The True Story of Willie Mays’s Signing

This article was originally published in SABR’s Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series (2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

At 9:53 on the morning of June 21, 1950, a Western Union telegram arrived at the Memphis office of Tom Hayes, a local businessman who made his fortune in the mortuary business and helped give life to one of the greatest players in baseball history.

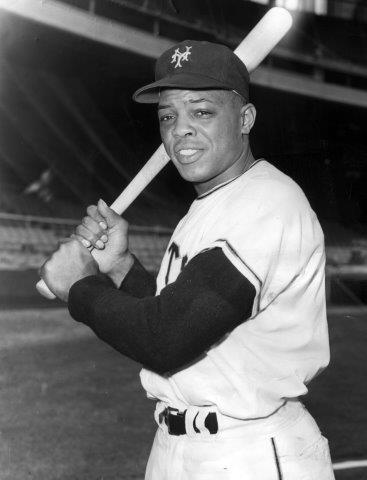

Hayes owned the Negro American League’s Birmingham Black Barons. Since the 1948 season, several major-league teams had pursued his teenage center fielder, astounded by the youngster’s raw strength, athleticism, and throwing arm.

However, in the initial years following 1947, scouting and acquiring black players remained a foreign endeavor for major-league teams, and a strong lack of trust festered on both sides. The result was the murky underworld of post-integration era baseball, where racial, social, and business lines blurred in an atmosphere baseball had never known. Extracting a player from the Negro Leagues was not simple, especially when it was the beloved son of Birmingham gifted with generational talent.

