Kings of the Hill: The Story of the Pittsburgh Crawfords

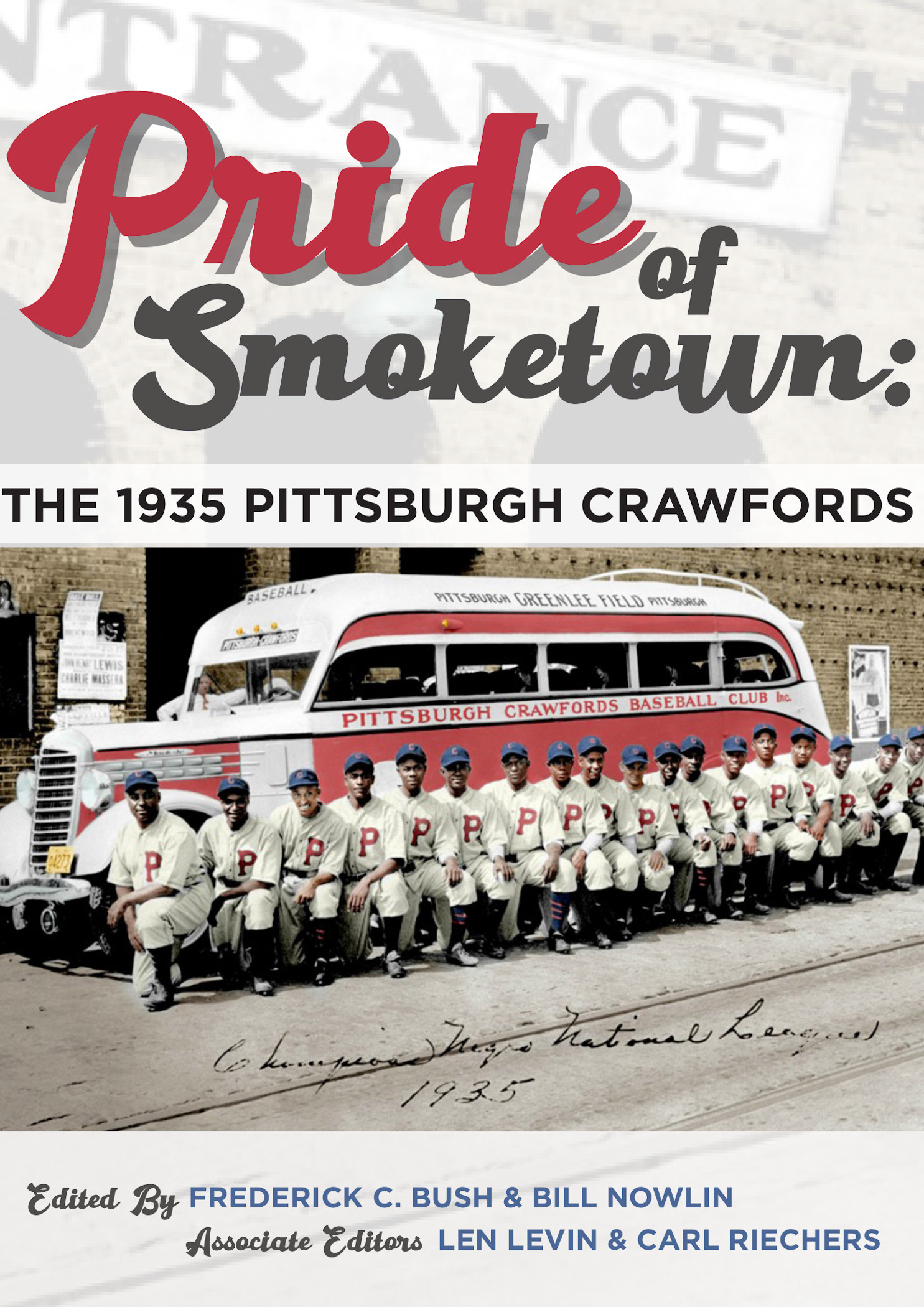

This article appears in SABR’s “Pride of Smoketown: The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords” (2020), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

The Pittsburgh Crawfords franchise, one of the most famous in the history of black baseball, was started in 1926 by a group of youths connected to one of Pittsburgh’s neighborhood recreation clubs. For five years the Crawford Giants, as they were first known, labored in relative obscurity as an amateur or semipro outfit. Things changed dramatically when a wealthy local gangster named William A. “Gus” Greenlee decided the team provided the perfect vehicle for burnishing his reputation, laundering a little money, and having a lot of fun.1

The Pittsburgh Crawfords franchise, one of the most famous in the history of black baseball, was started in 1926 by a group of youths connected to one of Pittsburgh’s neighborhood recreation clubs. For five years the Crawford Giants, as they were first known, labored in relative obscurity as an amateur or semipro outfit. Things changed dramatically when a wealthy local gangster named William A. “Gus” Greenlee decided the team provided the perfect vehicle for burnishing his reputation, laundering a little money, and having a lot of fun.1

