Judge Landis and baseball’s ban hammer

This article was published in the December 2019 issue of the SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee newsletter.

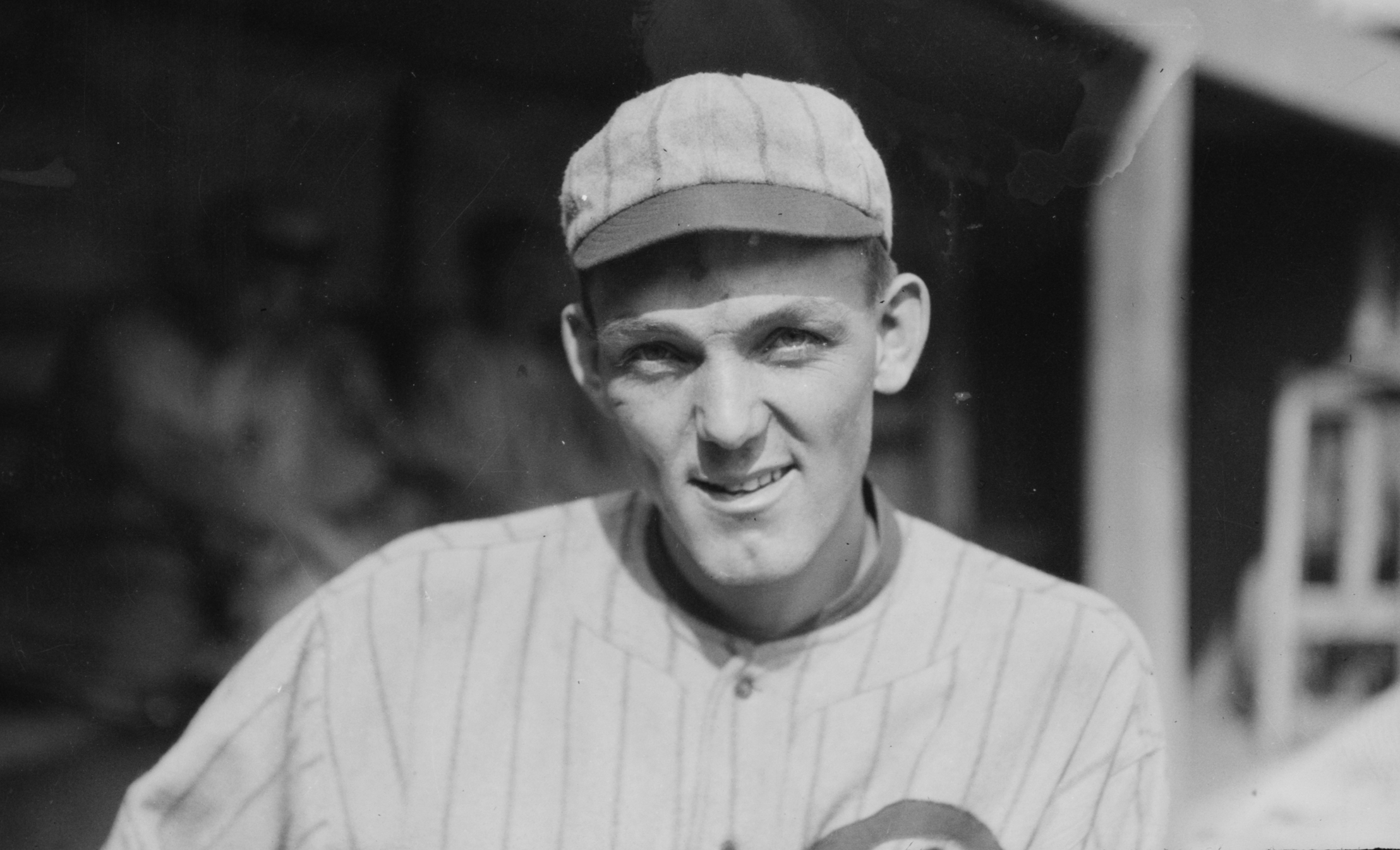

Buck Weaver was one of eight Chicago White Sox players who were banned for life following the 1919 World Series fixing scandal by baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. (Library of Congress, Bain Collection)

After the Black Sox players were exposed for fixing the 1919 World Series, they received punishment for their misdeeds from two different bodies.

The first punishment was from their own team, the Chicago White Sox. In late September 1920, team owner Charles Comiskey, confronted with grand jury testimony of the fix, invoked his powers under the standard American League player contract to indefinitely suspend his accused players.

