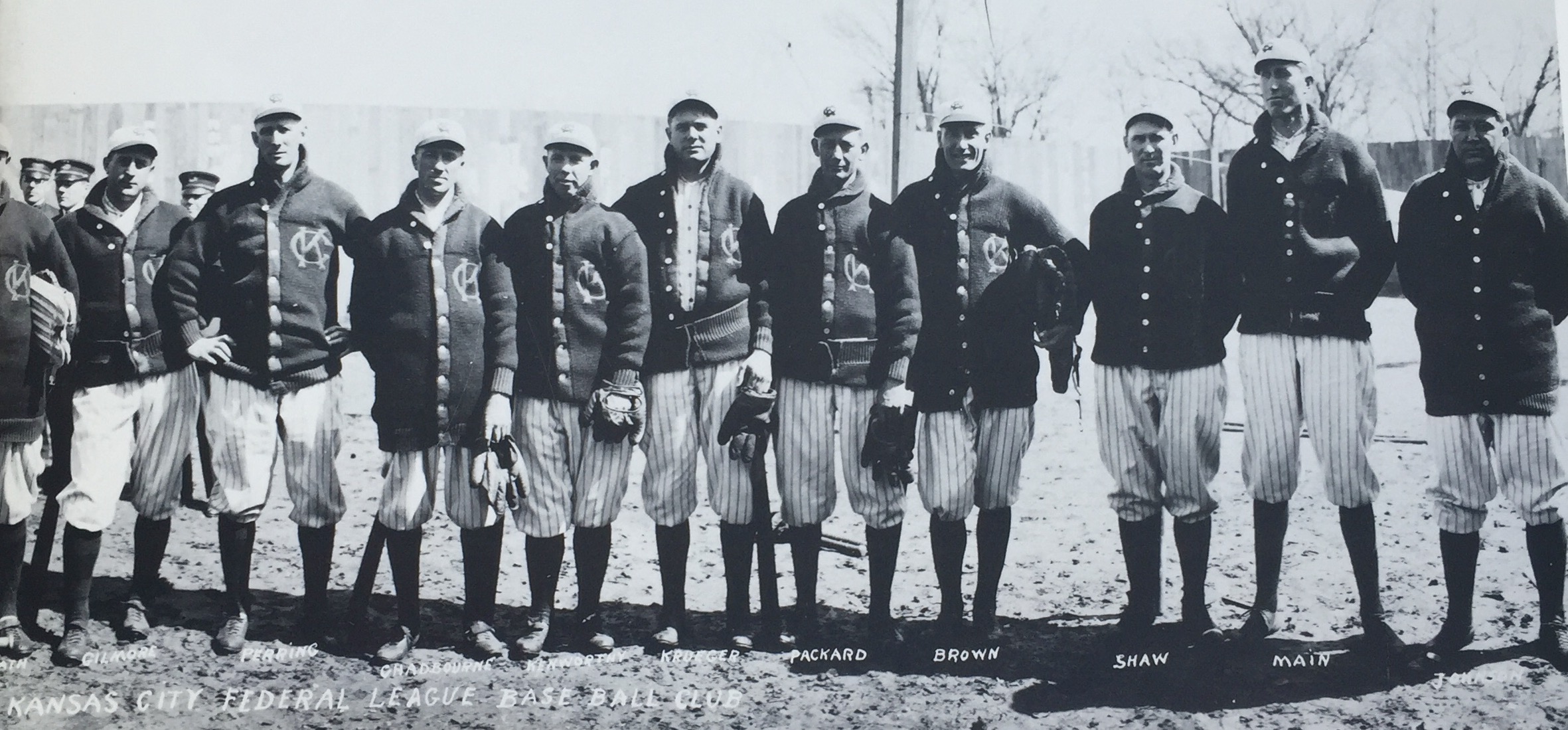

The 1915 Kansas City Packers

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in SABR’s “Unions to Royals: The Story of Professional Baseball in Kansas City,” the 1996 SABR convention journal. For a multimedia history of SABR conventions, click here.

Long forgotten by most Kansas Citians, the 1915 Federal League gave the city its first real major-league pennant race, and still it was one of the most exciting.