Greenlee had become involved with the Crawfords around the time of the team’s founding by donating money for the boys’ uniforms. Over the next few years he focused less on baseball than on building his numbers empire. In that effort he was spectacularly successful. Building on lessons learned from running liquor as a taxi driver in the years following World War I, and leveraging the opportunities offered by the speakeasy he owned, by late 1931 Greenlee had become both Pittsburgh’s undisputed Numbers King and one of its most charismatic and recognizable figures. Alternately charming or ruthless, as circumstances warranted, Greenlee flashed as his calling cards expensive suits (silk preferred), expensive cars (usually a Lincoln convertible), and beautiful women (obtained and discarded with equal ease). The illegal numbers lottery made such indulgences financially feasible. Greenlee probably raked in between $20,000 and $25,000 per day during the height of his seemingly Depression-proof business in the mid-1930s.2

Yet, although the numbers lottery was profitable, the cash it generated was problematic. That seems to be one of the reasons Greenlee decided in 1931 to increase his investment in the Crawfords significantly. Since its formation in 1926, the Craws had gradually separated themselves from Pittsburgh’s other black sandlot teams. The team’s collection of impressive talent had included outfielder Jimmie Crutchfield, pitcher Sam Streeter, and, most notably, a catcher named Josh Gibson, who began playing with the team in 1928 as a side gig to his work in the steel mills. Gibson had been plucked away from the Crawfords by the Homestead Grays – then Pittsburgh’s highest-level and only fully professional Negro Leagues team – in 1930. In June 1931, after Greenlee had decided to assert team control, the Crawfords replaced him with a catcher from Cleveland named Bill Perkins. Perkins was joined by an intriguing pitcher by the name of Satchell (yes, spelled at first with two l’s) Paige.3

Earlier during that 1931 season Streeter and the Craws had been crushed by the Homestead Grays, 9-0. But when the Crawfords met the Grays in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, on August 1, things were different. The Grays had just clawed back from a five-run deficit to tie the score at seven when a tall, long-limbed, rail-thin young man strolled slowly to the mound to relieve Craws starter Harry Kincannon. Paige’s fastball was like nothing the Grays, or anyone, had ever seen. He held Posey’s dangerous lineup at bay, and the Craws won, 10-7.4 It was a proof-of-concept game for Greenlee and his rising club.

The next year, 1932, Greenlee began to push in all his chips. First, he finished construction on the Crawfords’ very own ballpark in Pittsburgh’s Hill district, an area called home by tens of thousands of black Pittsburghers. Despite its lack of a covered grandstand – an omission that would soon be lamented – the community marveled at the new red-brick, $100,000 Greenlee Field, which seated 7,500 and included showers and dressing rooms for both the home and visiting teams – an important amenity, given that Negro Leagues teams were not allowed to use those facilities at the Pirates’ Forbes Field, their usual venue for big games. That Greenlee had managed to build his new ballpark in the midst of the Great Depression was widely considered an incredible feat, and it increased his prestige substantially.

Second, Greenlee succeeded in hiring as the Crawfords’ new manager the man who was considered the greatest all-around player in Negro Leagues history and still was considered the black game’s best gate attraction: Oscar Charleston, who had burst onto the scene in 1915; had carved out a legendary career with the Indianapolis ABCs, Harrisburg Giants, and Hilldale Daisies (among other clubs); and, for the previous two years had played first base for the Grays.5 This was a coup, as Charleston was not only popular but was well-connected and widely respected. Within days of his hiring, Charleston had obtained commitments from Paige, Streeter, Kincannon, Roy Williams, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Bobby Williams, and Jimmie Crutchfield to join the club (Williams and Radcliffe had been Oscar’s teammates on the 1931 Grays). A short time later, Josh Gibson, Rev Cannady (perhaps the best hitter in black baseball in 1931), and Rap Dixon signed on as well.

Third, Greenlee, never one to take half-measures, invested heavily not just in facilities and players, but in amenities as well. The team now traveled in a new, comparatively luxurious Mack bus with the words “Pittsburgh Crawfords Baseball Team” emblazoned along its side. The team’s equipment was first rate, as Al Monroe of the Chicago Defender once noted. “[I]n comparison with many another club [Greenlee’s equipment] rates with the major leagues. Carrying no more than fifteen men Gus has supplied his club with more than two bats per player and then, they tell me, an order was placed for a dozen more. Now, if you don’t think that an exception, then stop and have a talk with some of the players on other teams,” wrote Monroe.6 Furthermore, as of 1933, team members could hang out with pride at their owner’s new Crawford Grill. With its diverse clientele and celebrity acts, the Grill quickly became the most popular spot on the Hill district’s main thoroughfare, Wylie Avenue. Virtually every Negro Leaguer who came through the city hung out there. The Depression made life difficult for everyone, not least the nation’s African-Americans, but at the Grill, as on the diamond, it was damn good to be a Crawford.