Section 3 of that contract, which all the players signed, had the players vowing (in return for their salary) “to render for the club owner … his best services as a ball player.” Failure to render such “best services” was a “breach of contract” which allowed the club owner to either suspend the player or terminate his contract.1 Since the American League Constitution mandated the expulsion of any franchise that failed to terminate players who conspired to throw games, Comiskey had no choice but to suspend his players after they testified to the grand jury.2 The White Sox played the remainder of the 1920 season without these eight players.

The second punishment came immediately after the conclusion of their 1921 criminal trial in Chicago. Within 24 hours of the “not guilty” verdict, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis issued his now-famous edict: “Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ball game, no player that entertains proposals or promises to throw a game, no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever again play professional baseball.”3

Comiskey’s action has not attracted much historical comment or criticism, being subsumed by the more sensational trial and Landis’s edict that followed. This article will focus on Landis’s actions — specifically, his ban of White Sox third baseman Buck Weaver, the obvious target of the “does not promptly tell his club” clause above.

Author David Pietrusza is one of several historians who have accused Landis of rewriting Organized Baseball’s rules to cover the conduct of Weaver, who sat in on the conspiracy meetings but — as far as can be determined — accepted no money and played the 1919 World Series on the level. Landis’s decision to ban Weaver, Pietrusza wrote, “was to ex post facto place guilty knowledge of crooked play on the same level as the deed itself. Landis ratcheted baseball’s moral code up several notches, making it akin to West Point’s Code of Honor.”4

What was the legal, or even quasi-legal, justification for Landis’s edict? Regardless of the wisdom of the edict, regardless of whether the punishment was too great or too small, did Landis actually possess the authority in 1921 to ban Weaver’s 1919 conduct? And if so, did Weaver’s actions violate baseball’s 1919 rules?

Surprisingly little has been written about the Black Sox and the baseball rulebook. This article hopes to correct that omission.

The relevant 1919 rule, which notorious game-fixer Hal Chase was also charged with violating, was Section 40.

Crookedness and Its Penalties

Sec. 40. Any person who shall be proven guilty of offering, agreeing, conspiring or attempting to cause any game of ball to result otherwise than on its merits under the playing rules shall be forever disqualified by the President of the League from acting as umpire, manager, player, or in any other capacity in any game of ball participated in by a League Club. …”5

The “proven guilty” clause here refers not to any finding in a court of law, but rather to a finding of guilt by the National Commission, baseball’s ruling body. Baseball’s rules make no reference to court proceedings, and baseball’s uniform practice had been to determine guilt via its own inquiry.6 In the courtroom, the jury’s controversial decision to acquit the players rested on charges of legal conspiracy. But the jury could not address, let alone rule on, violations of baseball’s rules. By 1921, after Landis was hired as commissioner to replace the National Commission, he had the ultimate authority to make his own judgment of “proven guilty” in respect to Section 40.

From the naïve Shoeless Joe Jackson to fix instigator Chick Gandil, it is clear the Black Sox players’ actions violated Section 40 and that baseball’s rules allowed for a lifetime ban of them all. The players’ testimony showed they participated in meetings to play various World Series games “otherwise than on their merits” and accepted bribes from gamblers to do so.7

Section 40 gave the American League and National League presidents the power to “forever disqualify” (i.e., ban for life) any player who violated this rule. When Judge Landis took over as commissioner, he was given ill-defined but expansive powers over the game. Landis himself described his powers as “absolute.”8 At a minimum, he would possess the same powers that the “President of the League” possessed in 1919.9

Even if Landis’s edict is considered arbitrary, it must be remembered that the 1921 Major League Constitution, Art. 2, Sec. 3, had given him arbitrary powers. His edict also followed the relevant precedent of the 1919 Pacific Coast League game-fixing scandal, in which the PCL banished the indicted players even though the criminal charges against the players had been dismissed in court.10

