Spring Training for the 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords

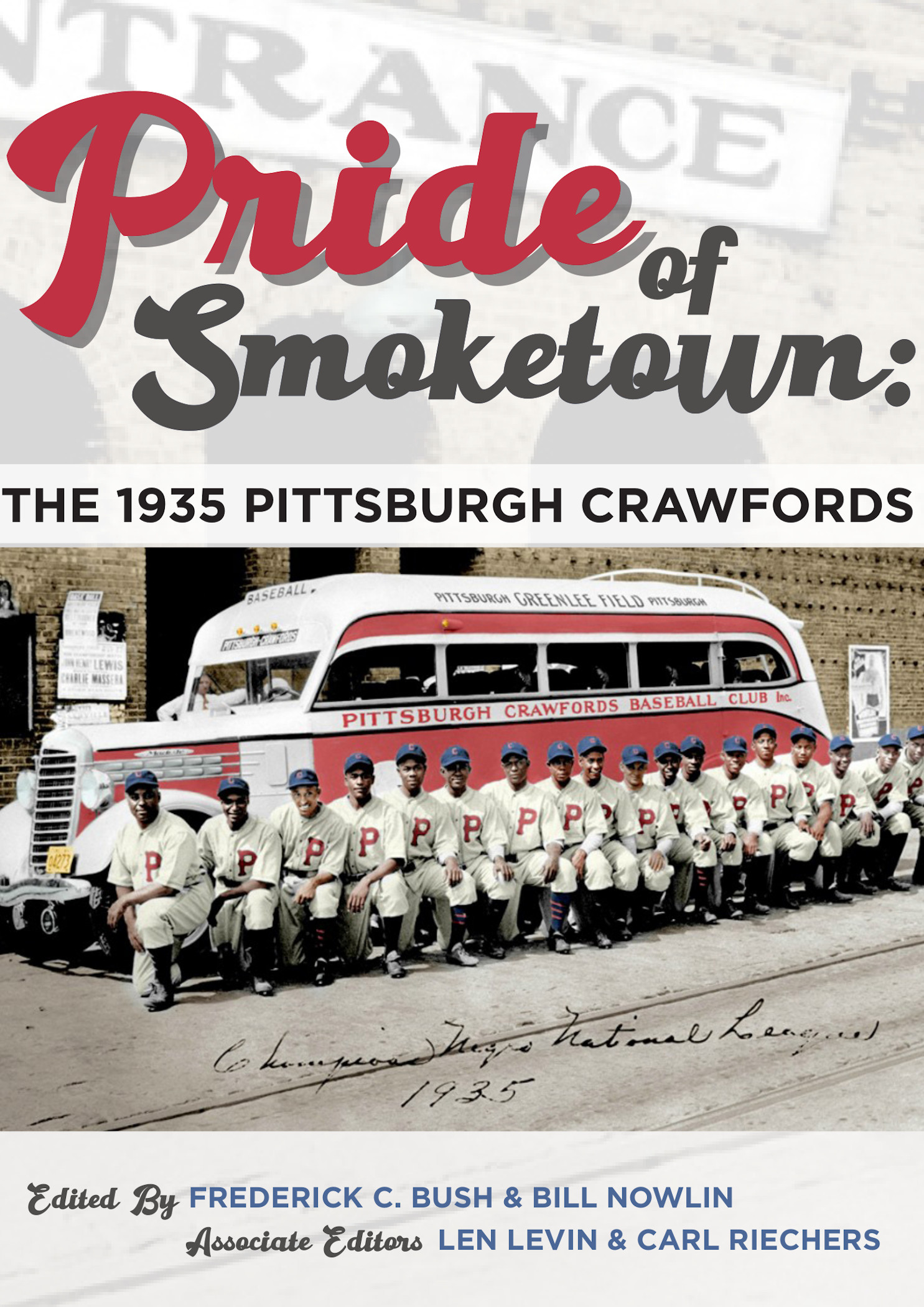

This article appears in SABR’s “Pride of Smoketown: The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords” (2020), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Baseball spring training had a long run in Hot Springs, Arkansas, from 1886, when the Chicago White Stockings came to town, to 1955, when the Detroit Stars prepared there for their season. Within this timeframe, individual players also traveled to Hot Springs to take thermal baths in the 4,400-year-old spring water that emerges every day on one hillside at an average of 143 degrees Fahrenheit. The water is, of course, cooled to a safe temperature for use in the tubs. These spa baths – and related activities, like Swedish-style massage and trail hiking in Hot Springs Reservation1 brought millions of health-seekers to the Ouachita Mountains of southwest Arkansas. A host of physicians, in Hot Springs and elsewhere, prescribed a three-week bathing course for a variety of ailments. Consequently, ballplayers were only engaging in what the general public had done for at least two centuries. While modern science holds a more limited view of the mineral water’s reputed medicinal power, the baths can still be obtained there today.2