Fourth and finally, in 1933 Greenlee rebooted the Negro National League and cast himself in the Rube Foster founding-father role. The new NNL enjoyed more than its share of controversies and financial challenges, but for 16 years Greenlee’s league provided a measure of stability and structure for players and fans. From 1933 through 1936, it was the only major black baseball league in existence.

The history of the Crawfords can be neatly divided into two phases: the major period of 1932-36, marked by black baseball championships, legendary contests, and the rise of Paige and Gibson, especially, to superstardom; and the minor period of 1937-40, marked by financial struggle, decay, and Oscar Charleston’s poignant attempt to keep the club afloat. (We will ignore here the very brief period, in 1945-46, during which the Crawfords were revived by Greenlee as part of the new and short-lived United States League.)

The 1932 version of the Crawfords, sometimes said to be one of the finest teams ever assembled, was in truth something of a disappointment. Although they featured five future Hall of Famers in Paige, Gibson, Charleston, Judy Johnson, and Jud Wilson (the latter two joined the team in midseason), and although the supporting cast included above-average to excellent players in Dixon, Cannady, and Ted Page, the 1932 Crawfords somehow lost their season series with the Homestead Grays. At the time, the team was reported as having put together an overall record of 99-36, but as usual that record included games against scores of semipro and minor-league-level teams. As best we can now tell, the Craws finished 32-26-1 against top black competition.7

That was an entirely unexpected outcome. But any expressions of disappointment were largely muted thanks to the development of Paige and Gibson. By midsummer 1932, Charleston, who was at first the team’s biggest star, had been forced to share the spotlight with Satchel and Josh. In an eight-game late-June series versus the Grays, Paige and Gibson were the Craws most praised by the Pittsburgh press, and, on July 16 at Greenlee Field, Paige won more esteem by hurling a no-hitter against the Black Yankees. By the end of the season, it was the amazingly powerful Gibson, rather than Charleston, who was being called “the black Babe Ruth.” The 1932 Crawfords kept careful hitting records, and Gibson’s achievement, in just 490 at-bats, of 114 runs, 186 hits, 45 doubles, 16 triples, 34 homers, a .380 batting average, a .417 on-base percentage, and a .745 slugging percentage heralded the arrival of the black game’s newest star. Or rather, one of them, for Paige managed the stunning feat (for the time) of striking out more than a man per inning on his way to an ERA of 2.46.8

In 1933 the speedy James “Cool Papa” Bell replaced Rap Dixon in center field. With Bell leading off, Page hitting second, Charleston batting third, Gibson manning the cleanup spot, and Johnson protecting him in the five hole, four Hall of Famers filled the 1933 lineup’s top five slots – and the one non-Hall of Famer, Page, would that year post a 138 OPS+ against top competition. (The 33-year-old Johnson, in truth, was slipping; he would post a mere 72 OPS+ for the year.) Led by Charleston, a super-fast outfield, the game’s hardest hitter in Gibson, and its hardest-throwing pitcher in Paige, the Crawfords rolled through the season’s first two months like the elite club they were. As of June 24, they reportedly led the league with an 18-7 record, due in large part to Oscar’s .450 batting average in 60 official at-bats. Bell was hitting .379, Gibson .378, and Perkins .344. Nevertheless, the Chicago American Giants – which featured four future Hall of Famers of their own in Turkey Stearnes, Mule Suttles, Willie Wells, and Willie Foster – claimed the new NNL’s first-half pennant.

After the first East-West All-Star Game – another successful Greenlee innovation – was played in Chicago’s Comiskey Park on July 6, 1933, the Crawfords picked up the intensity. On September 30 and October 1, the club played the Nashville Elite Giants in a three-game series that would decide the second-half pennant, with the winner to play the American Giants for the league championship. The Crawfords needed to win only one of these contests. After losing the first at Greenlee Field, Charleston sent Paige to the mound for the first game of the next day’s doubleheader. The Craws took a 4-2 lead into the bottom of the ninth, but the Elites managed to scratch across the tying runs off Paige before Leroy Matlock relieved him and ended the threat. Finally, in the top of the 12th, Cool Papa Bell hit a screaming liner to deep center and flew around the bases for an inside-the-park home run. Matlock closed the door in the bottom of the frame.

And then … there was no championship series after all – or at least none that was completed.9 The Craws and American Giants met in Cleveland on October 8, 1933, and played to a 7-7 tie. But for the series’ second game, in Wheeling, West Virginia, only seven American Giants players showed up. The game was played anyway – and predictably won by the Crawfords. That was enough for the remaining American Giants, who refused to go on to Pittsburgh for the series’ scheduled third game. Thus was the 1933 NNL championship forfeited to the Crawfords in most anticlimactic fashion.

With Vic Harris supplanting Ted Page in the two hole, the 1934 Crawfords boasted an even better first four in their lineup – Bell, Harris, Charleston, Gibson – than they had in 1933. The pitching depth was strong, too, with Paige leading a staff that still featured the underrated Leroy Matlock, Sam Streeter, Harry Kincannon, and Bert Hunter. By the end of the year, Paige separated himself from this pack forever; however, in early 1934, it wasn’t yet clear that he was the staff’s sure ace.