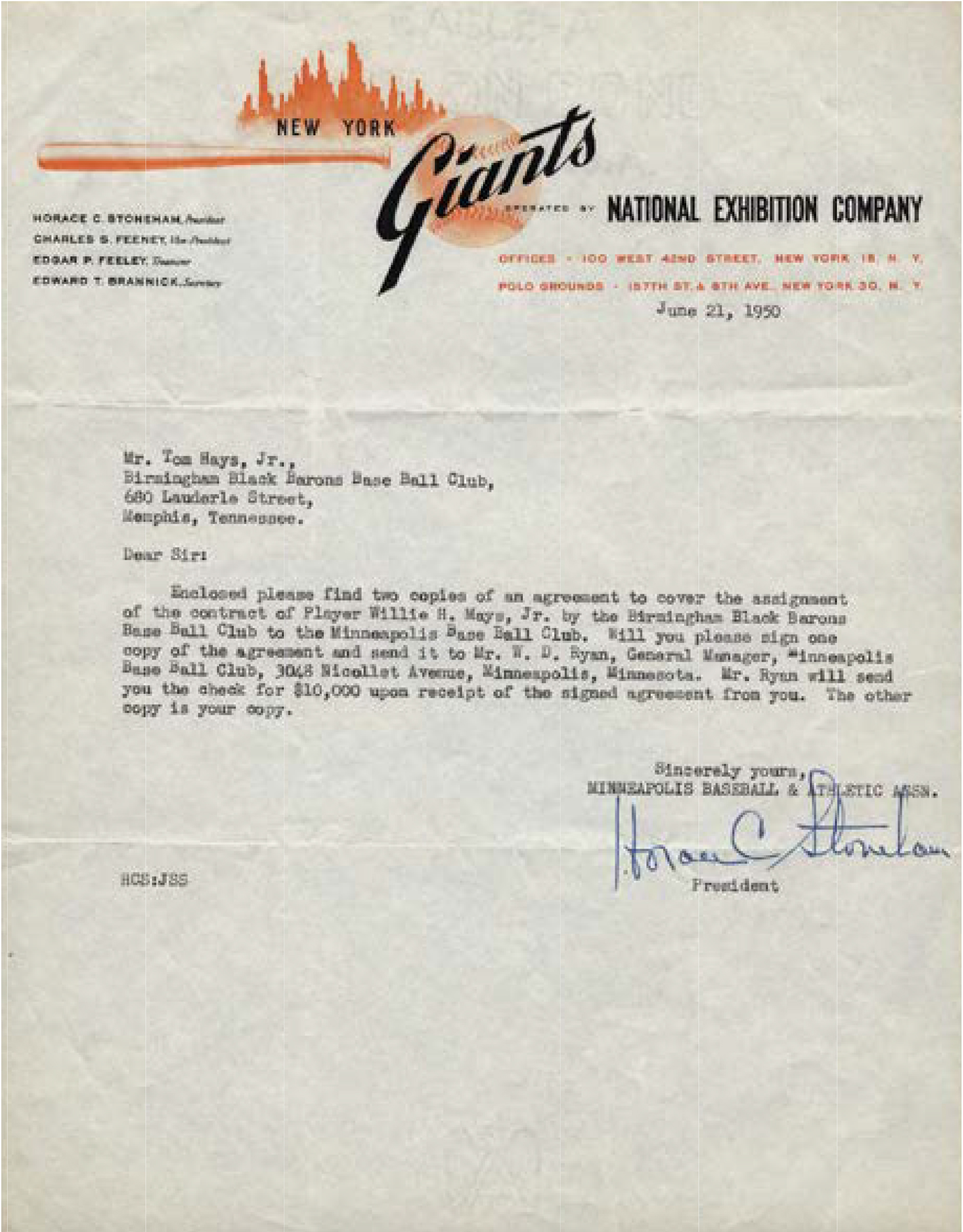

When the telegram from New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham finally arrived in Hayes’s hands, its simple confirmation belied a complex sequence of events that culminated two years of maneuvering and resulted in a historically significant transaction.

“THIS WILL CONFIRM TELEPHONE CONVERSATION TODAY WITH OUR MR. SCHWARZ IN WHICH WE OFFERED TEN THOUSAND DOLLARS FOR THE ASSIGNMENT OF CONTRACT OF PLAYER WILLIE H MAYES JR AND YOU AGREED TO ASSIGN HIS CONTRACT TO THE MINNEAPOLIS BASEBALL CLUB FOR THAT AMOUNT. HORACE C. STONEHAM”

In pencil, Hayes scribbled the words that sent Willie Mays to the world: “Accept your offer of $10,000 for Willie H. Mays Jr.”

The transaction was the conclusion of one of the greatest, yet little known, sagas in baseball history, the true story of how Willie Mays rode the underground railroad between baseball’s dying Negro Leagues to his stardom in the major leagues.

Letter from New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham to Black Barons owner Tom Hayes that accompanied an agreement in which Hayes sold Willie Mays’ contract for $10,000. (Courtesy of Memphis Public Library)

A childhood prodigy in baseball-rich Birmingham whose talents were well known locally for years, Mays officially broke into the Negro American League on July 4, 1948, signing a basic contract for $250 a month to play for the Black Barons. He was only 16, a high school student between his sophomore and junior years, but his talent allowed him to compete against men who had been in the league for years.

His guardian and mentor became Black Barons second baseman and manager Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, himself an all-star caliber second baseman who had once been considered a candidate to break major-league baseball’s color line.

Davis protected Mays and tutored him on the finer points of the game. Davis also had something most black players in Birmingham did not possess – first-hand experience with what the locals called “White Folks Ball.”

Davis gained a national reputation and an instinct for the machinations of player movements in white baseball. He also had years of experience in the northern states, which many southern players lacked. These nuances were completely foreign to young Mays. As important as Davis was to Mays’s maturation as a player, he was just as crucial in helping Mays navigate the process of escape through the complex world of black baseball to white. Mays was simply a greenhorn with great gifts; it was up to the community around him to safely deliver him to the world at large.

Davis was established in the black sporting world for his two-sport career as a basketball player for the Harlem Globetrotters as well as his baseball career with the Black Barons during the early 1940s. Mays would not have made it to the Giants were it not for the contacts Piper acquired, which were crucial to shaping the young outfielder’s career trajectory.

