords, which became a prototype for the first E-W Game. Contemporaneous with Hawkins’s planning of his Cleveland doubleheader, Chicago Defender columnist Doyle Clivelle wrote that Giants owner Cole and Crawfords owner Greenlee “‘Should Sell’ That Foster-Page [sic] [Chicago American Giants pitcher Willie Foster and Pittsburgh Crawfords pitcher Satchel Paige] Diamond Feud” by “printing the things Foster and Page are supposed to have said to each other the last time they met on the field” and thereby build a big rivalry.29 Finally, the major-league All-Star Game played in Chicago on July 6, 1933, likely gave rise to meetings that Posey claimed to have had with Roy Sparrow and Bill Nunn and to a “call to action” for Gus Greenlee to stage a Chicago version of “One Big Day” that pitted East teams against West teams. In fact, the first E-W Game, on September 10, 1933, was primarily played by Eastern players drawn from the Crawfords against Western players drawn from the American Giants. And though Satchel Paige did not pitch in the 1933 E-W Game, he faced off against Willie Foster in the final three innings of the 1934 contest, won by the East, 1-0.

1933 – From Arch Ward’s Major League Classic to Gus Greenlee’s Inaugural East-West Classic

Chicago Tribune sportswriter Arch Ward conceived of the first major-league All-Star Game, held on July 6, 1933, at Chicago’s Comiskey Park in connection with the 1933 World’s Fair. The American League stars defeated the National League, 4-2, in a game that featured a two-run homer by Babe Ruth. Eighteen years earlier, sportswriter and Baseball Magazine editor F.C. Lane had been hit by an inspiration: Stars of the two leagues ought to play a seven-game series against each other the week of July 4, which would be the “grand opera of baseball” and “might readily be staged in midseason, where it would serve not only as the grand scenic display of the year, but stimulate greater interest in the pennant race.30 According to Lew Freedman, “[C]ertainly Ward was aware of the merits of Lane’s suggestions.”31 Undoubtedly, Gus Greenlee and others were aware of the excitement attendant to the playing of a contest between teams of star players, and articles in the Black press indicate as much.

Ches Washington, in his “Sez” Courier column of June 17, 1933, wrote that “several prominent business men” were considering “the bringing together of the major league’s super greats and the Negro League’s most brilliant stars for the biggest battle of baseballdom” – and that this attraction would be connected to the Chicago World Fair.32 Washington went on to say that “[T]he idea is somewhat in keeping with the nation-wide poll to select All-Star major leaguers who will clash at the Fair. …”33 It makes sense that one of those businessmen would have been Greenlee, who was not only the owner of one of the powers of the newly established NNL but was also the league’s chairman.

Despite Washington’s view that “the rivalry and interest would be at a much higher pitch for a mixed or inter-racial diamond clash than in a contest where there is no color line,” the NNL instead moved on to develop an all-star contest within the Negro Leagues.34 On July 22, 1933, a Pittsburgh Courier piece headlined “Here’s Posey’s Idea of an All-East, All-West Team” listed Cum Posey’s roster choices “if the East could meet the West in an All-star colored baseball game.”35 It was not until July 29, 1933, that the Black press first announced the playing of an all-Black, all-star baseball contest:

“The ’dream game’ of Negro baseball is going to be staged! Late advices from the offices of the Negro National Association indicate that two crack teams, to be selected by popular vote, will play in a big colored classic at Comiskey Park in Chicago on September 10.”36

There is little more than speculation as to whether or not Posey had already gotten wind of Greenlee’s supposed co-opting of Posey, Sparrow, and Nunn’s North-South conception when Posey was quoted with his player choices for East and West teams. We do not know for sure when Greenlee, American Giants owner Robert Cole, future NNL President and Elite Giants owner Tom Wilson, Sparrow, and Nunn began the process of negotiating for a game date at Comiskey Park and developing a method of promoting the first E-W contest, but it must have begun before the end of July of 1933.

Sportswriter Rollo Wilson provided the most insight into Greenlee’s preeminent role in successfully staging the 1933 E-W game. Wilson was not only a columnist for the Pittsburgh Courier, but in 1934 he was named the NNL commissioner, a salaried position (which was not a given in Black baseball of the Depression era), in which his chief responsibility was to arbitrate legal disputes, a job for which his chief qualification was his perceived impartiality.37 Less than one month after the first E-W Game, Wilson’s regular column, “Sports Shots,” positively depicted the role of Greenlee in being “that rare type of sportsman – one who will spend his money in the game and send more good dollars after the ones which have gone beyond recall.”38 As Wilson recounted Greenlee’s seminal role in forming the second incarnation of the NNL, he wrote that Greenlee “conceived the idea of an East-West game, the players to be selected by the vote of the fans and he had to put $2,500 on the line weeks before the date of the game. All that he has received for his efforts has been ill-advised criticism … even from the very men who accepted his money to pay their personal bills.”39 Eleven years later, Wilson wrote another column about Greenlee’s trailblazing role in Black baseball in which he referred to Greenlee as “the father of the East-West game and it was his money which guaranteed the owners of the White Sox park that they would get their excessive rental.”40

Whether or not Rollo Wilson was impartial when it came to Gus Greenlee, he made three important points in his columns regarding Gus’s organizing role in the inaugural E-W Game: Greenlee was really the game’s creator, he bankrolled the contest, and he was criticized heavily for the game’s execution. In 1951, as Greenlee’s life was winding down due to a lengthy illness, Wendell Smith summed up Greenlee’s contribution as follows: “He launched the first game, invested his own money, and eventually made it an affair of national significance.”41 In his seminal book Negro League Baseball, Neil Lanctot concluded that “it was reportedly Greenlee who took the greatest risk by paying $2,500 in advance for the exorbitant rental of Comiskey Park” for the first E-W contest.42 While it is not clear whether Greenlee ended up paying the entire fee out of his own pocket, Wilson did make it clear that Greenlee fronted the money to reserve the park.