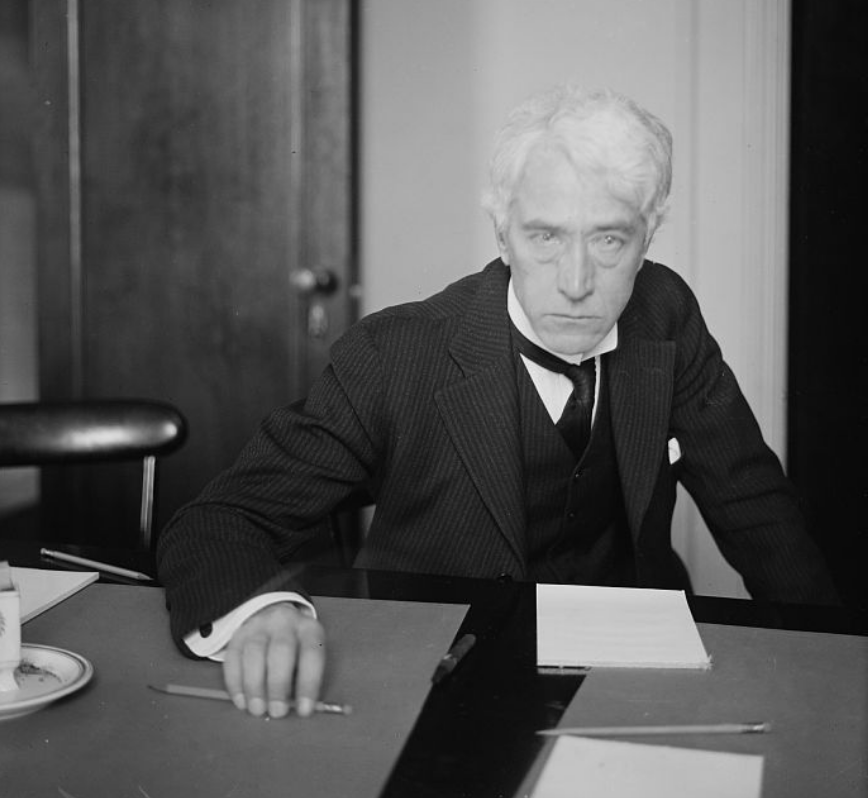

To punish Buck Weaver, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was not inventing a new rule ex post facto, but rather enforcing an existing rule in a manner consistent with legal principles. (Library of Congress)

It is the “Eighth Man Out,” Buck Weaver, whose punishment has attracted the most attention — and the most criticism. The facts of Weaver’s involvement in the scandal are in some dispute. For purposes of this article, I will posit that while he attended the conspiracy meetings with the other seven players, he ultimately decided to play on the up-and-up and did not accept any bribe money.

This scenario is about as favorable to Weaver’s case as can be. It ignores contemporary newspaper articles that claim Weaver threw games in 1920 and that report Weaver declined to join the fix only because the gamblers didn’t meet his price ($20,000 in advance).11

Judge Landis sensed the only way to restore fan respect for baseball, and to deter future misconduct, was to make an example of the players tainted by the Black Sox Scandal. That included Weaver, regardless of his play on the field. The final clause in Landis’s edict — “No player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers … and does not promptly tell his club about it” — pointedly referred to Weaver.

Landis’ edict banning Buck Weaver for life can be justified under Section 40 and relevant legal principles. The general legal definition of “conspiracy” is clear enough, and does not require actual completion of the illegal act:

“A conspiracy occurs where two or more people agree to commit an illegal act and take some step toward its completion. Conspiracy in an inchoate crime because it does not require that the illegal act actually have been completed.”12

Under Illinois law13 as it existed in 1919, a conspiracy in that state was complete upon the mere agreement to commit the unlawful act. No unlawful act was required. As explained by author Bill Lamb and others, one main legal problem with the Black Sox prosecution was that it wasn’t unlawful in Illinois to accept money for throwing a ballgame. The prosecution thus had to charge the players with conspiring to defraud the public instead.14

Under baseball’s rules, any conspiracy to throw a game could result in the conspirators being banned for life. The act of game-fixing is analogous to the “illegal object” of the conspiracy mentioned in the legal definition. While Illinois law didn’t make game-fixing illegal, baseball’s rules did specifically ban it. Thus the “conspiring” clause of Section 40 could validly be read, under legal principles, as making participation in the Black Sox conspiracy grounds to ban a player for life. And there is ample evidence that, initially at least, Weaver was an active participant in the fix.15

In some states, the law also provides a defense to a charge of conspiracy — withdrawal. Many Weaver defenders make what is essentially a claim that by playing honestly, he withdrew from the conspiracy. Legally, a defendant charged with conspiracy is allowed to raise the defense of withdrawal. In order to do so, a defendant must show 1) that he affirmatively communicated his withdrawal to his co-conspirators; 2) took some positive action to withdraw from the conspiracy; and 3) alternatively, that the conspirator must also alert the authorities.16 In a 2013 case, the US Supreme Court held that the burden of proof of withdrawal is on the defendant.17

It should again be emphasized that under baseball’s rules and Illinois law, Weaver could be banned based solely on his participation in the conspiracy meetings. Withdrawal would not be a defense to that action.

In addition, Judge Landis was not bound by the legal definitions of withdrawal, or to even consider withdrawal as a defense, under baseball’s rules. Even if the legal concept of withdrawal was applied here, Landis’s edict on Weaver still could be justified under the legal definitions of withdrawal.

Under the narrowest definition, Weaver didn’t clearly communicate his withdrawal to his co-conspirators. Indeed, the evidence suggests that going into Game One of the World Series, the other conspirators were unsure whether Weaver would play honestly or not. Joe Jackson, for one, testified that he thought Weaver “was in on the deal.”18 Under the more expansive definition, Weaver had an affirmative duty to disclose the conspiracy to the authorities — in this instance, White Sox team management — and his failure to notify means he could not use that defense.