Baseball spring training had a long run in Hot Springs, Arkansas, from 1886, when the Chicago White Stockings came to town, to 1955, when the Detroit Stars prepared there for their season. Within this timeframe, individual players also traveled to Hot Springs to take thermal baths in the 4,400-year-old spring water that emerges every day on one hillside at an average of 143 degrees Fahrenheit. The water is, of course, cooled to a safe temperature for use in the tubs. These spa baths – and related activities, like Swedish-style massage and trail hiking in Hot Springs Reservation1 brought millions of health-seekers to the Ouachita Mountains of southwest Arkansas. A host of physicians, in Hot Springs and elsewhere, prescribed a three-week bathing course for a variety of ailments. Consequently, ballplayers were only engaging in what the general public had done for at least two centuries. While modern science holds a more limited view of the mineral water’s reputed medicinal power, the baths can still be obtained there today.2

Teams and individual players could choose from dozens of hotels, some of which provided the baths. Other bathhouses operated without sleeping accommodations, including the famous Bathhouse Row in what is now the national park adjoining the city of Hot Springs. These hotels and bathhouses, however, were racially segregated during the Jim Crow era.3 Integration of facilities was assured in 1963 after “two national officers of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People tested the Buckstaff Bathhouse for nondiscrimination on March 28.”4

A number of ballparks were built for visiting and local teams. At the height of the spring-training phenomenon in Hot Springs, circa 1911, one might have encountered “about 200 major league players of national importance [practicing] at the Spa” in a single vernal season, not to mention minor leaguers.5 Never to be outdone, African-American aggregations began to visit Hot Springs for games by at least the 1890s. Their players were enticed into the federally regulated bathhouses by 1920, and Negro Leagues teams were conducting spring training in the tourist destination by at least 1927, when the Kansas City Monarchs and Memphis Red Sox trained there. The Monarchs returned in 1928 and stayed at the Woodmen of Union Hotel. In 1930 and 1931 the Homestead Grays set up camp at the Spa City, and in 1932 the Crawfords followed suit.6

Dick Lundy sent his Newark Dodgers to train at Rocky Mount, North Carolina, in 1935, but he himself went first to Hot Springs. An April 6 newspaper article revealed that he “left last Thursday for Hot Springs, Ark., where he will take the baths. While at Hot Springs, Lundy will train with the Pittsburgh Crawfords, who are doing their spring training at this noted health resort. … He will also look over a few promising youngsters, who are at Hot Springs. …”7

On April 12, 1935, a Wichita newspaper, the Negro Star, reported, with a Hot Springs dateline: “The Pittsburgh Crawfords blew into town this week to establish their spring training camp. Gus Greenlee, owner of the Crawfords, declares that the Crawfords will be right in the hottest part of the race for the Negro National League flag. Here with the Crawfords are: Satchell [sic] Paige, Betrum [sic] Hunter, William Bell, Sam Streeter, H. Kincannon, Roosevelt Davis, Alfred Carter, Wm. Harvey, Carl Howard, C. Cook, J. Johnson, C. Williams, Bond, M. Charleston, J. Crutchfield, S. Bankhead, T. Gibson, H.G. Perkins, Taylor, J. Bell, L. Palm, Curtis Harris, Paterson, Vincent and W. Breen.”8 The list in the April 12 paper seems to have been largely copied from the March 23 edition of the Pittsburgh Courier, and is not an eyewitness record of the team members who were in Hot Springs at that juncture.

The Pittsburgh Courier of April 13 carried text and photos of players at Hot Springs. Featured was an image of the Crawfords players standing in a line at a location here, with captions – “Left to right: Bond, Crutchfield, Hunter, Howard, Streeter, Davis, Palm, Bankhead, Perkins, Bell, Kincannon, Judy Johnson, Matlock, Taylor, Carter, Gibson, Schofield and Charleston. Kneeling, Trainer Whitten [sic];” a picture of club owner Gus Greenlee, in team uniform, with Josh Gibson and Crawfords bus driver Mack Hart; plus a photo of non-Crawford players Kenneth “Ping” Gardner (perhaps hoping to restart his career, he appears to be wearing a Crawfords jersey), Biz Mackey, and Dick Lundy, who were training there independent of their own teams.9 The “Ches Sez” column on the same page states, “And Gus sends word from the famous Spa that the Craws are taking baths regularly and that the sunny Hot Springs atmosphere is sure to put the boys in great shape for the hard National Association grind.”10