Wilson’s counterpart, John Clark, was another person who participated in some fashion in the organization of the E-W Game. Clark was not only a regular columnist for the Pittsburgh Courier, but he was also a front-office employee of the Crawfords and Greenlee as he was the NNL secretary. One could presume that Clark, as both a league and Crawfords official, would have had an informed idea of whose money was spent and who shared in the proceeds. It was Clark who reported that “all expense of promoting the game will be borne by three club owners, namely W.A. Greenlee, R.A. Cole, and Tom Wilson.”43 Later in the column, Clark stated that the 1933 “East-West experiment, which cost over $5,000 before the park gates were opened on September 10,” garnered a net profit of less than $400 to each of the three owners.44 While Clark was describing the 1934 game’s promotional expenses in this column when he named the three owners, it is easy to conclude from a careful reading of the rest of his column that those three owners also shared in the 1933 expenses. Does Clark’s reporting of an equal division of the profits mean that Chicago American Giants owner Cole and Nashville Elites owner Wilson partly reimbursed Greenlee for his payment of the expensive Comiskey Park rental? According to Greenlee:

“Tom Wilson, R.A. Cole and myself took the first gamble in 1933. That year we couldn’t get anyone to go in with us. The game drew 12,000 people.

“The next year, the three of us promoted the game, giving the league ten percent. We paid all expenses. …

“We gave the league the East-West game, after we struggled and sacrificed to put it over. When no one had any faith in the idea, it was perfectly all right for us to gamble with our money’ …”45

While it is uncertain whether or not Greenlee’s “gamble” included his payment in full of the park rental, it is known approximately how much revenue the first E-W Game generated. The Courier reported in 1941 that $9,500 was received from fans attending the game.46

For Greenlee, his partners Cole and Wilson, and his media assistants Nunn of the Courier and Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Sun-Gazette, August and September 1933 were a very busy time. Sparrow in particular was very busy promoting the game, as he “not only barraged 55 black weeklies with news of the upcoming game, but also contacted 90 white newspapers.”47 And there was more. Sparrow engaged Norman Ross, who interested “big name movie stars and executives” while he “personally conducted fifty-one broadcasts” and “placed the East-West directly in the lap of Chicago World’s Fair officials who went for it, hook, line and sinker.”48 Meanwhile, various prominent Black newspapers, including most notably the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier, were printing ballots for the fans to vote on who should participate. The Courier reported on August 12, 1933,

“The almost phenomenal response on the part of fans and followers of Negro baseball is evidenced by the heavy voting which marked the first few days of the contest to select the nation’s best players to represent the East and the West in the Comiskey Park battle.”49

Both the Defender and Courier reported that the game would be a doubleheader. The Defender stated that the first game would be the official game, and the Courier reported, “[I]n case of a split victory in the doubleheader, the third game will be played in an Eastern city which will be designated later.”50

In the end, only a single game was played on September 10, 1933, with the West squad defeating the East, 11-7. Although the game was well attended,51 it was preceded by much “ugly talk” regarding the methods of choosing players and the game’s receipts going “into the pockets of the promoters.”52 Philadelphia Tribune sports editor Randy Dixon, a notable (but also humorous) scolder of Negro League owners, described the game as “basically a commendable idea” but one suffused with “promotorial [sic] greed” resulting in an “over-commercialized stench” which was intended to make money for the backers rather than providing a true test of the playing abilities of Eastern vs. Western players.53 After the contest, Cum Posey perceived the first E-W Game as “not a true estimate of the strength between East and West” which he believed would have been better as a Crawfords-American Giants game, but he also said that “the promoters … put up all the money and deserved all the profits.”54 Posey later developed a different opinion about the handling of East-West revenue by Greenlee and his partners.

1934-1938 – Greenlee and His Partners Challenged – and Extolled – While the Game Becomes an Institution

1934 – There Will Be a Second E-W Game – and There Will Be Conflicts

At the end of the 1933 NNL season, Rollo Wilson, not yet the commissioner of the NNL but an informed observer of league operations, portrayed Greenlee as essentially the savior of a fledgling operation: “[O]ne thing and another conspired to stop the circuit but Greenlee and his bankroll shifted clubs, cities and players and kept the thing going somehow or other.”55 After describing how Greenlee funded the first E-W contest with little help from his fellow owners, Wilson quoted Greenlee as “visioning a new and a better league” and concluded that “knowing Gus, I am optimistic about 1934.”

Looking backward, one can easily conclude that having another All-Star event was a sure thing. Nevertheless, it was not until early July of 1934 that an “[O]fficial announcement was made … that this ‘game of games’… will be staged again this year.”56 Amsterdam News columnist Romeo Dougherty asserted, “[T]he game this year has the approval of league officials and the club owners. … They realize that the East-West games, if continued, will perpetuate Negro baseball, and through Negro baseball will perpetuate the league. It’s the greatest bit of ‘good-will’ advertising ever engineered, and the games will be permanent.”57 Implied in Dougherty’s pronouncements is that many in the Negro League hierarchy were not so supportive of the E-W Game in the previous year. Negro League owners and officials now realized how crucial the E-W Game was to the successful promotion of Black baseball and the Negro Leagues.

For Greenlee, the general enthusiasm for staging a successful all-star contest in Black baseball by no means meant that criticism of his promotional methods, the competitive structure of the game, and especially the financial arrangements he and his partners Cole and Wilson were making would abate. Chief among the critics were Frank A. “Fay” Young and Cum Posey, but other negative voices also weighed in. From Young’s perspective, the selection process was flawed in 1933, such that star players like Newt Allen, Bullet Rogan, and Chet Brewer of the Kansas City Monarchs were not selected for the game even though they had gained substantial support in fan balloting.58 Young also questioned why no entity such as a “home for disabled Negro ballplayers or some worthwhile Negro charity” had yet to be designated as a beneficiary of the game.59 In addition, Young saw no purpose in having an East vs. West contest when there was no Eastern or Western circuit in the NNL. Young proposed that the Negro League game model itself after the American Association, which had the league’s leading club play an all-star team.60 Instead, what was being offered was “an East vs. West game in which the votes of the public are ignored … that is for the benefit of two promoters and their two dependent sports editors.61 While Young did not name any names, columnist Ed Harris, in writing a year-end review of the 1934 season, noted that Cum Posey had accused Gus Greenlee, Robert Coles, and Ed Bolden (owner of the Philadelphia Stars) of dominating the NNL, and specifically, that the balloting for the E-W contest was “dominated by these men,” an accusation that was confirmed in that both squads were largely populated by players from their three teams.62 Meanwhile, Lewis Dial wrote in the New York Age that a lot of “unsavory criticism” was being leveled at the 1934 E-W Game, and noted that Cum Posey had issued a press release announcing that his Homestead Grays would not participate in the game, as they had in 1933, because the voting was “a fake.”63 Dial then derided the sponsors of the 1933 game for failing to report on its financial outcome, while being “parsimonious with its tickets among sun-down scribes, but very generous to the white brethren.”64