Paige’s importance to the club didn’t stop Greenlee from loaning him to the House of David to play in the Denver Post baseball tournament in the middle of the season.10 Thanks to Paige’s absence and injuries to Charleston and Judy Johnson, the Crawfords again finished behind the American Giants for the NNL’s first-half flag. Getting Paige back for the second-half chase was not enough to lift the Crawfords to that flag, either, which was taken by the Philadelphia Stars. The Craws’ 47-27-3 total record in 1934 was the second-best in the league, but it was not good enough in either half to put them in line for a championship. The months of September and October nevertheless contained two of the most memorable series of games the Pittsburgh Crawfords ever played.

The first consisted of a string of doubleheaders in which Paige continued to blossom into a full-blown superstar.11 On Sunday, September 9, the Crawfords participated in a four-team doubleheader at Yankee Stadium. Battling the Philadelphia Stars in the second game of the day, in front of a raucous crowd estimated to be between 25,000 and 30,000, the Craws were no-hit by Slim Jones for six innings before Oscar Charleston broke through with a single in the seventh. They failed to score, but with Paige holding the Stars to a single run, the Crawfords tied the game in the eighth. Then, in the bottom of the ninth, the Stars loaded the bases against Satchel with one out. Paige struck out the next two men he faced – his 11th and 12th strikeout victims of the day – to preserve the tie before the game was called because of darkness. Bill “Bojangles” Robinson memorialized the duel by giving both Paige and Jones travel bags embossed with the words “the greatest game ever played.”12

The Crawfords returned to Yankee Stadium on Sunday, September 30. This time 35,000 fans showed up to watch Paige again battle Slim Jones and the Stars. Once again, Paige got the best of Jones, fanning 18 Stars to lead the Crawfords to a 3-1 victory. There was no doubt who the Crawfords’ – and black baseball’s – biggest star was now. Satchel Paige had come into his own.

Never one to allow himself to be saddled by the burden of team expectations, Paige decided in spring 1935 to forsake the Crawfords and the two-year contract he had signed with Greenlee in favor of Bismarck, North Dakota, where a white auto dealer named Neil Churchill, who had lured Paige to the high plains in 1933, had once again offered him a handsome amount to pitch for his semipro club. With Vic Harris and Ted Page also departing the Craws, Charleston a year older at 38, and a fast-declining Judy Johnson now 35, the 1935 club did not project to be nearly as powerful as previous year’s squads. Expectations, on the outside, were for the team to be good, but no longer the juggernaut it once was.

Led by Josh Gibson, who was still just 23 (and who had allegedly hit 69 home runs in 1934), and pitchers Bertrum Hunter and Harry Kincannon, the team got off to a fast start. It was greatly aided when, in June, another 23-year-old, Andrew “Pat” Patterson, came on board to take over second base. After the Crawfords beat the Homestead Grays in both ends of a July 4 doubleheader in Pittsburgh, before a crowd of 12,000, their 24-6 record was good enough to claim the first-half pennant.

Things didn’t go as well in the second half. The team surely missed Paige, although Matlock was brilliant in his stead, posting a 1.52 ERA, and the rest of the staff was solid. But the main problem was the degradation of Charleston’s game. Far from serving as a powerful complement to the young Gibson, Charleston hit just .271 and slugged only .387 over the year, offensive numbers that lagged far behind those posted by Gibson, Bell, Patterson, and outfielder Sam Bankhead. As a result, the second-half NNL flag was taken by the New York Cubans, who were led by Cubans Alejandro Oms and Martin Dihigo, the latter of whom also managed the squad. The Cubans’ second-half victory set up a Crawfords-Cubans NNL championship series.

In their level of organization, publicity, and generated interest, black-baseball World Series never managed to live up to those staged by the majors. As the 1933 championship debacle demonstrates, the leagues themselves simply didn’t command enough respect for pennants to be viewed with awe, and the owners never stuck with one model long enough for fans to become invested. The 1935 series was no exception to the rule. The seven-game series started at New York’s Dyckman Oval on Friday, September 13.13 It bounced to 44th and Parkside in Philadelphia the next day, then back to Dyckman Oval on Sunday the 15th, before finally getting to the Crawfords’ home city for Games Four and Five on the 17th and 18th. The schedule was so confusing that three of the four umpires went to the wrong ballpark for Game Two, and the crowds were of only middling size. The players, nevertheless, were fully engaged. Legitimate blackball World Series were rare enough that for them to win one really meant something. Plus, there was some real money on the line.

The Cubans landed the series’ first punches, winning the first two games, 6-2 and 4-0. Matlock came back to blank the Cubans 3-0 in the third contest, in which Charleston homered, but he was too gassed to stave off Dihigo in Game Four, losing 6-1 at Greenlee Field. Down three to one in the series, the Crawfords were on the verge of elimination.