A mid-season replacement team in the league’s inaugural minor-league season of 1913, the Kansas City Packers were a true dark horse for its concluding one. Finishing a distant sixth place (67-84, 20 games out of first) in 1914, the franchise had barely survived the offseason, losing their ballpark to a flash flood in the waning days of the previous campaign, and just staving off the league’s attempt to move them to Newark. In the wake of those maneuverings, the Indianapolis franchise was transferred instead of Kansas City. Expected to finish again in the nether reaches of the standings, the Packers were the surprise team of the 1915 season, leading the league for a large part of the way, contending until the last few weeks. They never let up through the entire season.

This was a team with no stars; only a handful of its players had major-league careers of significant length. The pitching staff and starting lineup were both studded with unknowns and mediocrities, a Cinderella team if ever there was one.

There were some good players, but the team was mostly made up of career minor-leaguers (Chet Chadbourne), big leaguers having a last fling (Bill Bradley), young pros getting an early shot (Johnny Rawlings) or Walter Mitty one-shots (Ben Harris) who would have otherwise never seen major league play. Manager and first baseman George “Firebrand” Stovall — through as a player — proved himself an able manager and motivator, imparting his own combativeness and work ethic on the team. Figuring his major-league playing days over after the 1913 season with the Browns, he was the first bona fide major-leaguer to jump to the Feds (Joe Tinker was the first star to jump). The two years in Kansas City were a sweet homecoming for Stovall who was born in Blue Springs, Missouri.

Second baseman Bill Kenworthy hit 15 home runs in 1914 when the hometown fences were closer and shorter, but could only manage three this year. He remained a dangerous hitter with a .299 batting average and good doubles power.

Johnny Rawlings played 120 games at shortstop in 1915. He would go on to play 10 years with four National League teams, but this year he was a raw 22-year-old, overmatched at the plate and maladroit with the glove.

Chet Chadbourne was a great minor-league outfielder. His record was included in SABR’s first Minor League Stars. This year was his only real shot in the bigs (he had a couple “cups of coffee” otherwise), and he acquitted himself well, though he would find himself back in the minors in 1916.

Chet Chadbourne was a great minor-league outfielder. His record was included in SABR’s first Minor League Stars. This year was his only real shot in the bigs (he had a couple “cups of coffee” otherwise), and he acquitted himself well, though he would find himself back in the minors in 1916.

Grover Gilmore was a career minor-league outfielder whose only shot at the bigs came with Kansas City. His 108 strikeouts in 1914 was the second-highest season total at the time. His performance in Kansas City should have merited at least one more shot at the bigs, but his career was cut short by war and by death due by typhoid.

Al Shaw hit .324 in Brooklyn’s bandbox park in 1914, but proved to be a decent hitter in a less favorable park, hitting .281 while platooning with the right-handed Art Kruger. The platooning was somewhat unnecessary, however, as Shaw hit .344 against lefties while managing .272 against right-handers.

Shaw’s opposite number, Art Kruger, was a journeyman outfielder who was frequently mistaken for Art “Otto” Kreuger, so obscure was he. In his fourth, and last major league season, he was already past his prime.

Ted Easterly was the team’s primary backstop, and pinch-hitter deluxe when he wasn’t starting. Easterly was probably the premier pinch-hitter of the Deadball Era; his lifetime .296 average as a pinch-hitter still ranks among the top 10 (as of 1996).

George Perring was an undistinguished journeyman infielder, logging three partial seasons with Cleveland before becoming Kansas City’s starting third baseman and general utility player.

Bill Bradley wasn’t always the pathetic hitter he was reduced to by 1915. In fact, he was considered by many to have been the best third baseman in the American League’s history to that point. His 1902 29-game hitting streak was the AL record until Ty Cobb’s streak in 1911. By in 1915 it remained the 10th-longest of all time. He was frequently among the top hitters in the AL’s first five years (before a debilitating injury), and was still the leader in most AL lifetime fielding categories for third basemen. Now, however, he was nothing more than a coach and defensive replacement.