John Clark had answers for all these criticisms. He editorialized that critics like Young and others, though “exercising a right as members of the fourth estate,” were criticizing “everything in general but nothing in particular” while the three game sponsors, Greenlee, Wilson, and Cole, were again bearing all expenses for the game and this time would “donate ten per cent of the gross receipts to the Negro National League.”65 Clark indicated that Greenlee and his partners were giving the public what it wanted and gambling their own money on the venture, while the critics were ”those who have a chronic inclination to oppose anything which they do not conceive or develop.”66 Clark detailed all the efforts of 1933 to reach out to newsmen, to advertise, and to operate openly to deliver a product worth watching by the general public. He also specified a careful approach, run by NNL personnel and endorsed by Commissioner Wilson, to make the 1934 game an even bigger success.67

Clark was not only one of those league personnel, but also an employee of Gus Greenlee, so his defense of Greenlee, Cole, and Wilson’s methods may have been less than objective. However, he was far from alone in his praise of the staging of the 1934 E-W game. Sportswriters Ches Washington, Romeo Dougherty, Dan Burley, and Nat Trammell all offered praise for the handling of the event, and much of it specifically lauded Greenlee’s efforts. Washington praised Greenlee, Wilson and Coles as “pioneers and advocates of a New Era – all men who were willing to put up their own money and take a chance” and who succeeded in drawing 25,000 fans to the 1934 East-West Game and a similar turnout to a four-team doubleheader at Yankee Stadium.68

Dougherty was even more fulsome in his praise of Greenlee, describing him as “one of the big men behind the staging of the East-West game. … Greenlee saw the possibilities last season after the first game … and decided if people are given the things they want in a big way they are only too glad to come out and patronize a real show or a real baseball game.”69 In another column devoted especially to depicting the 1934 Yankee Stadium doubleheader that Greenlee and his staff staged, Dougherty extolled Greenlee as “the man who could turn the attention of so many thousands of people towards a Negro ballgame … a man capable of Herculean efforts” and someone who “gathered unto himself a handful of men with hearts and hands determined. … In his systematic way of doing things, Mr. Greenlee chose and appointed each man of his promoting organization to a post to which he thought him best adapted.”70

Dan Burley was quoted extensively by Dougherty in a November 24, 1934, New York Amsterdam News column headlined, “What Negro Business Men Could Do if They Only Have Foresight.” According to Dougherty, Burley had a “style of voicing opinions this writer has held in the past, to say nothing of the present” and, in this case, Burley was in enthusiastic agreement with Dougherty about Greenlee’s successful role in staging the 1934 East-West Game.71 In a paragraph captioned “Greenlee Did It” (bold in original) Burley is quoted as follows:

“I have established as an undisputable fact that Gus Greenlee and others decided that an All-Star game could be arranged and played in a major league park and attract a crowd. This theory is established through published reports and the testimony of eye-witnesses at Chicago on September 26. …

“You know, of course, the results and the emphatic boost that colored baseball gained therefrom. Heroes, born under the hot sun of that sultry afternoon, bathed in the favor of the multitude. Such men as, as they so quaintly term them, Satchel Paige, Willie Wells, Willie Foster, and a fellow named Mule Suttles.”

Nat Trammell, who wrote for the short-lived Colored Baseball & Sports Monthly, which made its debut in September 1934 and called itself “The Only Publication of Its Kind in the World,”72 later wrote a piece on the 1934 game entitled “Baseball Classic – East vs. West.” He waxed eloquent as he described the game as “one of those classics where you must draw upon your aesthetic appreciation to fully digest its beauty.”73 Not only did Trammell credit Greenlee, Coles, and Wilson as “co-workers of this gigantic plan,” which he called “the greatest event that could be put over by anyone for the benefit of promoting interest in Colored baseball,” but he also implicitly gave the lion’s share of the credit for the game’s success to Greenlee, as he wrote that “(I)t is a source of joy to us to learn of the success of the East-West game. Mr. Greenlee is a real business man and a baseball promoter.”74

The 1934 East-West game was a pitcher’s duel, with the East prevailing, 1-0, when Cool Papa Bell walked, stole second, and was driven home on a bloop hit by Jud “Boojum” Wilson. Satchel Paige pitched four scoreless frames to close out the game and earned the win for the East, with Willie Foster giving up one run in three innings to take the loss.75 John Clark’s January 5, 1935, Pittsburgh Courier column reviewed the 1934 season and summed up Greenlee’s successful promotion of the 1934 game thusly:

“The game went on, and 20,000 people agreed that it was one of the greatest shows ever staged on a baseball diamond. …

“The National Association [NNL] benefitted to the extent of almost $1,000 from this game – a fact which proved to be a very good reply to critics of the classic. …

“It was [Greenlee’s] determination which inspired his organization to carry on the East-West promotion when critics speeded up their ammunition, and fired away at their targets.76

1935 – Greenlee and Posey Spar over E-W Game Profit Distribution

At the start of 1935, the NNL partially adopted Romeo Dougherty’s suggestion that it add two Eastern teams and form an Eastern and Western baseball association, with Gus Greenlee as president of the Eastern association, leading to a series at season’s end between the Eastern and Western champions.77 At the January 12, 1935, NNL meeting, the league voted to admit the Brooklyn Eagles and the New York Cubans and to give the Homestead Grays, previously an NNL associate member, a full league membership, which meant that eight teams now competed in the NNL; there were four teams in the East and four teams in the West, with Homestead and Pittsburgh considered to be Western outfits.78 Gus Greenlee continued as league president, but at the March 1935 league meeting, Commissioner Rollo Wilson was replaced by Ferdinand Q. Wilson.79