The April 27 Chicago Defender also reported that “[t]he Crawfords are in training at Hot Springs.” A team photo taken by a Defender photographer that spring indicates that the team members “(left to right) are: front row: Bond, Howard, Hunter, Streeter, Kincannon, Davis; middle: J. Bell, Bankhead, Charleston, Palm, Crutchfield, Carter, Perkins; top: Taylor, Johnson, Matlock, Schofield, Gibson, Whitten [sic].”11 More complete IDs for these men, sometimes with nicknames, can be found in numerous sources.12 The team makeup in the Defender photo caption matches that accompanying the April 13 Courier image but differs from the Negro Star list by the absence of Paige, Cook, Harris, Paterson, Williams, William Bell, Vincent, and Breen, and the inclusion of Matlock and Schofield. Schofield was “‘Lefty’ Schofield, another promising young portsider.”13 Paige never showed up in the spa town that April. One newspaper reported he was “A.W.O.L. at the ‘Craws’ training camp in Hot Springs,” despite being under contract to the Crawfords. Paige never did join the Crawfords in 1935 and spent most of the season playing for a semipro team in Bismarck, North Dakota.14

It seems fair to speculate that Cook, Harris, Paterson, Williams, William Bell, Vincent, and Breen were also absent from Hot Springs during the Crawfords’ 1935 training session, as no record of their presence here that year – other than the suspect Negro Star piece – was found. Of course, some of these players may have joined the Crawford contingent after the photographs were taken, or they simply may have missed the photo sessions despite being in Hot Springs.

Both the Courier and Defender photos appear to have been taken at what was originally christened Fogel Field, when it was built in Hot Springs for the 1912 Philadelphia Phillies (a team then owned by Horace Fogel). This diamond was located behind a pair of recreational attractions, the Alligator Farm and the Leap the Dips roller-coaster, both on Whittington Avenue. Presumably, Fogel Field (or Older Field, as it was sometimes called during the 1930s) was where the Crawfords trained, since nearby Ban Johnson Field at Whittington Park, directly across Whittington Avenue, would have been temporarily occupied by the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers, who trained in Hot Springs that year until April 13, as well as the St. Paul Saints, who worked out until April 11.15

Where the 1935 Crawfords quartered while in Hot Springs has not been pinpointed. Several African-American hotels were operating here, including two – the Pythian and the Woodmen of Union – that also offered thermal baths with spring water piped from the national park.16 One might suspect that they stayed at the Woodmen of Union, based on this observation about the team’s 1932 visit: “John L. Clark, traveling with the [Crawfords], praised not only the mineral water, but also the Woodmen of the Union Hospital and its doctors.”17 On the other hand, a 1991 newspaper article conveyed the reminiscences of 80-year-old Jimmie Crutchfield about Hot Springs in 1932: “On any given day, the same guy might wind up pitching and catching and driving the bus. The players slept most nights on makeshift beds in a bath house. If a white team showed up to claim the hardscrabble diamond that morning, [Crutchfield] and the rest of the Pittsburgh Crawfords were driven out of town and training began with a 5-mile walk through the Arkansas hills back into Hot Springs. The bills were picked up by a numbers runner back in Pittsburgh. ‘And that,’ he recalled, ‘was when things were good. We used to eat on 65 cents a day, and the luckier ones had a few dollars in their pockets left over from working in the offseason,’ Crutchfield said. ‘We knew the (white) big leaguers had it better, but we definitely loved what we had. …’”18 As for their manager, Oscar Charleston: “‘We had only 10 days down there, but Oscar, he was one of those hard-driving guys from the old school,’ Crutchfield said. ‘And he got us ready to play.’”19 We do not know whether the Crawfords’ 1935 sleeping accommodations in Hot Springs resembled those Crutchfield described in 1932, but owner W.A. “Gus” Greenlee enjoyed sufficient wealth to pay for actual beds.20

Hot Springs offered cheap rooms to visitors of modest means, yet all but two of the African-American hotels lacked the very desirable thermal spring water. At that time, the Pythian and the Woodmen of Union would have represented the best available lodging. Both were located on Malvern Avenue, the town’s “Black Broadway,” and could boast of having their own bathhouses – and associated businesses. The WOU Building, for example, contained a 2,500-seat auditorium, a 100-bed hospital, a training school for nurses, a bank, and other services for patrons in the African-American community.21

The Pythian Hotel operated between 1914 and 1974; the structure has since been demolished. The Woodmen of Union was built in 1923, became the National Baptist Hotel in 1950, and closed in 1982.22 After lying vacant for many years, the National Baptist was rehabilitated for “low-income elderly housing.”23

It appears that the 1935 Crawfords arrived at Hot Springs in early April to train for the coming season and that they departed by bus in time for barnstorming games in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 13 and 14. These were the first of numerous exhibition contests in which the Craws participated on their route back to Pittsburgh.