Norman Andrew “Nick” Cullop achieved a dubiously unique accomplishment in 1914 when he logged a 14-20 record while pitching in two different leagues. As unusual as it was to win 20 games split between two leagues, it was even a rarer feat to do the reverse. In the 20th century, only one other pitcher has done so, and baseball reference works are in dispute over Roscoe Miller’s “achievement” in 1902. Cullop turned himself around in 1915, going 22-11 for the Packers. He worked two decent seasons for the Yankees following the FL campaigns, but dropped back to the minors, appearing only briefly with the Browns in 1921.

Gene Packard, the team’s other southpaw pitcher, won 20 for the team in 1914, and matched his total in 1915, averaging 292 innings each year.

George “Chief’ Johnson, a Winnebago Indian, was the object of a noted lawsuit during the Federal League War, when the Cincinnati Reds won an injunction in an Ohio court to enjoin him from pitching for the Packs. Fortunately for the Packs, there were no Ohio teams in the Federal League, and the “Chief’ took an alternate route when the team traveled by train to Pittsburgh and Buffalo.

Beginning its season with an 8-0 loss to the Pittsburgh Rebels (named for their manager, “Rebel” Oakes), the team played .500 ball throughout April and early May, then began to win regularly, finally moving into first place with a 1-0 victory over Fielder Jones’ St. Louis Terriers on June 7. They continued to win, playing .600 ball through July 4.

The game of May 23 against the Buffalo Blues was an example of their fight and luck during this spell. Rallying from a deficit in the third, the Packs loaded the bases in the fourth against lefty Heinie Schulz, who had replaced a right-handed pitcher. Stovall platooned Shaw and Kruger in left field, and made the switch to Kruger at this juncture. Kruger gained his 30 minutes of fame, rewarding Stovall’s faith with a grand slam, only the third pinch-hit grand slam in major league history.

As summer wore on, the thinness of the Packers’ roster began to tell. They dropped back with the rest of the pack, fighting Pittsburgh, St. Louis, the Chicago Whales, and the Newark Peppers for the lead.

Stovall and the Packers fought for first place in quite a literal manner in a late-July series with Brooklyn. The Packs split a double-header with the Tip-Tops, and Stovall split the lip of umpire Corcoran. A planned “day” for Stovall was almost postponed when he was threatened with suspension.

The threat was not carried out, and “Stovall Day” went on as planned. The Packers regained first with consecutive double-header sweeps over the last-place Baltimore Terrapins on July 31 and August 1. The first three games were all decided by 2-1 counts.

That was the high mark of the season. The Packers then lost eight of ten games to fall to fourth place. They were fading, and needed a miracle. That miracle, albeit short-lived, came on August 16 in the form of Miles Grant “Alex” Main.

Main did not appear destined for fame on that hot afternoon in Buffalo. His only real claim to fame was that he was one of the tallest pitchers of the Deadball Era; Baseball reference works list him at 6-feet-5, but photographs suggest he was taller. He sported a 1-10 record for the season at that point. Fourth in the Packers’ rotation, his then-lifetime mark of 17-16 did little if anything to further the impression of a hurler bound for glory.

But on that August afternoon, he was nearly untouchable, giving the Packers a much-needed lift. Staked to a 3-0 lead before taking the mound, Main walked the game’s leadoff batter, retired the next three, and pitched a perfect second inning. Buffalo catcher Walter Blair led off the third with a sharp grounder to short that tied up Johnny Rawlings. He beat it out. After some argument among the sportswriters, the scorer ruled it a hit. That tainted hit loomed larger with each inning, as Main retired 21 of the remaining 22 men he faced, allowing only one other base runner in the 9th on an obvious error by second baseman Bill Kenworthy. Main faced only three over the limit in his 5-0 victory.

Main retired to the visitors’ clubhouse thinking he’d thrown a 1-hitter and was happy with a shutout win. Within moments, he learned that he now had credit for one better than that. Shortstop Rawlings, who would be charged with 46 errors that season, was glad to take credit for this one, too.

