The 1921 New York Giants

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2021 as part of the SABR Century 1921 Project.

1921 New York Giants team photo (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

1921 New York Giants team photo (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

The New York Giants and their manager, John J. McGraw, were optimistic that the 1921 season would result in a World Series triumph. Hopefully, this would end the frustration their fans had experienced since the team last won the championship, in 1905. While the Giants won National League pennants in 1911, 1912, and 1913, they were defeated by Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in both the 1911 and 1913 World Series. In 1912 they were on the verge of a championship, leading 2-1 in the bottom of the 10th inning of the deciding final game when Fred Snodgrass, a dependable outfielder, dropped a fly ball that led to two runs and a Red Sox victory. In 1917, with World War I as a backdrop, the Giants again won the pennant but lost the World Series in six games to the Chicago White Sox.

Another exasperating season was 1908. The Giants were in the midst of a pennant race with the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Chicago Cubs when they had victory snatched from them in a crucial late-season game against the Cubs. Fred Merkle, on first base, did not run to second on a hit and was forced out as the supposed winning run scored. The game had to be replayed at the end of the season with the Cubs winning and clinching the pennant. Merkle’s boner plus Snodgrass’s error left many Giants fans feeling their team was cursed.

In each of the three years leading up to the 1921 season, the Giants finished second but were well behind the Chicago Cubs in 1918, the Cincinnati Reds in 1919, and the Brooklyn Robins in 1920. Finishing behind the Robins was probably galling to McGraw; he was losing to another New York City team and one managed by Wilbert Robinson, with whom McGraw had a feud dating back to 1913, when Robinson was a coach with the Giants.1

McGraw’s optimism in 1921 was due to some significant additions in the past few years. Ross Youngs, an outfielder who made his Giants debut in 1917, was regarded as one of the premier players in the game. In 1919 Frankie Frisch decided to leave Fordham University to sign with the Giants and become the everyday second baseman. During the 1920 season, the Giants acquired Dave Bancroft in a trade with the Philadelphia Phillies to play shortstop. After spending several years between the major and minor leagues, George “High Pockets” Kelly appeared to cement his hold as the everyday first baseman. These four players plus holdover George Burns formed the nucleus of the Giants position players entering the 1921 season.

The pitching staff underwent a similar transition. In 1919 the Giants acquired Art Nehf from the Boston Braves in a midseason deal. Nehf won 21 games in 1920. Prior to the 1918 season, the Giants acquired Jesse Barnes in another trade with Boston. He won 25 games for the Giants in 1919 and 20 in 1920. Fred Toney was expected to be a key contributor. The fourth member of the rotation was Phil Douglas, whom the Giants acquired from the Chicago Cubs in a 1919 trade.

With this nucleus of position players and starting pitchers, McGraw had every reason to be optimistic. His high hopes were also shared by sportswriters; many picked the Giants to win the pennant. The principal opposition was expected to be the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Robins.

One other noteworthy change was the purchase of the Giants in January 1919 by a syndicate led by Charles A. Stoneham. Stoneham, a Jersey City native, was known as a playboy who enjoyed women, casinos, horse racing, and the Manhattan nightlife. McGraw was also part of the new ownership group.2

While the Giants were the favorite to win the pennant, their status as New York’s team was being threatened by the American League’s New York Yankees. After the 1919 season, the Boston Red Sox sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees. In 1920 Ruth hit 54 home runs, leading the Yankees to a third-place AL finish. They also became the first team to draw over one million fans, more than the Giants in the Polo Grounds, which the Giants owned and in which the Yankees had been a tenant since 1913.

The surge in the popularity of the Yankees resulted in the Giants deciding they no longer wanted them as a tenant and asked them to find a new place to play.3 The Yankees decided to build their own ballpark in the Bronx just across the Harlem River from the Polo Grounds. The Yankees moved into Yankee Stadium for the 1923 season.

What was especially aggravating to McGraw was the Yankees style of play. McGraw was a disciple of scientific baseball, which might now be characterized as “smallball.” McGraw believed in stealing bases, hitting behind the runner, and sacrifice bunts. The Yankees with Ruth were now relying on the home run and it appeared to be succeeding. Many were choosing the Yankees to win the 1921 AL pennant.