At the January 1935 meeting, it was reported that baseball officials “conceded 1934 to be a “best year” for colored baseball, and pointed to the East-West Game and the two exhibition doubleheaders in New York as highlights of the season.”80 President Greenlee, though, “reminded his colleagues that ‘in spite of the success of last year we have not arrived.’”81 The league passed five resolutions, including the following: “That the East-West game be repeated this year, with almost all profits going to the association’s treasury. (Last year only ten percent of net went to the association.)”82

This resolution, as well as John Clark’s assertion that same month that almost $1,000 had been realized by the league treasury from the 1934 E-W game, indicated that Clark had erred earlier when he said that 10 percent of gross receipts would be contributed to the league treasury from the 1934 game. Whether the Pittsburgh Courier’s 1941 report that the 1934 E-W Game took in $14,000 in receipts or its 1947 reporting of $20,000 in East-West receipts was accurate, the less than $1,000 contribution did not amount to 10 percent of gross receipts.83

In July 1935 the NNL announced that the league treasury would receive ”50 percent of the proceeds” from the 1935 E-W Game, with Greenlee, Cole, and Wilson “sacrificing their share for the purpose of setting up a fund to meet future emergencies affecting players and owners.” This, of course begs the question of what was happening to the other 50 percent that was not earmarked for the league treasury.

Cum Posey’s initial reaction to this declaration was very positive (for Posey, that is). He suggested that the pointed criticism he and Frank Young had leveled at Greenlee, Cole, and Wilson for benefiting themselves when they promoted the 1933 game was effective, leading to players and owners “working in harmony this season to put this game over in a ‘big way.’ Mr. Greenlee and Mr. Cole have sacrificed personal profit to strengthen the coffers of the league. …”84 Clearly, Posey was accepting the word of the three E-W sponsors that they would not directly profit from their promotional efforts.

The game itself was played on August 11, 1935, and resulted in an 11-8 slugfest won by the West squad in the 11th inning on a two-out, three-run homer by the powerful Mule Suttles before another turnout of 25,000 fans.85 Apparently, though, at least some of the players were disgruntled, as they were paid only $5 to participate in the game. An article by “Arbiter” in the August 24, 1935, Baltimore Afro-American reported that Greenlee had been willing to give the players $10 each, but other owners wanted to give them nothing. Commissioner Morton prevailed by suggesting $5 as a compromise, but Arbiter reported that players responded with “howls of protest” with one player throwing “his five dollars back on the table with a blasphemous opinion of the procedure.”86 The article went on to report that “the league did not promote the game, but was supposed to get 50 percent of the profits,” with one unnamed owner who was behind on his payroll to be “the chief beneficiary of the game, aside from the promoters, Greenlee, Cole and Wilson (emphasis added).”87

However, that wasn’t all the trouble that was brewing in the NNL. In an August 29, 1935, Philadelphia Tribune column headlined “Double, Double, Toil and Troubles Baseball Association Kettle Bubbles,” columnist Ed Harris avowed that the $5 payment to the players was “chicken feed considering the magnitude and the importance of the spectacle; questioned the validity of the player voting counts, noting that two players received the exact same number of votes; reported that Gus Greenlee was “reaching the limit of his financial resources” and gave as evidence for this assertion that the bus that was to take Crawfords players to the E-W Game had been attached for the nonpayment of a debt; and noted that “a goodly portion of the [E-W game revenues] was to go to the Association [NNL] treasury but at present such a settlement has not been made.”88

Not surprisingly, Greenlee felt compelled to respond to these charges in his own newspaper column. He identified himself as the “developer of the idea and principal promoter” of the East-West Game.89 He then wrote:

“I have never taken ‘all the profits.’ R.A. Cole, Tom T. Wilson shared in 1933 and 1934, and this year 50 per cent of the net receipts went to the league treasury. Having never promoted a game of this kind, few of the owners have any idea of the detail and expense involved. It only follows, however, that since they do not understand, they would oppose.”90

Greenlee addressed the players’ gripes about nominal payment for participation in the E-W Game and asserted that most of the players had not made a fuss. He made no mention of the alleged voting irregularities and did not directly address Harris’s claim that the Crawfords were in financial trouble. He did, however, mention his investment of substantial money, with significant losses, since 1932 in the Crawfords’ ballpark and operations as well as in league operations, and charged that “only a few of my associates” shared his vision that all the owners needed to make sacrifices to develop and maintain the viability of the NNL.91

One of the most prominent owners who did not share Greenlee’s vision was Cum Posey. Posey was so incensed that he wrote columns in 1935, 1936, and 1937 in which he vented his spleen at Greenlee and his associates for not living up to their promises regarding the distribution of the game’s proceeds. On November 30, 1935, “Cum Posey’s Pointed Paragraphs” ended thusly:

“The writer’s criticism of the financial settlement of the [1935 E-W] game rests on the resolution passed wherein the promoters and the league were each to receive half of the net receipts. Had this been lived up to, the league would have received all the money as it was the league’s money that ‘promoted’ the game.”92

Here, Posey did not name names, but his readership knew that this was directed especially at Gus Greenlee. Posey was much more direct and detailed in his criticisms nearly a year later. In his November 7, 1936, column “Posey’s Points,” he started out by saying, “[T]o think about the East-West game of 1935 is a headache.”93 He then proceeded to give the reader a headache as he stated that “[T]he plain facts about that game are: The league treasury furnished every cent for promotion. … The expenses were padded so strong that only $1,700.00 94 were cleared. If the league should rejoice because they got $850 out of a $14,000.00 promotion … then the league is only made up of two clubs and a secretary, as they are the only ones who profited.” Posey’s explanation was as clear as mud, but he did say directly that Robert Cole and Gus Greenlee “should have given the league all the money cleared.”95

Finally, Posey revisited – and revamped – his critique of Greenlee and his associates in a September 25, 1937, Pittsburgh Courier article headlined, “Posey Scores Gus on Setup for All-Star 9.”96 Now, Posey added more depth to his charges against Greenlee, stating that the night of the 1935 game, it was decided that the four Western clubs (Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Chicago American Giants, and Nashville/Columbus Elite Giants) would share in the East-West Game profits, leaving the four Eastern clubs to share in the coming Yankee Stadium doubleheader proceeds. Posey did not say if he had participated in this decision, but he stated that Robert Cole later announced that they “would deposit half of the net receipts to the league’s credit, the other half he and Mr. Greenlee decided to keep.”97