Davis’s former Black Barons manager and Harlem Globetrotters coach, Winfield Welch, was the field manager of the 1948 New York Cubans, owned by the flamboyant and savvy Alex Pompez. One reason Pompez hired Welch was to access the rich talent pipeline that existed in Birmingham thanks for the city’s industrial leagues, which fed the Negro Leagues and produced scores of stars, including Piper Davis. These players could help his Cubans win immediately and also give Pompez added inventory to offer the white clubs in the near future.

Pompez, a longtime New York sports promoter who had once been one of Harlem’s most successful operators of the “numbers,” a gambling racket in the 1930s, was ambitious and intelligent. He dreamed of making the remaining Negro League teams affiliated minor-league teams, so that black and Latin players could be easily scouted and bought by major-league teams at reasonable prices. Pompez’s dream was to keep the Negro League model of scouting and development alive in cooperation with major-league clubs, but to do that, he needed the right player to prove his vision and establish his own career in white baseball.

Pompez needed a big score to enhance his reputation. Mays was such a player, and therefore, no single Negro League ballplayer would mean as much to so many lives and affect so many careers as the path of Willie Mays. The first step of Pompez’s plan was to see to it that the Giants would see Mays play, not in Birmingham, but on their own front yard. So he made sure to let the Giants know when the Black Barons were coming to Harlem.

The first time Mays played at New York’s Polo Grounds, not as a member of the New York Giants, but in a doubleheader with the Birmingham Black Barons against Pompez’s Cubans, in May 1949.

That day, Pompez sold two of his star players, pitcher Dave Barnhill and third baseman Ray Dandridge, to Giants owner Stoneham and farm czar Carl Hubbell. Barnhill and Dandridge were older players slated for Triple-A rosters, and simply Pompez’s warm-up act to Hubbell to prove to the Hall of Fame pitcher that he knew how to evaluate young talent, a key factor in the selling of Mays.

Barnhill described his meeting with Hubbell that day, confirming Hubbell’s presence at the Polo Grounds when Mays first played there in 1949, well than a year before Giants territory scout Ed Montague claimed that he happened upon Mays. This means that Montague did not discover Mays, as he claimed for decades. His superior, Hubbell, saw him a year earlier, and began the organization’s following process.

Hubbell, the famed screwball pitcher who was then in charge of scouting and minor-league player acquisition for the Giants, had complete power and autonomy for signing and developing players, and he answered only to Stoneham. Signing black players in the early integration years, even to minor-league contracts, was an executive-level decision, not a territory-scout level decision. Pompez understood this division, and used his prestige as owner of Harlem’s black ball club that rented the Polo Grounds to build a relationship with his major-league landlords.

Moreover, as a friend and ally of Black Barons owner Tom Hayes in the years when Negro League owners were sharply divided over the future of Negro League baseball, he also had direct knowledge of Hayes’s price tag on Mays and access to the owner, both factors which eluded major-league teams interested in Mays. Many times, major-league teams did not even know how to contact Negro League teams.

Meanwhile, Mays continued to develop through 1949 and into 1950. He was no longer a well-kept secret. The Boston Braves made a run at signing Mays before he graduated from high school, but the front office hesitated at the high asking price. A decade later, Braves owner Lou Perini claimed that the Braves had been following Mays since 1945, well before he played for the Black Barons. Bill Maughn, the Braves territory scout, did more legwork than any white scout in Alabama, but lost out when his office paused. Maughn worked with integrity, but he did not understand how the black baseball underground railroad would circumvent his efforts to sign the player.

The Boston Red Sox signed Piper Davis in winter 1949 and sent him to minor-league spring training in 1950; Davis was the first black player signed by the Red Sox organization. Many Birmingham players believed the only reason the Red Sox signed Piper Davis was not because they viewed the beloved Piper as a prospect, but only to gain favor and access to Mays. Davis felt he had been treated poorly and that his performance did not warrant his release a few months later. Many in Birmingham believed that once the Red Sox found their efforts to acquire Mays through Davis insufficient, they cut him. Locals speculated that Hayes would not facilitate a deal for Mays with the Red Sox because a framework deal with Pompez to send Mays to the Giants already existed. His usefulness expired, Piper Davis was released and returned to the Black Barons.