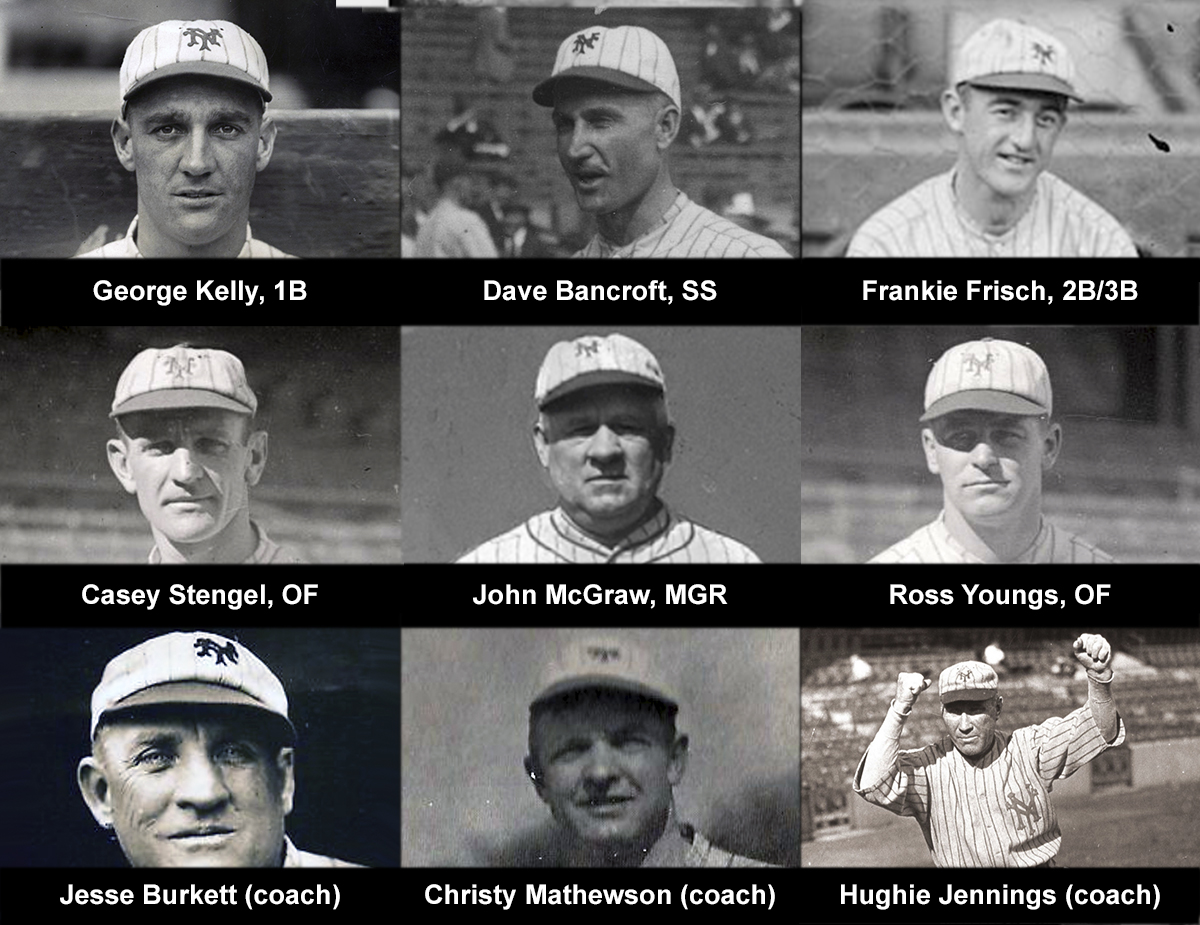

Future Baseball Hall of Famers

Top: George Kelly, 1B; Dave Bancroft, SS; Frankie Frisch, 2B/3B

Middle: Casey Stengel, OF, John McGraw, MGR; Ross Youngs, OF

Bottom: Jesse Burkett, Christy Mathewson, Hughie Jennings (coaches)

The Giants opened the season playing the Philadelphia Phillies at Baker Bowl in Philadelphia with Phil Douglas starting against Jimmy Ring for the Phillies. Douglas was not very effective and after four innings the Phillies held a 5-1 lead. The Giants rallied to take a 7-5 lead in the seventh inning but the Phillies tied the score in the bottom half of the inning. Neither team scored in the eighth, ninth, or 10th, but the Giants scored a run and then Kelly hit a two-run inside-the-park home run in the top of the 11th to give the Giants a 10-7 lead. The Phillies rallied but could score only one run and the Giants had an Opening Day 10-8 victory.