The next day, Roosevelt Davis and Cool Papa Bell willed the Crawfords to victory. Davis pitched a brilliant complete game but unfortunately gave up a tying pinch-hit home run in the top of the ninth. Bell then came to the rescue. In the bottom of the inning, his aggressive baserunning led to a wild throw to third. He scampered home to give the Craws a 3-2 victory, narrowing their series deficit to the same margin.

The following night, play resumed in Philadelphia. Charleston started Bert Hunter, but the best he, Bill Harvey, and Matlock could do was to hold the Cubans to six runs. The Crawfords found themselves down 6-3 as the game headed into the bottom of the ninth. Dihigo then made a fateful mistake. Instead of letting his splendid rookie pitcher Schoolboy Johnny Taylor try to close things out, he took the mound himself. It was a defensible decision, given that Dihigo had that year posted a virtually identical ERA to Taylor’s (2.70 and 2.78, respectively). But with Taylor pitching well, it was probably unnecessary. Dihigo allowed light-hitting shortstop Chester Williams to reach base. Then Gibson got aboard. There were two outs, and the Craws were still down three, when Oscar Charleston stepped into the left-side batter’s box.

The field at 44th and Parkside had been the site of some of Oscar’s most memorable moments. But he was nearly 39 now, overweight, and had just struggled through his worst offensive season. Dihigo, at 30, was in his prime. He still had a three-run lead. And all he needed was one out. The odds against Charleston winning this battle were so long that Cubans owner Alex Pompez and team business manager Frank Forbes were already counting out the winners’ share of the money in the clubhouse. As they counted, they heard the crowd erupt. Charleston had timed a Dihigo offering and sent it sailing over the center-field wall for a game-tying three-run blast. Forbes, disgusted, threw a bundle of $500 across the room.14 Soon thereafter, the Crawfords’ Pat Patterson doubled, and, when pinch-hitter Judy Johnson knocked him in with a single, the Craws had completed one of the most dramatic big-game comebacks the Negro Leagues had ever seen.

The next night, September 20, the Crawfords were nursing a 5-4 lead on the same diamond in the top of the eighth when Josh and Oscar struck again, hitting back-to-back home runs. Dihigo made an error that allowed another run to score, and the Craws held off a furious Cubans rally in the bottom of the ninth to complete a thrilling 8-7 win. This time there would be no doubt about it. The Crawfords – sans Satchel Paige – were the 1935 NNL champs.

Some days later, when the Craws returned to Pittsburgh, Greenlee feted them with a victory feast at the Crawford Grill. Pittsburgh Steelers owner Art Rooney, Bojangles Robinson, and the singing Mills Brothers, who were such big fans of the team that they had their own Craws uniforms and sometimes worked out with the club before games, were all there.15 It was a huge, happy affair, and Judy Johnson thought Gus took all the more satisfaction in the championship because it had been achieved without Satchel.16 That was probably true of not just Greenlee, but everyone.

It was nevertheless a pleasant surprise when, on April 21, 1936, Paige reported to the Crawfords’ spring-training camp in Pittsburgh. Having pitched in the California Winter League over the winter, Satchel was already in midseason form, as he demonstrated convincingly enough when he threw a no-hitter in an exhibition game vs. the Akron Grays on May 3. By this time, Paige was transcendently popular, and his presence redounded to everyone’s benefit on the field and at the gate, even when one accounted for his exasperating habits – like failing to show up for games, for example. As Pittsburgh Courier columnist Chester Washington wrote on May 9, throughout the East black baseball fans were now “Crawford-crazy,” and the return of Paige, “a natural showman … as spectacular as a circus and as colorful as a rainbow,” would only make the team more popular.17

A balanced Washington Elite Giants club edged the Crawfords and the Philadelphia Stars for the NNL’s first-half flag in 1936, in part because – outside of Gibson and first baseman Johnny Washington (whom Charleston had allowed to replace himself as the usual starter at the position) – none of the Craws had a particularly good offensive season. Judy Johnson was now a shell of himself, and new acquisition Dick Seay, although a wizard at second base, barely hit his weight. But the Crawfords started the second half hot and never took their foot off the gas. In late July they were 8-2, and as of mid-August they remained in first with a 13-6 record; ultimately, they would win the flag with a 19-8 mark.18 By that point, however, the NNL was fraying at the seams, and a championship had come to mean little to both the players and the fans. On September 21 the Elite Giants won the first game of the NNL title series in Philadelphia, but numerous Crawfords stars were absent.19 They were off barnstorming in the West, figuring that the money they could earn on the road was worth more than the crown of a league that commanded little prestige. No other series games were played; as a result, the NNL had no official champion in 1936. Reconstructed records show that the Crawfords, at 48-33-2, had the league’s best record against top competition.

With Paige, Gibson, and several other players still in their primes, the Crawfords appeared poised to remain one of black baseball’s most dominant teams for years to come. But in spring 1937 everything changed.

