The Day Ted Williams Became the Last .400 Hitter in Baseball

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

September 28, 1941. Shibe Park, Philadelphia. The Red Sox split a Sunday doubleheader with Connie Mack’s Athletics on the final day of the 1941 season. These were meaningless games in the standings; the Red Sox were in second place but 17 1/2 games behind the Yankees and the Athletics were dead last, 37 1/2 games out of first. But these were professionals and there was something else at stake.

September 28, 1941. Shibe Park, Philadelphia. The Red Sox split a Sunday doubleheader with Connie Mack’s Athletics on the final day of the 1941 season. These were meaningless games in the standings; the Red Sox were in second place but 17 1/2 games behind the Yankees and the Athletics were dead last, 37 1/2 games out of first. But these were professionals and there was something else at stake.

Young Ted Williams, who had turned 23 less than a month earlier, woke up that morning hitting .39955 on the year, just .00045 below the hallowed .400 mark. Except for a stretch from July 11–24, when his batting average dipped as low as .393, he’d been hitting above .400 since May 25.

After closing out Boston’s final home game at Fenway Park on September 21, Williams was batting .4055. There were six games left in the season; three in Washington and three in Philadelphia. Ted was 1-for-3 on the 23rd, and then in a doubleheader on the 24th, he was 0-for-3 and 1-for-4. He’d gone 2-for-10 and seen his average plunge to a perilous .4009. The weather was turning colder–not good for Williams. There was a lot on the line, and the team had two days off, the 25th and 26th. On the morning of September 27, the Philadelphia Bulletin headline noted what Williams faced: “Williams Risks Batting Mark” with a subhead showing his determination to play out the full season: “Boston Star Refuses to Protect his Season’s Record of .401.” This is when Ted could have sat out the final three games.

There’s a longstanding legend that Sox manager Joe Cronin had gone to Ted on Saturday evening and told him he could sit out the game to preserve his average, and nobody would have blamed him. If this had occurred, it would have been Friday night, before the Saturday game. Indeed, the Bulletin reported, “There was a rumor that Manager Joe Cronin would let Ted spend the rest of the year on the bench to protect his batting mark.” Williams took “a special session of batting practice at Shibe Park” during the day on Friday, after the Red Sox arrived in town, and Ted told the Bulletin’s Frank Yeutter, “I either make it or I don’t.”

Yeutter mentioned to readers a couple of obstacles Williams would face: “the lengthening shadows of autumn afternoons, and facing strange young pitchers getting the usual end-of-the-season tryouts.” The advantage, he said, was in the pitcher’s favor.

On Saturday the Athletics rookie pitcher Roger Wolff was pitching in only his second-ever major league game (he had lost a tight 1–0 game in Washington the previous Saturday, allowing just three hits). Williams drew a walk from Wolff his first time up and then doubled to right field. But then he flied out to Eddie Collins Jr. in right, fouled out to first baseman Bob Johnson, and struck out—the only man Wolff whiffed. It was Ted’s last strikeout of the season, number 27.

By batting 1-for-4, Ted’s batting average dropped to .39955. It could have been rounded up to .400 if he had sat out the two Sunday games. But .39955 was not .400.

Naturally, Williams wanted to hit .400. He had no way to know that he’d be the last .400 hitter in the twentieth century, but a .400 batting average in 1941 was still a major mark of distinction. Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby had each hit .400 three times. Hornsby could have done it a fourth time, if one applied rounding. Entering the last game of the 1921 season, he was hitting .39966. Hornsby played that game, failed to get a hit in four at-bats, and saw his final average fall to .397.

Ted said that his own teammate Jimmie Foxx had once lost a batting title to Buddy Myer by sitting out the last day of the season in 1935. It was not true, but Williams and biographer John Underwood apparently believed it was. Foxx finished third, batting .346 to Joe Vosmik’s .348 and Myer’s .349. In fact, Foxx did bat and was 3-for-4 on the final day. Myer had a 4-for-5 day.