The Giants won the next day but lost the final game of the series. They went to Boston and beat the Braves twice, giving them a 4-1 record as they returned to New York to play the Phillies in their home opener. The Phillies got a quick lead but the Giants came back and the score was tied 5-5 as the two entered the eighth inning. Irish Meusel led off with a triple for the Phillies and scored on an error by shortstop Dave Bancroft. The Phillies held on to win 6-5. The Giants won the final two games of the series, giving them a record of 6-2 as they went to Ebbets Field to play the Robins in a four-game series.

The Robins proceeded to sweep the Giants in four well-pitched games as the Giants offense sputtered, scoring only seven runs in the four games. The Giants rebounded and won six games in a row. The first game of the streak was against the Boston Braves and saw the return of Ross Youngs to the starting lineup. He had missed the first 12 games of the season with a knee injury. The final two games of the winning streak were against the Robins at the Polo Grounds. The third game of that series was played at Ebbets Field while the Yankees were home at the Polo Grounds. The Giants continued their lack of hitting in Brooklyn as they lost 2-0 to end the winning streak.

The NL’s western teams were now scheduled to visit the Polo Grounds. The first opponent was the St. Louis Cardinals, who won the first game of a four-game series, 7-6, as Rogers Hornsby went 4-for-4. (The Giants had made an offer to the Cardinals for Hornsby but were rebuffed as the Cardinals wanted more than what McGraw was offering.4) Hornsby was probably the best hitter in the NL and McGraw may have wanted him not only for what he could contribute on the field but also to attract more fans given the emergence of the Yankees.

After the loss to the Cardinals, the Giants won eight in a row, culminating with a 3-2 win against Chicago on May 18. The Giants’ record was 20-8 but the Pirates also had a hot start and were 21-6, giving them a 1½-game lead over the Giants.

On May 19 Chicago snapped the Giants’ winning streak with a 5-3 victory. The two teams split the next two games. Pittsburgh was next to arrive for a two-game series and led the Giants by 3½ games. The Pirates won the opening game, 8-6, but lost the second so they left New York with the same lead.

With the homestand over, the Giants went to Boston for a five-game series and won three of five. They returned home on Memorial Day to play Philadelphia in another five-game series beginning with a doubleheader. Between games on that Memorial Day, the Giants placed a plaque on a monument in center field commemorating Eddie Grant, a former Giant, who had been killed in World War I.5

New York swept the doubleheader and won two of the next three games against the Phillies. Pittsburgh’s lead was now 2½ games as the Giants embarked on a 14-game road trip, beginning in Pittsburgh with four games.

New York won the first three games in Pittsburgh. After the third victory, a 12-0 shutout pitched by Douglas, the Giants found themselves in first place, a half-game ahead of the Pirates. Their lead was short-lived; they lost the fourth game, 5-4, putting Pittsburgh back in first place.

The Giants lost their next five games to Cincinnati and St. Louis before winning the last game of the St. Louis series, 6-4. The Giants ended the road trip by winning three of five games in Chicago. As they returned home to New York to play Boston in a three-game series, the Pirates’ lead was 3½ games.

The Giants lost the first two to Boston but won the third game, 10-4. Then they headed to Philadelphia for four games with the Phillies. They won the first three but lost the fourth. They went to Boston for a single game and lost 3-2. As July began, the Giants were still in second place, five games behind the Pirates.