First, Greenlee’s luck ran out. He reportedly suffered a big hit in the numbers game and suddenly was short of cash.20 When Gibson held out for more money, the Crawfords traded him (and the broken-down Judy Johnson, who immediately retired) to the Grays for catcher Pepper Bassett (and, perhaps most importantly, $2,500 in cash). Greenlee may have had little choice, but this must nevertheless be considered of baseball’s most disastrous trades. Think Brock-for-Broglio, but much, much worse.

Next, Greenlee encountered competition from a most unlikely source: a tinpot tyrant from the Caribbean named Rafael Trujillo.

The Crawfords were training in New Orleans in April when a Dominican man named Dr. José Enrique Aybar, along with a few associates, cornered Satchel Paige on the street. Aybar was on a recruiting trip.21 His task was to find the best players possible for the Dragones de Ciudad Trujillo, a baseball team representing the Dominican Republic’s capital city, recently renamed for the megalomaniacal dictator who had taken control of the nation a few years earlier. Trujillo had made ample funds available to Aybar – not so ample that he could lure white players away from the major leagues, but plenty to turn the head of a Negro Leaguer like Paige. Once Aybar, brandishing a pistol (in Paige’s telling), had Satchel’s attention, he offered the astounding sum of $30,000 for Paige and eight of his teammates to come play in the island nation. From that amount Satchel could take whatever he thought was his fair share. Much stronger men than Satch would have been unable to resist such an offer. Paige accepted and began to recruit his fellow Crawfords.

News that Paige and others had jumped or were thinking about jumping had already reached Greenlee and Charleston when, on or about Friday, May 8, two Trujillo men showed up in Pittsburgh looking for yet more players. Ernest “Spoon” Carter was among those who agreed to go. But the next day he had second thoughts and decided to confer with his wife and Charleston. Charleston reported the conversation to Greenlee, who, after fruitlessly threatening legal action, pivoted to plan B, which was to try to work out an arrangement with the men representing Trujillo. He may have wanted to sell a couple of players in exchange for a deal that would prevent any further tampering. Indeed, he reached out to his fellow owners with a proposal that would require the Dominicans to deal directly with league headquarters if they wished to acquire anyone. Alas, seeing that the Crawfords were the only team that was really going to be decimated by the raids, Greenlee’s fellow owners reacted coolly to his idea. They could hardly have done anything to prevent the raids in any case.

By the beginning weeks of the 1937 NNL season, the Crawfords had been destroyed. They had lost nine men to Trujillo, including stalwarts like Paige, Leroy Matlock, Cool Papa Bell, and Sam Bankhead. The only experienced pitcher remaining was journeyman Barney Morris. Suddenly, Oscar Charleston was forced to scramble to put together a credible club. For half the season, the Craws surprised and impressed with their gutty, heads-up play. Bassett acquitted himself particularly well. But neither his emergence nor the no-name Crawfords’ grittiness was enough to keep the club afloat in the competitive NNL. By the beginning of August, the Craws had slid back to fifth place. That is the position in which they would end. The 1937 Crawfords posted an abysmal 18-35-1 record against major black teams.

Paige, Bell, and the rest of the “outlaw” players who had been lured to the Dominican in spring 1937 returned stateside in late July and, by the beginning of the following season, were restored to the NNL owners’ good graces. But when Satchel held out for more money the following spring, Greenlee reluctantly agreed to trade him for Schoolboy Johnny Taylor. Meanwhile, Charleston tried to put together a quality team that could actually compete for a pennant. Things were so bad that open tryouts were held during spring training. By the time the season started, the Crawfords did not look like a very promising group. The team featured some solid veterans in Matlock, Sam Bankhead, and infielders Harry Williams and Chester Williams, as well as some rising talents in Johnny Washington, Pepper Bassett, Schoolboy Johnny Taylor, new outfielder Gene Benson, and new third baseman Bus Clarkson, but it lacked elite talent.22 For much of the season the club overachieved, even managing to put together an impressive 13-7 record as of June 25. Alas, in July, things unraveled, thanks in part to a six-game series sweep suffered at the hands of the Grays. It didn’t help that, according to one columnist, Taylor was “doing most of his pitching in night clubs.”23

The Crawfords still finished the 1938 season with an impressive 24-16 record, good for fourth place in the league and just 4½ games out of first.24 They were even supposed to play in a four-team playoff with the Homestead Grays, Philadelphia Stars, and Baltimore Elite Giants that was to serve as a new kind of NNL championship series. But the Grays refused to participate, and the series never came off. Its failure was a fitting symbol of the Negro National League’s persistent dysfunction.

Overall, from 1932 through 1938 the Crawfords went 299-218-14 versus major Negro Leagues teams; the club’s winning percentage in 1932-36, before it was busted up by Trujillo’s raid, was a robust .617. The 1938 season was the last the Crawfords would play with Pittsburgh as their home base – or with Greenlee as their owner. By 1939, Greenlee’s finances were in bad shape.25 He could not even properly maintain Greenlee Field, which in any case was dismantled to make way for a New Deal housing project. In mid-April, Greenlee sold the Crawfords to a group of Ohio businessmen.26 Their first move was to sign Charleston as the rechristened Toledo Crawfords’ manager. The legendary Oscar, they figured, would help draw fans. But the Craws’ new owners had another, even bigger card to play: one of their number was none other than the dazzling star of the 1936 Berlin Olympics: Jesse Owens.