In his autobiography, My Turn At Bat, Williams recalls Joe Cronin telling him, “You don’t have to be put in if you don’t want to. You’re officially .400.”1 Ted reports his reaction: “Well, God, that hit me like a goddamn lightning bolt! What do you mean I don’t have to play today?”2

At some point, the subject had been raised. The September 29 Christian Science Monitor reported, “A week ago it was suggested to the young outfielder that he might stay out of the game for the remainder of the season and thus assure his finishing in the select circle. But he chose rather to play the season out in his regular position, even though it jeopardized his standing.”3

The Sporting News said Ted had declared, “I want to have more than my toenails on the line.”

Williams didn’t want to hit .400 by the rounding of a number, and truth be told, .39955 is not .400—as he would have been reminded by newspaper headlines he may have seen that Sunday morning. Williams was an inveterate newspaper reader, typically reading four or five a day. If he saw The New York Times, he would have seen WILLIAMS AT .3996 AS RED SOX WIN, 5–1; STAR BATTER SLIPS BELOW .400 GOAL. Had he seen the Washington Post, he would have read its headline: WILLIAMS DROPS BELOW .400 AS RED SOX DEFEAT A’S, 5–1. Whether the Chicago Tribune made it to Philadelphia before game time, we don’t know; the Tribune headline read WILLIAMS DROPS UNDER .400. The Boston Globe’s game story headline? WILLIAMS GETS ONLY ONE HIT, with a subhead reading “Average Now is .399 as Red Sox Win, 5–1.”

And Sunday morning’s Philadelphia Inquirer was unambiguous: “SOX TOP A’s; WILLIAMS FALLS TO .399.”

Ted really didn’t have a choice. He had to hit. Perhaps it took a little less personal courage, but his actual accomplishment was no less dramatic. Everyone knew what was on the line. He’d be facing Dick Fowler in the first game–a rookie like Wolff, pitching in only his fourth big-league game. Mr. Mack reportedly told the Athletics to play it straight, as Porter Vaughan—the second pitcher to face Williams in the first game—explained: “Connie Mack didn’t talk to the pitchers but he talked to the catcher, Frank Hayes. Frank was a good catcher. When Ted came to bat, he told Ted that the pitchers had the word from Mr. Mack that they didn’t ought to let up at all on Ted, and if they did, they’d have to pay the consequences.”4

Joe Cronin had told the Boston Globe before the game: “If there’s ever a ballplayer who deserved to hit .400, it’s Ted. He’s given up plenty of chances to bunt and protect his average in recent weeks. He wouldn’t think of getting out of the lineup to keep his average intact. Moreover, most of the other stars who have bettered the mark before were helped by no foul strike rules or sacrifice fly regulations.”5 Indeed, had the rule been in effect which does not count a sacrifice fly as an at-bat, Ted would have entered the day hitting comfortably above .400, at .40498. But in 1941, a sacrifice fly—Ted had six of them—was counted as an at-bat and an out.

Ted himself kept it simple: “‘Gee, I only hope I can hit .400,’ was all he would say.”6

The Philadelphia Bulletin’s Yeutter reported that “Before the two games started he was nervous and sat on the bench, biting his fingernails. His mammoth hands trembled. He condemned himself for getting only one hit for four times at bat Saturday. He wondered who was going to pitch for the Athletics. He asked Jimmie Foxx if the late afternoon autumn shadows ever bothered him when he was a kingpin hitting in Shibe Park. He asked if the Athletics had knuckleball pitchers, for knucklers had been his nemesis all year.” Wolff, who had struck out Ted his last time up the day before, was a knuckleballer.

After Saturday’s game, Ted was nervous. That evening, he said he walked the streets of Philadelphia for several hours with Red Sox clubhouse man Johnny Orlando, walking maybe ten miles talking about it.7 John Holway quotes Williams: “I went to bed early, but I just couldn’t sleep. I tossed and turned and finally went to sleep, still thinking about that .400 average.”8

Williams was batting cleanup, and Fowler retired the side in the first, so Ted led off the top of the second. “Bill McGowan was the plate umpire, and I’ll never forget it,” Ted recalled. “Just as I stepped in, he called time and slowly walked around the plate, bent over and began dusting it off. Without looking up, he said, ‘To hit .400 a batter has got to be loose. He has got to be loose.’”9

The first pitch was low and outside. The second was low and inside. On the 2–0 count, Ted was ready and he swung at Fowler’s next pitch. He “singled sharply to right” according to the Inquirer’s Stan Baumgartner. In My Turn At Bat, Williams called it “a liner between first and second.” Gerry Moore of the Boston Globe called it “a sizzling single past first baseman Bob Johnson’s right.”