Though idle on July 1, the Giants made a trade with Philadelphia, acquiring second baseman Johnny Rawlings and outfielder Casey Stengel for three players including third baseman Goldie Rapp. Rapp, who had been acquired by the Giants during the offseason, had been unable to hit major-league pitching. With Rawlings playing second, the Giants were able to move Frisch to third base, solidifying the lineup.6

After another idle day due to rain, the Giants played two consecutive doubleheaders. On July 3 at the Polo Grounds, they swept the Braves, then went to Brooklyn and won both games against the Robins. After the doubleheaders they returned to the Polo Grounds for an 18-game homestand. In the first two games, the Robins defeated the Giants. The NL Western teams were next scheduled beginning with the Cubs and Cardinals.

The first game against Chicago was a masterful pitching duel with the Giants winning 1-0 behind Art Nehf over Grover Cleveland Alexander. New York won two of the next three versus Chicago, then swept a three-game series with St. Louis.

Pittsburgh then arrived for a four-game series. The Pirates’ lead was three games. The teams split the series, so the Pirates left New York still three games ahead. Cincinnati was next for a four-game series, which the teams split. The homestand ended with a 4-3 victory against the Phillies and the Pirates still led by three games.

With high hopes of reducing that lead as they headed to Pittsburgh for four games, the Giants lost the first game, 6-3, but made another significant trade with Philadelphia. The Giants acquired Irish Meusel, a rising star, for two unproven players plus $30,000.7 The deal was criticized by Pittsburgh and other NL owners, who lobbied Commissioner Kenesaw Landis to veto the trade. Landis, who had stymied McGraw’s earlier attempts to trade for Heinie Groh, allowed the trade but later acknowledged that he should have negated the deal.8

After losing the first game, New York rebounded to win the next three, reducing the Pirates’ lead to just one game. The Giants then headed to Cincinnati for a six-game series, with doubleheaders on July 30 and 31 following a single game on the 29th. After winning on July 29 and splitting the first doubleheader, the Giants found themselves tied for first place with Pittsburgh. However, they lost both games on the 31st, falling a game behind the Pirates as July ended.

As August began, McGraw and the Giants had cause for optimism. They were just a game behind and now had Irish Meusel to bolster their lineup. However, the road trip proved to be somewhat difficult. After winning the final game in Cincinnati, they lost the first three games in a four-game St. Louis series. They rebounded to win the final game, 2-1, behind the pitching of Fred Toney. Then they split the four games in Chicago, and were three games behind Pittsburgh.

Back home for a prolonged homestand beginning with a four-game series against Brooklyn, the Giants won two of the four but were now 4½ games back as Pittsburgh kept winning. On Sunday, August 14, Philadelphia came to town for a two-game series, which the teams split. On August 16 the Robins beat the Giants, 7-6. Cincinnati was next for a three-game series. The Giants won two of the three but then lost three of four to St. Louis. The homestand was very disappointing; the Pirates lead was now 7½ games.

The Giants did have a faint glimmer of hope: Pittsburgh was coming to the Polo Grounds for a five-game series beginning with a doubleheader on Wednesday, August 24. The Pirates’ record was 76-41 while the Giants stood at 70-50. With a nine-game lead in the loss column and 37 games left in the season, Pittsburgh seemed like a sure thing for the pennant.

On the night before the series was to begin, McGraw, somewhat frustrated by the Giants’ August performance, called a team meeting. Supposedly he raged, “Pittsburgh is going to come in here tomorrow laughing at us. Pittsburgh is going to take it all. Pittsburgh! A bunch of banjo-playing, wise-cracking humpty-dumpties! You’ve thrown it all away! You haven’t got a chance! And you’ve only got yourselves to blame.”9

To illustrate the confidence of the Pirates, Barney Dreyfuss, the team’s owner, had extra grandstands and bleachers added at Forbes Field, Pittsburgh’s home ballpark. In addition, George Gibson, Pittsburgh’s manager, ordered his players to assemble before the first game of the doubleheader to have their team picture taken for the anticipated World Series program.10

Possibly McGraw and the picture-taking contributed to the Giants dominating both games of the twin bill. They won the first game, 10-2, behind Nehf, and Douglas shut out the Pirates in the nightcap, 7-0. The lead was now 5½ games. The next day, the Giants won again, 5-2, behind Fred Toney. For the fourth game of the series, Douglas was back again, pitching against Pirates hurler Earl Hamilton. Hamilton was effective, allowing only five hits and two runs. The Pirates could score only one and lost 2-1. With the lead now cut to 3½ games, Nehf was again the starting pitcher in the final game of the series, and he led the Giants to a 3-1 win. Pittsburgh was still in first place, by 2½ games, but was shaken as a result of the five-game sweep. Asked about the sweep, McGraw responded, “Not bad. But Pittsburgh is still in first place.”11

The Pirates were still up four games in the loss column and were playing most of their remaining games at home. However, the momentum had seemed to shift. The Giants swept Chicago in a three-game series while the Pirates won two of three at Ebbets Field. The Pirates’ lead was down to 1½ games.