It is entirely possible that, at the time of the 1935 game, Greenlee, Cole, and Wilson had only intended to sacrifice their share of the 50 percent of the profits earmarked for the league. As the “money men” and promoters of the 1933 and 1934 contest, it seems likely that Greenlee, Cole, and Wilson thought they still deserved compensation for their pioneering efforts, even if they were not solely responsible for the promotion of the 1935 game. It is possible that Greenlee’s financial troubles led him to change his mind about sacrificing all compensation, but the league plainly stated that only half of the profits were to go into the league treasury, which left the other half for someone else. Posey’s 1937 broadside suggested that the three promoters had an obligation to share that half with the other Western teams, but they chose to keep it for themselves, and, according to Posey, “the only way any other club could get any of it would be through a judge’s order, and no other club did get it.”98 Posey’s charge is further supported by an article in the August 20, 1936, Philadelphia Tribune, which stated that “last year fifty per cent, was the league’s share, but owners were displeased because the remaining profits were not pro-rated among them.”99

Posey also asserted that Greenlee, Cole, and Wilson did not spend their own money on promotions for the 1935 E-W Game. Though Greenlee said in September 1935 that the other owners had no idea of the expense involved in promotion, that does not necessarily mean that he and his partners paid out of their own pockets; it could well have been a justification of their expense reports, since Posey in his 1936 article seems to have suggested that Greenlee and his cohort were exaggerating their expenses and thereby were pocketing money that should have been deemed profits. Arbiter’s 1935 article stated that the league did not promote the game, but he did not say that the league did not pay for those promotions. On the other hand, in an “exclusive interview” Greenlee gave to the Pittsburgh Courier in late August of 1936, he was quoted as follows: “Last year, the N.N. League [NNL] promoted the game, getting fifty-fifty [sic] per cent.”100

There is no doubt that Greenlee invested his own money in the 1933 and 1934 E-W Games and that he seemed to expect compensation for his investments, whether in the past only or continuing, as well as for his efforts and those of his sponsorship teams. Posey seemed to feel that he and other owners were not consulted about the decision-making process for disbursing profits; however, Greenlee felt that he had every right to make those decisions because of his role in developing and institutionalizing the E-W Game.

1936 – A Disgruntled Greenlee Relinquishes Control over the E-W Game, Then “Saves” It for Chicago.

In the aftermath of the 1935 game, Greenlee had his own grievances against the other league owners. He resented all the criticisms he faced about his role as “developer of the idea and principal promoter” of the East-West Game, as he felt that “[B]eneath the criticisms which are going the rounds is the vilest meanest kind of ingratitude.”101 Greenlee referenced “drastic moves now being planned” by other owners to take over league and East-West Game organization, saying that “Up to this time I have been a congenial fellow. But if these rumors are to develop into factual realities, you will see a fighting Greenlee, equipped with everything needed to win – and I will call the meeting, name the place and date.”102

In early May of 1936, Greenlee again wrote to air his grievances with the talk of the other “colored baseball men, especially members of the Negro National League, that I have wasted money on Satchell[sic] Paige.”103 Greenlee indicated that he had “no regrets for a single dollar I have spent on Satchell Paige. He is worth it. He is a part of my baseball gamble.”104 In discussing Paige, Greenlee reviewed the E-W games and Yankee Stadium doubleheaders he had principally staged in 1933 and 1934, saying that “[I]n all of these games I invested money. Advertising, park forfeits, transportation and the different items which go with promotions of this kind. … My friends in the East … can see no value in my pioneering work. …”105 Notably, Greenlee did not mention any 1935 expenditures that he undertook; rather, his complaints suggest he felt strongly that, having taken enormous monetary gambles and having succeeded in establishing the East-West and Yankee Stadium games, he deserved a separate share of the profits from these events in 1935 and perhaps going forward.

Greenlee felt that “after its [E-W Game] success had been assured, we were sorta shunted aside. …”106 He refused to serve on the NNL committee appointed to promote the 1936 East-West Game and, since he had already resigned the position of chairman of the NNL in January of 1936, it seemed that he was dramatically scaling back his participation in Negro League operations.107 As it turned out, Greenlee ended up being principally involved in the staging of the 1936 game, as the three appointed members of that committee – Newark Eagles co-owner Abe Manley, Roy Sparrow, and NNL Commissioner Ferdinand Morton – first decided to hold the East-West Game in New York in July and then, “[F]or some unexplained reason, the official committee made no attempt to promote the East-West game. …”108 Up to the plate stepped Greenlee, along with Tom Wilson, new Chicago American Giants owner H.G. Hall, and Kansas City Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson. Greenlee disagreed with “the action in deserting Chicago” and, when he discovered that the game would not be staged in New York, he “decided to go through with the game, because we wanted to keep faith with the public as well as revitalize the sport and perpetuate the game. And so, the game will be held in Chicago, where it has been held for the last six years.”109

On August 23, 1936, before 26,000 spectators at Comiskey Park, the East routed the West, 10-2, on a 14-hit barrage that included three hits and a stolen base by Cool Papa Bell.110 But the game, “featuring players from only four teams, lacked the all-star quality of previous years.“111 Naturally, those four teams were Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords, Wilson’s now-Washington Elite Giants, Hall’s Chicago American Giants, and Wilkinson’s Kansas City Monarchs. The Crawfords players were switched over to the East and played alongside the representatives of the Elite Giants, while the Chicago and Kansas City players represented two Western franchises that were independent of the NNL in 1936.112 Although the fourth annual E-W Game was still a success, five of its teams – the Homestead Grays, Philadelphia Stars, Newark Eagles, New York Cubans, and the New York Black Yankees, who became an NNL member for the season’s second half – were not a part of the contest and, according to league secretary John Clark, the league treasury received no money from the game.113

Clark provided explanations for the failure of the Manley-Sparrow-Morton triumvirate to carry out their plans for a New York E-W game, while also questioning the “motives behind the proposal” by Greenlee, et al. in taking over the contest.114 Manley, Sparrow, and Morton were going to give all the game’s profits to the league, but those three lacked the “finances, prestige and harmony” that Greenlee and his partners wielded.115 Nonetheless, Clark thought that the league still should have received a percentage of the game’s profits. Instead, Wilkinson received a fixed percentage, and apparently the other three promoters split the rest of the profits. In the final analysis, according to Clark, “[I]f the Negro National league is to continue it must have a treasury balance. This balance can only be piled up by earnings from games of this type.”116