Their first home game of the season was against the New York Cubans on May 11 at Greenlee Field in Pittsburgh, and they defeated the Cubans, 6-5. The Craws’ training foray through the South was officially over.24

The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords were neither the first nor the last team from the Negro Leagues to hold spring training drills in Hot Springs, but they may have been the most formidable. Their presence added luster to the town’s unique history, a heritage that is now recounted along the Hot Springs, Arkansas, Historic Baseball Trail.25

MARK BLAEUER has since 2011 been a research team member for the Hot Springs, Arkansas, Historic Baseball Trail, along with Mike Dugan, Don Duren, Bill Jenkinson, and Tim Reid. Steve Arrison, CEO of Visit Hot Springs, headed and funded this project as well as the annual Hot Springs Baseball Weekend event. Mark got his BA from Illinois College and his MA from the University of Arkansas. He is a member of the Garland County Historical Society (Liz Robbins, executive director.)

Notes

1 The Hot Springs Reservation was a resource reserve created by Congress and President Andrew Jackson in 1832, to protect the hot springs and surrounding acreage. It was renamed Hot Springs National Park in 1921.

2 Don Duren, Boiling Out at the Springs: A History of Major League Baseball Spring Training at Hot Springs, Arkansas (Dallas: Hodge Printing Company, 2006); “Curry New Pilot of Black Barons,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 9, 1955: 23; “Hot Springs Geology,” nps.gov/hosp/learn/nature/hotsprings.htm; Sharon Shugart, “Hot Springs National Park,” in Isabel Burton Anthony, ed., Garland County, Arkansas: Our History and Heritage (Hot Springs: Garland County Historical Society and Melting Pot Genealogical Society, 2009), 345-356.

3 “African Americans and the Hot Springs Baths,” nps.gov/hosp/learn/historyculture/upload/african_americans.pdf.

4 Sharon Shugart, When Did It Happen? A Chronology of Events at the Hot Springs of Arkansas (Hot Springs, Arkansas: Eastern National, 2009), 58.

5 Duren, 326.

6 Dave Wyatt, “Rube Foster, as I Knew Him,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 27, 1930: 14; “Rube Foster and Johnson in South,” Chicago Defender, December 18, 1920: 6; “Negro National League Preparing for Spring Practice,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 12, 1927: 16; “Hot Springs, Arkansas, Is Picked as Training Camp for Kansas City Monarchs,” Chicago Defender, February 11, 1928: 9; “Grays Leave Spa for La.,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 29, 1930: 15; “Grays Show Fine Form at Springs,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 4, 1931: 14; “Crawford Vanguard Off for Hot Springs; Josh Gibson, Radcliffe Depart,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 20, 1932: 15.

7 “Newark Dodgers Off for Spring Camp; Look Great,” Chicago Defender, April 6, 1935: 16.

8 “Training Camp News,” Negro Star (Wichita, Kansas), April 12, 1935: 3.

9 “‘Gus’ at the Spa – Crawfords Conditioning at Hot Springs – ‘Bizz,’ Lundy,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 13, 1935: 16.

10 “Process of a Sports Editor Cleaning Up His Desk,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 13, 1935: 16.

11 “League Clubs in Training in Southern Camps,” Chicago Defender, April 27, 1935: 17.

12 E.g. Phil Dixon with Patrick J. Hannigan, The Negro Baseball Leagues: A Photographic History (Mattituck, New York: Amereon Ltd., 1992), 161. “Whitten” is identified as trainer Hood Witter.

13 “Crawfords Set to Make Strong Bid for League Championship,” New York Age, April 27, 1935: 5.

14 “Report or Be Barred from Ass’n, Warn Paige,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 6, 1935: 15.

15 Duren, 16; “Brewers Break Camp,” Akron Beacon Journal, April 13, 1935: 18; “Saints Break Camp,” Indianapolis News, April 11, 1935: 4.

16 “African Americans and the Hot Springs Baths.”

17 Thomas Aiello, The Kings of Casino Park: Black Baseball in the Lost Season of 1932 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2011), 60.

18 Jim Litke, “Negro Leagues Full of Drawbacks, Fun,” Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette. March 1, 1991: 15.

19 Litke.

20 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2002), 339.

21 “Hotels,” Polk’s Hot Springs City Directory (Kansas City and Detroit: R.L. Polk & Co., 1935), 494. Black-owned businesses were denoted by the symbol “(c)” in this volume, and included the Crittenden Hotel at 314 Cottage and the Hotel Johannah at 338 Garden; Garland County, Arkansas: Our History and Heritage, 148.

22 “African Americans and the Hot Springs Baths.”

23 “Woodmen of the Union Building, Arkansas,” nps.gov/articles/woodmen-of-the-union-ar.htm.

24 “Crawfords Win Home Opener,” Pittsburgh Press, May 12, 1935: 17.

25 hotspringsbaseballtrail.com.