After that first hit, Ted’s average stood at .40089. If he’d made an out his second time up, he’d be hitting exactly .400. He had nothing to lose by taking that second at-bat. If he’d made an out, would he have allowed himself to be taken out of the game? We can’t know. But the question became moot when he led off the fifth inning, still facing Fowler, and homered on a 1–0 pitch, driving the ball over the high right-center field wall, a shot of perhaps 440 feet. It was his 37th homer of the year; he led both leagues in homers. Now he was batting .40222 and could make outs each of the next two times up and still be hitting a little over .400 at .40044.

But he didn’t. The Red Sox had taken a 3–2 lead in the top of the fifth, but the A’s scored nine times in the bottom of the inning, building up an 11–3 lead. Next time up, in the top of the seventh, Ted was facing reliever Porter Vaughan, who threw two straight curve balls, both of which missed the plate. Vaughn threw another curve, and Ted guessed correctly. He was waiting for it. “I hit a bullet right through the middle–base hit.”10 It was a single, and the Red Sox scored six runs that inning, closing the gap to 11–10 (they’d scored once in the sixth, too), and he singled off Vaughan a second time.

Vaughan told the story:

He got two clean singles off me. On the first one, he hit off a curve ball. Our second baseman was Crash Davis. Crash and I had come up at the same time. He played Ted in the hole between second and first. Ted hit the ball to the right of the second baseman. The second one he hit was a fast ball. I threw him a fastball. Bob Johnson, who was a leftfielder, was playing first base. Dick Siebert, our regular first baseman, had gone back to Minnesota; he taught out there. Johnson didn’t get to the ball; it was between him and the base. It was close to first base. Ted hit it right down the line. Obviously I didn’t fool him at all. He had wonderful eyesight and very quick hands. It was almost impossible to fool him. He really studied pitchers and remembered everything they threw him.11

Williams was 4-for-5 in the first game with two RBIs and two runs scored. He might even have been 5-for-5 but for the official scorer. In his final at-bat against Newman Shirley, yet another rookie (the hardest pitchers for Ted to hit, since they were neither predictable nor necessarily accurate), he grounded to second base and reached base, but with an error charged to second baseman Crash Davis. The Associated Press said that “a very ponderous” scoring decision “robbed” Ted of his fifth consecutive hit, though in his book, The Last .400 Hitter, John Holway noted that none of the other writers argued the decision.12

And even though Boston scored twice in the top of the ninth and won the game, 12–11, the Philly fans were all for Ted all day long. “Each time he came to bat the crowd roared, and when he went back to left field each inning the bleacherites gave him added applause,” wrote the Evening Bulletin.

By the end of the first game, Williams was batting .40397. He could have gone 0-for-4 in the second game and still been above .400 at .40044.

But he wasn’t done. In the second game, he faced Fred Caligiuri, who remembered Mack telling him to bear down: “Don’t give him anything! Pitch to him!” Caligiuri talked about pitching to Ted. “He could hit most fast balls, and the only way to get him out is to change speeds on him. We tried to change up on him, if I remember. I know one changeup I threw him he hit—in Shibe Park there was a kind of a megaphone that sits up on top of the wall, and that ball went on a line right into that megaphone and fell back into the park for a double. I suppose that megaphone was at least maybe two feet across, just a speaker up there. He hit it pretty good. It kept it in the ballpark. If it had been a few feet left or right, it would have gone out of the ballpark.”13 Indeed, only the ground rules kept the ball from being a homer, since the loudspeaker was deemed in fair territory. That ground-rule double was Ted’s second hit of the second game; he’d singled between first and second his first time up.