The Toledo group was not well-heeled. Years later, the daughter of the lead investor, promoter Hank Rigney, estimated that her father and Owens had both probably invested no more than $50 in the venture.27 With little margin to spare and the Depression refusing to lift, the Crawfords’ new owners were betting in part on their promotional abilities, in part on Charleston’s appeal to black baseball fans, and in much larger part on the extraordinarily popular Owens’s ability to attract both black and white fans who would otherwise rarely, if ever, come to a baseball game.

By spring 1939, Owens was 25 and had a wife and three children. He had been scrambling for several years to capitalize on the fame he had won at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. For a brief while, Jesse had made good money as a celebrity spokesman (most notably for 1936 Republican presidential nominee Alf Landon), but as he spent freely and supported family members and old friends generously, his funds had rapidly diminished. In summer 1938 he had invested much of his remaining savings in a dry-cleaning company on Cleveland’s east side, but the business failed to turn a profit. In the meantime, the Internal Revenue Service had put a lien on his home for failure to pay income taxes. The result was that, in May 1939 – shortly after he helped purchase the Crawfords – Owens filed for bankruptcy. The Toledo Crawfords’ new co-owner had no head for business.28

Owens was, however, entirely willing to race for money, and that was what the Crawfords needed more than anything else. For the next two years, the usual Crawfords program called for Owens to put on a running exhibition between games, if a doubleheader had been scheduled, or after the game, if not. Usually Owens raced other players and fans. Sometimes he raced motorcycles or even horses. Although he ran frequently on muddy fields or a bum ankle, and almost always after enduring the grueling rigors of Negro Leagues travel, Owens usually emerged victorious, and he always earned the gaping crowd’s admiration.29

Later, in his memoirs, Owens looked back at this period as a degrading and humiliating way to have had to make a living, not recording the name of the team he traveled with (and co-owned) or that of anyone else with whom he partnered in the baseball world.30 Whether any of the Crawfords thought Owens’s role a degrading one is unknown, but it is certain that they were still trying to win. Alas, despite having decent talent on the roster in the form of Schoolboy Johnny Taylor, Harry Kincannon, Johnny Wright, Bus Clarkson, and Jimmie Crutchfield, the 1939 Crawfords, thanks to their new position well west of the NNL’s other clubs, couldn’t even get many league games. At the end of the NNL’s first half, the Craws, sporting a record of 4-5-1, withdrew from the circuit. The next day they were accepted as members of the more geographically appropriate Negro American League, in which they finished the season with an 8-11-1 mark.

The next year, 1940, Charleston bought a stake in the Crawfords himself, and he persuaded his partners to split the team’s 1940 home games between Toledo and Indianapolis.31 Charleston spent the spring looking under every rock in the South and Southwest for undiscovered talent. In Atlanta he scored a huge find in a tall, skinny, raw country boy named Connie Johnson, whom he would help develop into a pitcher who would play professionally for more than 20 years, including five seasons in the majors.32 Nevertheless, the 1940 Crawfords were less competitive than ever. Owens stayed with the team all season, continuing to race between or after both home and away games, leading clinics, often speaking for a few minutes to the fans, and generally lending his championship aura to the Crawfords’ operation. Auras, alas, can only do so much. The Craws finished in last place in the 1940 Negro American League with a 6-17 record.

The once-mighty Crawfords had reached the end of their journey. After the 1940 season the club broke up, never to play as a major Negro League team again. Eight years later, the end came for the Negro National League as a whole, thanks to the beginning of a new chapter for African American baseball players. It was a chapter that came too late for most of the ex-Crawfords, but they could take some solace from the knowledge that their own persistence, toughness, and excellence had helped make it possible.

JEREMY BEER is the author of Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player, winner of the CASEY Award and SABR’s Seymour Medal. His writing on baseball and other topics has appeared in the Washington Post, the Utne Reader, the Washington Examiner, National Review, and Baseball Research Journal, among other venues. Beer is the principal partner at American Philanthropic, LLC. He and his wife live in Phoenix, Arizona.

Sources

All statistics and records given in this article come from Seamheads.com, the best source of statistics for the Negro Leagues. Note that the Seamheads database is continually being added to and refined, so that some of the numbers given here may shift as time goes on.

Notes

1 A fuller account of the Crawfords’ early years can be found in Rob Ruck, Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987).

2 Biographical information on Greenlee can be found in Ruck, Sandlot Seasons; James Bankes, The Pittsburgh Crawfords: The Lives and Times of Black Baseball’s Most Exciting Team (Dubuque, Iowa: William C. Brown, 1991); and Mark Whitaker, Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018).

3 “Crawfords Sign New Stars,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 27, 1931: 15.

4 “Paige Stops Grays as Crawfords Cop, 10 to 7,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 8, 1931: 15.