1937 – Greenlee’s Participation Wanes

In 1937 Gus Greenlee returned to the presidency of the NNL, but his involvement in the E-W Game diminished, as other leaguewide and personal financial problems intervened. In March 1937 Greenlee traded the great Josh Gibson and star third baseman Judy Johnson to his bitter rival, Cum Posey’s Homestead Grays, in exchange for the considerably lesser talents of catcher Pepper Bassett and third baseman Henry Spearman. The deal was an exchange of talent at two positions, but was considerably augmented by the $2,500 sent to the Crawfords. It was a signal that Greenlee was in dire need of funds.117

Three major developments occurred in 1937, one of which had some promises but also challenges for the future viability of the NNL, while the other two were threats to its successful continuation. A rival league, the Negro American League, was founded in 1937 with Major R.R. Jackson named president, and eight teams from the Midwest joining. An incipient rivalry between the two leagues meant that there were ongoing disputes about teams from one league raiding those of the other, along with other periodic conflicts, but there was also a clear-cut delineation between East and West that could only enhance the competitiveness and prestige of the E-W Game. On the downside, the New York Cubans suspended operations in 1937 as team owner Alex Pompez left the country to avoid being arrested for his involvement in New York’s numbers rackets. Also, Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo successfully raided the Negro Leagues, signing a total of 18 players, mostly from the Cubans and the Crawfords, and including such luminaries as Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, and player-manager Martin Dihigo.118

Greenlee decreed that no players who left for the Dominican Republic would be allowed to play in the East-West Game even if they returned in time. He had concerns that new faces would therefore have to be introduced to the contest, but his concerns were alleviated when “20,000 frenzied fans paid to see the new faces take part in the East-West Game on August 8, and thereby demonstrated their confidence in Negro baseball and Greenlee’s promotions.”119 The game was won by the East, 7-2, with Buck Leonard driving in the first two runs on a home run in the second inning.120

Once again, though, Posey and Greenlee butted heads over the proceeds, with Newark Eagles co-owner Effa Manley playing a supporting role in the drama. According to Posey, Manley refused to allow her players to participate in the 1937 E-W Game unless NAL President Jackson made sure that all the NNL clubs got their share of the proceeds, which she secured and then gave to the other NNL clubs. Posey also charged that she uncovered an agreement between Jackson and Greenlee that guaranteed Greenlee 10 percent of the game’s receipts rather than “the 10 percent from the East which was legally his.”121 Of course, Greenlee had a different version of this encounter and claimed that Effa Manley “threatened to keep the ballplayers of all the clubs she represented out of the game unless all the monies were turned over to her. … Of course this was not done (ellipsis in original).”122 Furthermore, Greenlee stated that he asked all the clubs whether they wanted the E-W Game proceeds due them put into the league treasury or split among them and asserted that they all, “with the exception of Greenlee’s Crawfords, voted for the ‘split.’ This only goes to show that these owners do not have the good of the League at heart because the League owes plenty of bills right now.”123

Greenlee’s Final Classic

“West Beats East in Classic Thriller, 5 to 4

“Thirty thousand fans, bordering on hysteria, all did a ‘Susie Q’ Sunday afternoon at Comiskey Park in the home third of the sixth annual East versus West classic when Neil Robinson (Memphis Red Sox) slammed what should have been a single (or perhaps a double) to center field and Sam Bankhead (Pittsburgh Crawfords) let the ball go through him for a home run inside of the park – and away went the ball game.”124

The last East-West All-Star Game that directly involved Gus Greenlee was played on August 21, 1938. Greenlee had remained the NNL president, but he eventually resigned from his position and withdrew the Crawfords from the NNL in early 1939.125 To the end of his involvement, Greenlee would trumpet the success of the East-West All-Star classic and, even without his participation, the game continued to be played annually in Chicago for 22 more seasons.126 Also to the end of his involvement, Greenlee and his fellow owners were “haggling over disposition of profits.”127 The September 3, 1938, edition of the Chicago Defender reported that Greenlee, “who voted 10 per cent for originating the idea [of the E-W Game] … donated, presented or gave $600 to a Negro American League official. What was it for? Also for the good of baseball why isn’t a report published as to where all the money goes.”128

Perhaps Greenlee already knew that he would soon withdraw from the league at the time of the 1938 E-W Game, because he seemed to be giving valedictory speeches to the press about his role in its conception and its glorious future. In the August 6, 1938, Defender, Greenlee was quoted thusly: “… [T]he profit angle with me, Tom Wilson, and R.A. Cole, the men who first gambled with the idea, was secondary. What we set out to do, was put aside one day of glory for the players. … In presenting these players to the public, we replied to the demands which loyal fans had been making. … The manner in which the classic has been supported each year, bears me out in this claim.”129 Once more, in the September 3, 1938, Defender, he was quoted as follows: “‘As for the game itself, that has been a real success as was proven in the game held in Chicago last Sunday. Thirty thousand fans were present despite a Pittsburgh-Cubs doubleheader, which is proof of success. … The game in Chicago, Greenlee explained, will never be moved. ‘That contest is an institution now.’”130

Conclusion

Gus Greenlee made one final appearance on the scene of the East-West Game. In mid-1944 he applied for an associate membership for his revived Pittsburgh Crawfords. The league declined his application, although Cum Posey later said that the league approved Greenlee for an associate membership but not in Pittsburgh.131 Greenlee was not going to take this lying down, so he decided to sign away several players from each league by offering them much higher salaries than they were currently making, and also suggest that the players chosen for the East-West game go on strike if they were not offered more money.132 According to the Amsterdam News, “[T]he men with whom Greenlee was associated … are mostly against him and are fighting him tooth and nail to prevent his return to the baseball picture.”133

The players did not strike, as they got what Greenlee suggested they ask for, which was $200 apiece from NNL President Wilson and $100 plus expenses from NAL President J.B. Martin.134 Greenlee, who was “[a]lways known for his square-shooting with players and his willingness to help them,” said that “league club owners are getting ‘greasy with money.’” while “the ballplayers are still getting as low as $40 a week playing in many cases three games in one day.…”135