If employees in any business conspire to defraud the business owner, common sense dictates that the business owner has the right to fire said employees. The actions of Charles Comiskey and Commissioner Landis in punishing the Black Sox appear to have exercised that common sense — and the move was approved in the court of public opinion.

In Buck Weaver’s case, Landis was not inventing a new rule ex post facto, but rather enforcing an existing rule in a manner consistent with legal principles. Along with the punishment of the players, a main justification for punishment is to deter future crimes, and in this sense, Landis’s edict has proven effective — baseball hasn’t seen any more World Series fixes.

Notes

1 In the words of the contract, “either to terminate this contract forthwith, by written notice, or to suspend the player, by written notice, without pay until the club owner is satisfied that the player is ready, able and willing to resume his services in the manner in this paragraph provided.” See, for example, the White Sox player contracts from 1917-20 signed by Eddie Cicotte, Red Faber, and Dickey Kerr held at the Chicago History Museum.

2 See Major League Agreement, Article 8, Sec. 4(d), January 12, 1921. The American League Constitution’s language on the expulsion of teams was similar to the National League Constitution, which can be viewed online at https://www.lib.umd.edu/univarchives/baseball .

3 Harold and Dorothy Seymour, Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press: 1971), 330.

4 David Pietrusza, Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, IN: Diamond Communications, 2001), 194. Others go so far as to proclaim Weaver’s “innocence.” See Greg Couch, “How Baseball Has Spent 96 Years Punishing An Innocent Man For The 1919 Black Sox Scandal,” VICE Sports, July 2, 2015, accessed online at https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/qkqyxp/how-baseball-has-spent-96-years-punishing-an-innocent-man-for-the-1919-black-sox-scandal .

5 See the Atlanta Constitution, February 6, 1919, for the text of this section and a discussion of the Chase case. Section 40 can also be found in Reach’s Official 1919 American League Base Ball Guide (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Co., 1919), 148, accessed online at https://archive.org/details/reachofficialame19181phil/page/148 .

6 Cf. the 1877 case of the four Louisville Grays players who were banned from baseball by the National League after a league investigation. Section 40 encompassed actions that were not illegal per se, but rather against the best interests of baseball, and thus a Section 40 ban didn’t depend on any court finding of criminal guilt. Legal concepts such as “jury nullification,” which Black Sox author Bill Lamb argues is the reason why the Black Sox were acquitted, had no bearing on any determination under baseball’s rules. In practice, however, baseball officials understood their rulings would be more accepted by the public if the rulings followed legal principles.

7 From the evidence it is unclear how many, if any, of the Black Sox also violated baseball’s rules against betting on games. It was charged that Lefty Williams (or his wife) wagered on the 1919 Series (a charge Williams denied), while author Eliot Asinof alleged that Chick Gandil also placed bets on the Series.

8 Pietrusza, Judge and Jury, 174.

9 American League president Ban Johnson also would have had the authority to issue the same order Landis did.

10 Larry Gerlach, “The Bad News Bees: Salt Lake City and the 1919 Pacific Coast League Scandal.” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2012).

11 On the 1920 allegations, see Bruce Allardice, ” ‘Playing Rotten, It Ain’t That Hard to Do’: How the Black Sox Threw the 1920 Pennant.” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2016. On Weaver and 1919, see the Pittsburgh Post, October 1, 1920.

13 The criminal case was tried in an Illinois court under state law. However, the initial conspiracy meeting was held in New York, and other parts of the conspiracy (the game-throwing) occurred in Ohio. In theory, conspiracy charges could have been brought in any of these states. In any event, Commissioner Landis was not bound by the laws of any of these states.

14 See William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013), 101-102, for a discussion of the conspiracy laws that applied to the Black Sox 1921 prosecution.

15 Four different fix insiders — Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, Lefty Williams, and Bill Burns — testified under oath that Weaver was present at the pre-World Series meetings.

16 See https://www.justia.com/criminal/defenses/abandonment/ Cf. http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1634&context=facpubs

17 Smith v. U.S., 568 US 106, 133 S Ct 714, 184 L Ed 2d 570 (2013). Smith held that withdrawing from a conspiracy does not negate that a defendant participated in a conspiracy; it merely excuses post-withdrawal conduct from liability. Smith reminds conspirators that, in order to claim withdrawal, they must, at the least, communicate their decision to withdraw to their co-conspirators. “Passive non-participation in the continuing scheme is not enough to sever the meeting of minds that constitutes the conspiracy.”

18 Charles Fountain, The Betrayal: The 1919 World Series and the Birth of Modern Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 80; Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 53.