The Birmingham community felt betrayed by the way Davis had been treated in the Red Sox organization. Hayes, in particular, would not reward the Red Sox for mistreating a player which meant much to his city and team. Birmingham did hold grudges and Mays would never become a Boston Red Sox.

The Cleveland Indians knew about Mays at least as early as 1948 because Harlem Globetrotter founder Abe Saperstein was scouting for Bill Veeck in an informal capacity. Veeck tried to sign Black Barons shortstop Artie Wilson after the 1948 season, but in another complex transaction, the deal got mucked up when the Yankees became involved and required Commissioner Chandler to formally award Wilson to the Yankees at a lower price than the Indians offered. This deal soured Hayes on White Folks Ball, and further cemented Mays to the Giants through the trusted connections of Piper Davis and Alex Pompez.

The Yankees and Dodgers were both informed about Mays, but declined to pursue him with intent. Each club had various degrees of information on him, but neither made a serious attempt to sign him.

The Chicago White Sox had a solid inside track thanks to its man on the ground. Former Negro League pitching legend John Donaldson was hired fulltime by the Chicago White Sox in 1949. He was the first fulltime scout dedicated to covering black players. Donaldson wanted Mays but couldn’t get his front office to commit, as a series of letters and documents shows.

Mays rewarded Piper Davis’s commitment to his growth. Mays played with the Black Barons for the first few months of the 1950 season, and with each game, it became more apparent that he was an impact player whose talents could not be contained to the remnants of the Negro League. Most white teams couldn’t understand why Hayes was so reclusive and skeptical, and he gained a poor reputation in white baseball, even though black players said he treated them with integrity and fairness.

The one person Hayes trusted, Pompez, had won the Giants over. Pompez knew as much as he did because of his connections to Piper Davis.

When Mays and the Black Barons returned to play Pompez’s Cubans in the Polo Grounds in early June of 1950, Hubbell and Stoneham had one more look at Mays playing a doubleheader. They loved what they saw. He was near major-league ready. They were ready to move once Mays graduated from high school.

Fearful that they would lose him if other teams found out they wanted him, Hubbell tapped power-hitting first baseman Alonzo Perry on the shoulder.

Perry had hit two home runs in the doubleheader and said he thought Hubbell wanted to sign him.

Instead, Hubbell asked him to confirm that Mays was indeed playing center field. Perry related this story to the Birmingham News after his playing career, another story that verifies Hubbell was already following Mays and wanted to make sure he had the right player.

Hubbell was looking for potential roommates for Mays, which was a common practice of major-league clubs in the early integration years. Perry would have been such a candidate, and the Giants never considered him a serious prospect. Hubbell, at the top of the chain of command, delegated the task of completing the transaction to Montague, his territory (area) scout, under orders of complete secrecy for the number of clubs pursing Mays. Birmingham players, including pitcher Bill Greason, said that the players knew Perry was a cover story for the Giants to keep their Mays a secret.

Perry, therefore, served as a decoy for Hubbell to dispatch two scouts to Birmingham, Ed Montague and Bill Harris, the following week. There was no such thing as the accidental discovery tale Montague told until it became accepted as fact, a historical fallacy still repeated today. The truth was Ed Montague had not the most to do with the Giants discovering Mays, as he often portrayed, but the least. Montague had no idea what was going on behind the scenes; he told what he thought was the truth; or at least omitted whatever back story he actually knew. It made for a good story for the New York papers, but as in many cases, there is a white history, and there is a black history.

Longtime Giants scout George Genovese confirmed Pompez was sent by Hubbell himself to Birmingham to negotiate with Hayes on behalf of the Giants. Montague’s job was simply to come to sign the player; in later years, Montague claimed he alone had stumbled onto Mays when sent to check Perry. That was a scout’s tall tale told to the white media in New York City and repeated as fact through the decades, but in truth, a photograph in the Birmingham News the weekend Mays was signed shows Montague with several other scouts in Birmingham for a white high school all-star game at Rickwood Field, while the Black Barons were still out of town. Montague didn’t just stumble onto Mays, as he claimed. He was waiting for him. He was sent to finish the work arranged by Piper Davis, Alex Pompez, and Carl Hubbell.