Finally, in his eighth time to the plate that day, with darkness encroaching, the Athletics got Ted Williams out, when he flied out to right field. He was officially 6-for-8, hitting .40570, or, when rounded up: .406.

“There was not a questionable hit among the group,” wrote the Inquirer. “All were slashing drives that whistled through the infield or fell far out of reach of the outfielders.”

After the game, Ted said he’d never felt nervous in baseball before. Now, he said, “I was shaking like a leaf when I went to bat the first time. Then when I got that first hit, I was all set. I felt good. Gee, there’s a lot of luck making that many hits.” He turned to Jimmie Foxx and exclaimed, “Just think–hitting .400. What do you think of that, Slug? Just a kid like me hitting that high.”

The September 29 Philadelphia Evening Bulletin wound up its story:

Although the second game was called in the eighth inning by Umpire John Quinn on account of darkness, at least 2,000 persons waited around the Boston dressing room and on 21st Street, to see Williams leave. He was surrounded by a mob that pinned him against the wall and made him autograph every conceivable kind of paper, book or scorecard. A couple of cops rescued him so he could make a train from North Philadelphia. But he enjoyed the ordeal and left only when he was shoved in a taxicab.

By virtue of reaching base six of the eight times up (not counting reaching on the error), Ted Williams had achieved a season on-base percentage of .553. More than half the times he came to bat in 1941, he got on base, and he struck out only 27 times all season.

In 2012 Miguel Cabrera of the Detroit Tigers won the Triple Crown for the first time since Carl Yastrzemski did it for the Boston Red Sox in 1967. Will someone hit .400 again? That’s the gist for another story, but a good place to start would be pages 77–132 in Stephen Jay Gould’s Full House: The Spread of Excellence from Plato to Darwin (New York: Harmony Books, 1996), an expansion of his essay “Entropic homogeneity isn’t why no one hits .400 any more,” which appeared in the August 1986 issue of Discover.

BILL NOWLIN has written or edited four books on Ted Williams, and has another one on the drawing board. As a 12-year-old, he was inspired by Williams’s 1957 season, when Ted hit .388 — in the year he turned 39. Bill has been vice president of SABR since 2004.

Related links:

- Read about Game 1 of the Red Sox-A’s doubleheader on September 28, 1941 at the SABR Games Project

- Read about Game 2 of the Red Sox-A’s doubleheader on September 28, 1941 at the SABR Games Project

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rock Hoffman for providing photocopies of the Philadelphia newspapers of the day.

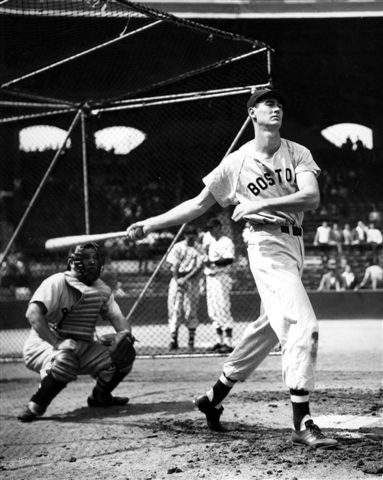

Photo credit: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 Ted Williams with David Pietrusza, My Life in Pictures (Kingston NY: Total Sports Illustrated, 2001), 43.

2 My Life in Pictures, 43.

3 Christian Science Monitor, September 29, 1941.

4 Porter Vaughan interview with author, July 30, 1997. Williams says Hayes told him, “Ted, Mr. Mack told us if we let up on you he’ll run us out of baseball, I wish you all the luck in the world, but we’re not giving you a damn thing.” Ted Williams, My Turn At Bat (New York: Fireside Books, 1969), 90.

5 Boston Globe, September 29, 1941.

6 Boston Globe, September 29, 1941.

7 My Turn At Bat, 87.

8 John Holway, The Last .400 Hitter (Dubuque: William C. Brown, 1992), 282.

9 My Turn At Bat, 90.

10 Holway, 285.

11 Porter Vaughan interview with author, July 30, 1997.

12 Holway, 287.

13 Fred Caligiuri interview with author, July 7, 1997.