Gus Greenlee died in 1952 after a long illness. One of his most important legacies is his prominent role in developing and organizing the East-West All-Star Game. In his autobiography, I Was Right on Time, Buck O’Neil said:

“Let me tell you a little bit about the East-West game, because for a black ballplayer and for black baseball fans, that was something special. … That was the greatest idea Gus ever had, because it made black people feel involved in baseball like they’d never been before. While the big leagues left the choice of players up to the sportswriters, Gus left it up to the fans.”136

DORON “DUKE” GOLDMAN has been a SABR member for approximately half of its existence. A member of the Negro Leagues Committee, Duke has published several articles on the Negro Leagues and baseball integration, including SABR-McFarland award winners “The Double Victory Campaign and the Campaign to Integrate Baseball” and “1933-1962: The Business Meetings of Negro League Baseball.” Duke was also awarded the Robert Peterson Recognition Award for his Black Ball Journal articles and other SABR publications. A native of the Bronx now living in Northampton, Massachusetts, he calls a Yankees loss, Red Sox win, and Mets win a trifecta.

Notes

1 New York Amsterdam News, August 26, 1939.

2 The concept of the “big idea” is a well-known principle of advertising. Simply put, a groundbreaking creative slogan, execution, or principle can become a signature of a company’s brand, thereby aiding and enhancing its promotional efforts. See, e.g., David Ogilvy, Ogilvy on Advertising (New York: Vintage Books, 1985). The E-W Game was arguably, therefore, the key element of the identity of the Negro Leagues from its inception in 1933 onward.

3 Duke Goldman, “1933-1962: The Business Meetings of Negro League Baseball,” Baseball’s Business: The Winter Meetings Volume 2 1958-2016 (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2017), 393; Pittsburgh Courier, March 4, 1933. Greenlee was variously referred to as the chairman of the NNL and the NNL president.

4 John Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues (New York: Da Capo Press, rev. ed. 1992), xviii-xix.

5 Pittsburgh Courier, October 1, 1932.

6 Pittsburgh Courier, October 1, 1932.

7 Pittsburgh Courier, October 8, 1932.

8 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 29.

9 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (New York: Random House Value Publishing, Inc., 1970), 100.

10 Pittsburgh Courier, July 26, 1941.

11 Pittsburgh Courier, August 9, 1941.

12 Pittsburgh Courier, August 9, 1941.

13 Lester, 21.

14 Lester, 484 n. 1 (1933); Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 404 n. 34.

15 “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 15, 1942.

16 “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 15, 1942.

17 Alvin Moses, “Beating the Gun,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 9, 1939.

18 Moses.

19 Pittsburgh Courier, July 31, 1943.

20 Peterson’s seminal work lacked footnotes, so there is no direct evidence of the source material he used for delineating the role of Roy Sparrow in the E-W Game’s creation. It may also be possible that Posey’s 1942 account suggesting that in July 1933 Sparrow related a “pet idea” that Greenlee then turned into the E-W Game bolstered Peterson’s statement that Sparrow’s inspiration occurred prior to 1933.

21 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (New York: Walker & Company, updated ed. 2006), 73.

22 Pittsburgh Courier, July 29, 1933,

23 Pittsburgh Courier, August 5, 1933.

24 Pittsburgh Courier, August 5, 1933.

25 Pittsburgh Courier, July 29, 1933.

26 “Sez ‘Ches,’” Pittsburgh Courier, July 29, 1933.

27 Pittsburgh Courier, July 29, 1933.

28 Cleveland Call and Post, August 18, 1934.

29 Chicago Defender, June 17, 1933.

30 F.C. Lane, “An All-Star Baseball Game for a Greater Championship,” Baseball Magazine, July 1915, as quoted in Lew Freedman, The Day All the Stars Came Out (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc. 2010), 11.

31 Freedman, Stars, 12.

32 “Sez ‘Ches,’” Pittsburgh Courier, June 17, 1933.

33 “Sez ‘Ches,’” Pittsburgh Courier, June 17, 1933.

34 “Sez ‘Ches,’” Pittsburgh Courier, June 17, 1933.

35 Pittsburgh Courier, July 22, 1933. Posey placed 1933 Homestead Grays players like Vic Harris and Jimmy Binder and 1933 Pittsburgh Crawfords players like Josh Gibson and Oscar Charleston on the West squad. In the actual game, Harris, Gibson, Charleston, and other Crawfords and Grays players played for the East team.

36 Pittsburgh Courier, July 29, 1933.

37 Lanctot, 33-34.

38 “Sports Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 7, 1933.

39 “Sports Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 7, 1933

40 Philadelphia Tribune, March 11, 1944.

41 Pittsburgh Courier, August 11, 1951.

42 Lanctot, 23.

43 New York Amsterdam News, July 28, 1934.

44 New York Amsterdam News, July 28, 1934.

45 Pittsburgh Courier, August 1, 1936.

46 Pittsburgh Courier, July 26, 1941, July 26, 1947. In both 1941 and 1947, the Courier published a box listing attendance and receipts for each E-W Game to date. In 1947 the Courier reported the same $9,500 figure as receipts in 1933 but, for example, adjusted upward the amount of receipts for the 1934 game to $20,000 from a $14,000 figure reported in 1941.

47 Lanctot, 23. Note that Lanctot seems to be deducing this effort from John Clark’s July 28 Amsterdam News column, in which Clark stated that “(S)ports writers of 55 weeklies, 90 dailies were notified, and invited to comment and criticize.” Clark does not mention Sparrow’s name, but he was clearly heading the promotional activities for the first E-W Game. Black newspapers generally published weekly and White newspapers daily.

48 Baltimore Afro-American, September 9, 1939. Columnist Alvin Moses also reported that all the activity engendered by Sparrow and others he involved in his promotions led to “ninety-one press items all dealing with Roy Sparrow’s brainchild.”

49 “Fans Rally to East-West Baseball Poll,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 12, 1933.