In an era where major-league teams raided Negro League teams for their best players, often without fair value, Mays was so important to the Giants that Hayes got the respect he felt he deserved. He wanted to be treated as an equal by major-league owners. He viewed himself as a successful, respectable businessman the same as white owners, and he believed he earned fair acknowledgement. Many white owners disdained Negro League owners as criminals and hustlers, but the Giants looked past what the rest of white baseball used as excuses to not sign black players. As a result, Hayes got what he wanted. He became the first black owner to receive a telegram from a major-league owner and he got something close to fair market value for the product he was selling.

Hayes had felt disrespected many times by major-league clubs, who he felt tried to buy his best players for below market value. Sometimes, he overpriced his players, perhaps intentionally, in order to keep his team together. His actions indicated that he would rather keep a player and pay him well in the Negro Leagues then sell him to white baseball just so his player could be paid less, play less, and be exploited.

Mays was too talented for the traps that befall other players from Birmingham. When the telegram came to Hayes’s office, the owner felt vindicated and bittersweet; the respect he had coveted from the major leagues came at the cost of the best player he would ever sell.

It was a two-part deal: Montague signed Mays to a basic minor-league contract for a $4,000 bonus and Stoneham paid Hayes $10,000 for Mays’s contract. Mays bitterly remembered how he never saw any of the $4,000. Genovese speculated that Pompez received a portion to the $4,000 as part of his commission, but most of the money went to Hayes.

That was the final move that made Mays a Giant for life.

The Giants in turn made sure Pompez and Davis were both rewarded for helping them obtain Mays finding creative ways to reward both for their help, another indication that the organization acknowledged that they would have never signed Mays without the help of the two men.

Pompez parlayed his role in the Mays transaction into a job with the Giants and became their key player runner in Latin America, responsible for such players as Juan Marichal, Orlando Cepeda, and the Alou brothers. He worked with George Genovese’s brother, Chick. George Genovese said Horace Stoneham felt guilty that Pompez’s New York Cubans eventually went out of business, as did the other Negro League teams. It was a symbolic gesture, but Pompez, over the years, made himself very productive.

When Piper Davis was sold out of Birmingham and to Ottawa in the International League in 1951, the parent club of Ottawa was the New York Giants, who then sold Davis into a favorable situation with the Oakland Oaks, where he became a productive and popular Pacific Coast League player. Davis’s strong reputation allowed him to stay in professional baseball for many years as a scout. He would forever remain connected to Willie Mays, but never once would he claim credit for any of his contributions.

For many years after, even when his income was such that he did not need the money, Mays continued to play for Pompez’s winter barnstorming tours through the deep south. The connections remained strong. When he was inducted into the Hall of Fame, Mays thanked Piper Davis, and retained fond memories of his beloved ’48 Black Barons.

When John Donaldson, the White Sox scout, learned that Mays had been bought by the Giants, he knew he would never have the chance to sign a player like Mays again. He wrote to Hayes, “Glad you sold Mays. I wish him the best of luck.”

JOHN KLIMA wrote “Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series and the Making of a Baseball Legend,” which was published in 2009. He followed up that book with “Bushville Wins!” in 2012 and “The Game Must Go On” in 2015. A former baseball writer, his story “Deal of the Century,” about the Paul Pettit transaction, appeared in the 2007 Best American Sports Writing. He has also contributed to several publications, including the New York Times. After several years in the baseball media, followed by a stint in the scouting community, which included an invitation to the Major League Scouting Bureau’s scout school, he parlayed his writing, research and scouting experiences into a boutique baseball agency called BPR Baseball, which he operates with his wife, Jen. John is currently a fully certified MLBPA Player Agent, along with Jen, who at the time of this writing is one of only nine fully certified female Player Agents in baseball. At the time of their MLBPA certification, John and Jen were the only fully certified husband and wife agent team in baseball.

Note

This article was adapted by the author from his book Willlie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2009).