5 “Charleston Is Elected Captain,” Philadelphia Tribune, January 28, 1932: 11.

6 Al Monroe, “Speaking of Sports,” Chicago Defender, May 19, 1934: 16.

7 This record comes from Seamheads.com, accessed December 15, 2019. Ruck, Sandlot Seasons, 157, is the source for the 99-36 claim.

8 For Gibson and other Crawfords hitter statistics from 1932, see “Sez ‘Ches,’” Pittsburgh Courier, January 21, 1933: 15; the statistics reported there were clearly not solely compiled against major competition. Paige’s statistics are taken from Seamheads.com, accessed December 15, 2019, and therefore include only games versus top-tier teams.

9 The elements of the story may be found in the Pittsburgh Courier, October 14, 1933: 14, and “Baseball Moguls to Meet in Philly Next Month,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 27, 1934: 15.

10 For this story, and for much else on Paige, see Larry Tye, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend (New York: Random House, 2009), 89-90. See also “Satchel Paige Hurls Bearded Nine to Title,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 25, 1934: 7.

11 Timothy Gay, Satch, Dizzy, and Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball before Jackie Robinson (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 75.

12 Gay, 76.

13 Rich Puerzer has sifted through the inconsistent media coverage to provide a coherent account of this series. “The 1935 Playoff Series: The New York Cubans vs. the Pittsburgh Crawfords,” presentation delivered at SABR’s Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference, Pittsburgh, August 7, 2015.

14 Forbes told John Holway this story. See John B. Holway, Black Giants (Springfield, Virginia: Lord Fairfax Press, 2010), 5-6, and John B. Holway, Josh and Satch: The Life and Times of Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988), 82. Forbes, however, is an unreliable source for the game’s details (and for much else).

15 Bankes, 85.

16 Bankes, 73.

17 Chester L. Washington, “Sez Ches,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 9, 1936: 14.

18 The Crawfords became involved in a brief controversy near the end of the 1936 season when columnist Dan Parker of the New York Daily Mirror charged them with throwing a game against the white semipro Brooklyn Bushwicks. (Gibson dropped a popup when the Bushwicks had the bases loaded in the bottom of the ninth; to anyone who knew Josh’s troubles with pop flies there was nothing fishy in that all, but Parker was apparently not clued in.) Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, overstepping his authority per usual, was said to have even interviewed members of the Crawfords about the affair. In the end, Parker retracted his claim. See Donn Rogosin, Invisible Men: Life in Baseball’s Negro Leagues (New York: Atheneum, 1983), 114-15.

19 W. Rollo Wilson, “National Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 26, 1936: A5.

20 Buck Leonard with James A. Riley, Buck Leonard: The Black Lou Gehrig: An Autobiography (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1995), 79.

21 Tye, Satchel, has the best discussion of this affair. See 110-16. Other details are taken from newspaper accounts.

22 The 1938 contract between Taylor and the Crawfords called for him to be paid $400 per month between May 15 and October 1. It was signed by Taylor, Greenlee, and Charleston (as witness). The four-page document disproves the notion that Negro Leagues players did not have formal contracts. See sports.ha.com/itm/baseball/1938-39-pittsburgh-crawfords-negro-league-player-s-contract-for-johnny-schoolboy-taylor-signed-by-oscar-charleston/a/7100-80064.s?ic4=GalleryView-Thumbnail-071515.

23 Wendell Smith, “Smitty’s Sport Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 16, 1938: 16.

24 This record comes from the Center for Negro League Baseball Research. See cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20National%20League%20(1920-1948)%202016-08.pdf. Seamheads has the Crawfords at 22–22–1.

25 “Sammy Bankhead Will Play with Toledoans,” New York Amsterdam News, April 22, 1939: 19.

26 “Oscar Charleston to Manage Strong Toledo Nine in NNL,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 22, 1939: 17; Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 22, 1939: 17.

27 John Wagner, “Swayne Field Was Full of History,” Toledo Blade, October 5, 2001. See toledoblade.com/Mud-Hens/2001/10/05/Swayne-Field-was-full-of-history.html.

28 I take this biographical information about Owens largely from William J. Baker, Jesse Owens: An American Life (New York: The Free Press, 1986).

29 For a more extensive account of Owens’s time with the Crawfords, see Jeremy Beer, Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019). Two representative articles about Owens’s racing are “Doubleheader and Jesse Owens at Park Monday,” Lima (Ohio) News, June 4, 1939: 15, and “Jesse Owens Dazzles Louisville People,” Atlanta Daily World, September 8, 1939: 5.

30 See Jesse Owens with Paul G. Neimark, Blackthink: My Life as Black Man and White Man (New York: William Morrow, 1970), 49-50; Jesse Owens with Paul G. Neimark, I Have Changed (New York: William Morrow, 1972), 71; and Baker, Jesse Owens, 143.

31 “Toledo Crawfords Here Sun., May 26 at Stadium,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 18, 1940: 14.

32 See Johnson’s account of coming to play for the Crawfords in Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited: Conversations with 66 More Baseball Heroes (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 114-16.