50 Chicago Defender, August 5, 1933; Pittsburgh Courier, August 12, 1933.

51 Attendance was reported as 11,000 in the July 26, 1941, Pittsburgh Courier, 12,000 in Lanctot, 23, and 19,568 in Lester, 37, citing Kansas City Call, September 14, 1933. All three figures exceed the approximately 7,000 fans who turned out in Cleveland on July 23 to witness the “One Fine Day” doubleheader promoted by Dave Hawkins that featured the Crawfords and American Giants, from whom the majority of the East and West squad players were drawn.

52 Baltimore Afro-American, September 9, 1933 (ugly talk); Philadelphia Tribune, September 7, 1933 (receipts).

53 Philadelphia Tribune, September 7, 1933.

54 Pittsburgh Courier, September 30, 1933.

55 “Sports Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 7, 1933.

56 New York Amsterdam News, July 7, 1934.

57 New York Amsterdam News, July 7, 1934.

58 New York Amsterdam News, July 21, 1934. According to Lester, 37, 41, in 1933 Newt Allen got the most votes of any second baseman, while Chet Brewer ranked sixth in pitching votes and Bullet Rogan was seventh in the outfield. Right behind Rogan in eighth place was Sam Bankhead, who was one of only two starting players for the West squad who did not play for the Chicago American Giants – the other being shortstop Leroy Morney of the Cleveland Giants.

59 New York Amsterdam News, July 21, 1934.

60 Baltimore Afro-American, July 28, 1934.

61 Frank Young, New York Amsterdam News, July 21, 1934.

62 Philadelphia Tribune, September 13, 1934.

63 New York Age, August 4, 1934. Left fielder Vic Harris of Homestead started the 1933 game and pitcher George Britt relieved.

64 New York Age, August 4, 1934.

65 New York Amsterdam News, July 28, 1934.

66 New York Amsterdam News, July 28, 1934.

67 New York Amsterdam News, July 28, 1934.

68 “Sez Ches,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 15, 1934.

69 New York Amsterdam News, September 8, 1934.

70 New York Amsterdam News, September 9, 1934.

71 New York Amsterdam News, November 24, 1934.

72 Colored Baseball & Sports Monthly, Vol. 1, No. 1, September 1934. East-West Game file, Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York

73 Undated article, East-West Game file, Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York. The article has a handwritten notation underneath stating “Copied from Jimmie Crutchfield’s scrapbook.”

74 Undated article, East-West Game file, Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

75 Lester, 59, 61, citing Pittsburgh Courier, September 1, 1934.

76 Pittsburgh Courier, January 5, 1935.

77 New York Amsterdam News, October 20, 1934.

78 An associate member paid a smaller franchise fee than a full member and was included in the league schedule but not the final standings, and therefore could not play in any postseason games. See Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 391. In the 1935 E-W game, representatives of the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords played for the West team, whereas in the previous two games, they played on the East team. Lester, 37, 61, 78.

79 Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 401.

80 Baltimore Afro-American, January 19, 1935.

81 Baltimore Afro-American, January 19, 1935.

82 Baltimore Afro-American, January 19, 1935.

83 Pittsburgh Courier, January 5, 1935 (almost $1,000); Baltimore Afro-American, July 28, 1934 (gross receipts); Pittsburgh Courier, July 26, 1941 (1934 E-W receipts reported as $14,000); Pittsburgh Courier, July 26, 1941 (1934 E-W receipts reported as $20,000).

84 Cleveland Call and Post, July 25, 1935.

85 Lester, 79.

86 Baltimore Afro-American, August 24, 1935.

87 Baltimore Afro-American, August 24, 1935.

88 Philadelphia Tribune, August 29, 1935.

89 Chicago Defender, September 14, 1935.

90 Chicago Defender, September 14, 1935.

91 Chicago Defender, September 14, 1935.

92 “Cum Posey’s Pointed Paragraphs,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 30, 1935.

93 “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 7, 1936.

94 “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 7, 1936.

95 “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 7, 1936.

96 Pittsburgh Courier, September 25, 1937.

97 Pittsburgh Courier, September 25, 1937.

98 Pittsburgh Courier, September 25, 1937.

99 Philadelphia Tribune, August 20, 1936.

100 Pittsburgh Courier, August 1, 1936.

101 Chicago Defender, September 14, 1935.

102 Chicago Defender, September 14, 1935.

103 Chicago Defender, May 9, 1936.

104 Chicago Defender, May 9, 1936.

105 Chicago Defender, May 9, 1936.

106 Pittsburgh Courier, August 1, 1936

107 New York Amsterdam News, May 23, 1936 (Greenlee declines E-W committee membership); Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 402, citing Chicago Defender, January 18, 1936 (Greenlee resigning as chair of NNL)

108 Chicago Defender, November 7, 1936.

109 Pittsburgh Courier, August 1, 1936.

110 Lester, 91-92.

111 Lanctot, 54.

112 Lanctot, 54. (Western teams independent); Lester, 91 (Crawfords representing East).

113 Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 403 (1936 NNL teams); Chicago Defender, November 7, 1936 (no money to league treasury).

114 Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 403; Chicago Defender, November 7, 1936.

115 Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 403; Chicago Defender, November 7, 1936.

116 Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 403; Chicago Defender, November 7, 1936.

117 Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 404.

118 Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 402-404.

119 Pittsburgh Courier, August 21, 1937. Note that Lester, 105, reported an attendance of 25,000 for the 1937 contest.

120 Lester, 103, citing Pittsburgh Courier, August 14, 1937.

121 Pittsburgh Courier, September 25, 1937.

122 Pittsburgh Courier, September 18, 1937.

123 Pittsburgh Courier, September 18, 1937.

124 Lester, 112, citing Chicago Defender, August 27, 1938.

125 Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 407-408; Pittsburgh Courier, February 25, 1939.

126 In 1961, the E-W Game was finally played in Yankee Stadium, and the last E-W Game was played in Kansas City on August 26, 1962. See Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 446.

127 Lester, 112, citing Chicago Defender, August 6, 1938.

128 Chicago Defender, September 3, 1938.

129 Lester, 112, citing Chicago Defender, August 6, 1938.

130 Chicago Defender, September 3, 1938.

131 Goldman, Baseball’s Business, 422.

132 New York Amsterdam News, September 2, 1944.

133 New York Amsterdam News, September 2, 1944.

134 Lester, 225.

135 New York Amsterdam News, September 2, 1944.

136 Buck O’Neil, I Was Right on Time (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 121.