So Main’s accomplishment was greeted with rousing fanfare and celebration, right? Well, not exactly. The Kansas City Star carried the news in its late edition that day with a less-than-celebratory endorsement: ”The big hurler pitched what probably will go down in the records as a no-hit, scoreless game … ” The Buffalo Express was even more pointedly unenthusiastic the next day, going so far as to deny the no-hitter in print, listing the hit-turned-error as a hit-turned-error-returned-to-hit and gave the story a rousing headline of “Anderson or Schulz Will Pitch Today,” not even mentioning the game itself until the second paragraph.

In the course of a loss to Buffalo on September 11, Main suffered a freak injury. Following a foul ball, umpire Westerveldt tossed the ball back to Main. When the giant reached for the high toss, he dislocated his left shoulder. This injury would keep him on the sidelines for about a week. While throwing batting practice the next week in anticipation of a start the next day, Main was struck in the ribs by a line drive. This fracture ended his season.

The final home game was a victory for the Packs. It featured fistfights between Stovall and two Baltimore players, Jimmy Smith and Otto Knabe. Stovall reported that he had been spiked several times during the series by Terrapin players and had warned them that he would punch anyone who tried it again. Smith was the culprit today, and Knabe got into the fray as the manager. Stovall invited both men to step outside the park for a second round, but police broke up the scuffle between the two managers in the clubhouse.

Despite the victory, the Packers found themselves eliminated from the race when St. Louis won. While three teams were still in the chase, Kansas City was playing only for pride and for the memories.

September 29 was a memorable day for Gene Packard. Not only did the southpaw win his 20th of the season (making him the FL’s only two-time 20-game winner), but he performed a feat of pitching and hitting of remarkable rarity.

With a scoreless tie in the top of the sixth, Gene took advantage of the short right porch in St. Louis’ Handlan’s Field, and drove a ball into the seats for a solo home run. Davenport was invincible otherwise, yielding on four singles and no walks throughout the remainder of the game. Of course, Packard was even better, giving up only four singles (two of them scratches) and a walk, shutting out the Terriers 1-0. This was only the third time in major-league annals that a pitcher had won a 1-0 game with his own home run.

Davenport must have felt particularly snakebitten, as this was the third time this season Packard had taken a game from him by that minimum count. It left the Terriers in the unenviable position of needing to sweep the remaining three games against the Packs.

It looked all but impossible the next day when the Packs jumped to a 2-1 lead in the seventh by virtue of a triple steal, but Chief Johnson gave up a single to lead off the home half of the inning. Pep Goodwin gave the Terriers the tying run by allowing a dribbler to go through his legs, then throwing the ball away in his attempt to catch the runner. Another base hit, another error and a sacrifice fly plated a total of three runs, and the Terriers were still in the race.

All games around the league were rained out October 1. When play resumed, the Terriers were a half-game behind the Rebels, with Chicago a full game behind St. Louis. Dave Davenport returned to the mound to try to gain revenge on the Packers for his earlier defeats. For awhile it looked as if he would finally reverse the tables. He led 1-0, going into the fifth. However, he found the bases loaded with two out and his opposite number, Cullop, at the plate. Cullop did what any lifetime .149 hitter would do in that situation, he slammed the first pitch off the center-field wall for a double, scoring all three runners.

The Packers won the game, and St. Louis discovered to its horror that, although a half-game behind Chicago (who swept a twinbill from Pittsburgh) with one game left to play, the team had been mathematically eliminated from the race.

The final game went to the Terriers, 6-2, while the Whales and Rebels split, ending the season with the closest finish in major league history. The Whales finished 86-66, a won-lost percentage of .566; the Terriers were 87-67 (.565) and the Rebels 86-67 (.561). In the other leagues, the race would not have been over, as both Chicago and Pittsburgh would have had to make up their rainouts, but the Feds had no such provision. Despite protests from both St. Louis and Pittsburgh, the Whales refused to make up their game or agree to a three-team playoff. The season had a finish at least as controversial as the league’s beginning.

The Packs finished fourth, 5 1/2 games behind Chicago, with an 81-72 record, half a game better than Newark, which finished 80-72. Kansas City would not see as high a finish by a major league team for another 56 years.