The Giants lost four of their next six games, but Pittsburgh was also struggling. After defeating Philadelphia in both ends of a twin bill on September 7, the Giants were just a half-game behind the Pirates. This sweep of the Phillies was also the beginning of a 10-game winning streak. On Friday, September 9, after an offday on Thursday, the Giants defeated the Robins 6-2 while the Pirates lost. New York was in first place.

After seven more wins, the winning streak was snapped by the Pirates with a 2-1 victory behind Babe Adams at Forbes Field. The Pirates had lost the first two games of the series so the Giants left Pittsburgh with a 3½-game lead with only eight games to go.

The Giants continued their road trip with series in Chicago and St. Louis. They split the two games with the Cubs and the first two games against the Cardinals. On September 26 the Giants behind Nehf beat the Cardinals, 4-1, in the final game of the series while Pittsburgh was losing to the Phillies, 2-1. With the victory and the Pirates’ loss, the Giants clinched the pennant.

The Yankees won the AL pennant, setting in motion the first so-called Subway Series. Ruth had continued his prodigious hitting with 59 home runs. The Yankees began the best-of-nine series with both Carl Mays and Waite Hoyt of the Yankees shutting out the Giants by 3-0 scores. In Game Three the Yankees got an early 4-0 lead but the Giants came roaring back and won 13-5. Game Four also went to the Giants, 4-2, as Ruth hit his only home run of the Series. In Game Five, Hoyt once again beat the Giants, 3-1. Ruth laid down a perfect bunt in the fourth inning and scored the go-ahead run on a double by Bob Meusel, Irish’s brother. Ruth did not start any of the remaining games due to an inflamed elbow and sore knee.

Without Ruth in the Yankees lineup, the Giants won Games Six and Seven. The Giants led, four victories to three. The starting pitchers for Game Eight were Nehf and Hoyt. Nehf had already lost two games to Hoyt. The Giants scored a run in the first inning and led 1-0 going into the bottom of the ninth. (The Yankees were the home team.) To lead off the inning, Miller Huggins, the Yankees manager, called upon Ruth to pinch-hit. He grounded out to first. After a walk to Aaron Ward, Home Run Baker hit a vicious line drive that was fielded by second baseman Rawlings who got the out at first. Ward attempted to go to third but was thrown out by first baseman High Pockets Kelly, ending the game and the Series with a rather bizarre double play. John McGraw and the New York Giants had won their first World Series since 1905.

Sources

The Lyle Spatz and Steven Steinberg book 1921: The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012) was invaluable in providing a chronology of the Giants’ 1921 season. The author additionally relied on Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Photo credits: 1921 New York Giants team photo, SABR-Rucker Archive. Collage: SABR-Rucker Archive, The Sporting News, 1921 Christy Mathewson Testimonial Program.

Notes

1 Alex Semchuk, “Wilbert Robinson,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/wilbert-robinson/.

2 Bill Lamb, “New York Giants Team Ownership History,” https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/new-york-giants-team-ownership-history/.

3 Stew Thornley, “Polo Grounds/New York,” https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/polo-grounds-new-york/.

4 Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg, 1921 The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 119.

5 “Memorial Unveiling Today,” New York Times, May 30, 1921: 12.

6 “Giants and Phils in 5-Player Deal,” New York Times, July 1, 1921: 18.

7 “Irish Meusel Sent to Giants in Trade,” New York Times, July 26, 1921: 19.

8 Spatz and Steinberg, 185.

9 Noel Hynd, “The Giants of the Polo Grounds (Los Angeles: Red Cat Tales Publishing LLC, 2018), 325.

10 Hynd, 325.

11 Hynd, 326.