The Vanishing 20-Game Loser

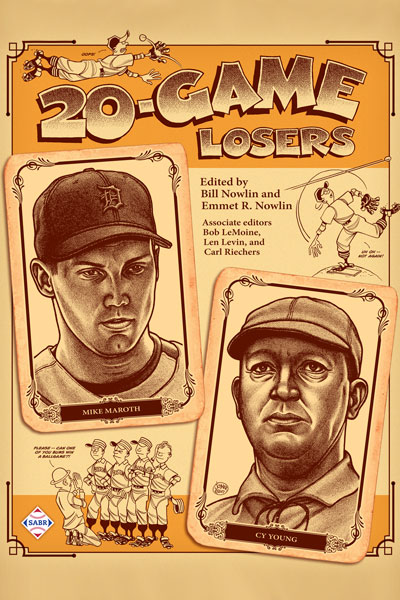

This article appears in SABR’s “20-Game Losers” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

On September 29, 2016, Chris Archer of the Tampa Bay Rays took the mound with a record of 8 wins and 19 losses. Facing the possibility of a 20-loss season, Archer pitched 6⅔ innings and beat the Chicago White Sox, 5-3. He never trailed in the game. And once again, the major leagues avoided having a 20-game loser.

On September 29, 2016, Chris Archer of the Tampa Bay Rays took the mound with a record of 8 wins and 19 losses. Facing the possibility of a 20-loss season, Archer pitched 6⅔ innings and beat the Chicago White Sox, 5-3. He never trailed in the game. And once again, the major leagues avoided having a 20-game loser.

The last pitcher to start a game with 19 losses and lose the game was Mike Maroth, who notched his 20th loss of the season on September 5, 2003, as Toronto defeated his Detroit Tigers, 8-6.

The last pitcher before Archer to start a game with 19 losses and avoid a 20th loss was Albie Lopez, who tossed a three-hit, complete-game shutout in Milwaukee on October 5, 2001.

In fact, the 20-game loser is now as rare as the pay telephone or the service station attendant who washes your windshield. Mike Maroth is the only man to lose 20 games in one season over the course of the last 36 years. But there was a time when 20-game losers were as common as knotholes in the outfield fence, when it was even possible to lose 20 games with an earned-run average below 2.00, when even men who would later enter the Hall of Fame lost 20 games. For the first decade of the twentieth century, the combined 16 major-league teams averaged 7.5 such hurlers a season. In the 45-year period from 1901 to 1945, only four seasons failed to produce a 20-game loser, and one of those was in 1918, when the number of games played were reduced due to World War I.

What changed? Despite the longer season introduced in the 1961 expansion, the shift to a near-universal five-man rotation, the rise of relief specialists, the reduction in the number of complete games because of pitch counts, and the enhanced minor-league affiliations that allow teams to demote players in midseason have contributed to the dearth and possible extinction of the 20-game loser. Even teams with more than 100 losses are able to spread the responsibility across a larger staff.

Like many 20-game losers, Archer was a good pitcher on a bad team. He had the most innings pitched and was second in wins and earned-run average for the 68-94 Rays. Many of the 20-game losers led their team in wins, ERA, or innings pitched, and several led in all three categories. For example, in 1952, Murry Dickson lost 21 games but topped the Pirates’ staff with 14 wins, 277⅔ innings pitched, and a 3.57 ERA. That year, the Pirates lost 112 games, and Dickson took credit for one third of their victories.

Five-man rotation

The 1903 Philadelphia AL team featured four pitchers who each started over 20 games. The rest of the staff combined for five starts. The 1975 Yankees had five pitchers who each started at least 20 games. The rest of the staff combined for only three starts. Although these are extreme examples, they demonstrate the shift from a pitcher starting every fourth day to one starting every fifth day.

The graph below shows the average number of pitchers per team who started at least 20, 25, and 30 games from 1901 to 2016. The data demonstrate a slight upward trend over time. Injuries, trades, and managerial decisions obscure the strict rotation that most teams have used. Doubleheaders, more common in the past, often require the use of an additional pitcher who would not otherwise start a game. Seasons shortened by war or strikes represent the anomalies.

If we remove the years with fewer than 150 games and average the results over decades, the trend is clearer. The number of pitchers who started at least 30 games has increased by almost one per team. The number of games is fixed at 162. With a four-man rotation, a pitcher might get 40 starts and about 28 decisions a year. With the five-man rotation, a pitcher gets 32 starts, which leads to about 22 decisions per year.

Fewer starts translate to fewer decisions, making it harder to lose 20 games in a season.

Relief specialists

In 1903, complete games were the norm, and almost all starters performed some relief. However, only Harry Howell pitched 10 games in relief, and he started 15. By 1984, 38 percent of all pitchers who started at least 10 games did not pitch at all out of the bullpen, and 54 percent of pitchers who relieved in at least 10 games never started.

|

Year |

Started at least 10 games |

Did not relieve |

Relieved at least 10 games |

Did not start |

|

1903 |

45 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

|

1984 |

155 |

59 |

187 |

102 |

The shift to relief specialists meant that relievers were earning a significant number of decisions, which reduced the number of candidates for 20-game-loser status.

Complete games

Nineteenth century star Will White started 402 games and completed 98 percent of them. Every team in 1901 had at least 107 complete games. In 2016, all teams combined for 83 complete games, and Chris Sale led the majors with six complete games. Blame the emphasis on pitch counts and the increased concerns about how high workloads can shorten a pitcher’s career. Teams now spend a great deal of money on closers, set-up men, and left-handed relief specialists for key moments of the game in the late innings. A manager now has many options and many excuses to remove a starter from the game even though the team is ahead and the starter is pitching well.

Fewer complete games mean fewer losses.

A managerial rule of thumb is to not remove a pitcher until he gives up five runs. However, in 2016, 42 percent of all starting pitchers were sent to the showers even though they had not given up five runs and the team was leading at the time. It has become more difficult for a starter to earn a loss once his team has the lead.

Minor-league affiliations

One hundred years ago, minor-league teams operated independently. Players were sold to higher-level teams. Today, most minor-league teams are affiliated with a major-league club. The parent club provides the players and moves players from one team to another as desired. So a pitcher who is performing poorly at the major-league level may be demoted and replaced by a promising rookie during the season.

The Boston NL team of 1901 used only five pitchers the entire season. Today, it is not uncommon for a team to use more than five pitchers in a single game. As a result, pitchers who are piling up losses may find themselves reduced to limited roles or demoted. In 2016, almost two-thirds of all major-league pitchers also spent time in the minor leagues. In 1901, that figure was less than one-fifth.

BARRY MEDNICK is a software engineer specializing in customer support and quality control. He has also taught at the college and high school level and currently tutors prospective teachers. Mednick holds a BS and MS from Columbia University’s School of Engineering where he majored in operations research. He has been active in the Society for American Baseball Research since 1983 and has published several articles on baseball.

Sources

Baseball-reference.com.

Mednick, Barry, and Herman Krabbenhoft. “Twenty Game Losers –1961-1987,” Baseball Quarterly Reviews, Volume 2, Number 4 (1987).

Mednick, Barry. Research presentation “Twenty Game Losers,” 1987 SABR national convention, Washington, D.C.

Neft, David S., & Richard M. Cohen. The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball, 6th edition (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987).

Petriello, Mike. “Archer restores value with strong second half,” mlb.com, November 10, 2016. m.mlb.com/news/article/208476454/chris-archer-restores-value-in-second-half/.